Extraterrestrial Governance

We are about to become a multi-planetary species. What type of government should be established on other planets, moons, and space-faring civilizations?

The following (shortened) article is my contribution to an edited-volume published by Oxford University Press in 2023, The Institutions of Extraterrestrial Liberty, edited by the University of Edinburgh astrobiologist Charles Cockell, whose work explores the social, political, and economic dynamics of long-term space settlement.

“But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.” —James Madison, Federalist Paper No. 51

We are about to establish settlements on the Earth’s moon and on Mars in the next few years or decades. Given that future solar system settlers will have similar biological natures as our Paleolithic colonists had when they undertook their exploration and settlement of Earth out of Africa, it would be prudent to start thinking about how best to govern an extraterrestrial civilization, starting with what we have learned already from the scientific study of governance on our planet.

I started thinking about this issue when Elon Musk announced his intention to set up a Martian colony before the end of the 2020s, explaining his motivation to a 2018 South by Southwest (SXSW) conference audience thusly: “If there’s a third world war we want to make sure there’s enough of a seed of human civilization somewhere else to bring it back and shorten the length of the dark ages,” adding that the endeavor will be “difficult, dangerous, a good chance you’ll die.” Curious to know his thoughts on the subject of extraterrestrial governance, on June 16, 2018 I whimsically tweeted at the SpaceX CEO:

Minutes later I received this reply from Musk:

Given that Twitter may not be the ideal platform for fleshing out complex thoughts like establishing a new governing system on another planet, I thought Musk’s additional comments to the SXSW attendees were revealing:

Most likely, the form of government on Mars would be somewhat of a direct democracy where people vote directly on issues instead of going through representative government. When the United States was formed representative government was the only thing that was logistically feasible. There was no way for people to communicate instantly. A lot of people didn’t have access to mailboxes, the post office was primitive. A lot of people couldn’t write. So you had to have some form of representative democracy or things just wouldn’t work at all. On Mars, everyone votes on every issue and that’s how it goes. There are a few things I’d recommend, which is keep laws short. Long laws...that’s like something suspicious going on if there’s long laws.

That certainly sounds reasonable. Who wouldn’t prefer fewer laws and more freedom? Unfortunately, most people on both the political left and the political right appear to want more laws, inasmuch as both parties have all reliably grown the size the government in their charge. And it is why libertarian sentiments, so succinctly expressed in the title of Matt Kibbe’s libertarian manifesto Don’t Hurt Other People and Don’t Take Their Stuff, are embraced by so few people (the Libertarian party is lucky to get even one percent of the vote in national elections).

The reason is to be found in the nature of human interaction and conflict resolution, which grow exponentially as small bands and tribes coalesce into larger chiefdoms and states. Musk’s direct democracy could be effective with a few dozen inhabitants, which is roughly the size of hunter-gatherer bands. But look what happens as population numbers increase through both fecundity and immigration—both of which are likely in an initial extraterrestrial founding colony—as worked out by the UCLA geographer Jared Diamond from his studies of the hunter-gatherer peoples of Papua New Guinea: a small band of 20 people generates 190 possible dyads, or two-person interactions (20 x 19 ÷ 2), small enough for informal conflict resolution. But increase that 20 to 2,000 and you’re facing 1,999,000 possible dyads (2000 x 1999 ÷ 2). Here a 100-fold population increase produces a 10,000-fold dyadic rise. Scale that up to cities of 200,000 or 2,000,000 and the potential for conflict multiplies beyond comprehension, along with it laws and regulations needed to insure relative harmony and efficiency. As Diamond explains in his book Guns, Germs, and Steel:

Once the threshold of “several hundred,” below which everyone can know everyone else, has been crossed, increasing numbers of dyads become pairs of unrelated strangers. Hence, a large society that continues to leave conflict resolution to all of its members is guaranteed to blow up. That factor alone would explain why societies of thousands can exist only if they develop centralized authority to monopolize force and resolve conflict.

Let’s apply this analysis to what Musk has in mind when he says that “the threshold for a self-sustaining city on Mars or a civilization would be a million people.” That number generates nearly 500 billion dyadic combinatorial possibilities (1,000,000 x 999,999 ÷ 2 = 499,999,500,000), meaning any hoped-for manual of “short laws” would soon become volumes of bureaucratic regulations and laws, which as we know from history results in complex political and legal systems of suffocating regulations, entangling restrictions, government overreach, and suppression of individual freedom and autonomy. Extraterrestrial explorers and settlers will need to figure out how to prevent a bureaucracy from expanding in response to the accelerating dyadic combinations as their population increases, which has happened in every government on Earth as if it were a law of nature.

Thus, the general challenge for Martians is the same as it has been for Earthlings for millennia: to strike the right balance between freedom and security. It would be interesting for Martian colonists to experiment with and design new systems of governance never tried on Earth, but these Martians will be Earthlings with all the inner demons that come bundled with the better angels of our nature.

To many people, the idea of humans settling down on an extraterrestrial body sounds overly optimistic, highly improbable, and even hallucinatory. “The idea of Elon Musk to have a million people settle on Mars is a dangerous delusion,” said the Astronomer Royal Lord Martin Rees. “Living on Mars is no better than living on the South Pole or the tip of Mount Everest.” Indeed, but that is surely what it must have seemed to our Paleolithic ancestors who—barely eeking out a living in the nooks and crannies of sub-Saharan Africa and Ice Age Europe in the evolutionary bottlenecks that nearly exterminated our species some tens of thousands of years ago—nevertheless over those long gone millennia spread out across all of Earth’s continents and, eventually, island hopped their way across the vast Pacific Ocean, which must have seemed as daunting to those early explorers as interstellar space appears to us today.

Given our species’ exploratory nature and its propensity to widen our horizons by branching out from our home territories to put down stakes and settle new lands, it is not completely crazy to imagine how interstellar and even galactic civilizations might develop. Founder populations on the moon and Mars could eventually spread themselves throughout the solar system, establishing communities on the moons of Jupiter and Saturn and, in the fullness of time and with new propulsion technologies (we’re talking centuries, if not millennia), cross the vast distances of interstellar space and over millions of years star hop their way around the galaxy.

What might happen with our moral and political nature? Assuming that we are not going to genetically engineer out of our nature greed, avarice, competitiveness, aggression, and violence—given that these characteristics are essential to who we are as a species and all have an evolutionary logic to them—as we branch out across the galaxy there will not be one civilization, but many, not one hominin species, but multiple. Given the distances and time-scales involved, there will likely be many species of spacefaring hominins in which each colonized planet will act like a new “founder” population from which a new species evolves, reproductively isolated from other such populations—the very definition of a species. These civilizations will vary even more than nations on Earth varied before globalization, with dozens, hundreds, possibly even thousands of different civilizations in which sentient beings may flourish—a vast array of peaks on the galactic political landscape.

If this were to happen, sentience itself would become immortal, inasmuch as there is no known mechanism—short of the end of the universe itself trillions of years from now in our accelerating expanding cosmos—to cause the extinction of all planetary and solar systems with all their different sentient hominin species at once.

In the far future, civilizations may become sufficiently advanced enough to colonize entire galaxies, genetically engineer new life forms, terraform planets, and even trigger the birth of stars and new planetary solar systems through massive engineering projects. Civilizations this advanced would have so much knowledge and power as to be essentially omniscient and omnipotent. (I call this extrapolation Shermer’s Last Law: Any sufficiently advanced extraterrestrial intelligence is indistinguishable from God.) If this also sounds delusional, recall that as long ago as 1960 the physicist Freeman Dyson showed how planets, moons, and asteroids could be torn apart and reconstructed into a giant sphere or ring surrounding the sun to capture enough solar radiation to provide limitless free energy. There are today, in fact, astronomers and organizations searching for signs of such extraterrestrial technologies in our galactic neighborhood, such as Dyson spheres or ETI probes.

Any such civilization could not achieve this level of development without also being advanced politically, economically, and morally as well.

If we do establish extraterrestrial bases, colonies, cities and eventually civilizations, how will they be governed? A number of scientists and science fiction writers, reflecting on the establishment of colonies on other worlds, have made the analogy of Europeans colonizing the Americas, but this only goes so far given the fact that those incipient settlers at least had air to breath, water to drink, and plenty of potential food on the hoof, in the ground, and in oceans, lakes, and rivers. The lack of these basic commodities generates additional problems for the political governance of Mars and other celestial bodies—there’s no air or food! As well, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty that the U.S. signed prohibits anyone from “owning” Mars. What would be the incentive to colonize Mars if there’s no guarantee that the work you do to live there would result in any type of ownership? Although working the land and air to produce resources is not directly proscribed by the treaty, doing so in a manner that doesn’t lead to tyranny is another matter entirely.

These and related problems were addressed by the University of Edinburgh astrophysicist Charles S. Cockell in a series of meetings with scientists and scholars from varied fields in two conference proceedings titled Human Governance Beyond Earth and The Meaning of Liberty Beyond Earth. To learn more about what to do when the most basic necessities of life—oxygen, water, and food—are under the control of one company (SpaceX?) or one government (the U.S. of Mars?), I spoke with Dr. Cockell on my podcast, starting with the observation that Earthlings colonizing Mars will be nothing like Europeans colonizing North America. “Space is an inherently tyranny-prone environment,” Cockell told me. “You are living in an environment where the oxygen you breathe is being produced by a machine.” On Earth, he notes, governments can rob their people of food and water, “but they can’t take away your air, so you can run off into a forest and plan revolution, and you can get your friends together and you can try to overthrow a government.”

In habitats on the moon or Mars where oxygen production is controlled by a single entity, there must be some guarantee that the air supply cannot be cut off to citizens. It would seem, then, that common ownership of the air and the machines that produce it through a single entity would follow, and I suggested as much to Cockell. To my surprise he responded, “I would go in completely the opposite direction. I would fragment as much as possible. I would try to create plurality in the means of production and great competition and have many people able to produce oxygen. So what you’re trying to do is decentralize,” he and his team concluded after studying Earth-bound systems, because “centrally planned governments generally end up as not very good experiments.”

What about corporations that capture a majority market share and become so dominant that they can monopolize the market and turn tyrannical, I inquire? “Well, these things happen on the Earth,” Cockell historicized, noting that documents like the Bill of Rights are designed to keep tyranny in check. True, but not without violence, revolutions, and wars, I rejoin. “It’s hard work to get people to believe in freedom and to fight for it,” Cockell admitted, “and I think in space it’s going to be even more hard work. So you’ve got to give people freedom of movement, freedom of information—it’s really no different from the Earth, it’s just more expanded and more vigorous of what we need to do on the Earth to maintain freedom.”

If he were to recommend to the first Martians what documents they should take with them to help design their new society, Cockell unhesitatingly offered “The U.S. Constitution, Bill of Rights and the Declaration of Independence,” adding that the latter “is not just about independence; it’s also about the ideals of free governance.” Here the analogue is fitting, given that on a planet in which nearly every square foot of land (and much of the sea) is already under some form of governmental legislation, there are few opportunities to start anew, so the U.S. experiment in governance is one well worth emulating. “One of the moments of genius of the founding fathers…was they recognized that human beings can never be made perfect. Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. You can’t make people perfect. You must take a cynical view and assume they are very imperfect and create the checks and balances to hold those slightly more negative aspects of humans in check.” Among the new ideas Cockell and his colleagues came up with is modularity, literally incorporating liberty into architecture:

You could modularize a settlement so that there’s lots of oxygen production machines, lots of food production machines, such that the failure of any one of them does not threaten the whole settlement. [Decentralization] allows people to do their own thing. The disasters happen when you try to artificially construct societies that are wholly controlled from the center or where there’s no organization and you create an anarchic society. The best forms of society have always been ones that are flexible, and modify themselves over time as fashions and ideas change, and that’s why, I think, Western democracies are reasonably successful at keeping people happy to the maximum extent you can try and do that. And I think in space there is going to be nothing different there.

Robert Zubrin, aerospace engineer, President of the Mars Society, author of The Case for Mars, The Case for Space, and Entering Space, told me when I queried him on this matter, began “I’m not going to specify a government for Mars. There will be groups of people that go to Mars and they’ll have different ideas on what the best government should be and what form of government will maximize human potential and opportunity. In fact, I think this will be a major driver for the colonization of Mars—there will be groups of people who have novel ideas in these respects and will not be popular and they’ll need a place to go where they can give these ideas a spin.”

Invoking Darwin’s idea of natural selection, Zubin went on to suggest that those with governance ideas that work will succeed and those that don’t, won’t. This, he suggests, is not unlike what happened with the founding of the United States. The liberal ideas from the Enlightenment that the founders evoked were not unknown in Europe, but the long-established power structures prevented them from flourishing there. “Mars won’t be utopia,” Zubrin added, invoking instead the U.S. founders description of America as a grand experiment in governance. “It will be a lab. It will be a place where experiments are done.” But what if a Martian tyrant turns off the air of the people in order to control them, I inquire? “Specialization leads to empowerment,” Zubrin countered, explaining that autocrats could control peasants in medieval Europe because they were living in such a simple society that tyrants could do away with them if they didn’t obey. On Mars, everyone will be critical to everyone else’s survival, so “extraterrestrial tyranny is impossible.”

There are, as well, a variety of social experiments in setting up new societies here on Earth that differ from nations and states from which we may glean insights into extraterrestrial governance. These natural experiments in living are deeply explored by the evolutionary sociologist Nicholas Christakis in his 2019 book Blueprint: The Evolutionary Origins of a Good Society. Let’s look at a few examples and see what light might be shown on what the first space-faring civilizational founders should do, starting with Christakis’s list of eight social characteristics that are at the core of all good societies:

The capacity to have and recognize individual identity.

Love for partners and offspring.

Friendship.

Social networks.

Cooperation.

Preference for one’s own group (“in-group bias”).

Mild hierarchy (relative egalitarianism).

Social learning and teaching.

Whatever the right balance of these characteristics will be for the first space colonists remains to be seen, but the overall balance to be sought is between individualism and group living—individual autonomy balanced with commitment to the community.

These rules apply to intentional communities, but Christakis considers natural experiments in the form of unintentional communities, a type of “forbidden experiment” that would never get the approval of a research IRB (Institutional Review Board). Being stranded in a remote place is one such natural experiment, and Christakis accesses a database published in an 1813 work, Remarkable Shipwrecks: A Collection of Interesting Accounts of Naval Disasters with Many Particulars of the Extraordinary Adventures and Sufferings of the Crews of Vessels Wrecked at Sea, and of Their Treatment on Distant Shores. Christakis includes a table of 24 such small-scale shipwreck societies over a 400-year span from 1500 to 1900, with initial survival colony populations ranging from 4 to 500, with a mean of 119 (2,870/24 = 119.5), but with much smaller numbers of rescued survivors, ranging from 3 to 289, with a mean of 59 (1,422/24 = 59.25), reflecting their success or failure at striking the right balance. The duration of these unplanned societies ranged from 2 months to 15 years, with a mean of 20 months (461.5/23 = 20.06; one group was rescued after 13 days so I didn’t count them).

Some of the survivors killed and ate each other (murder and cannibalism), while others survived and flourished and were eventually rescued. What made the difference? “The groups that typically fared best were those that had good leadership in the form of mild hierarchy (without any brutality), friendships among the survivors, and evidence of cooperation and altruism,” Christakis concludes. The successful shipwreck societies shared food equitably, took care of the sick and injured survivors, and worked together digging wells, burying the dead, building fires, and building escape boats. There was little hierarchy—for example, while on board their ships officers and enlisted men were separated, but on land successful castaways integrated everyone in a cooperative, egalitarian, and more horizontal structure, putting aside prior hierarchical class differences in the interest of survival. Camaraderie emerged and friendships across such barriers were formed.

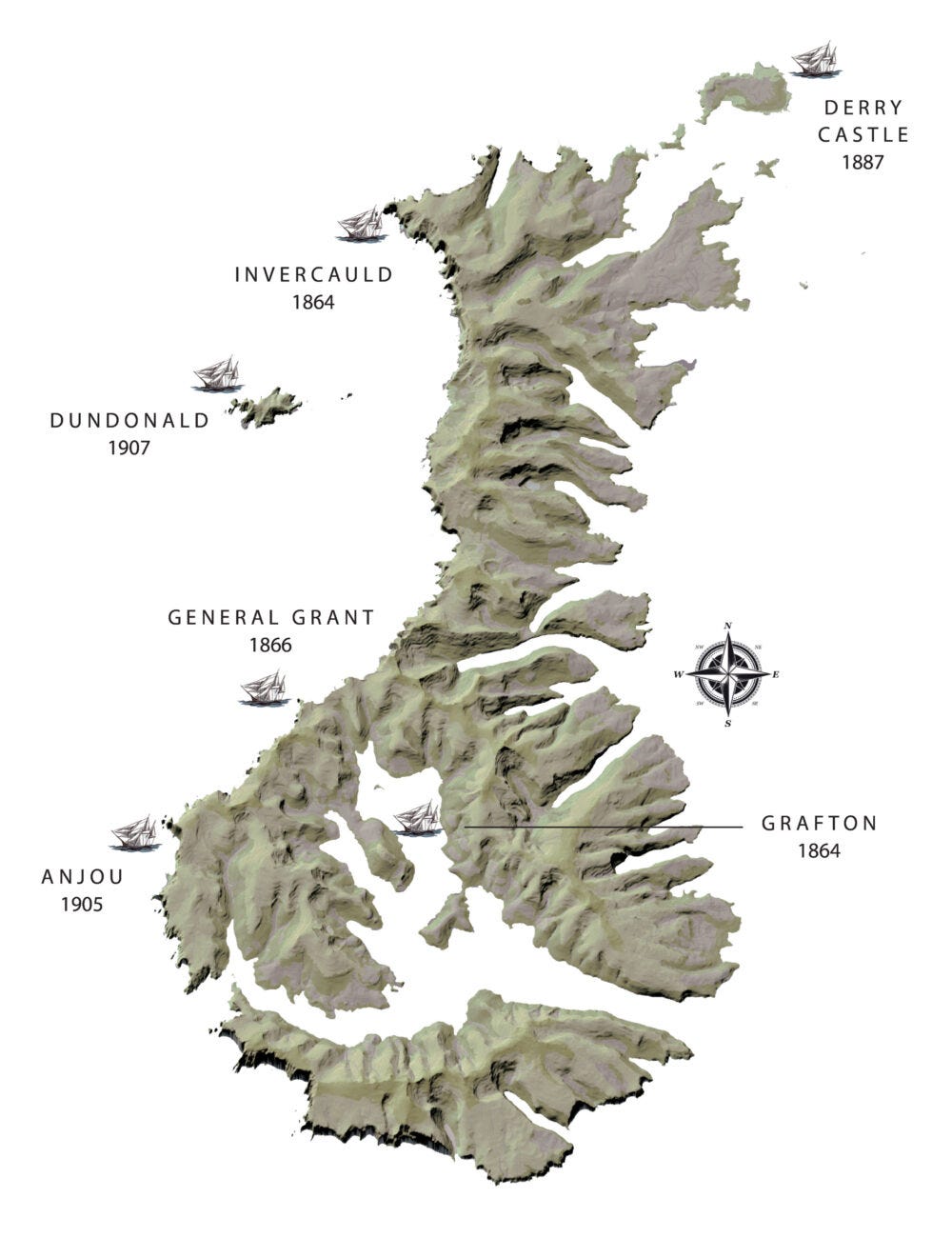

The closest thing to a control experiment in this category was when two ships (the Invercauld and the Grafton) wrecked on the same island (Auckland) at the same time in 1864. The island is 26-miles long and 16-miles wide and lies 290 miles south of New Zealand (see map below), truly isolated. The two surviving groups were unaware of one another, and their outcomes were starkly different. For the Invercauld, 19 out of 25 crew members made it to the island but only 3 survived when rescued a year later, whereas all five of the Grafton crew made it to land and all 5 were rescued two years later.

As Christakis explains:

The differential survival of the two groups may be ascribed to differences in initial salvage and differences in leadership, but it was also due to differences in social arrangements. Among the Invercauld crews, there was an “every man for himself” attitude, whereas the men of the Grafton were cooperators. They shared food equitably, worked together toward common goals (like repairing the dinghy), voted democratically for a leader who could be replaced by a new vote, dedicated themselves to their mutual survival, and treated one another as equals.

Take note future space colonists.

Illustration of the Loss of the Grafton on Auckland Island, 1863 (left).The last of the Grafton castaways are rescued (right). Source: Wrecked on a Reef, Raynal, 1874.

The long-term historical trend in moral progress that I document in The Moral Arc points to the fact that some form of governance is absolutely necessary to attenuate our inner demons and to accentuate our better angels. But let’s not restrict ourselves by the categorical thinking such labels as nation-state or city-state impose, as these are just ways of describing a linear process of governing groups of people of varying sizes. Such systems have taken many forms over the centuries, but in time they have narrowed their scope to include most of the following characteristics that the majority of Western peoples enjoy today (call them the Justice and Freedom Dozen):

A liberal democracy in which the franchise is granted to all adult citizens.

The rule of law defined by a constitution that is subject to change only under extraordinary circumstances and by judicial proceedings.

A viable legislative system for establishing fair and just laws that apply equally and fairly to all citizens regardless of race, religion, gender, or sexual orientation.

An effective judicial system for the equitable enforcement of those fair and just laws that employs both retributive and restorative justice.

Protection of civil rights and civil liberties for all citizens regardless of race, religion, gender, or sexual orientation.

A potent police for protection from attacks by other people within the state.

A robust military for protection of our liberties from attacks by other states.

Property rights and the freedom to trade with other citizens and companies both domestic and foreign.

Economic stability through a secure and trustworthy banking and monetary system.

A reliable infrastructure and the freedom to travel and move.

Freedom of speech, the press, and association.

Mass education, critical thinking, scientific reasoning, and knowledge available and accessible for all.

Martian political, economic, and legal institutions will likely vary from Earthly ones according to the most basic needs of the first colonists, but any such variation will be necessarily bounded by human nature. Perhaps SpaceX or NASA will create a division of Social Engineers—a team of legal scholars, political scientists, economists, social psychologists, and conflict resolution scholars—and they’ll come up with a wholly different system of governance. Who knows what these space seeds might sprout in the coming centuries and millennia? Whatever we do, we better get it right, because as the political commentator Charles Krauthammer wrote in his aptly titled book Things that Matter:

Politics, the crooked timber of our communal lives, dominates everything because, in the end, everything—high and low and, most especially, high—lives or dies by politics. You can have the most advanced and efflorescent of cultures. Get your politics wrong, however, and everything stands to be swept away.

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, Executive Director of the Skeptics Society, and the host of The Michael Shermer Show. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc,, Heavens on Earth, and Giving the Devil His Due. His latest book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational. His next book is: Truth: What it is, How to Find it, Why it Matters, to be published in 2025. Order The Institutions of Extraterrestrial Liberty by clicking on the link or image below.

Two observations:

1. The analysis of dyadic complexity is oversimplified in a way that hides an important detail. For me and 20 others, there are about 200 possible dyads. But when it comes to 2,000 others, there are probably no more than 10,000 possible dyads due to time and effort and lack of interest. The problem is that the dyadic graphs are themselves objects with their own pair dyads, but this new level has emergent properties that do not exist on the lower level.

2. Instead of looking back at foundational documents, we should focus on the method of writing the foundational documents. I advocate a triadic approach. Based on my experience with Nuclear Power Plant operating procedures, there are three parts: the theory, the procedure and the validation metric. This is also true for software documentation: requirements/design/test. For example, the US Constitution contains only the procedures (the articles and amendments). Typically, people go back to documents like the Federalist Papers, which you quote. This theoretical justification should have been written into the Constitution alongside the procedures. The third part - the validation metric - is completely missing from the Constitution and even our current government. For example, the section on Presidential elections, besides having the theoretical justification for the way it is implemented, should also have a way of judging if the election was free and fair, whether it met the theoretical desiderata and a time-based analysis of long-term outcome that determines whether the outcome was a sound one. If the validation fails (such as unintended consequences), then there could be one of three reasons: the theory is wrong and needs to be updated, leading to new procedures and new validation criteria; the procedure is wrong and does not meet the theoretical needs; or the validation metric is wrong - it does not measure how theory and practice mesh. I am unaware of any government document anywhere that is written in this style.

You didn't mention selection? The type of person who would go to Mars may be more likely to fit the survival framework. The vulnerable narcissists and power-trippers might choose to stay on earth, where they seem to run things. Martian society might be a different mix of people as a result.