How To Think About the Resurrection

Was Jesus really raised from the dead?

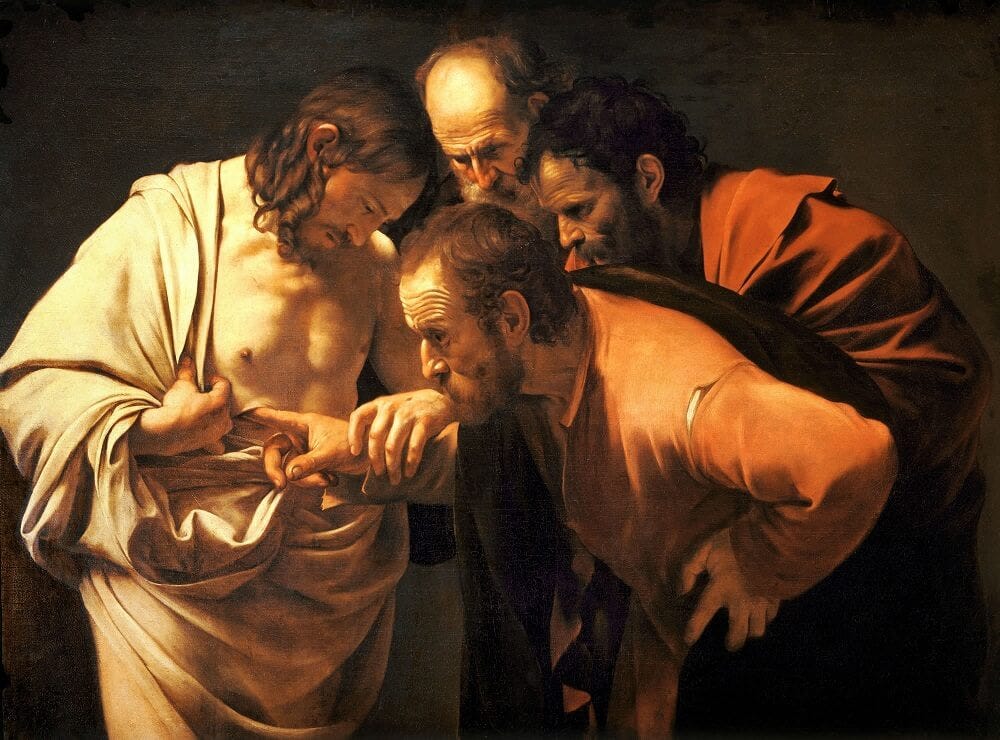

On this Easter 2023, let us reflect on what is arguably the greatest miracle ever performed—the raising from the dead the body, life, and person known as Jesus of Nazareth. This miracle is believed by over 2.6 billion people—a third of humanity—to be true. Is it? Was Jesus really raised from the dead? Like the apostle Thomas, I have my doubts.

First, let me note that what we’re talking about here is the claim of an empirical objective truth: that there was a man named Jesus who was put to death by crucifixion and resurrected from the dead three days later, after which he ascended to heaven. The claim under consideration here is not just a literary truth, as when U.S. Presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, a deeply religious man, in his 1896 Democratic National Convention “Cross of Gold” speech, famously pronounced “we shall answer their demands for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” Nor is this claim merely a metaphorical or mythic truth, in which readers might be inspired to “bear your own cross” or admonished not to be “crucified” by your enemies, or warned not to “resurrect” bad habits, or encouraged to become “born again” through good habits, or to forgive those who sin against us as God forgives us for our sins through the death and resurrection of his only begotten son.

Nor does this have to do with the proposition that Jesus died for our sins, which is a faith-based truth claim with no purchase on valid knowledge. Such a central tenet of the Christian faith cannot be tested or falsified. It cannot be confirmed or disconfirmed. It can only be believed or disbelieved based on faith or the lack thereof. It is in the realm of religious truths, which are different from empirical truths. Such literary, mythic, and metaphorical truths play a central role in human culture and learning through the arts, literature, and religion, but that is not how most Christians think about the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus. They believe it is literally true. I know because I have debated a number of theologians and biblical scholars on this and related topics, and when they speak of the death and resurrection of Jesus they are not channeling Joseph Campbell’s “power of myth”. They accept the apostle Paul’s challenge (in 1 Cor. 15:13-19) that: “if there is no resurrection of the dead, then Christ is not risen. And if Christ is not risen, then our preaching is empty and your faith is also empty. For if the dead do not rise, then Christ is not risen. And if Christ is not risen, your faith is futile; you are still in your sins!”

The proposition that Jesus was crucified may be true by historical validation, inasmuch as a man named Jesus of Nazareth probably existed, the Romans routinely crucified people for even petty crimes (recall that the two other people crucified with Jesus that day were impenitent thieves), and most biblical scholars—even those who are atheists, such as the renowned University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Religious Studies professor Bart Ehrman—assent to this fact. In between these propositions is Jesus’s resurrection, which is not impossible but would be a miracle if it were true. How big a miracle would it be?

Let’s begin our analysis with the Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume, and Section XII of his book Philosophical Essays Concerning the Human Understanding, titled “Of the Academical or Sceptical Philosophy.” Here Hume distinguishes between “antecedent skepticism”, such as Descartes’s method of doubting everything, that has no “antecedent” infallible criterion for belief, which means we can’t really know anything; and “consequent skepticism,” the method Hume employed that recognizes the “consequences” of our fallible senses but corrects them through reason so that we can have confidence that we can know some things with confidence. As he advised: “A wise man proportions his belief to the evidence.”

Let’s call this the principle of proportionality, better known as the ECREE principle—extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. Carl Sagan made famous the principle, but he was quoting the lesser-known sociologist of science Marcello Truzzi (thereby confirming the observation that pithy and oft-quoted statements migrate up to the most famous person who said them). Let’s see how this principle cashes out for a miracle like the resurrection and whether or not we should believe it.

How extraordinary a claim is the resurrection? Let’s put some numbers on it. Demographers estimate that throughout all of human history approximately 100 billion people have lived before the 8 billion people alive today. Not one of those 100 billion people has died and returned from the dead, except maybe one—Jesus of Nazareth. So the claim that one person out of those 100 billion people who died came back from the dead would be extraordinary indeed. How extraordinary? 100 billion to 1. That is about as extraordinary a claim as one will ever find. Is the evidence proportional to the conviction? No. Not even close.

According to the University of Wisconsin-Madison philosopher Larry Shapiro in his 2016 book The Miracle Myth, “evidence for the resurrection is nowhere near as complete or convincing as the evidence on which historians rely to justify belief in other historical events such as the destruction of Pompeii.” Because miracles are far less probable than ordinary historical occurrences like volcanic eruptions, “the evidence necessary to justify beliefs about them must be many times better than that which would justify our beliefs in run-of-the-mill historical events.” But, says Shapiro, it isn’t. In fact, it’s not even as good as ordinary historical events.

What about the eyewitnesses? Maybe, Shapiro suggests, they “were superstitious or credulous” and saw what they wanted to see. “Maybe they reported only feeling Jesus ‘in spirit,’ and over the decades their testimony was altered to suggest that they saw Jesus in the flesh. Maybe accounts of the resurrection never appeared in the original gospels and were added in later centuries. Any of these explanations for the gospel descriptions of Jesus’s resurrection are far more likely than the possibility that Jesus actually returned to life after being dead for three days.”

The principle of proportionally also means we should prefer the more probable explanation over the less, which these alternatives surely are. And this is a splendid example of Bayesian reasoning, in which the priors of non-Christians is low for their credence that the resurrection really happened, and to date no new evidence has come forth to change those priors, and so our credence in the verisimilitude of the resurrection remains low. Here’s a model example of Bayesian reasoning from the aforementioned biblical scholar and historian Bart Ehrman in his book Jesus, Interrupted:

Our very first reference to Jesus’ tomb being empty is in the Gospel of Mark, written forty years later by someone living in a different country who had heard it was empty. How would he know? Anyhow, suppose that it was empty. How did it get that way? Suppose…that Jesus was buried by Joseph of Arimathea in Joseph’s own family tomb, and then a couple of Jesus’ followers, not among the twelve, decided that night to move the body somewhere more appropriate. ... But a couple of Roman legionnaires are passing by, and catch these followers carrying the shrouded corpse through the streets. They suspect foul play and confront the followers, who pull their swords as the disciples did in Gethsemane. The soldiers, expert in swordplay, kill them on the spot. They now have three bodies, and no idea where the first one came from. Not knowing what to do with them, they commandeer a cart and take the corpses out to Gehenna, outside town, and dump them. Within three or four days the bodies have deteriorated beyond recognition. Jesus' original tomb is empty, and no one seems to know why.

Is this scenario likely? Not at all. Am I proposing this is what really happened? Absolutely not. Is it more probable that something like this happened than that a miracle happened and Jesus left the tomb to ascend to heaven? Absolutely! From a purely historical point of view, a highly unlikely event is far more probable than a virtually impossible one.

The number of gospel inconsistencies and incompatibilities doesn’t help the credence of the resurrection. For example, the gospels do not agree on: how many women came to the tomb (1, 2, or 3 plus “others”); when they came (“while it was still dark” or “just after sunrise”); why they came (“to look at the tomb” or “to anoint the body with spices”); who they saw (one angel, two angels, a man dressed in white, or Jesus himself); what was said, who said what, who else came (Peter, or both Peter and John); who saw the resurrected Jesus first (Peter or Mary Magdalene); or what they did as they left the tomb (“they said nothing to anyone” or “they ran to tell his disciples”).

Matthew seems to imply the stone was rolled away in the presence of the women who came to the tomb, while Mark, Luke, and John say the women arrived to discover the stone had already been rolled away. Matthew and Mark have the resurrected Jesus on his way to Galilee by the time the women arrive at the tomb, while Luke and John have the risen Messiah in Jerusalem on the night of first Easter Sunday. The Q document, thought to be the source for Matthew, does not even mention the resurrection. The Gospel of Thomas, discovered near Nag Hammadi, Egypt, in December 1945 and dated to the early 2nd century CE, also fails to mention the resurrection. The earliest reliable written testimony of the resurrection of Jesus is by Paul and the anonymous author of Mark’s Gospel. It is important to note, in the context of the propensity of human memory to forget, conflate, confabulate, edit, redact, and falsify events that happened in the past, that the earliest Gospel of Mark was circa 66-70 CE, many decades after the events in question, with the rest of the gospels written even later.

So the extraordinary resurrection miracle claim hangs on just two early testimonies, from two ancient authors, neither of whom actually saw Jesus rise up from the dead, and neither of whom touched him, or sat down with him for a face to face conversation. We have nothing written by the Romans—or the Jews for that matter!—about Jesus, the content of his preaching, why he was killed, or what they thought about claims that he had been resurrected. You would think some Roman would have exclaimed “Et tu Again, Jesus?” or some Jew would have snapped “Oy Vey!” And the accounts from Josephus, Pliny the Elder, and Tacitus that Christians cite in evidentiary support, were from the 2nd century, and they reference Christ the Messiah, not Jesus, and they too don’t mention the resurrection.

What’s more, in his book The Case Against Miracles, the biblical scholar John W. Loftus notes that “we have no independent corroboration of the Star of Bethlehem at the birth of Jesus, or that the veil of the temple was torn in two at Jesus’ death (Mark 15:38), nor that darkness came ‘over the whole land’ from noon until three in the afternoon (Mark 15:33), or that ‘the sun stopped shining’ (Luke 23:45), nor that there was an earthquake at his death (Matt. 27:51, 54), or another ‘violent’ one the day he arose from the grave (Matt. 28:2).” Could such notable events as these really have occurred without any corroborating evidence? Surely some Roman scribe would have made a note about a three-hour midday eclipse of the sun, not to mention the other miracles. No such extra-biblical evidence exists. Here, the absence of evidence is evidence of absence.

What about the 500 people the apostle Paul says saw the risen Jesus? People often interrupt this to mean that there were 500 independent eyewitness accounts of seeing Jesus after the crucifixion. Not so. We have one account saying there were 500 witnesses, by an evangelist who was highly motivated to write a history in support of his new-found religion—recall that Paul was previously Saul, who converted to Christianity from Judaism after his vision on the road to Damascus.

To that end, a challenge to the resurrection miracle that I often employ is that Jews do not accept it as real, neither in Jesus’ time nor in ours. Think about that: Jews believe in the same God as Christians. They accept the Old Testament of the Bible like Christians do. They even believe in the Messiah. They just don’t think Jesus of Nazareth was him. Jewish rabbis, scholars, philosophers, and historians all know the arguments for the resurrection as well as Christian apologists and theologians making the arguments, and still they reject them. Why? If the arguments and evidence for the resurrection is so solid, in time the community most expert in that field would reach a consensus about it. They haven’t. Christians believe it. Jews don’t. Ben Shapiro explains why here, in our conversation on his Sunday Special show.

Finally, it is important to put the resurrection into historical context, which Bart Ehrman does when he notes that in an ancient view of the divine realm “gods could sometimes be or become humans, and humans could sometimes be or become gods.” Ehrman outlines three models of “divine men” that were common in the ancient world:

Sometimes it was understood that gods could and would come down to earth in human form to make a temporary visit for purposes of their own.

Sometimes it was understood that a person was born from the sexual union of a god and a mortal; thus, that the person was, in some sense, part divine and part human.

Sometimes it was understood that a human was elevated by the gods to their realm, usually after death, and at that point divinized, made into a god.

As Ehrman documents, there are many stories in ancient myths about gods temporarily assuming human form to meet, speak, and interact with humans, and that these stories in many ways are similar to later Christian beliefs about Christ being a preexistent divine being who came to earth as a human, only later to return to the heavenly realm.

Perhaps this is why Jesus was silent when Pilate asked him (John 18:38) “What is truth?”

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the host of The Michael Shermer Show, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His new book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational.

Great article until I saw the video w Shapiro.

It should also be noted that stories of resurrections were common in the ancient world. The Egyptians and the Greeks had many resurrection stories. Even the Jews, in Book of Enoch, 2 Baruch and 2 Esdra espouse beliefs in them. Point being that these beliefs were widely known in the Middle East well before Jesus woke up from the dead and could have perhaps influenced the Easter myth.