A Residue of Anomalies

Review of Think to New Worlds: The Cultural History of Charles Fort and His Followers by Joshua Blu Buhs (University of Chicago Press, July 2024)

Note: This review essay of Joshua Blu Buhs’s Think to New Worlds: The Cultural History of Charles Fort and His Followers was originally published on July 8, 2024 in the journal Nature (631, 269-270), under the title/subtitle of: “How conspiracies took root in our culture: UFO hunters and anti-vaxxers might seem like modern phenomena, but they both take inspiration from a little-known anti-science movement.” What follows is a slightly longer version of my review, with my original title and subtitle. —Michael Shermer

In March 2024, a mammoth review by the US Department of Defense concluded that there was “no evidence” that the US government had encountered alien life. Yet, that pronouncement is unlikely to have changed many minds. Popular belief in extraterrestrial visitors — fueled by sightings of unidentified flying objects (UFOs) — is strong. Even the defense department’s report, in a resigned tone, admits that the litany of television shows, books, films and Internet content on the topic has “reinforced these beliefs.”

UFOs, a cultural phenomenon since the 1940s, have experienced a resurgence in the conspiracy-laced zeitgeist of the early twenty-first century. They were discussed in a series of hearings held in the US Congress last year. Each episode of the television series Ancient Aliens on US-based channel History features alleged anomalies that scientists purportedly cannot explain without invoking extraterrestrials.

These pseudoscientific yet wildly popular “explanations” of mysterious phenomena take inspiration — often unknowingly — from the life and work of a man who achieved notoriety during the early decades of the previous century: Charles Fort (1874–1932). His penchant for compiling earnest reports of bizarre happenings by scanning through newspapers, magazines and scientific journals set off an army of emulators — the Forteans, as cultural historian and author Joshua Blu Buhs (see also his previous book, Bigfoot: The Life and Times of a Legend), skillfully recounts in Think to New Worlds: The Cultural History of Charles Fort and His Followers, a compelling narrative about the birth of modern “anomaly hunting.”

The “residue problem” in science means that no matter how all-encompassing a theory is there will always be a residue of anomalies for which it cannot account. The most famous case in the history of science is that Newton’s gravitational theory could not account for the precession of the planet Mercury’s orbit, subsequently explained by Einstein’s theory of relativity. Many paradigm shifts happen, in fact, when enough anomalies build up to justify a new explanatory model.

Unfortunately, residues of unexplained anomalies open the door to autodidacts to jump in with their alternative theories to mainstream science. The widely-viewed 2023 Netflix series Ancient Apocalypse, for example, follows alternative archaeologist Graham Hancock around the world as he exposes anomalies he asserts are unexplained by science and best accounted for by the lost civilization of Atlantis. As noted, every episode of the popular History Channel series Ancient Aliens features alleged anomalies that scientists purportedly cannot explain without invoking extraterrestrials, and what were those UAP videos screened in the halls of Congress last year but Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena?

This tradition of collecting anomalies and cataloging them into paranormal, supernatural, extraterrestrial, mystical, and magical worlds just beyond the horizons of science can be traced back to Fort and his Fortean followers, which in turn shaped science fiction, avant-garde modernism, Surrealist art, and UFOlogy throughout the 20th century,.

Fort’s research methodology—more fully developed and proselytized by the writer and adman Tiffany Thayer, who went on to found the Fortean Society—is what today is called “anomaly hunting.” Intrepid would-be researchers rummage through scientific books, journal articles, magazine features, and newspaper stories for anything that doesn’t quite seem to fit with mainstream science. Fort’s original anomaly hunting expeditions netted him a plethora of weird things for which scientists had no explanation: frogs and fishes falling from the sky, ball lightning, UFOs, cryptids (like Bigfoot), talking dogs and vampires, poltergeist events, spontaneous human combustion, levitation, unexplained disappearances, out-of-place artifacts, and highly unusual coincidences.

Fort and his followers — Forteans, as they called themselves — “had their largest effect on the practices of science fiction, aesthetic modernism, and UFOlogy, pursuits seemingly peripheral to the mainstream,” Buhs explains in embedding his subject in time and place, and contrasting the movement he traces with that of the world of early 20th-century science. Buhs’ thesis — well supported and cogently argued — is that the belief in “modernity” as a coldly secular and mechanically scientific worldview devoid of wonder is wrong. On the contrary, “modernity released the marvelous, expanded the possible ways in which humanity came into the presence of the awesome. The death of God and the rise of science as the preeminent process for creating truth opened new provinces, provided new materials for imagining, inventing, experiencing enchantment.” The anomalies compiled by Fort and Forteans served as “inspiration for those who tried to imagine the future,” one that they could create “rather than having it thrust upon the world.”

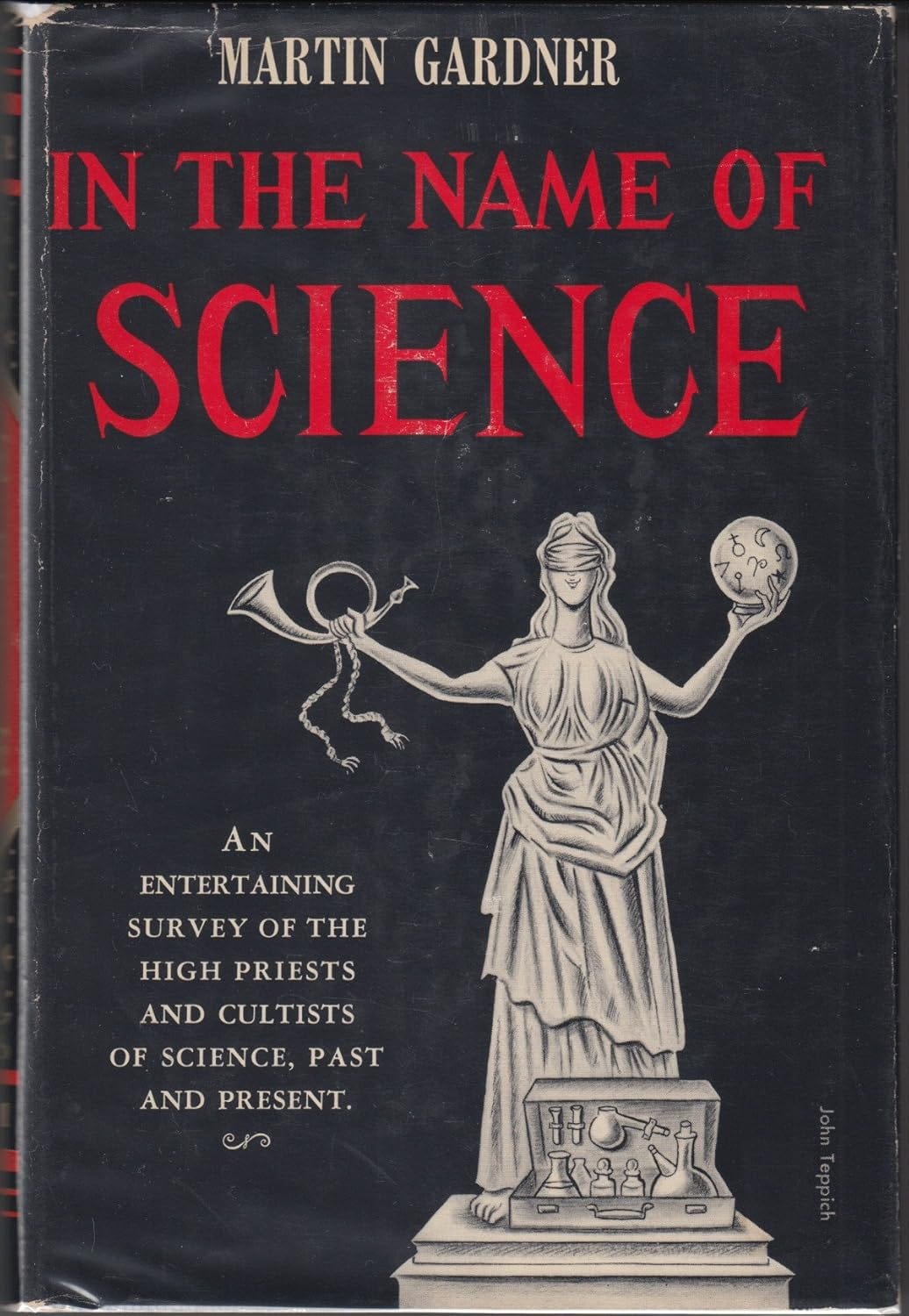

Not everyone was so influenced by Fort and Foreanism. In 1950, the science writer Martin Gardner published an article in the Antioch Review entitled “The Hermit Scientist,” about what we would today call pseudoscientists, and in 1952 he expanded it into a book titled In the Name of Science with the descriptive subtitle “An entertaining survey of the high priests and cultists of science, past and present” (later republished as Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science and now considered a classic in modern skepticism). Said cultists were none other than Forteans and their ideological offspring, about whom Gardner upbraided as cranks, which he characterized thusly: “(1) He considers himself a genius. (2) He regards his colleagues, without exception, as ignorant blockheads. (3) He believes himself unjustly persecuted and discriminated against. (4) He has strong compulsions to focus his attacks on the greatest scientists and the best-established theories. (5) He often has a tendency to write in a complex jargon, in many cases making use of terms and phrases he himself has coined.”

This mid-century encounter established a tension between believers (represented by Fort and Forteans of all stripes) and skeptics (represented by Gardner and others worried not only about Fortean claims but additional paranormal and occult beliefs). “If the present trend continues,” Gardner concluded, “we can expect a wide variety of these men, with theories yet unimaginable, to put in their appearance in the years immediately ahead. They will write impressive books, give inspiring lectures, organize exciting cults. They may achieve a following of one—or one million. In any case, it will be well for ourselves and for society if we are on our guard against them.”

Nevertheless, as Buhs notes, Garnder was a “mysterian”—those who believe there are some mysteries that will never be explained by science, such as consciousness, free will, and God—unwilling to completely dismiss all Fortean claims outright. And this opened the door to a different form of skepticism. Of Fort, Buhs reveals, “His was a radical skepticism that refused to accept anything as absolutely true or absolutely false.”

The problem with such enchanted thinking in which there is no clear boundary between science and pseudoscience, between the natural and the supernatural, between truth and falsehood, is today’s collapse in confidence in our institutions, from science and medicine to politics and the media. “Fort and Forteans played their part in the creation of this world,” Buhs concludes his cultural history. “They eroded the distinctions between truth and falsity, undermined the authority of experts and expertise. They launched a thousand conspiracies into the national consciousness.” Fort’s playful anomaly hunting “had been replaced by Thayer’s acerbic nihilism, which became omnipresent and decoupled from any need to compile evidence or craft arguments.” As a result, a century after Fort’s swerve away from the scientism of the modern world, we have theories that consist of only two words, “Fake News!”, one word, “Rigged!” and even one letter, “Q”.

In the end, science needs outsiders and mavericks who poke and prod and push accepted theories until they either collapse or are reinforced even stronger. But it also needs standards of evidence and norms of objectivity, truth telling, accountability, and professionalism. Unfortunately, outsiders like Forteans and their modern descendants tend to fall far short of these standards and norms.

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine and author of Why People Believe Weird Things, Heavens on Earth, and Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational. His next book is Truth: What it is, How to Find it, Why it Matters, to be publisher Fall, 2025.