Are We All Nazis?

If we are all inherently racist, as many people today believe, are we also all Nazis? Some thoughts on evil and human nature

In two recent Skeptic columns I have discussed the Holocaust in the context of International Holocaust Remembrance Day (celebrating the liberation of Auschwitz on January 27, 1945) and in response to Whoopi Goldberg’s televised gaff about the Holocaust not being a race-based genocide (because in today’s parlance race can only be about skin color), whereas in fact the Nazis considered Jews an inferior (and nefarious) race that must be exterminated. In this context, today’s broader conversation driven by the belief that we are all racists brings to mind my title question: Are we all Nazis?

Nuremberg Rally 1933 Adolf Hitler (L) and Ernst Roehm (R) commemorating those who fell for the (Nazi) movement during a mass rally of the SS and SA (Photo by ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

I have devoted much of my career to understanding how a nation of educated, enlightened, and cultured people like Germany of the 1930s could be brainwashed into becoming goose-stepping Nazis in a matter of a few years. I have written articles and books on the matter,1 and in 2010, I even worked with Dateline NBC on a two-hour special in which we replicated a number of now classic psychology experiments in human gullibility and social susceptibility. In one experiment, for example, an unsuspecting subject and a room full of confederates (i.e., actors who know the objective of the study) were asked to fill out applications to participate in a television game show. The confederates dutifully filled out their forms, even as the room gradually filled with (theater) smoke, right along with our unsuspecting subjects who had every reason to believe that the building was actually on fire. As the subjects coughed and waved the smoke away, heads bent to their trivial task, the herd instinct became ever more blazingly obvious. But was it? Do we not normally get our cues for how to act from others? Is there not a certain logic to following one’s group mates when, in normal circumstances, if there really was a fire they really would respond to it accordingly? More on this later.

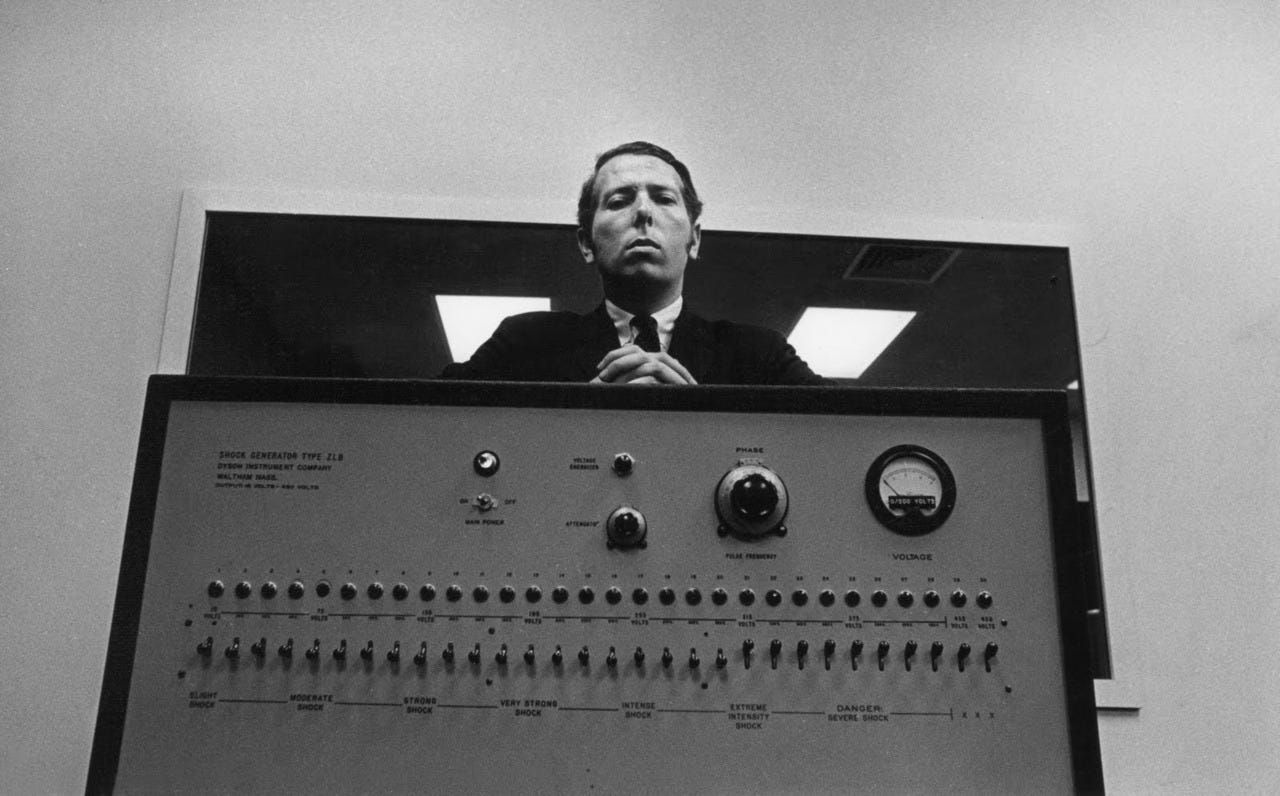

The most dramatic experiment we replicated was Yale University professor Stanley Milgram’s famous shock experiments from the early 1960s on the nature of evil. (You can watch both parts here and here.) In a New York City studio, we tested six subjects who believed that they were auditioning for a new reality show called “What a Pain!”

A contestant (left) for our faux television reality show “What a Pain!” talks to our actors playing the learner (middle) and the authority (right) to be obeyed.

We followed Milgram’s protocols and had our subjects read a list of paired words to a “learner” (an actor named Tyler), then present the first word of each pair again. When Tyler gave a prearranged incorrect answer, our subjects were instructed by an authority figure (an actor named Jeremy) to deliver an electric shock modeled after Milgram’s contraption, a shock box with toggle switches in 15-volt increments that ranged from 15 volts all to 450 volts, and featured such labels as Slight Shock, Moderate Shock, Strong Shock, Very Strong Shock, Intense Shock, Extreme Intensity Shock, and DANGER: Severe Shock, XXXX.2 Despite the predictions of 40 psychiatrists that Milgram surveyed before the experiment, who estimated that only one percent of subjects would go all the way to the end, 65 percent of them completed the experiment, flipping that final toggle switch to deliver a shocking 450 volts.

Who was most likely to go the distance in maximal shock delivery? Surprisingly—and counter-intuitively—gender, age, occupation, and personality characteristics mattered little to the outcome. Similar levels of punishment were delivered by the young and the old, by males and females, and by blue-collar and white-collar workers alike. What mattered most was physical proximity and group pressure. The closer the learner was to the teacher, the less of a shock the latter delivered. And when Milgram added more confederates to encourage the teacher to administer ever more powerful shocks, most teachers complied; but when the confederate themselves rebelled against the authority figure’s instructions, the teacher was equally disinclined to obey. Nevertheless, 100 percent of Milgram’s subjects delivered at least a “strong shock” of 135 volts.3

Milgram characterized his experiments as testing “obedience to authority,” and most interpretations over the decades have focused on subjects’ unquestioning adherence to an authority’s commands. What I saw in our replication study, however, was great reluctance and disquietude in all of our subjects nearly every step of the way. Our first subject, Emily, quit the moment she was told the protocol. “This isn’t really my thing,” she said with nervous laughter. When our second subject, Julie, got to 75 volts (having flipped five switches) she heard Tyler groan. “I don’t think I want to keep doing this,” she said.

Jeremy pressed the case: “Please continue.”

“No, I’m sorry,” Julie protested. “I don’t think I want to.”

“It’s absolutely imperative that you continue,” Jeremy insisted.

“It’s imperative that I continue?” Julie replied in defiance. “I think that—I’m like, I’m okay with it. I think I’m good.”

“You really have no other choice,” Jeremy said in a firm voice. “I need you to continue until the end of the test.”

Julie stood her ground: “No. I’m sorry. I can just see where this is going, and I just—I don’t—I think I’m good. I think I’m good to go. I think I’m going to leave now.”

At that point the show’s host Chris Hansen entered the room to debrief her and introduce her to Tyler, and then Chris asked Julie what was going through her mind. “I didn’t want to hurt Tyler,” she said. “And then I just wanted to get out. And I’m mad that I let it even go five [toggle switches]. I’m sorry, Tyler.”

Our contestant/subject Julie refuses to continue shocking the learner once he begins to cry out in pain.

Our third subject, Lateefah, started off enthusiastically enough, but as she made her way up the row of toggle switches, her facial expressions and body language made it clear that she was uncomfortable; she squirmed, gritted her teeth, and shook her fists with each toggled shock. At 120 volts she turned to look at Jeremy, seemingly seeking an out. “Please continue,” he authoritatively instructed. At 165 volts, when Tyler screamed “Ah! Ah! Get me out of here! I refuse to go on! Let me out!” Lateefah pleaded with Jeremy. “Oh my gosh. I’m getting all…like…I can’t…”; nevertheless Jeremy pushed her politely, but firmly, to continue. At 180 volts, with Tyler screaming in agony, Lateefah couldn’t take it anymore. She turned to Jeremy: “I know I’m not the one feeling the pain, but I hear him screaming and asking to get out, and it’s almost like my instinct and gut is like, ‘Stop,’ because you’re hurting somebody and you don’t even know why you’re hurting them outside of the fact that it’s for a TV show.” Jeremy icily commanded her to “please continue.” As Lateefah reluctantly turned to the shock box, she silently mouthed, “Oh my God.”

At this point, as in Milgram’s experiment, we instructed Tyler to go silent. As Lateefah moved into the 300-volt range it was obvious that she was greatly distressed, so Chris stepped in to stop the experiment, asking her if she was getting upset. “Yeah, my heart’s beating really fast.” Hansen then asked, “What was it about Jeremy that convinced you that you should keep going here?” Lateefah gave us this glance into moral reasoning about the power of authority: “I didn’t know what was going to happen to me if I stopped. He just—he had no emotion. I was afraid of him.”

Our contestant/subject Lateefah flips the switches of electric shock even though she was reluctant to do so for most of the experiment.

Our fourth subject, a man named Aranit, unflinchingly cruised through the first set of toggle switches, pausing at 180 volts to apologize to Tyler after his audible protests of pain: “I’m going to hurt you and I’m really sorry.” After a few more rungs up the shock ladder, accompanied by more agonizing pleas by Tyler to stop the proceedings, Aranit encouraged him, saying, “Come on. You can do this. We are almost through.” Later, the punishments were peppered with positive affirmations. “Good.” “Okay.” After completing the experiment Chris asked, “Did it bother you to shock him?” Aranit admitted, “Oh, yeah, it did. Actually, it did. And especially when he wasn’t answering anymore.”

Our contestant/subject Aranit (left) continues shocking the learner upon the encouragement of our “authority” figure Jeremy (right).

Two other subjects in our replication, a man and a woman, went all the way to 450 volts, giving us a final tally of five out of six who administered shocks, and three who went all the way to the end of maximal electrical evil. All of the subjects were debriefed and assured that no shocks had actually been delivered, and after lots of laughs and hugs and apologies, everyone departed none the worse for wear.4

What are we to make of these results? In the 1960s heyday of the Blank Slate model of human nature,5 it was taken to mean that human behavior is almost infinitely malleable, and Milgram’s data seemed to confirm the idea that degenerate acts are primarily the result of degenerate environments (Nazi Germany being, perhaps, the ultimate example). In other words, there are no bad apples, just bad barrels.

Milgram’s interpretation of his data included what he called the “agentic state,” which is “the condition a person is in when he sees himself as an agent for carrying out another person’s wishes and they therefore no longer see themselves as responsible for their actions. Once this critical shift of viewpoint has occurred in the person, all of the essential features of obedience follow.” Subjects who are told that they are playing a role in an experiment are stuck in a no-man’s land somewhere between authority figure, in the form of a white lab-coated scientist, and stooge, in the form of a defenseless learner in another room. They undergo a mental shift from being moral agents in themselves who make their own decisions (that autonomous state) to the ambiguous and susceptible state of being an intermediary in a hierarchy and therefore prone to unqualified obedience (the agentic state).

Milgram believed that almost anyone put into this agentic state could be pulled into evil one step at a time—in this case 15 volts at a time—until they were so far down the path there was no turning back. “What is surprising is how far ordinary individuals will go in complying with the experimenter’s instructions,” Milgram recalled. “It is psychologically easy to ignore responsibility when one is only an intermediate link in a chain of evil action but is far from the final consequences of the action.” This combination of a step-wise path, plus a self-assured authority figure that keeps the pressure on at every step, is the double whammy that makes evil of this nature so insidious.

Put yourself into the mind of one of these subjects—either in Milgram’s experiment or in our NBC replication. It’s an experiment conducted at the prestigious Yale University—or at NBC studios. It’s being supervised by an established institution—a national university or a national network. It’s for science—or it’s for television. It’s being run by a white-lab-coated scientist—or by a casting director. The authorities overseeing the experiment are either university professors or network executives. An agent—someone carrying out someone else’s wishes under such conditions—would feel in no position to object. And why should she? It’s for a good cause, after all—the advancement of science, or the development of a new and interesting television series. Out of context, if you ask people—even experts, as Milgram did—how many people would go all the way to 450 volts, they lowball the estimate by a considerable degree, as Milgram’s psychiatrists did. As Milgram later reflected: “I am forever astonished that when lecturing on the obedience experiments in colleges across the country, I faced young men who were aghast at the behavior of experimental subjects and proclaimed they would never behave in such a way, but who, in a matter of months, were brought into the military and performed without compunction actions that made shocking the victim seem pallid.”6

In the sociobiological and evolutionary psychology revolutions of the 1980s and 1990s, the interpretation of Milgram’s results shifted toward the nature/biological end of the spectrum from its previous emphasis on nurture/environment. The interpretation softened somewhat as the multidimensional nature of human behavior was taken into account. As it is with most human action, moral behavior is incredibly complex and includes an array of causal factors, obedience to authority being just one among many. The shock experiments didn’t actually reveal just how primed all of us are to inflict violence for the flimsiest of excuses; that is, it isn’t a simple case of bad apples looking for a bad barrel in order to cut loose. Rather the experiments demonstrate that all of us have conflicting moral tendencies that lie deep within.

Our moral nature includes a propensity to be sympathetic, kind, and good to our fellow kith and kin and friends, as well as an inclination to be xenophobic, cruel, and evil to tribal Others. And the dials for all of these can be adjusted up and down depending on a wide range of conditions and circumstances, perceptions and states of mind, all interacting in a complex suite of variables that are difficult to tease apart. In point of fact, most of the 65 percent of Milgram’s subjects who went all the way to 450 volts did so with great anxiety, as did the subjects in our NBC replication. And it’s good to remember that 35 percent of Milgram’s subjects were exemplars of the disobedience to authority—they quit in defiance of what the authority figure told them to do.

Milgram’s model comes dangerously close to suggesting that subjects are really just puppets devoid of volition, which effectively lets Nazi bureaucrats off the hook as mere agentic automatons in an extermination engine run by the great paper-pushing administrator, Adolf Eichmann (whose actions as an unremarkable man in a morally bankrupt and conformist environment were famously described by Hannah Arendt as “the banality of evil.”). Eichmann had been one of the chief orchestrators of the Final Solution but, like his fellow Nazis at the Nuremberg trials, his defense was that he was innocent by virtue of the fact that he was only following orders. Befehl ist Befehl—orders are orders—is now known as the Nuremberg defense, and it’s an excuse that seems particularly feeble in a case like Eichmann’s. “My boss told me to kill millions of people so—hey—what could I do?”

The obvious problem with this model is that there can be no moral accountability if an individual is truly nothing more than a mindless zombie whose every action is controlled by some nefarious mastermind. Reading the transcript of Eichmann’s trial is mind numbing (it goes on for thousands of pages), as he both obfuscates his real role while shifting the blame entirely to his overseers, as in this statement:

What I said to myself was this: The Head of State has ordered it, and those exercising judicial authority over me are now transmitting it. I escaped into other areas and looked for a cover for myself which gave me some peace of mind at least, and so in this way I was able to shift—no, that is not the right term—to attach this whole thing one hundred percent to those in judicial authority who happened to be my superiors, to the head of State—since they gave the orders. So, deep down, I did not consider myself responsible and I felt free of guilt. I was greatly relieved that I had nothing to do with the actual physical extermination.7

The last statement might possibly be true—given how many battle-hardened SS Nazis were initially sickened at the site of a killing action—but the rest is pure spin-doctored malarkey and Arendt allowed herself to be taken in by it more than reason would allow, as the historian David Cesarani shows in his revealing biography Becoming Eichmann and as recounted in Margarethe von Trotta’s moving film Hanna Arendt.8 The evidence of Eichmann’s real role in the Holocaust was plain for all to see at the time, as dramatically re-enacted in Robert Young’s 2010 biopic entitled simply Eichmann, based on the transcripts of the interrogation of and confession by Eichmann just before his trail, conducted by the young Israeli police officer Avner Less, whose father was murdered in Auschwitz.9 Time and again, throughout hundreds of recorded hours, Less queries Eichmann about transports of Jews and gypsies sent to their death, all followed by denials and lapses of memory. Less then presses the point by showing Eichmann copies of transport documents with his signature at the bottom, leading Eichmann to say in an exasperated voice, “what’s your point?”

The point is that there is a mountain of evidence proving that Eichmann—like all the rest of the Nazi leadership—were not simply following orders. As Eichmann himself boasted when he wasn’t on trial: “When I reached the conclusion that it was necessary to do to the Jews what we did, I worked with the fanaticism a man can expect from himself. No doubt they considered me the right man in the right place…. I always acted 100 per cent, and in giving of order I certainly was not lukewarm.” As the genocide historian Daniel Jonah Goldhagen asks rhetorically, “Are these the words of a bureaucrat mindlessly, unreflectively doing his job about which he has no particular view?”10

The historian Yaacov Lozowick characterized the motives in his book Hitler’s Bureaucrats, in which he invokes a mountain-climbing metaphor: “Just as a man does not reach the peak of Mount Everest by accident, so Eichmann and his ilk did not come to murder Jews by accident or in a fit of absent-mindedness, nor by blindly obeying orders or by being small cogs in a big machine. They worked hard, thought hard, took the lead over many years. They were the alpinists of evil.”11

So it is clear enough that the Nazi leaders believed in their exterminationist ideology, but what about average German citizens? Were they all potential Nazis? And, by extension, are we all potential Nazis? I don’t think so. According to the historian of 20th century Germany and Hitler biographer Ian Kershaw, by the late 1930s—when it was too late to do anything about the Nazi regime—most Germans did not accept Nazi ideology, nor many of the planks in the regime’s platform, especially its militarist and exterminationist policies. We now know that most of Hitler’s military leaders did not want war in 1939 and warned their Führer that they were unprepared if other nations fought back ferociously. The euthanasia of the handicapped in the 1930s was resisted by most Germans and got so much bad press that the Nazis made the program secret and issued orders to never speak of it, a policy carried through the Final Solution and the Holocaust, which was shrouded in secrecy and mostly carried out in Poland, far from the prying eyes of German citizens. Hitler’s anti-communism appealed to right-leaning Germans but was rejected among industrial workers. By 1942, most citizens did not believe the declarations of victory issued by the propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, instead relying on secreted BBC reports of how the war was really going for Germany (not well). As the Nazi intelligence agency Sicherheitsdienst (SD) reported: “Our propaganda encounters rejection everywhere among the population because it is regarded as wrong and lying.”12

To return to where I began this analysis in asking “How could so many highly educated, intelligent, and cultured Germans become Nazis?” the answer is: “Most didn’t.” Certainly German citizens, satisfied with Hitler’s economic policies that pulled the country out of a severe depression, were uninterested in risking it all through foreign entanglements from which few would personally benefit. As Nazi Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring told psychiatrist Gustave Gilbert at the Nuremberg trials following the war:

Why, of course, the people don’t want war. Why would some poor slob on a farm want to risk his life in a war when the best that he can get out of it is to come back to his farm in one piece. Naturally, the common people don't want war; neither in Russia nor in England nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along…. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country.13

Even the anti-Semitism so famously on display in Hitler’s writings and speeches was only effective on Germans who were already anti-Semitic, as documented by Hugo Mercier in his 2020 book Not Born Yesterday.14 Mercier, in arguing overall that humans are not nearly as gullible as many people think, notes that a study on German anti-Semitism by Nico Voigtlander and Hans-Joachim Voth examined whether anti-Semitism was higher among Germans exposed to Nazi propaganda through radio, cinemas, rallies, and the like. “If mere repetition were effective, areas with greater exposure to propaganda should see the sharpest rise in anti-Semitism. In fact, the sheer exposure to propaganda had no effect at all. Instead, it was the presence of preexisting anti-Semitism that explained the regional variation in the effectiveness of propaganda. Only the areas that were the most anti-Semitic before Hitler came to power proved receptive. For people in these areas, the anti-Semitic propaganda might have been used as a reliable cue that the government was on their side, and thus that they could freely express their prejudices.”

The entire Nazi regime—not unlike the Soviet Union in the 20th century and North Korea in the 21st century—was held aloft on pluralistic ignorance, in which individual members of a group don’t believe something but believe that most others in the group believe it.15 When no one speaks up—or are prevented from speaking up through state-sponsored censorship or imprisonment—it produces a “spiral of silence” that can transmogrify into witch hunts, purges, pogroms, and repressive political regimes. This is why totalitarian and theocratic regimes restrict speech, press, protest, trade, and travel, and why the route to breaking the bonds of such repressive governments and ideologies is free speech, free press, free protest, free trade, and accurate and trustworthy information.

See, for example: Shermer, Michael. 2015. The Moral Arc. New York: Henry Holt.

Milgram, Stanley. 1969. Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View. New York: Harper.

Ibid.

In screening this segment of the NBC special in public talks I am occasionally asked how we got this replication passed by an Institutional Review Board (an IRB), which is required for scientific research. We didn’t. This was for network television, not an academic laboratory, so the equivalent of an IRB was review by NBC’s legal department, which approved it. This seems to surprise—even shock—many academics, until I remind them of what people do to one another on reality television programs in which subjects are stranded on a remote island and left to fend for themselves in various contrivances that resemble a Hobbesian world of a war of all against all.

Pinker, Steven. 2002. The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. New York: Viking.

Milgram, 1969.

The Trial of Adolf Eichmann, Session 95, July 13, 1961. https://bit.ly/3JkNNjy

Cesarani, David. 2006. Becoming Eichmann: Rethinking the Life, Crimes, and Trial of a “Desk Murderer”. New York: De Capo Press. Von Trotta, Margarethe (Director). 2012. Hannah Arendt. Zeitgeist Films. See also: Lipstadt, Deborah E. 2011. The Eichmann Trial. New York: Schocken.

Young, Robert. 2010. Eichmann. Regent Releasing, Here! Films. October.

Quoted in: Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah. 2009. Worse Than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity. New York: PublicAffairs, 158.

Lozowick, Yaacov. 2003. Hitler’s Bureaucrats: The Nazi Security Police and the Banality of Evil. New York: Continuum, 279.

Kershaw, Ian. 1983. “How Effective was Nazi Propaganda?” In D. Welch (Ed.), Nazi Propaganda: The Power and the Limitations (180-205). London: Croom Helm, 199.

Gustave Gilbert, "Interview with Herman Goering," Nuremberg Diary (New York: Da Capo, 1995; originally published New York: Farrar, Straus, 1947), 122, https://bit.ly/3x1ZINR/.

Mercier, Hugo. 2020. Not Born Yesterday: The Science of Who We Trust and What We Believe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

See, for example, Prentice, D. A. and D. T. Miller. 1993. “Pluralistic Ignorance and Alcohol Use on Campus: Some Consequences of Misperceiving the Social Norm.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. February, 64(2): 243-256. https://bit.ly/3txlN4E; Lambert, Tracy A., Arnold S. Kahn, and Kevin J. Apple. 2003. “Pluralistic Ignorance and Hooking Up.” The Journal of Sex Research. Vol. 40, No. 2, May, 129-133; Macy, Michael W., Robb Willer, and Ko Kuwabara. 2009. “The False Enforcement of Unpopular Norms.” American Journal of Sociology. Vol. 115, No. 2, September, 451-490.

“ To return to where I began this analysis in asking “How could so many highly educated, intelligent, and cultured Germans become Nazis?” the answer is: “Most didn’t.” ”

And yet the few Nazis managed to accomplish great evil.

The parallels to our own time are obvious:

(1) very few Americans (basically none?) wanted endless war in Afghanistan and Iraq.

(2) most Americans want a health-care-for-all system but even a pandemic that’s killed nearly a million of us couldn’t get our legislators to act.

Our governments do stuff regardless of what we want.

Thanks for the thorough and thoughtful article, Michael. In short, the understanding that I come away with is that many/most of us are probably not potential ideologues but most/many/enough of us are potential collaborators or aquiescers, in a society that prevents us from knowing the reservations of our peers to the noisiest voices in the culture or society. Whether those be governmental (WWII Germany, CCP, ...) or social (BLM, MAGA, AntiVax,...).

How does that sit with your intent?