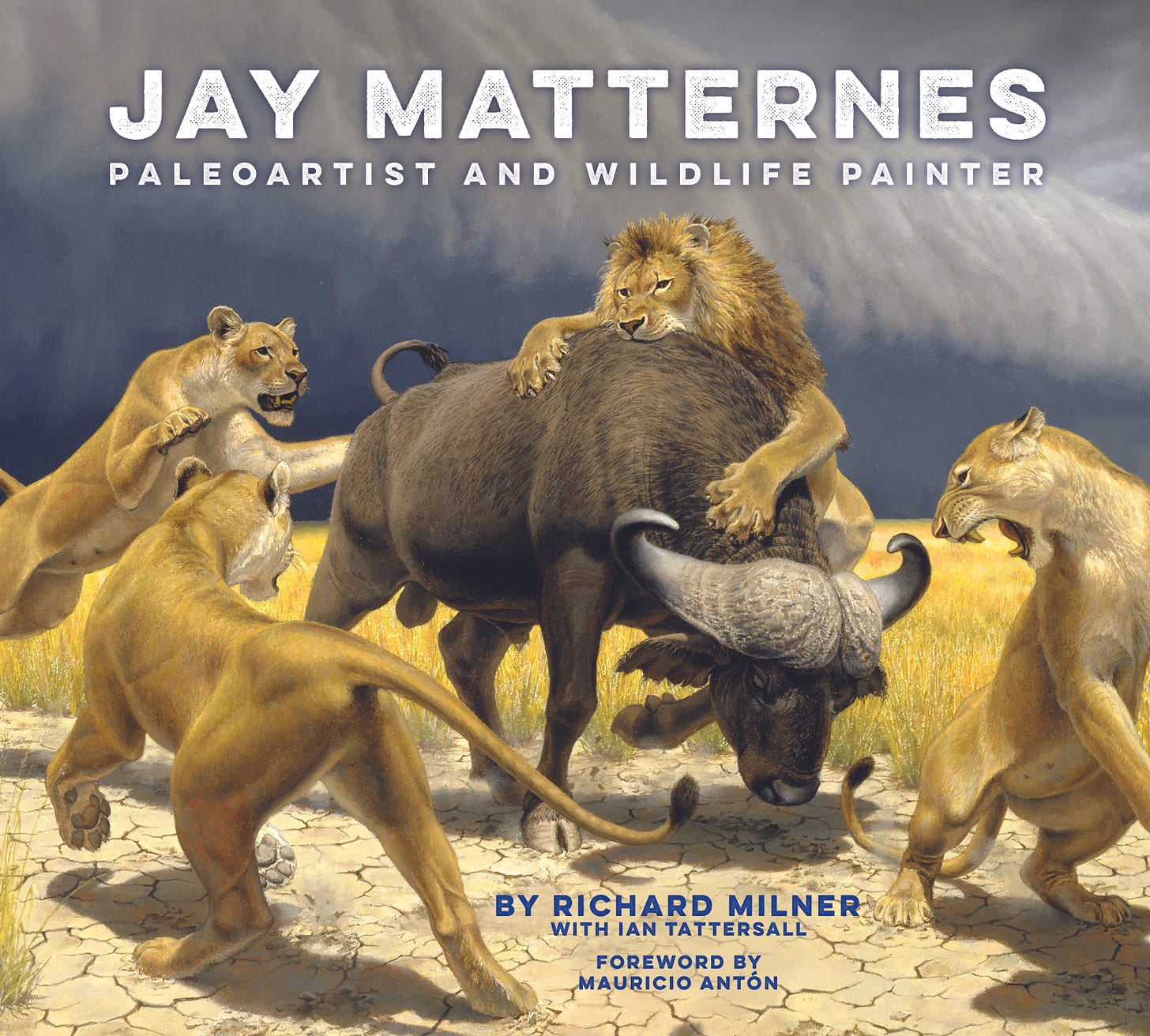

Illustrating the Past

Donald Prothero reviews historian of science Richard Milner's new book on paleoartist and wildlife painter Jay Matternes, who brought the past to life in striking paintings

A Review of Jay Matternes: Paleoartist and Wildlife Painter, by Richard Milner, with Ian Tattersall, and with a Foreword by Mauricio Anton, 196 pages, Abbeville Press, New York and London, 2024.

Reviewed by Donald Prothero

Richard Milner is an anthropologist and historian of science whose books include Charles R. Knight: The Artist Who Saw through Time and Darwin’s Universe: Evolution from A to Z. An Associate at the American Museum of Natural History, Milner has appeared on the History Channel, Discovery, and NPR, and has been profiled in the New York Times and Time Out New York.

Ian Tattersall is Curator Emeritus at the American Museum of Natural History and a leading paleoanthropologist.

Mauricio Anton is a celebrated paleoartist based in Spain.

Donald Prothero is a geologist, paleontologist, and author who specializes in mammalian paleontology and magnetostratigraphy, a technique to date rock layers of the Cenozoic era and its use to date the climate changes which occurred 30–40 million years ago. He is the author or editor of more than 30 books and over 300 scientific papers, including at least 5 geology textbooks. His books include: Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why it Matters, Vertebrate Evolution: From Origins to Dinosaurs and Beyond, The Story of Earth's Climate in 25 Discoveries: How Scientists Found the Connections Between Climate and Life, Catastrophes!: Earthquakes, Tsunamis, Tornadoes, and Other Earth-Shattering Disasters, Abominable Science!: Origins of the Yeti, Nessie, and Other Famous Cryptids, and UFOs, Chemtrails, and Aliens: What Science Says.

Creation of Cave Bison Sculptures, Tuc Daudoubert, Ariege, France, 1994.

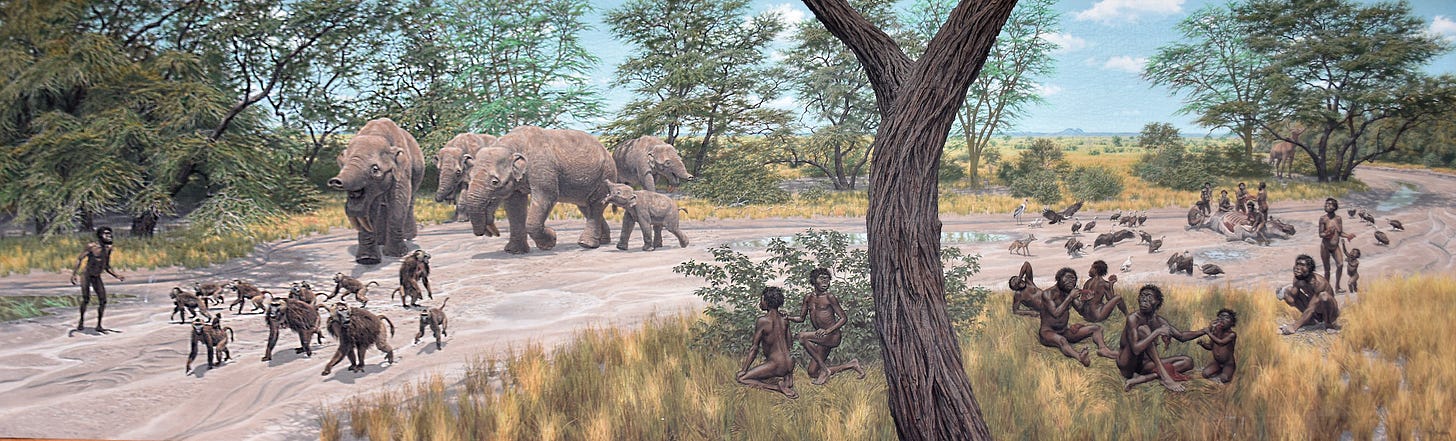

Early hominids, Oil on board, 1974.

If the legendary Charles R. Knight can be considered the “Father of Paleoart” through his pioneering work in the first third of the twentieth century (the subject of Richard Milner’s 2012 book Charles R. Knight: The Artist Who Saw Through Time), then Jay Matternes might be considered his direct successor, the most famous, respected, and influential paleoartist of the second half of the twentieth century. The general public may not know his name, but they have seen his famous paintings on the walls of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, where six huge murals of different time periods of the “Age of Mammals” were longtime mainstays.

Sioux Indian Village in 1880s. Storyteller’s circle. Oil on canvas, 2019.

Or they may have seen his images of extinct humans that graced many books and magazines of the National Geographic Society and Scientific American, as well as many other media, often without credit to the artist. Among my paleoartist friends, he is revered as the greatest of his generation, and an inspiration for their work. This is reflected in the Foreword by famous Italian paleoartist Mauricio Anton, now based in Spain, who discusses how Matternes’ work influenced his own, or the recent podcast by paleoartist Ray Troll, on which he interviewed Matternes, his greatest inspiration as a paleoartist. Happily, Jay is sharp and still going strong at age 91, so he was an active participant in these tributes. For this book, he provided all sorts of images from his treasure trove of old files for anthropologist and historian of science Richard Milner to compile and publish—and these just a sampling of his long career in paleoart and wildlife art.

Olduvai Lakeshore with Hominins 1.8 million years ago. Charcoal drawing for “Lucy’s Child,” 1989.

And what a wonderful book it is! Gorgeously printed on glossy stock in large format, all the images are still awe-inspiring as they leap off page after colorful page. Milner helped to create an archive of nearly every aspect of Matternes’ art career, from his childhood sketches to many of his early studies, to dozens of paintings of living animals, to most of the stunning reconstructions of prehistoric humans done for National Geographic magazine, as well as for books by many famous paleoanthropologists, including Louis and Richard Leakey, Don Johanson, Tim White, and many others. He was the first choice of artists when paleoanthropologists required a reconstruction of Ardipithecus in 2009, over 50 years after his career in paleoart first began.

Buffalo Jump: Plains Indians in Central Montana stampede bison over cliff. Oil on canvas, 1977.

But the book is far more than its pretty pictures. Milner interviewed Matternes extensively, and also went through his archives of correspondence with many famous scientists. Who knew that Matternes visited the legendary gorilla ethologist Dian Fossey at her camp in Rwanda several times, and became her good friend? Or that Matternes illustrated Jane Goodall’s 1967 book on her wild chimpanzees (My Friends the Wild Chimpanzees). Both Goodall and Fossey found it hard to capture many aspects of ape behavior in photographs and enlisted the talents of Matternes to paint and draw them instead. Matternes was still corresponding with Fossey when she was tragically murdered in her field station in 1985, possibly by gorilla poachers who resented her active interference in their activities.

Jane Goodall’s Chimpanzees in Rain Dance Frenzy.

We see images of how Matternes worked from bones and replicas of fossils, did extensive dissections of animals that had recently died in zoos, did lots of preliminary sketches before starting the final color paintings. and took innumerable photos of both animals and their landscapes to make his own art truly photorealistic. Each page of images also has extensive text about how the art was inspired, or what led to the details that we see in the final image, often including Matternes’ own memories of how and when that art was done.

Matternes Brings Ardi back to life.

Jay Matternes was born on a military base on Corregidor Island in the Philippines on April 14, 1933, the son of a surgeon in the U.S. Army, so spent much of his childhood as an Army brat. He lived on one military base after another, although he spent most of his adolescence in the Philadelphia area. The book relates how a 1946 visit with his father to the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Bronx Zoo changed his life forever, inspiring him with the museum’s amazing prehistoric skeletons and art images by Charles R. Knight, as well as the zoo’s impressive collection of live animals. Matternes won an art scholarship at the Carnegie Institute’s College of Fine Arts in Pittsburgh, where he developed his professional skills. He was then drafted into the Army from 1958-1960, where he was assigned to do art for government projects. Coming out of the Army, he got his first big commission to work on the Smithsonian murals. Because there has been an entire book on those Smithsonian murals (Visions of Lost Worlds: The Paleoart of Jay Matternes), those images are only briefly mentioned and sampled in this book. The rest of the volume goes over each of the different categories and styles of art he produced, from living wild animals to prehistoric humans, to Native Americans, to paintings for Federal Duck Stamps to his sketches of primates for Fossey and Goodall, and paintings for the American Museum’s Hall of Human Origins, and too many more to mention.

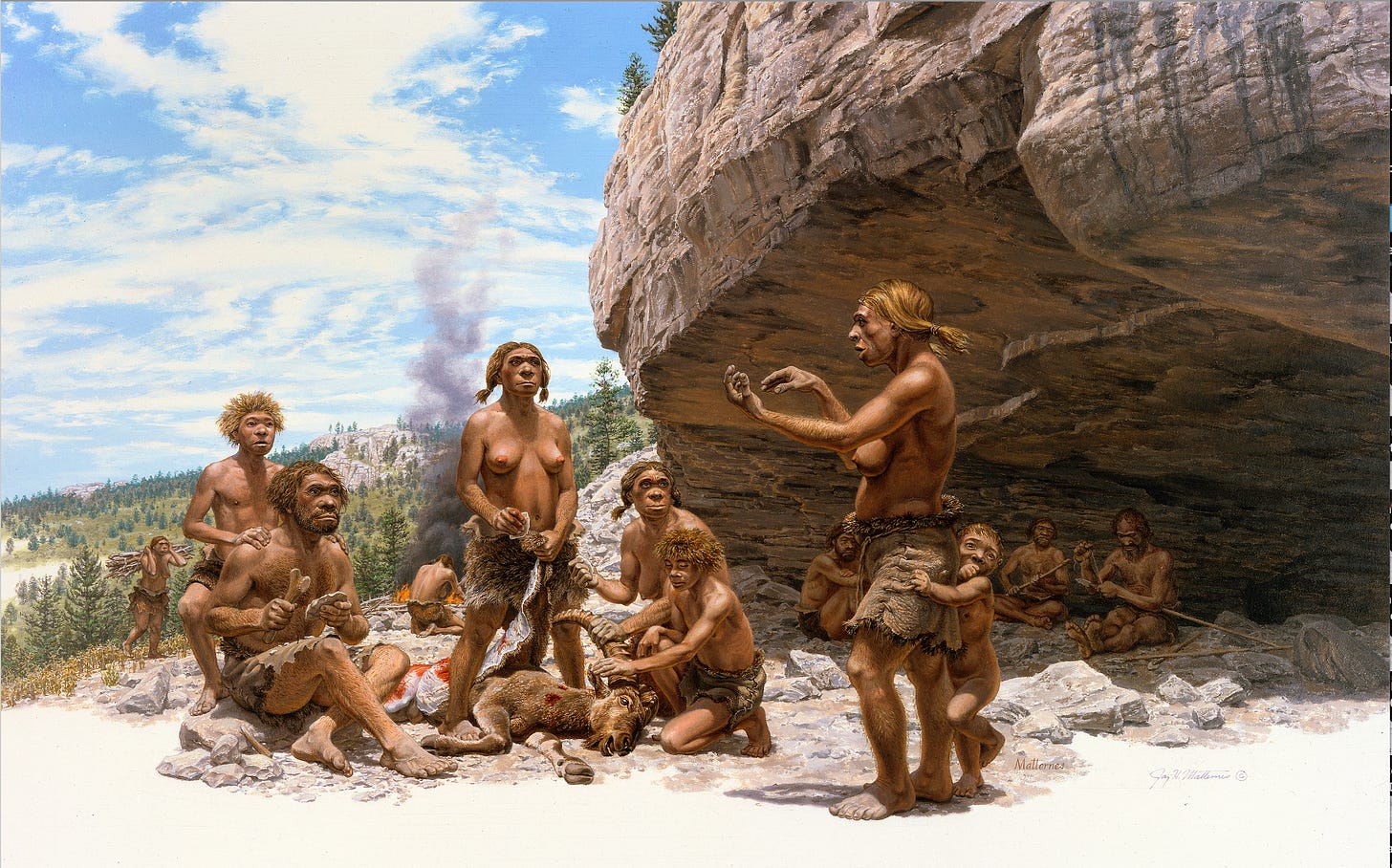

Nattering Neandertals in foothills of the French Pyrenees. Alkyd on board.

Naturally, in a book covering art and science over such a long period of time, there are some things that have changed. There are small errors associated with the names and ages and affinities of some of the prehistoric animals mentioned, or scientific terminology (such as using the term “poisonous snake” when “venomous” is what is meant). We get a sample of Matternes’ dinosaur art from the 1960s, based on the old conceptions of dinosaurs as slow, lumbering, tail-dragging reptiles. But during the “Dinosaur Renaissance” of the 1970s and 1980s, our vision of dinosaurs was transformed. Dinosaurs are now viewed as active, fast-moving, agile animals, most of whom were covered with feathers. In that respect, Matternes’ 1960s sketches give us a stark reminder of how fast science changes—and paleoart with it.

Ice Age Mammals of the Alaskan Tundra. Oil on board, 1969.

In short, it’s hard to convey how much Matternes’ work has influenced not only paleoartists, but also virtually all the paleontologists and anthropologists who have grown up with his images informing their imaginations. As a paleontologist myself who dabbled a bit in paleoart, but whose father was a professional artist tasked with drawing aircraft for Lockheed his entire career, I cannot adequately express my own admiration for Matternes’ work, and how much it influenced my career. Even though I’ve used paleoart from a variety of sources (including a few by my father), I still often re-use Matternes’ art in my own books and publications. As Mauricio Anton put it in his Foreword, Jay Matternes is still “paleoart’s Renaissance man”.

Neandertal Reindeer Hunters stalk migrating herds at France’s River Vezere. Oil on board, 2009.