Conspiracy

Why the Rational Believe the Irrational

Today is the publication date of my new book Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational. I have a favor to ask. There is a phenomenon called the Matthew Effect (“to those who have more shall be given”) or accumulated advantage (“people probabilistically accrue a total reward in proportion to their existing degree”) in driving books onto the bestseller list, so the first week of sales is key in getting the word out about a book. To that end I would very much appreciate your support in picking up a copy at your local bookstore or ordering it online here or click on the cover below:

If you prefer listening to books, here is the unabridged audio edition that I read:

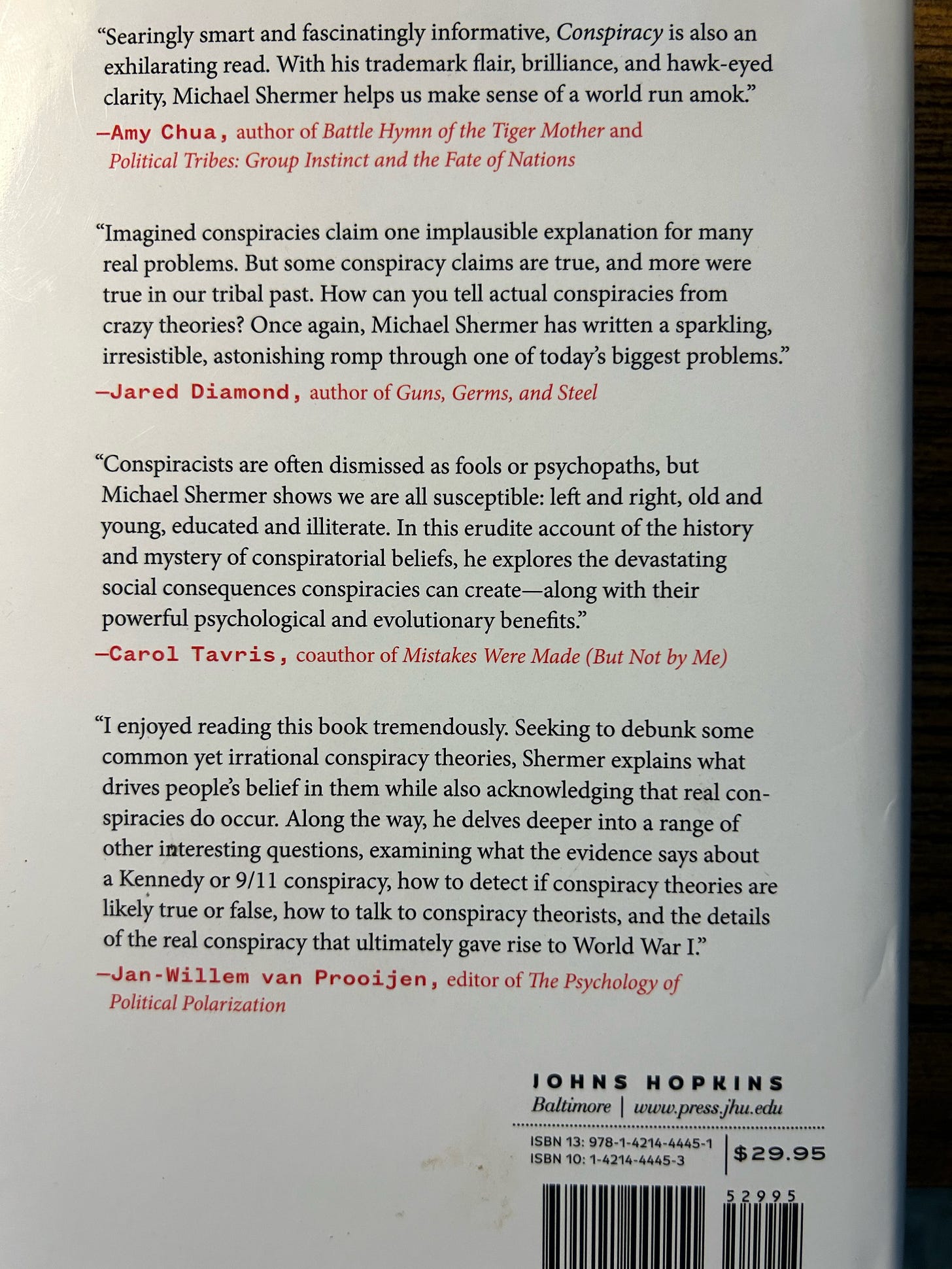

I think this may be my best book to date, or at least the most important, given the elevation of conspiracy theories to the highest levels of our political system. It is no exaggeration to tag the January 6, 2021 insurrection to the rigged-election conspiracy theory, and it is not hyperbole to worry that the 2024 Presidential election may result in similar violence if equally dubious conspiracy theories are proffered by the losing side. Here is the back cover of the book with the advance praise (“blurbs”) it has received:

The book consists of 13 chapters (!) divided into three parts:

Studies show that almost everyone believes at least one conspiracy theory, and evidence I amass in the book demonstrates that conspiracism is not the province of tinfoil-hat wearing wackadoodle weirdos, but is in fact as mainstream as other belief systems. With Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners coming up there will surely be someone at your extended family table who floats a conspiracy theory for discussion—rigged elections, toxic vaccines, global warming, 5G, 9/11, JFK, UAPs, UFOs, globalists, Zionists, Communists et al.—so this book might also be gift wrapped as a present to your conspiratorially-minded family member, friend, or colleague.

In trying to understand conspiracy theories and why people believe them, my theory consists of three overarching factors at work that explain what I am calling the Conspiracy Effect: Why smart people believe blatantly wrong things for apparently rational reasons. They are:

1. Proxy Conspiracism. Many conspiracy theories are proxies for a different type of conspiracist truth—a deeper mythic, psychological, or lived-experience truth. As such, the details and verisimilitude of particular conspiracy theories are less important than the richer truths represented therein, which often contain self-identifying, existential, and moral meanings, often involving power, both for the conspiracist and the perceived conspirators.

2. Tribal Conspiracism. Many conspiracy theories harbor elements of other beliefs, dogmas, and adjacent or preceding conspiracy theories long believed and held as core elements of political, religious, social, political or tribal identity. As such, like proxy truths, current conspiracy theories may serve as stand-ins for earlier conspiracy theories with deep roots in history, and this accounts for the cross-pollination of conspiracy theories and the propensity for people who believe one to believe many, and endorsement of them serves as a social signal of loyalty to the tribe that embraces them as part of the group’s identity.

3. Constructive Conspiracism. The assumption by most researchers of and commentators on conspiracy theories is that they represent false beliefs, which is why the term has become a pejorative descriptor. This is a mistake because, in fact, historically speaking enough conspiracy theories represent actual conspiracies that it pays to err on the side of belief rather than disbelief, just in case. With a lot at stake, especially one’s identity, livelihood, or even life—which was the case during the Paleolithic environment in which we evolved our conspiratorial cognition—it was often better to assume that a conspiracy theory is real when it is not (a False Positive) than to assume it is not real when it is (a False Negative), as the former just makes you paranoid whereas the latter can make you dead.

There is, thus, a mismatch between the rational conspiracism of our evolutionary ancestry, and the modern world filled as it is with a myriad of conspiracy theories so widespread and diverse that discerning truth from falsehood can be exceedingly difficult. To this end I make a distinction between Paranoid Conspiracy Theories involving ultra-secret and über powerful entities for which there is little to no evidence and are largely driven by paranoia, and Realistic Conspiracy Theories involving normal political institutions and corporate entities conspiring to manipulate the system to gain an unfair, immoral, and sometimes illegal advantage over others. Because both history and current events are brimming with real conspiracies, I am arguing that conspiracism is a rational response to a dangerous world and is thus, in the common computer analogue, a feature, not a bug in human cognition. The “apparently rational reasons” in my definition of the Conspiracy Effect is doing a lot of work. I explore those reasons in depth in the book.

Layered on top of these three overarching factors are a number of additional psychological and sociological forces at work in reinforcing belief in conspiracy theories. They include: motivated reasoning, cognitive dissonance, teleological thinking, transcendental thinking, locus of control, anxiety reduction, the confirmation bias, the attribution bias, the hindsight bias, the oversimplification of complex problems, patternicity, agenticity, and more. Think of these as proximate or immediate causes that reinforce conspiratorial beliefs already held for ultimate or deeper causal reasons, such as those overarching factors outlined above.

Finally, I should note that because of the fact that so many conspiracy theories represent real conspiracies, the second half of the book is largely focused on determining the truth or falsity of them. As such, my more objective scholarly voice of the first half of the book is layered with that of my day job as the head of an organization (the Skeptics Society) and the publisher of a magazine (Skeptic) tasked with opining on the verisimilitude of claims people make. That is, I make the case that there is a way to determine the truth value of most conspiracy theories, and I offer my opinion as such on many of the most popular conspiracy theories in history and today.

The problem of today’s conspiracism is urgent—arguably more pressing than at any time in our history—and this is why we need a theory to explain who believes conspiracy theories and why, what evolutionary, psychological, social, cultural, political, and economic conditions fuel them, how to classify and systematize conspiracy theories in order to tease apart their different causes, and how to determine which conspiracy theories might be true, inasmuch as some turn out to be so.

To that end, you might say that we’re all conspiracy theorists now.

Thank you for supporting my work by ordering the print or digital book here

or the audio edition here.

###

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the host of The Michael Shermer Show, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University. Conspiracy is his 15th book.

The story of Trump-Russia collusion is a perfect specimen for anyone interested in studying conspiracy theories. For over two years, it towered over the information landscape and devoured the attention of the media and the public. The total number of articles on the topic produced by the New York Times is difficult to discern, but was estimated to be more than 3,000 during a two-year period, amounting to multiple articles per day. And that is just one newspaper. This was journalism as if conducted under the grips of an obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nearly every report took Trump's guilt for granted. Every day in the news marked the beginning of Armageddon for Trump and his followers.

Michael, why speculate about the motives of other conspiracy theorists when you could have explained why you were one of the most vocal defenders of the Trump-Russia hoax -- the most influential conspiracy theory in recent memory? You could have explained how your hatred of Donald Trump led you to abandon reason and any concern about the absence of evidence supporting your absurd claims. You could have given us some insights into your Trump derangement syndrome. You could have helped us to understand how loyalty to the tribe -- the Democratic Party in this case -- made you eager to lie about and slander not just Donald Trump, but anyone who didn't share your beliefs.

You also could have helped us understand how you came to believe that the lab leak theory was just a "right-wing conspiracy" and a "Trump lie," that Trump paid Russian hookers to pee on a hotel bed because he believed Obama once slept there, that Hunter Biden's laptop was "Russian disinformation," that Kyle Rittenhouse is a white supremacist vigilante, and your many other debunked conspiracy theories.

Of course, I know why you never mention any of that. You have made it a major part of your mission in life -- as well as the mission of Skeptic magazine -- to help the Democratic Party as best you can, which inevitably also means hurting the Republican Party. So, you have hand-picked a few individuals and stories that you feel cast the Republicans in a bad light, while ignoring the conspiracy theories of people like yourself, Hillary Clinton, Stacy Abrams and Barack Obama. You discuss QAnon because that seems like any easy way to make Republicans look bad, even though leftists are actually the only people who have shown much interest in the fringe group. You'll talk about January 6th, but not the Antifa or BLM riots. You'll mention Alex Jones, but not the Democrats who encouraged race riots and attacks on Supreme Court justices.

You like to present yourself as an expert on conspiracy theories so that you can portray anyone who disagrees with you as a nutty conspiracy theorist, while claiming with a phony air of authority that your own conspiracy theories are undeniable truths. You purport to educate us on such matters, but all you really offer is propaganda.

I used to regard you as a defender of science and truth. However, it is becoming increasingly difficult to think of you that way. The difference between your work and that of The View, MSNBC, and AOC is narrowing. I wish you well, but I don't think I'll be helping you to enjoy "the Mathew effect."

It’s nice to see someone pointing out that conspiracy theories are not the exclusive domain of any particular creed—and that they’re often true, or at least truer than the assumption that there’s nothing untoward going on.

But, as in an earlier post about this, I’m not seeing a single explicit or implicit mention of what are by far the most dangerous and pernicious conspiracy theories—the ones spread by officialdom and sanctioned by establishment media—or the daddy of them all: Russiagate. Meanwhile, lists of America’s less rational conspiracy theories go by without mentioning any of the extremely radical and unfounded theories pushed by the left, from Russiagate to systemic -isms.

Why is that?