Free Speech and Theater Fires

Why Tim Walz, along with everyone who mindlessly repeats the line that you can't shout "fire" in a theater, are misinformed and wrong.

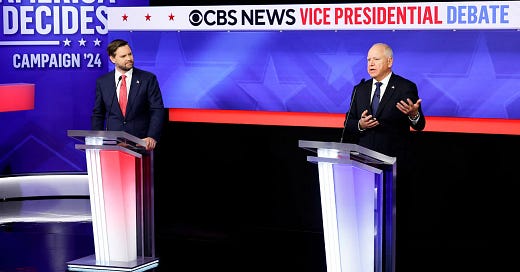

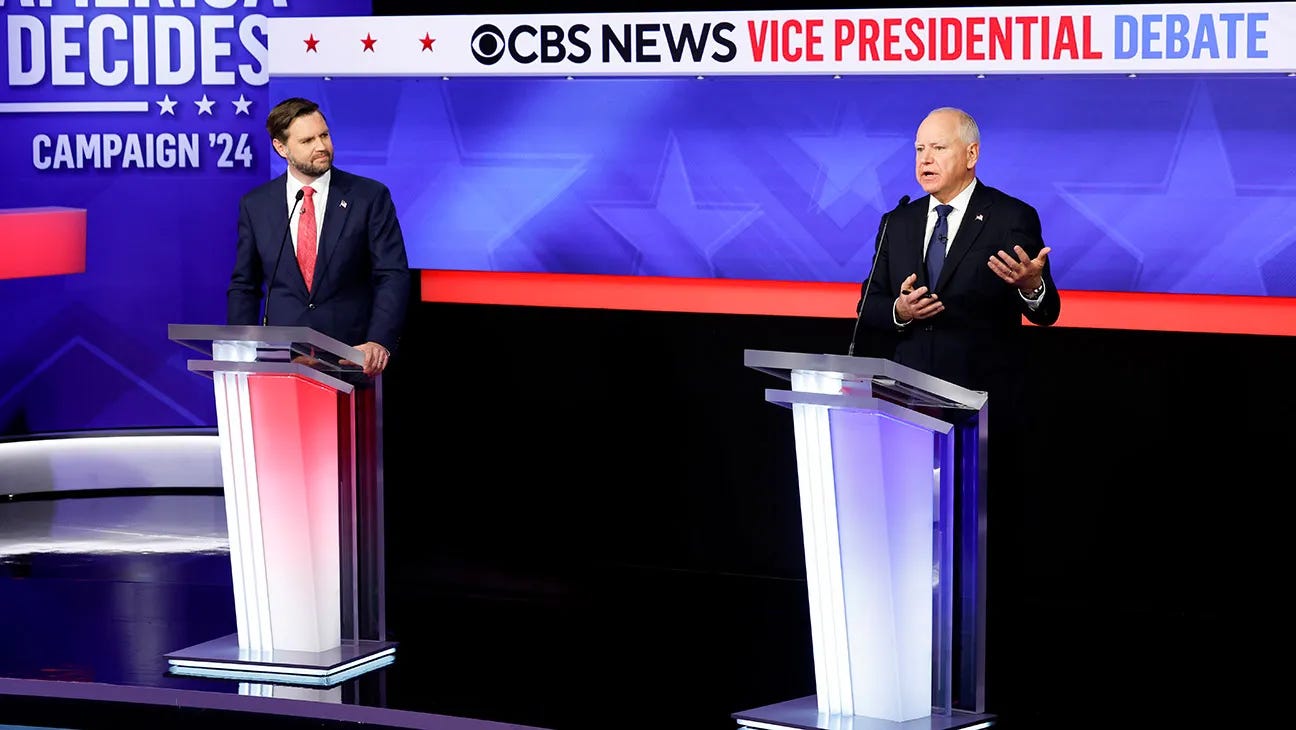

In his Vice Presidential debate with Ohio Senator J.D. Vance, in their discussion about the January 6, 2021 riot at the U.S. Capitol, Minnesota Governor Tim Walz asserted:

“You can’t yell fire in a crowded theater. That’s the test, that’s the Supreme Court test.”

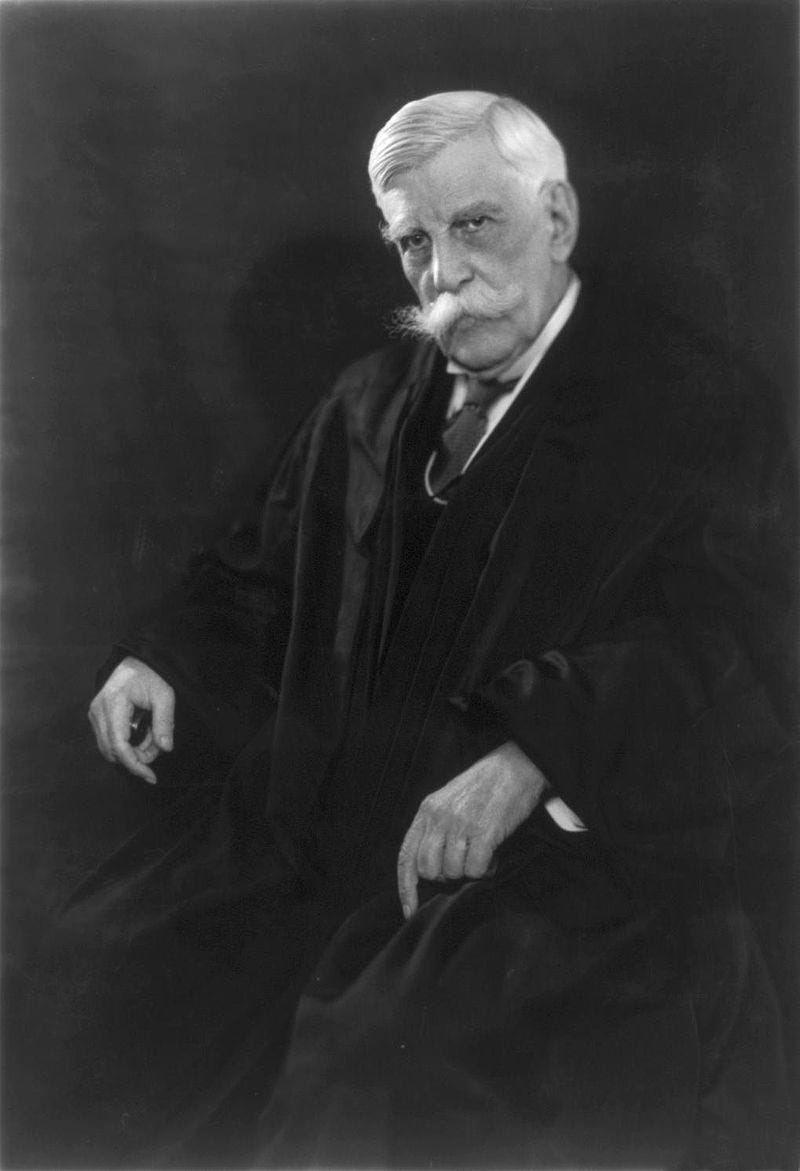

Almost no one who memetically repeats this line knows its context, why it is wrong, and why the originator of the theater case example—SCOTUS Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.—changed his mind when he realized that the decision became an overwrought excuse to silence anyone with whom one disagrees.

In Giving the Devil His Due, my 2020 book defending free speech, open inquiry, and scientific humanism, I reviewed the case in detail because it is so commonly misunderstood. To wit, Justice Holmes’ unanimous opinion in the 1919 case of Schenck v. United States included these now famous and oft-quoted lines:

The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic. ... The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree.

What were the falsely shouted utterances that Justice Holmes’ feared constituted a clear and present danger? They were 15,000 fliers distributed to draft-age men during the First World War that encouraged them to “Assert your rights,” “Do not submit to intimidation,” and “If you do not assert and support your rights, you are helping to deny or disparage rights which it is the solemn duty of all citizens and residents of the United States to retain.” The right to what?

Freedom.

Freedom from what?

Slavery.

Slavery?

According to the distributors of the fliers—Charles Schenck and Elizabeth Baer, members of the Executive Committee of the Socialist Party in Philadelphia—military conscription constituted involuntary servitude, which is strictly prohibited by the Thirteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. “When you conscript a man and compel him to go abroad to fight against his will, you violate the most sacred right of personal liberty, and substitute for it what Daniel Webster called ‘despotism in its worst form’,” they wrote in their broadside, elaborating:

A conscript is little better than a convict. He is deprived of his liberty and of his right to think and act as a free man. A conscripted citizen is forced to surrender his right as a citizen and become a subject. He is forced into involuntary servitude. He is deprived of the protection given him by the Constitution of the United States. He is deprived of all freedom of conscience in being forced to kill against his will.

For this treasonous act of voicing their opposition to the draft (and U.S. involvement in a largely European war), Schenck and Baer were convicted of violating Section 3 of the Espionage Act of 1917, passed shortly after U.S. entry into the Great War in order to prohibit interference with government recruitment into the armed services, and to prevent insubordination in the military and/or support for enemies of the United States during wartime.

It sounds like an antiquated law applicable to a darker time in American history, employed as it was to silence such socialists as the newspaper editor Victor Berger, the labor leader and Socialist Party of America Presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs, anarchists Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, communists Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, and Pentagon Papers revealer Daniel Ellsberg. But, in fact, the Act is still used today as a cudgel against such whistleblowers as diplomatic cable leaker Chelsea Manning and NSA contractor Edward Snowden, still on the lam in Moscow for his Wikileaks revelations about spying (and other questionable activities) on both American citizens and foreign actors (including German Chancellor Angela Merkel) by the United States government.

Tellingly, as mission creep set in and “clear and present danger” expanded to include speech unrelated to military operations or combatting foreign enemies, Holmes dissented in other cases, reverting to a position of absolute protection for nearly all speech short of that intended to cause criminal harm, concluding that the “marketplace of ideas” of open discussion, debate, and disputation was the best test of their verisimilitude.

Interestingly, in an earlier and similar case that came before the court involving anti-draft protesters convicted for obstructing recruitment and enlistment services that the SCOTUS voted to affirm, Holmes dissented thusly:

Real obstructions of the law, giving real aid and comfort to the enemy, I should have been glad to see punished more summarily and severely than they sometimes were. But I think that our intention to put out all our powers in aid of success in war should not hurry us into intolerance of opinions and speech that could not be imagined to do harm, although opposed to our own. It is better for those who have unquestioned and almost unlimited power in their hands to err on the side of freedom.

Err on the side of freedom.

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, Executive Director of the Skeptics Society, and the host of The Michael Shermer Show. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc,, Heavens on Earth, and Giving the Devil His Due. His latest book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational. His next book is: Truth: What it is, How to Find it, Why it Matters, to be published in 2025.

The context of speech is crucial when determining whether it is protected by the First Amendment.

The "shouting fire in a crowded theater" analogy was used to illustrate this point. While it is generally protected to say "fire" in a crowded theater, it is not protected to say "fire" in a crowded theater with the intent of causing a panic. In other words, the context of the speech can make all the difference.

Similarly, the events of January 6, 2021 were not merely free speech. They were an insurrection, an attempt to overthrow the legitimate government of the United States. The people who participated in the insurrection were not exercising their right to free speech; they were committing a crime.

It is important to remember that the First Amendment does not protect all speech. It does not protect speech that is intended to incite violence or to overthrow the government. It also does not protect speech that is defamatory or obscene.

"still on the lamb in Moscow"

I would feel sheepish making that mistake... ;-)

FYI: It's 'on the lam'