Bending the Moral Arc

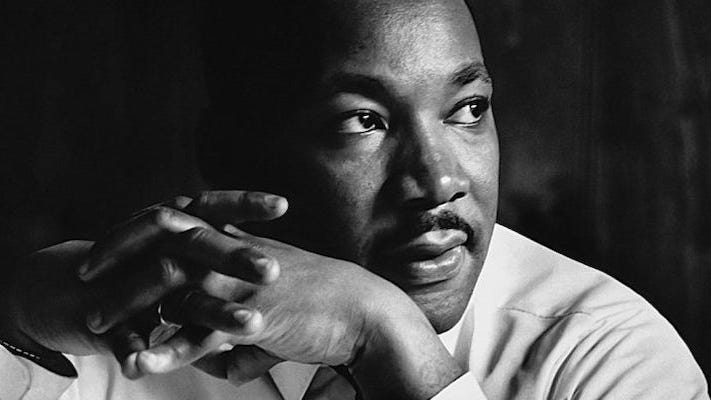

Honoring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. nearly 60 years after his "How Long" speech in Montgomery, Alabama on March 25, 1965

Sunday, March 21st, 1965. Selma, Alabama.

About 8,000 people gather at Brown Chapel and begin to march from the town of Selma to the city of Montgomery, Alabama. The demonstrators are predominantly African-American and they’re marching on the capitol for one reason. Justice. They want simply to be given the right to vote. But they’re not alone in their struggle. Demonstrators of “every race, religion, and class,” representing almost every state, have come to march with their black brothers and sisters.[1] And at the front of the march is the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Nobel Prize winner, preacher, and civil rights activist leading the march like Moses leading his people out of Egypt.

In the teeth of racial opposition backed by armed police and riot squads, they had tried to march twice before, but both times were met with violence by state troopers and a deputized posse. The first time—known as Bloody Sunday—the marchers were ordered to turn back but refused and, as onlookers cheered, they were met with tear gas, billy clubs, and rubber tubing wrapped in barbed wire. The second time they were again met by a line of state troopers and ordered to turn around, and after asking for permission to pray, King led them back.

But not this time. This time President Lyndon B. Johnson, finally having seen the writing on the wall, ordered that the marchers should be protected by 2,000 National Guard troops and federal marshals. And so they marched. For five days, over a span of 53 miles, through biting cold and frequent rain, they marched. Word spread, the number of demonstrators grew, and by the time they reached the steps of the capitol in Montgomery on March 25, their numbers had swelled to at least 25,000.

But King wasn’t allowed on the steps of the capitol—the marchers weren’t allowed on state property. Sitting in the capitol dome like Pontius Pilate, Alabama Governor George Wallace refused to come out and address the marchers, and Dr. King delivered his speech from a platform constructed on a flatbed truck parked on the street in front of the building.[2] And from that platform, King delivered his stirring anthem to freedom, first recalling how they had marched through “desolate valleys,” rested on “rocky byways,” were scorched by the sun, slept in mud, and were drenched by rains.

The crowd, consisting of freedom-seeking people who had assembled from around the United States listened intently as Dr. King implored them to remain committed to the nonviolent philosophy of civil disobedience, knowing that the patience of oppressed peoples wears thin and that our natural inclination is to hit back when struck. He asked, rhetorically, “How long will prejudice blind the visions of men, darken their understanding, and drive bright-eyed wisdom from her sacred throne?” And “How long will justice be crucified and truth bear it?” In response, Dr. King offered words of counsel, comfort, and assurance, saying that no matter the obstacles it wouldn’t be long before freedom was realized because, he said, quoting religious and biblical tropes, “truth crushed to earth will rise again,” “no lie can live forever,” “you shall reap what you sow,” and “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”[3]

It was one of the greatest speeches of Dr. King’s career, and arguably one of the greatest in the history of public oratory. And it worked. Less than five months later, on August 6th, 1965, President Johnson signed the voting rights act into law. It was just as Dr. King had said—the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice. The climatic end of the speech can be seen on YouTube:

Dr. King’s reference—the title inspiration for my 2015 book The Moral Arc—comes from the 19th-century abolitionist preacher Theodore Parker, who penned this piece of moral optimism in 1853, at a time when, if anything, pessimism would have been more appropriate as America was inexorably sliding toward civil war over the very institution Parker sought to abolish:

I do not pretend to understand the moral universe; the arc is a long one, my eye reaches but little ways; I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by the experience of sight; I can divine it by conscience. And from what I see I am sure it bends towards justice.[4]

The aim of my book is to show that the Reverends Parker and King were right—that the arc of the moral universe does indeed bend toward justice. In addition to religious conscience and stirring rhetoric, however, we can trace the moral arc through science with data from many different lines of inquiry, all of which demonstrate that in general, as a species, we are becoming increasingly moral. As well, I argue that most of the moral development of the past several centuries has been the result of secular, not religious forces, and that the most important of these that emerged from the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment are science and reason, terms that I use in the broadest sense to mean reasoning through a series of arguments and then confirming that the conclusions are true through empirical verification. (You can order The Moral Arc here.)

Further, I demonstrate that the arc of the moral universe bends not merely toward justice, but toward truth and freedom, and that these positive outcomes have largely been the product of societies moving toward more secular forms of governance and politics, law and jurisprudence, moral reasoning and ethical analysis. Over time it has become less acceptable to argue that my beliefs, morals, and ways of life are better than yours simply because they are mine, or because they are traditional, or because my religion is better than your religion, or because my God is the One True God and yours is not, or because my nation can pound the crap out of your nation. It is no longer acceptable to simply assert your moral beliefs; you have to provide reasons for them, and those reasons had better be grounded in rational arguments and empirical evidence or else they will likely be ignored or rejected.

Historically, we can look back and see that we have been steadily—albeit at times haltingly—expanding the moral sphere to include more members of our species (and now even other species) as legitimate participants in the moral community. The burgeoning conscience of humanity has grown to the point where we no longer consider the wellbeing only of our family, extended family, and local community; rather, our consideration now extends to people quite unlike ourselves, with whom we gladly trade goods and ideas and exchange sentiments and genes, rather than beating, enslaving, raping, or killing them (as our sorry species was wont to do with reckless abandon not so long ago). Nailing down the cause-and-effect relationship between human action and moral progress—that is, determining why it’s happened—is the other primary theme of this book, with the implied application of what we can do to adjust the variables in the equation to continue expanding the moral sphere and push our civilization further along the moral arc. Improvements in the domain of morality are evident in many areas of life:

governance (the rise of liberal democracies and the decline of theocracies and autocracies)

economics (broader property rights and the freedom to trade goods and services with others without oppressive restrictions)

rights (to life, liberty, property, marriage, reproduction, voting, speech, worship, assembly, protest, autonomy, and the pursuit of happiness)

prosperity (the explosion of wealth and increasing affluence for more people in more places; and the decline of poverty worldwide in which a smaller percentage of the world’s people are impoverished than at any time in history)

health and longevity (more people in more places more of the time live longer healthier lives than at any time in the past)

war (a smaller percentage of people die as a result of violent confict today than at any time since our species began)

slavery (outlawed everywhere in the world and practiced in only a few places in the form of sexual slavery and slave labor that are now being targeted for total abolition)

homicide (rates have fallen precipitously from over 100 murders per 100,000 people in the Middle Ages to less than 1 per 100,000 today in the Industrial West, and the chances of an individual dying violently is the lowest it has ever been in history)

rape and sexual assault (trending downward, and while still too prevalent, it is outlawed by all Western states and increasingly prosecuted)

judicial restraint (torture and the death penalty have been almost universally outlawed by states, and where it is still legal is less frequently practiced)

judicial equality (citizens of nations are treated more equally under the law than any time in the past)

civility (people are kinder, more civilized, and less violent to one another than ever before).

In short, we are living in the most moral period in our species’ history.

I do not go so far as to argue that these favorable developments are inevitable or the result of an inexorable unfolding of a moral law of the universe—this is not an “end of history” argument—but there are identifiable causal relationships between social, political, and economic factors and moral outcomes. As Steven Pinker wrote in The Better Angels of Our Nature, a work of breathtaking erudition that was one of the inspirations for my book:

Man’s inhumanity to man has long been a subject for moralization. With the knowledge that something has driven it down we can also treat it as a matter of cause and effect. Instead of asking “Why is there war?” we might ask “Why is there peace?” We can obsess not just over what we have been doing wrong but also what we have been doing right. Because we have been doing something right and it would be good to know what exactly it is.[5]

For tens of millennia moral regress best described our species, and hundreds of millions of people suffered as a result. But then something happened half a millennium ago. The Scientific Revolution led to the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment, and that changed everything. As a result, we ought to understand what happened, how and why these changes reversed our species historical trend downward, and that we can do more to elevate humanity, extend the arc, and bend it ever upwards.

* * *

During the years I spent researching and writing The Moral Arc, when I told people that the subject was moral progress, to describe the responses I received as incredulous would be an understatement; most people thought I was hallucinatory. A quick rundown of the week’s bad news would seem to confirm the diagnosis.

The reaction is understandable because our brains evolved to notice and remember immediate and emotionally salient events, short-term trends, and personal anecdotes. And our sense of time ranges from the psychological “now” of three seconds to the few decades of a human lifetime, which is far too short to track long-term incremental trends unfolding over centuries and millennia, such as evolution, climate change, and—to my thesis—moral progress. If you only ever watched the evening news you would soon have ample evidence that the antithesis of my thesis is true—that things are bad and getting worse. But news agencies are tasked with reporting only the bad news—the ten thousand acts of kindness that happen every day go unreported. But one act of violence—a mass public shooting, a violent murder, a terrorist suicide bombing—are covered in excruciating detail with reporters on the scene, exclusive interviews with eyewitnesses, long shots of ambulances and police squad cars, and the thwap thwap thwap of news choppers overhead providing an aerial perspective on the mayhem. Rarely do news anchors remind their viewers that school shootings are still incredibly rare, that crime rates are hovering around an all-time low, and that acts of terror almost always fail to achieve their objective and their death tolls are negligible compared to other forms of death.

News agencies also report what happens, not what doesn’t happen—we will never see a headline that reads…

ANOTHER YEAR WITHOUT NUCLEAR WAR

This too is a sign of moral progress in that such negative news is still so uncommon that it is worth reporting. Were school shootings, murders, and terrorist attacks as commonplace as charity events, peacekeeping missions, and disease cures, our species would not be long for this world.

As well, not everyone shares my sanguine view of science and reason, which has found itself in recent decades under attack on many fronts: right-wing ideologues who do not understand science; religious-right conservatives who fear science; left-wing postmodernists who do not trust science when it doesn’t support progressive tenets about human nature; extreme environmentalists who want to return to a pre-scientific and pre-industrial agrarian society; anti-vaxxers who wrongly imagine that vaccinations cause autism and other maladies; anti-GMO (genetically modified food) activists who worry about Frankenfoods; and educators of all stripes who cannot articulate why Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) are so vital to a modern democratic nation.

Evidence-based reasoning is the hallmark of science today. It embodies the principles of objective data, theoretical explanation, experimental methodology, peer review, public transparency and open criticism, and trial and error as the most reliable means of determining who is right—not only about the natural world, but about the social and moral worlds as well. In this sense many apparently immoral beliefs are actually factual errors based on incorrect causal theories. Today we hold that it is immoral to burn women as witches, but the reason our European ancestors in the Middle Ages strapped women on a pyre and torched them was because they believed that witches caused crop failures, weather anomalies, diseases, and various other maladies and misfortunes. Now that we have a scientific understanding of agriculture, climate, disease, and other causal vectors—including the role of chance—the witch theory of causality has fallen into disuse; what was a seemingly moral matter was actually a factual mistake.

This conflation of facts and values explains a lot about our history, in which it was once (erroneously) believed that gods need animal and human sacrifices, that demons possess people and cause them to act crazy, that Jews cause plagues and poison wells, that African blacks are better off as slaves, that some races are inferior or superior to other races, that women want to be controlled or dominated by men, that animals are automata and feel no pain, that Kings rule by divine right, and other beliefs no rational scientifically-literate person today would hold, much less proffer as a viable idea to be taken seriously. The Enlightenment philosopher Voltaire explicated the problem succinctly: “Those who can make you believe absurdities, can make you commit atrocities.”[6]

Thus, one path (among many) to a more moral world is to get people to quit believing in absurdities. Science and reason are the best methods for doing that. As a methodology, science has no parallel; it is the ultimate means by which we can understand how the world works, including the moral world. Thus, employing science to determine the conditions that best expand the moral sphere is itself a moral act. The experimental methods and analytical reasoning of science—when applied to the social world toward an end of solving social problems and the betterment of humanity in a civilized state—created the modern world of liberal democracies, civil rights and civil liberties, equal justice under the law, open political and economic borders, free markets and free minds, and prosperity the likes of which no human society in history has ever enjoyed. More people in more places more of the time have more rights, freedoms, liberties, literacy, education, and prosperity than at any time in the past. We have many social and moral problems left to solve, to be sure, and the direction of the arc will hopefully continue upwards long after our epoch so we are by no means at the apex, but there is much evidence for progress and many good reasons for optimism.

* * *

Three years after Dr. King’s “How Long” speech, on April 3, 1968, the civil rights crusader delivered his final speech, I’ve Been to the Mountaintop, in Memphis, Tennessee in which he exhorted his followers to work together to make America the nation its founding documents decreed it would be, foreseeing that he might not live to see the dream realized. “I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you,” he hinted ominously. “But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!” The next day Dr. King was assassinated.

It is to his legacy, and the legacies of all champions of truth, justice, and freedom throughout history, that we owe our allegiance and our efforts at making the world a better place. “Each of us is two selves,” Dr. King wrote. “The great burden of life is to always try to keep that higher self in command. And every time that old lower self acts up and tells us to do wrong, let us allow that higher self to tell us that we were made for the stars, created for the everlasting, born for eternity.”

We are, in fact, made from the stars. Our atoms were forged in the interior of ancient stars that ended their lives in spectacular paroxysms of supernova explosions that dispersed those atoms into space where they coalesced into new solar systems with planets, life, and sentient beings capable of such sublime knowledge and moral wisdom. “We are stardust, we are golden, we are billion-year old carbon…” (from the lyrics of “Woodstock”, by Joni Mitchell).

Morality is something that carbon atoms can embody given a billion years of evolution—the moral arc.

###

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the host of The Michael Shermer Show, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His new book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational. You can order The Moral Arc here.

References

[1] King, Coretta Scott. 1969. My Life With Martin Luther King Jr. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. 267.

[2] Many accounts describe King as being either at the top of the capitol steps, on the steps, or at the bottom of the steps. There are eyewitnesses accounts in which it is claimed that King delivered his famous speech from the steps. For example, John N. Pawelek recalls: “When we arrived at the state capitol, the area was filled with throngs of marchers. Martin Luther King was on the steps. He gave a fiery speech which only a Baptist minister can give.” The Alabama Byways site tells its patrons reliving the Selma to Montgomery march to “walk on the steps of the capitol, where King delivered his ‘How Long, Not Long’ speech to a crowd of nearly 30,000 people. In his book Getting Better: Television and Moral Progress (Transaction Publishers, 1991, p. 48), Henry J. Perkinson writes: “By Thursday, the marchers, who now had swelled to twenty-five thousand, reached Montgomery, where the national networks provided live coverage as Martin Luther King strode up the capital [sic] steps with many of the movement’s heroes alongside. From the top of the steps, King delivered a stunning address to the nation.” Even the Martin Luther King Encyclopedia puts him “on the steps.”

This is incorrect. The BBC reports of the day, for example, say that King “has taken a crowd of nearly 25,000 people to the steps of the state capital” but was stopped from climbing the steps and so “addressed the protesters from a podium in the square.” The New York Times reports that “The Alabama Freedom March from Selma to Montgomery ended shortly after noon at the foot of the Capitol steps” and that “the rally never got on to state property. It was confined to the street in front of the steps.” The original caption to the aerial photograph included in the text, from an educational online source, reads: “King was not allowed to speak from the steps of the Capitol. Can you find the line of state troopers that blocked the way?” This is confirmed by these firsthand accounts: “A few state employees stood on the steps. They watched a construction crew building a speaker’s platform on a truck bed in the street.” And: “The speakers platform is a flatbed truck equipped with microphones and loudspeakers. The rally begins with songs by Odetta, Oscar Brand, Joan Baez, Len Chandler, Peter, Paul & Mary, and Leon Bibb. From his truck-bed podium, King can clearly see Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.”

[3] The speech is commonly known as the “How Long, Not Long” speech (or sometimes “Our God is Marching On”) and is considered one of King’s three most important and impactful speeches, along with “I Have a Dream” and the tragically prescient “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop.” It can be read in its entirety at http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/index.php/kingpapers/article/our_god_is_marching_on/

[4] Parker, Theodore. 1852/2005. Ten Sermons of Religion. Sermon III: Of Justice and Conscience. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Library.

[5] Pinker, Steven. 2011. The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. New York: Viking, xxvi.

[6] Voltaire, 1765. “Question of Miracles.” Miracles and Idolotry. Penguin.

Roland, I am going to stick with the scientific consensus on the subject. You are spreading disinformation and that is unethical.

Michael, here you have authored another outstanding essay. I agree with all your points. I also highly recommend your book The Moral Arc, which I own and have read.

Since no god has ever unambiguously communicated a correct moral code, we are left in the position of inventing one for ourselves. The more we use reason and science for this code, the more we will flourish as a species.