The assassination attempt on President Donald Trump on July 13 has already spawned a bevy of conspiracy theories. The blood on his ear was that of a theatrical gel pack, which you can supposedly see in his hand as he touches his ear. Trump’s defiant response was staged, as evidenced by the fact that the Secret Service let him back up after tackling him to the ground. The Secret Service let it happen on purpose (LIHOP in conspiracy circles) by waiting for the assassin to take his shot before returning fire. The ladder for the shooter to get on the roof was planted by covert operatives. This was yet another hit ordered by Vladimir Putin. The Chinese want to make sure Trump doesn’t return to the Presidency so they can take Taiwan. The shooter was part of Antifa. Never-Trumper Republicans were behind it. It was a false flag operation.

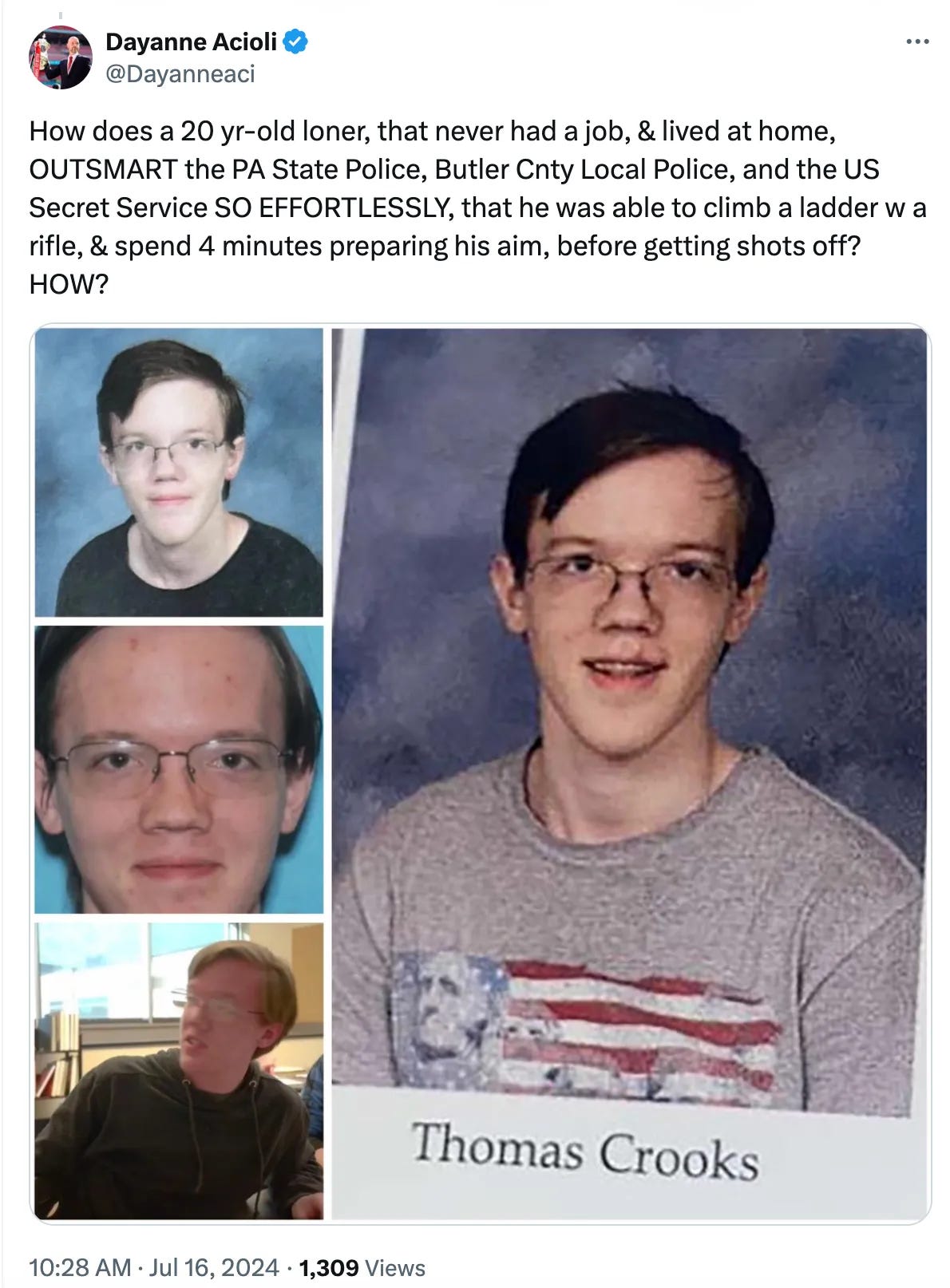

It is early still, and there is much we do not know about Trump’s would-be assassin, Thomas Matthew Crooks, but the odds are long that he was a lone actor and not part of a conspiracy (as I argued in Part I of this series on the history of American political assassinations and assassination attempts). The 20-year old was, in fact, described by acquaintances as a “loner” in high school who was bullied and had “a few friends” but “didn’t have a whole friend group.” He had possession of his father’s legally-purchased AR-15 style rifle, and had in his car dozens of rounds of ammunition and bomb-making materials. Most revealingly, Crooks was allegedly rejected by his high school riflery club for being “comically bad” with a gun. Does this sound like the profile of a highly competent hitman that a crack team of conspirators would contract with to assassinate a former president?

To be sure, there are a number legitimate questions surrounding the incident that need to (and hopefully will) be answered:

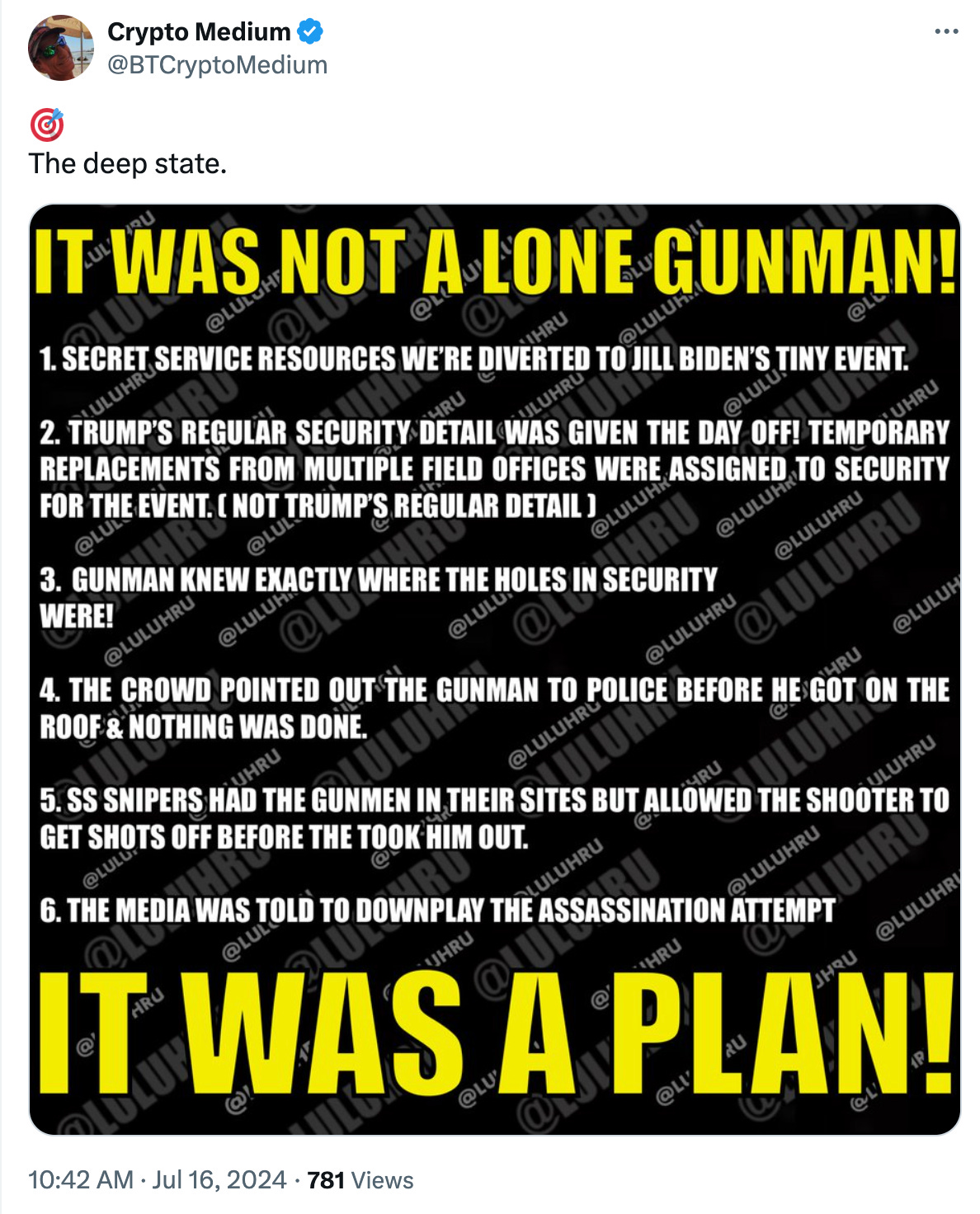

1. Why did the cop who confronted the shooter on the roof not have his gun at the ready so he could engage him instead of standing (or falling) down?

2. The shooter appears to have accessed the roof via a large ladder, but how did that ladder get there in the first place? Was it planted by inside operatives as part of an assassination cabal, or was it there already for some other reason and chance factored into play?

3. The building on which Crooks was perched was, in fact, a staging area for local police, so how did they miss the would-be assassin climbing onto the roof?

4. Since the Secret Service sharpshooter killed the assassin within seconds of initial shots fired, why did he not take the shot first? According to a number of retired Secret Service agents in media interviews, there is no shot-on-warning restriction rule.

5. Why did the Secret Service allow Trump to jump back up to pump his fist and mouth “fight fight fight” to the crowd and expose himself to additional gunfire when they should have kept him down and whisked him away to his bullet-proof SUV?

6. Why did the police not take seriously all the bystanders who saw the gunman on the roof and alerted them about it. Cell phone videos show people pointing and shouting “there’s a man with a gun”, which continues a full 2:00 minutes before shots were fired.

These anomalies—and others—have been compiled into “BlueAnon” conspiracy theories, so named for their doppleganger echo of QAnon conspiracism, but do they represent conspiracy or incompetence on the part of the Secret Service? I was thinking about this question the day before the assassination attempt, in fact, when I was in attendance as a speaker at the annual Freedom Fest conference in Las Vegas, Nevada, along with Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., who famously believes that the CIA assassinated his uncle John F. Kennedy and his father Robert F. Kennedy. The CIA has done some questionable things in foreign countries in the name of national interests there—including assassinating foreign leaders and rigging foreign elections—but murdering their own president (JFK) and possible future president (RFK)?

In the Trump assassination attempt, the Secret Service may have been grossly incompetent—and maybe even criminally negligent—but would they go so far as to assassinate (MIHOP, or Made it Happen On Purpose, in conspiracism jargon) or allow to be assassinated a former president while campaigning to return to the White House? It seems highly unlikely. So why do otherwise rational people believe such seemingly irrational things? In my book, Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational, I attempt to answer this question by outlining a number of factors at work, including:

Event magnitude. The larger the event the more conspiracism surrounds it, as people invest more time and energy into everything that happened in search of some deeper cause. The assassinations of JFK, MLK, and RFK, the deaths of prominent people like Marilyn Monroe and Princess Diana, and terrorist attacks like 9/11, are so large in scope and interest that they draw our attention to examine every detail so scrupulously that everything becomes pregnant with meaning. Attempting to assassinate President Trump constitutes an event of massive magnitude.

Proportionality bias. Large events need large causes. The Holocaust was one of the worst genocides in history and it was caused by one of the worst political regimes in history. There’s a proportionality balance there. The assassination of President Lincoln by a cabal of southern supporters in hopes of reigniting the South’s “war of independence” feels balanced. That JFK, MLK, and RFK were assassinated by lone gunmen, or that Princess Diana’s death in a car crash was the result of speeding, drunk driving and her not wearing a seatbelt, or that 9/11 was orchestrated by 19 guys with box cutters, doesn’t feel proportional, so we turn to deeper conspiratorial causes. A lone loser like Thomas Matthew Crooks almost diverting American political history feels causally disproportional.

Anomaly hunting. Large events lead people to look for anything unusual, especially if it is unexplainable, then glomming on to that anomaly as “evidence” of a conspiracy.

Personal incredulity. If I can’t think of an explanation for anomaly X besides a conspiracy, then that proves there is a conspiracy.

Hindsight Bias. The tendency to reconstruct the past to fit with present knowledge. Once an event has occurred, we look back and reconstruct how it happened, why it had to happen that way and not some other way, and why we should have seen it coming all along.

Patternicity. The tendency to find meaningful patterns in random noise leads to conspiratorial cognition, and all those anomalies in the Trump shooting adds up to a meaningful pattern of conspiracy, at least in the minds of conspiracists.

Teleological thinking. The belief that everything happens for a reason and nothing of importance happens by chance.

With all of these factors at work, it was inevitable that within minutes of the assassination attempt on Donald Trump conspiricism would flood social media. While it is not completely irrational to believe in some conspiracy theories—given that conspiracies do happen and sometimes it is better to be safe than sorry—it is very likely that the attempt to kill President Trump was not part of some nefarious cabal and instead was the act of an unhinged lone actor.

As noted in Part I, keep in mind that in American history four presidents have been assassinated while in office—Abraham Lincoln, James Garfield, William McKinley and John F. Kennedy—and another five presidents survived assassination attempts—Andrew Jackson, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, Gerald Ford, and Ronald Reagan—all of which were by lone assassins, as was the assassination of presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy on June 5, 1968, after a campaign rally in Los Angeles, by a Palestinian named Sirhan Sirhan, who testified in his trial that he killed Kennedy “with 20 years of malice aforethought.”

Thus, the the Conspiracism Principle applies:

Never attribute to malice what can be explained by randomness or incompetence.

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine and author of Why People Believe Weird Things, Heavens on Earth, and Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational. His next book is Truth: What it is, How to Find it, Why it Matters, to be publisher Fall, 2025.

I used to be a Foreign Service officer, and lived overseas in a number of countries where conspiracy theories flourished, particularly about the U.S. and our motives. Our mistakes, in particular, were generally ascribed to some unknown strategic purpose. I would tell people, "Never ascribe to conspiracy something that can be adequately explained by incompetence."

There are many legitimate questions marks and sometimes we just have to admit the naked truth, which is that we don’t know the truth, at least not for the time being.