Expelled!

Kevin Miller offers a solution to the science-religion conflict while exposing the truth behind Ben Stein’s anti-evolution film Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed, on which he worked

“Should I be worried about the Crips and the Bloods up here?” These were the first words out of the mouth of Ben Stein as he entered my office at Skeptic magazine in 2007, located in the racially mixed neighborhood of Altadena, California. I cringed and hoped that the two black women in my employ were out of earshot of what I hoped was merely Mr. Stein’s ham-handed attempt at humor before we settled into his interview of me for what I was told was a film on the intersection of science and religion titled “Crossroads.”

That is not what the film is about, actually titled Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed. Its exegesis is this: Darwinism leads to atheism, Communism, Fascism, and the Holocaust. We are in an ideological war between a scientific natural worldview that leads to the gulag archipelago and Nazi gas chambers, and a religious supernatural worldview that leads to freedom, justice, and the American way. Expelling Intelligent Design from American classrooms and culture will inexorably take us down a path of doom, and the film’s blunt editing intersperses interview snippets from evolutionary biologists with black-and-white clips of, in ascending scale of ominousness, bullies pounding on a 98-pound weakling, Charlton Heston’s character in Planet of the Apes being blasted by a water hose by a gorilla thug, Nikita Khrushchev pounding his fist on a United Nations desk, East Germans captured trying to scale the Berlin Wall, and Nazi crematoria remains and Holocaust victims being bulldozed into mass graves. The formula is unmistakable: Darwinism = Death.

Expelled is pure propaganda that would make even Leni Riefenstahl blush. I wrote one of my Scientific American columns on the film here, and a longer analysis of it in Skeptic in 2008, and to my surprise I recently received correspondence from one of the screenwriters of Expelled, Kevin Miller, who inquired if I would like to know what was really going on behind the scenes in the production of the film. Indeed I would, and here it is.

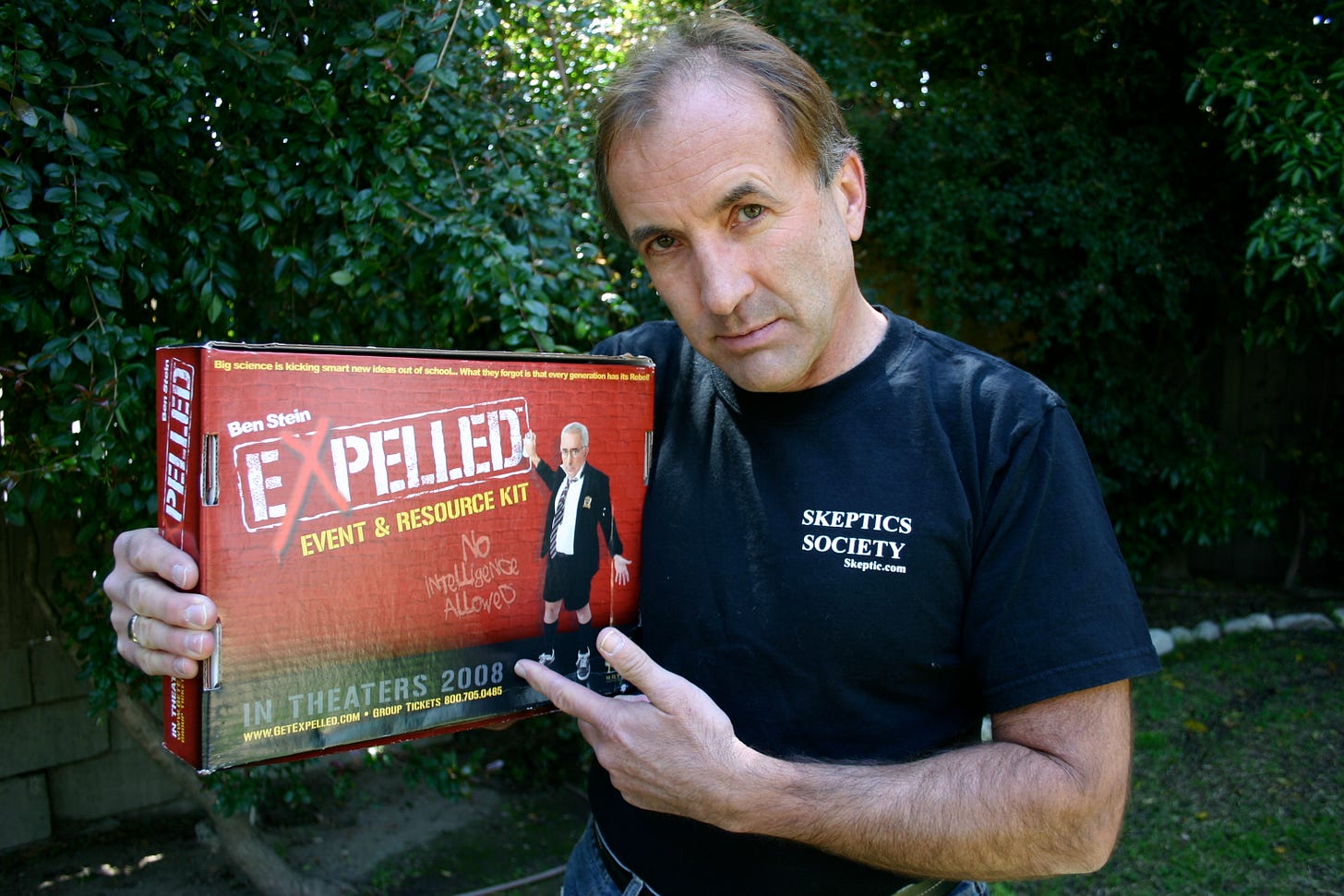

Kevin Miller an award-winning author and filmmaker. He has written, directed, and/or produced several documentary films, including Hellbound?, J.E.S.U.S.A., and No Saints for Sinners. He is also the author of the best-selling Milligan Creek Series for middle-grade readers as well as numerous other books for children and adults, both fiction and non-fiction. Kevin has taught creative writing and screenwriting across the US and Canada as well as in the UK and Australia. To learn more about Kevin and his work, visit www.kevinmillerxi.com. He is pictured below in the Skeptic magazine office holding our Bigfoot track maker shoes.

Expelled!

My role in and the true story behind Ben Stein’s film Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed

Kevin Miller

In 2008 the documentary film Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed was released to widespread media coverage and hype. Starring conservative commentator, actor, and former speechwriter for Richard Nixon, Ben Stein, the film argued that within academia is a conspiracy to censor Intelligent Design (ID) and to cover up evidence that belief in evolutionary theory led to everything from atheism to the Nazi Holocaust. Expelled opened in over 1,300 theaters and earned nearly $8 million. In addition to ID theorists, the film included interviews with proponents of evolutionary theory such as Richard Dawkins, Michael Ruse, William Provine, Eugenie Scott, Christopher Hitchens, and Michael Shermer. As the film’s co-writer, I was part of the crew that came to the Skeptic magazine office to interview Michael Shermer.

Although I was in agreement with the film’s agenda at the beginning, throughout the long production process, my feelings about the project and the ID movement underwent a significant shift. But I stayed on board in the hope of providing a counterbalance to the producers’ desire to produce what amounted to a piece of pro-ID propaganda. As I eventually realized, however, whoever controls the money controls the point of view, so there was only so much that I, a fledgling screenwriter, could do.

In the years since Expelled came out, the transformation of my views has continued apace, so I wrote to Dr. Shermer to apologize for the damage the film did and the duplicitous circumstances under which some of our interviews were obtained. In response, he invited me to write an article describing my experience on Expelled as well as my subsequent reflections on the ID movement and the larger issue of the relationship between science and religion.

During the two and a half years I spent working on Expelled, one of the key dynamics I observed was how bitterly divided people were over the notion of ID as a concept, and even more so as a movement. After reading countless books and articles on the subject and participating in interviews with people on all sides, I realized that no matter which way one approached the topic of evolution and intelligent design—and by extension, science and religion—the individuals on the frontlines were virtually all highly intelligent people of goodwill. Unfortunately, some of the leading voices were also exceedingly pugilistic by nature. Thus, rather than engage in dialogue that sought to establish common ground and then work together to build bridges toward truth, interactions between the ID movement and its critics often amounted to one side lobbing a grenade at the other and then hunkering down in the trenches as it exploded, all the while chuckling about how foolish the folks on the other side were. Rather than emulate that spirit, I decided I would try to engage my critics in constructive conversation instead, to see if it was possible to cross no man’s land and find some sort of common bond with the “enemy.”

Over the several weeks leading up to the film’s release, I did exactly that, spending hours each day engaging with people on my personal blog and other online forums. Despite my legitimate desire to dialogue with my opponents, my efforts were often met with an unrelenting wall of bitterness and sarcasm. Perhaps not surprisingly considering the relentless barrage of abuse, despite my good intentions I occasionally succumbed to a similar rhetorical approach, adding a heavy dose of sarcasm to my own barbed responses. Even so, I was truly seeking to abide by motivational speaker Steven Covey’s “highly effective” habit number five: seek first to understand, then to be understood.

Over time, I recognized a pattern across the various responses I was receiving, one that matched a famous quote by Richard Dawkins: “It is absolutely safe to say that if you meet somebody who claims not to believe in evolution, that person is ignorant, stupid or insane (or wicked, but I’d rather not consider that).” On the surface, this sounds like an incredibly arrogant thing to say, relegating one’s opponents to varying levels of intellectual inferiority, insanity, or iniquity. But as I thought about it, I realized that’s how many of us treat those who don’t share our beliefs. When we encounter someone who disagrees with us, at first we assume they simply don’t know what we know, so we attempt to educate them. If that fails, we may briefly entertain the idea that the person is incapable of understanding the truth. But if they display a reasonable level of intelligence, we seem to be left with only two options: either they know what we know to be true, and they’re purposely suppressing or obscuring that information (which puts them in the wicked category), or they’re so out of touch with reality that they’re a lost cause.

This was exactly the continuum I found myself traveling along with my Neo-Darwinian debating partners. While, in their minds, I made a brief stop at “ignorant,” once I demonstrated that I was reasonably well informed on the relevant issues, they quickly shuffled me into the “wicked” category, with brief stopovers at “stupid” and “insane.” Their favorite name for me was “liar,” which I found frustrating because, despite how one might interpret the rhetorical position of Expelled, a film in which I had authorial influence but no editorial control, I wasn’t trying to be deceptive at all. I was sincerely seeking the truth, not claiming to have it.

In retrospect, though, I empathize with my opponents’ frustration. My stubborn refusal to concede my views probably led them to believe their efforts to correct my faulty thinking were in vain, but little did they, or I, realize the long-term effect that those interactions would have on my life. That’s because even though I was championing a documentary that many regard as an anathema to science—and truth in general—long before the film’s release, cracks had begun to form in my own beliefs about the ID movement and the branch of evangelical Christianity to which I had converted as a child.

The process began about six years before I signed on to Expelled when I took a class on science and Christianity at Regent College—a seminary in Vancouver, BC—co-led by historians Mark Noll and David N. Livingstone, author of Darwin’s Forgotten Defenders. That class served as a rebuttal to the commonly held belief that evolution and Christianity are inherently at odds. As Livingstone outlines in his book, the initial Christian response to Darwin’s theory was characterized by accommodation rather than confrontation. Rather than refute Darwin’s theory, many theologians focused on harmonizing evolution with the notion of divine design instead. It wasn’t until the rise of Christian fundamentalism in the early twentieth century, which lumped evolutionary theory together with higher criticism and other attacks on a literal approach to the Bible, that a split between evolutionary science and some branches of Christianity developed.

Noll and Livingstone’s class triggered a hunger to go deeper into the subject, leading me to focus on epistemology in general and the philosophy of science in particular. I was fascinated by the concept of warranted belief and the reliability of belief-producing processes. Are humans capable of discerning truth? If so, how? Does objective truth even exist? If so, is it possible to know it?

While my belief in God was still relatively intact at that point, by the time we started development on Expelled in late 2005, the epistemological ground beneath me had shifted. I don’t recall when it was exactly, but sometime over the next six months, I was in a coffee shop doing research for the film when I ran into my pastor and confessed that I no longer believed in Satan, angels, or demons. I do, however, recall the look of deep disappointment on his face.

My confession was as much a revelation to me as it was to him. I can’t point to any one thing that led to that conclusion, but by then I had steeped myself in the writings of those at the forefront of the fight against ID, including Daniel Dennett, Richard Dawkins, Michael Shermer, Kenneth Miller, Michael Ruse, Eugenie Scott, Sam Harris, and others. I had also read and interacted with several leading proponents of the ID movement, including Stephen Meyer, David Berlinski, William Dembski, Philip E. Johnson, and Michael Behe. Altogether, the more my understanding of the relevant science grew, the less work there seemed to be for God to do in the universe. No matter what gap in our knowledge one could point to, claiming God’s handiwork could be found hidden there, the history of science appeared to be one long, inexorable march toward shining a light into those very gaps, revealing not God but the same natural processes we observe today, removing the need to resort to divine intervention as a cause.

To my way of thinking, that didn’t necessarily negate the concept of God or some sort of guiding intelligence in the universe, but even if such a being existed, it seemed like the most one could say was that “life, the universe, and everything” were the product of secondary rather than primary causes. God may have created the scale by which all things are measured, but apart from a few moments where a nudge in the right direction was required, his finger was never on it.

This put me in an ideal frame of mind to accept the primary claims of the ID movement. Many proponents of ID accept most aspects of the Neo-Darwinian synthesis, agreeing that the majority of what we observe in the universe is the product of secondary causes. However, while ID proponents agree that natural selection can account for relatively minor changes within species, they argue that it is wholly inadequate when it comes to explaining the origin of species or life itself, not to mention the origin of the universe. Not only do ID proponents believe life is too complex to be attributed to blind natural causes, they also argue that it is “irreducibly complex,” as Michael Behe puts it, wherein “a single system which is composed of several well-matched interacting parts that contribute to the basic function, wherein the removal of any one of the parts causes the system to effectively cease functioning” could not possibly be the product of a gradual process because the system’s function couldn’t be selected for until all the pieces were in place.

Furthermore, ID proponents like William Dembski and Stephen Meyer argue for something called “specified complexity,” whereby if something exhibits both complexity and specificity (i.e., information), one must infer that it is the product of intelligence, seeing as intelligence is the only source of information that we are aware of in the universe. Hence, even if blind, natural processes can account for how that information is edited (something else that ID proponents dispute), such causes can’t explain how that information arose in the first place, much less how the universe in which that information is processed came into being.

Of course, opponents of ID have no end of rebuttals to these arguments. Primarily, as Richard Dawkins argued in his 2006 book The God Delusion, rather than end the argument regarding origins, proposing an intelligent designer to account for irreducible or specified complexity merely punts the ball down the field because such a designer would have to be the product of the same processes as the phenomenon the designer is invoked to explain. So, as Shermer articulates it in his 2005 book Why Darwin Matters, if complexity necessitates an intelligent designer, then there must be a super-intelligent designer, which itself necessitates a super-duper-intelligent designer, and so on in an infinite regress.

Despite such objections to ID, I realized both sides of the debate faced the same sort of infinite regression when it came to explaining origins. Just as positing a designer merely postpones the problem, so does a purely materialistic point of view, with natural selection seemingly incapable of providing an account for how it came to be without resorting to itself. The same goes for the seemingly immutable laws of nature within which natural selection operates. We have all sorts of theories for how these forces might have come into being and what holds them constant, but as for an ultimate explanation for the origin of the laws of nature, no one knows for sure. Accordingly, it appeared to me that on a philosophical level at least, ID’s proponents and its materialist critics were on equal footing. Each side was proceeding from a set of unprovable philosophical presuppositions about how the world came into being, but they were also equally certain that the other side’s philosophical presuppositions were wrong.

To add another level of similarity, many individuals on each side claimed that their presuppositions were a scientific inference rather than a philosophical preference. That is, they insisted their axiomatic beliefs were a product of their scientific observations rather than something they brought to the table with them beforehand, only to have those beliefs consciously or subconsciously influence their scientific observations, thus conforming them to what they already believed.

When it came to Expelled, it was this interplay between philosophical presuppositions and the day-to-day practice of science that interested me most. After all, any honest observer has to admit that philosophical presuppositions affect how we approach science, determining what is and is not accepted as evidence, for example. At the same time, a truly scientific person must always be willing to revise their presuppositions in light of new evidence and/or arguments. My highest hope for the film was that it could explore this reciprocal relationship between science and philosophy, leading to the very common ground that I had sought to establish with my online debating partners. Perhaps operating from a place of naïve optimism, I hoped the film could do away with the need to “win” the debate over ID one way or the other and instead unite these great minds around their mutual desire to move science forward.

Alas, that was not to be. For one thing, early in the process of making Expelled, I realized that the film’s producers weren’t interested in open-minded inquiry. They had an axe to grind against what they saw as an oppressive scientific establishment that was unwilling to “allow one divine foot in the door” (as geneticist Richard Lewontin put it), and they were determined to change that. Initially, I bought into this agenda as well, feeling like we were on the right side of history because we were fighting for free and open inquiry, not just on behalf of ID but also on behalf of science itself. Why shouldn’t scientists be able to follow the evidence wherever it leads, as Stephen Meyer puts it? And why shouldn’t intelligence be considered as a potential explanation for particular phenomena until proven otherwise? Hadn’t a presumption of theism, or at least deism, guided most of the early scientists, leading to all sorts of fruitful inquiry? If so, why couldn’t that continue?

Ironically, the fact that the producers were working with the Discovery Institute prevented the film itself from pursuing Meyer’s ideal of inferring to the best explanation. I remember one night when we showed an early cut of the film to Meyer and his associates that led to a hasty closed-door meeting between them and the producers. When they emerged later that evening, we were informed that the film would be delayed by several months until it was recut to the Discovery Institute’s satisfaction. Otherwise, they refused to promote it, and without their partnership, the film would be DOA—dead on arrival.

Ben Stein’s involvement was another complicating factor. While he resonated with the apparent injustice of scientists being disqualified due to their religious beliefs, his main interest in Expelled appeared to be invalidating evolutionary theory by associating it with the horrors perpetuated by the Third Reich, something that many of us on the production team were leery of. For, if the Holocaust could be blamed on evolution, couldn’t it also be blamed on the Bible, seeing as that also had a heavy influence on Hitler’s beliefs? The best one could say is that Hitler’s erroneous interpretations of these and many other factors led to the evils that the Nazis committed. It would be absurd to disown Neo Darwinism, the Bible, or anything else that inspired Hitler as guilty by association.

My interactions with some of the leading lights of ID also had a chilling effect on my belief that we were on the right side of the debate. For example, when Ben Stein asked Michael Behe how biology would be different if it had ID theory as its foundation, Behe was left groping for an answer. Then when Stein was interviewing David Berlinski outside the Berlin Wall, trying to coax him into saying that an unnecessary ideological wall had been erected to keep any notion of God out of science—just as the Berlin Wall had been erected to keep “dangerous” ideas out of the Soviet Union—Berlinski refused to acquiesce. Instead, he insisted that we need boundaries in science to help define the field. For example, we don’t accept astrology as part of science, nor should we. Walls aren’t bad in and of themselves, Berlinski argued; it’s more a matter of where we build them and why.

Of course, how we make this determination is a product of our philosophical presuppositions, which are becoming increasingly impossible to agree on as we all break away from traditional metanarratives and drift off into our own private definitions of reality. But even if we don’t agree with some or all of a field’s presuppositions, if we presume competence and goodwill amongst scientists, it’s only logical to assume that these boundaries exist not to limit the production of good science but to facilitate it. Otherwise, we find ourselves in the absurd position of arguing that scientists are working against their own self-interest.

I realize that a presumption of competence and goodwill is increasingly difficult to maintain these days as our confidence in the integrity of various institutions wanes. The problem is, considering the increasing complexity of the modern world, we are facing what energy theorist Vaclav Smil describes as a growing “comprehension deficit,” which makes our need to rely on experts greater than ever. This being the case, how can we determine when a dissident group, like the ID movement, who is challenging the majority opinion in a field is correct or whether they are a destructive force that really should be “expelled” out into the cold?

I continue to believe that a presumption of competence and goodwill amongst experts is the most fruitful and cognitively healthy way to proceed. Therefore, I’m willing to go with the majority view in any given field until given good reason to think otherwise. But I have to admit I’m far more skeptical than I used to be. And who doesn’t love the idea of a plucky group of rebels who risk everything to stand up to the oppressive, corrupt authorities, vowing to “drain the swamp” and restore freedom, truth, and justice to the masses? Everyone from political leaders like Vladimir Lenin and Donald Trump to storytellers like George Lucas have exploited this universal narrative, which is becoming increasingly attractive as we all sense a growing lack of control over our circumstances due to the increasing pace and complexity of change, technological and otherwise.

This was exactly the narrative that we sought to tap into when making Expelled, knowing it would resonate with viewers on an emotional level. The question is, were we right when it came to the ID movement? Were they really akin to the Rebels in Star Wars, virtuous dissidents standing up against the evil Darwinian empire? I certainly believed it at the time, but I no longer think so now.

Despite the radical change in my views, fifteen years after Expelled I can’t say I regret being involved with the film. It provided me with a blank check to indulge my passion for research, to travel the world, to meet some of the brightest minds in science, to work with people who eventually became some of my closest friends, and to establish myself in the film industry. More importantly, over the long term, it completely transformed my view of life and culture, bringing me much closer to those whom I used to regard as standing on the opposite side of the aisle. But I do have significant regrets about how the film itself turned out, the distrust it sowed amongst viewers regarding the scientific establishment, and the deceptive practices we engaged in to make the film happen.

One example of those deceptive practices was hiring hundreds of extras to serve as Ben Stein’s “audience” during the speech he gives that bookends the film, making it seem as if he’s leading a groundswell of young people who are looking to overthrow the tyrannical Darwinian academy. This was filmed at Pepperdine University, Dr. Shermer’s alma mater, so he wrote them to ask how this happened:

The biology professors at Pepperdine assure me that their mostly Christian students fully accept the theory of evolution. So who were these people embracing Stein’s screed against science? Extras. According to Lee Kats, Associate Provost for Research and Chair of Natural Science at Pepperdine, “the production company paid for the use of the facility just as all other companies do that film on our campus” but that “the company was nervous that they would not have enough people in the audience so they brought in extras. Members of the audience had to sign in and the staff member reports that no more than two to three Pepperdine students were in attendance. Mr. Stein’s lecture on that topic was not an event sponsored by the university.” And this is one of the least dishonest parts of the film.

Another was creating a fake production company, complete with a website listing several dummy film projects. We used this website to mislead potential interviewees into believing we were taking an objective approach to the subject matter, which couldn’t have been further from the truth. I’ve been involved in several controversial documentaries since Expelled, and landing interviews with potentially hostile subjects is always a challenge. In such circumstances, I admit to being less than forthcoming about my point of view at times because I’d rather get a “clean read” than a confrontational exchange, a relaxed conversation where the subject expresses their views similar to how they might talk to a friend, but not since Expelled have I taken things to such an extreme.

Like anyone who believes they have the truth (or possibly even God) on their side, while making Expelled we felt the ends justified the means. As history shows time and time again, though, just when we think we’re most virtuous, we’re also at our most dangerous. When facing off against what we regard as a great evil, belief in our own righteousness can blind us to the very evils we ourselves are committing in response.

If Expelled had been made today, it probably would have been called Canceled or Blocked instead because too often when we encounter ideas that offend our philosophical presuppositions, our emotional sensibilities, or our fragile sense of identity, that’s exactly what we do. And unlike the way the scientific establishment is portrayed in Expelled, it’s not just those in authority who do this. More often than not these days, mobs of regular people are leading the charge. Driven by a sense of self-righteousness and/or a weaponized form of compassion, they summarily destroy people’s lives, due process be damned.

Despite this discouraging state of affairs, I still believe in the power of conversation and debate as perhaps the only way forward. After all, it worked to change my mind (eventually), so why couldn’t it work for others?

Lack of common ground, a shared version of reality in which to engage, remains a problem. And with traditional means of establishing this common ground, such as religion, which is rapidly fading away, it seems like an impossible goal to achieve. But if we continue to expel, cancel, and block each other over our differences of opinion rather than dialogue and partner together to share our unique perspectives, there really is no hope for science, freedom, or truth. We may never be able to achieve unanimity of belief, but if we can at least aspire toward unity of purpose and intent, agreeing to operate from a position of goodwill, charity, and curiosity rather than selfish gain or the need to bolster our identity by scapegoating others, maybe we can find a way to work together despite our differences as we fumble toward increasingly more constructive models of reality.

Expelled itself may not exemplify these virtues, but if it can at least become an object lesson for how not to do things, maybe even it can play a role in this process.

I am an atheist, but I think there is an important role for traditional religion in a modern mostly secular society. Religion is a way to put on the brakes when technological or cultural chenge becomes too fast or goes too far.

It is a way to consult the collective wisdom of our ancestors, to ask them what they would think about things. We do not have to listen to them, but it is good to have a way to ask the questions before rushing headlong into assisted fertilization, human-computer merging, genetic manipulation, geoengineering, and other developments that at least some religions oppose.

Religion also is a good thing in providing a counter to the modern all-powerful state. It is very important to have at least a few people who do not recognize the state as the ultimate authority. Who insist there is some higher authority to which they give their ultimate aligence. Without them it becomes the state that can demand total control.

We saw this during the recent covid panic, when governments ignored and abandoned rights that were established over centuries and not without much bloodshed, and in many case it was the religious people, and especially the most religious, those we tend to label as fanatics, who stood up to the imposition of a medical dictatorship and resisted the tyranical demands of those who give too much authority to both modern science and the state it exists to serve.

So while I do not believe in any religion, I am glad somebody does. If we need to fight for our liberties, they will be among our best allies.

As for the conflict between Darwinism and the Judeo-Christian story of creation, that is not so immportant as both sides think it is. They have more in common than either will admit. After all, they both agree that life began a long time ago and has continued ever since by the well-known process of reproduction. They only differ on the minor point of exactly how it began.

The real challenge to both Darwinism and the Genesis story, both of which have serious shortcomings, is the now-abandoned theory of spontaneous generation, the claim that life, as a perfectly natural phenomenon, will naturally occur wherever and when ever the conditions are right for it and that the conditions under which it can be found thriving today are the right cconditions for it to first occur.

This theory of natural self-organization of living forms coming into existence all around us all the time, and mutlually adapted to the conditions under which they form, including others forming at the same time and place, better explains the diversity of living forms and the mutual adaptation of multiple species in an ecosystem than any theory that requires all living things today to be descended from ancestors.

Natural self-organization of living organisms happens all around us all the time, but is almost never observed by scientists due to their heavy indoctrination against it, although many uneducated rural folk are well aware of such things and frequently observe it happening in the woods, fields, and ponds.

The Creationists and the Darwinists have both done an excellent job of discovering the flaws in each others theories, but neither makes a really good case. A third viewpoint is badly needed and a modernized form of spontaneous generation, not just of individual species, but of ecosystems, is the most viable contender.

Thank you for this post. I think it might help me work through some issues I’m having with my feelings toward those whom I view in much the same way I view the ID community – that being virus deniers. I recently wrote a piece in which I outline my understanding of colds and how they happen.

And I now realize it might be a way to bridge the divide between those like me who believe in science and those like virus deniers who generally do not. Because though I believe in what they call “germ theory,” I do not believe viruses play THE causative (or as lawyers would say “dispositive”) role in the creation of colds.

What I feel is that colds happen when we are in a hyper-exhausted, angry, aggravated and frustrated state of mind. A cold happens because of how that state of mind, and the type of breathing that results, irritates our nasal passages causing acute rawness there. The body then treats that rawness by creating a build-up of mucus to soothe that soreness, which rather quickly creates a condition we call the common cold.

I fully realize how ridiculous this hypothesis sounds to most people. But that understanding has kept me cold free for many years. And no one who has been fully exposed to my explanation has offered any evidence of its fallacy, quite the opposite. Meanwhile in all the years the scientific community has been studying colds, it has found no proof of the role of viruses, and no way of preventing colds, despite their omnipresence.

So I feel my article to be the perfect way to narrow the divides between our ways of thinking. I hope that virus deniers will embrace it, because of the proof it might offer that at least one supposedly contagious disease is not caused by viruses or any other pathogen. And it seems to me it could also be a way to have the scientific community show a little humility – which I see as being much needed, especially in light of their failures during the Covid crisis, and how much science skepticism that has created.

Science doesn’t know everything – yet. And until it does, it seems to me a little humility might be in order. In any case, for those who might be interested, here’s a link to How Did You Catch That Cold?

https://theprogressivecontrarian.substack.com/p/how-did-you-catch-that-cold