In Memoriam: Bayard Brattstrom

Remembrances of one of my most influential professors and an obituary by his former students Erika M. Nowak, Marina M. Gerson, and Mary E. Shipman

I met Bayard Brattstrom in the Fall of 1976, when I matriculated at California State University, Fullerton in the M.A. program in Experimental Psychology and decided to supplement my studies there with an introductory course in evolutionary biology. Professor Meg White was one of my advisors, and her specialty was ethology and physiological psychology (as they were called then), and she highly recommended I take Bayard’s class. I didn’t know much about evolutionary theory, other than as a Christian who graduated from Pepperdine University I thought I was supposed to be a creationist. My professors at Pepperdine were not creationists, but I didn’t know that, and in my theological meanderings I stumbled across Young Earth Creationists like Duane Gish and Henry Morris. By the time I started my studies at CSUF my faith was waning and my intellectual curiosity waxing, so I was open to what this professor of herpetology had to say on the subject.

Bayard’s class met on Tuesday nights from 7:00 to 10:00 pm, during which I discovered that the evidence for evolution is undeniable and rich, and the arguments for creationism that I had been reading were duplicitous and hallow. I recall sitting there thinking “oh my God…this evolution stuff is true!” After Bayard exhausted himself with a three-hour display of erudition and entertainment, the class adjourned to the 301 Club in downtown Fullerton, a nightclub where students hung out to discuss The Big Questions, aided by adult beverages. Bayard held court there (not unlike Christopher Hitchens would do decades later when I shared conversation and libations with him at many a conference hotel bar). It was there that my mind was blown by Bayard’s expansive intellectual interests and laser-like focus on the most important questions in science and society. Much of my attention to such questions in my own research and writings today can be traced back to those Tuesday nights, like a phylogenetic tree of knowledge.

Several memories of Bayard come to mind. The Natural History Museum in Los Angeles, which we were to visit, is “Closed on Mondays!” (Presumably past students made the long drive on those closed days, turning this into a oft-repeated reminder.) Then there was Bayard’s insistence that we memorize Ernst Mayr’s definition of a species, which is still imprinted in my brain: “A species of a group of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations reproductively isolated from other such populations.” And how do species evolve? “Mutants are not monsters!” Bayard pounded into our mushy brains. His point was that notable mutations one might encounter at the county fair—two-headed cows and the like—are not the sort of mutations evolutionists are invoking. Most mutations are tiny genetic or chromosomal changes that have small effects. Some of these modest effects may provide benefits to organisms in ever-changing environments.

More still was Bayard’s insatiable curiosity and infectious enthusiasm for learning about anything and everything. (One possible exception was sports—during the baseball World Series that year I recall Bayard telling us that he thought the series was rigged to go seven games in order to sell more tickets and television commercials!) He opened my mind to an infinite world of knowledge and wonder, and for that I shall be forever in his debt.

RIP Bayard Brattstrom, a life well lived.

Bayard Holmes Brattstrom (1929–2024)

The following obituary was originally published in the Sonoran Herpetologist, Vol. 38, No. 1, 2025. Reprinted with permission from the authors.

Erika M. Nowak, Marina M. Gerson, and Mary E. Shipman

(Nowak is at the Center for Adaptable Western Landscapes, Northern Arizona University, 1395 S. Knoles Dr., Flagstaff, Arizona, USA 86011; Gerson is in the Department of Biological Sciences, California State University, Stanislaus, Turlock, CA, USA 95382. Shipman is at Casa Torcida, P.O. Box 971, Wikieup, Arizona, USA 85360. Corresponding author. E-mail: Erika.Nowak@nau.edu)

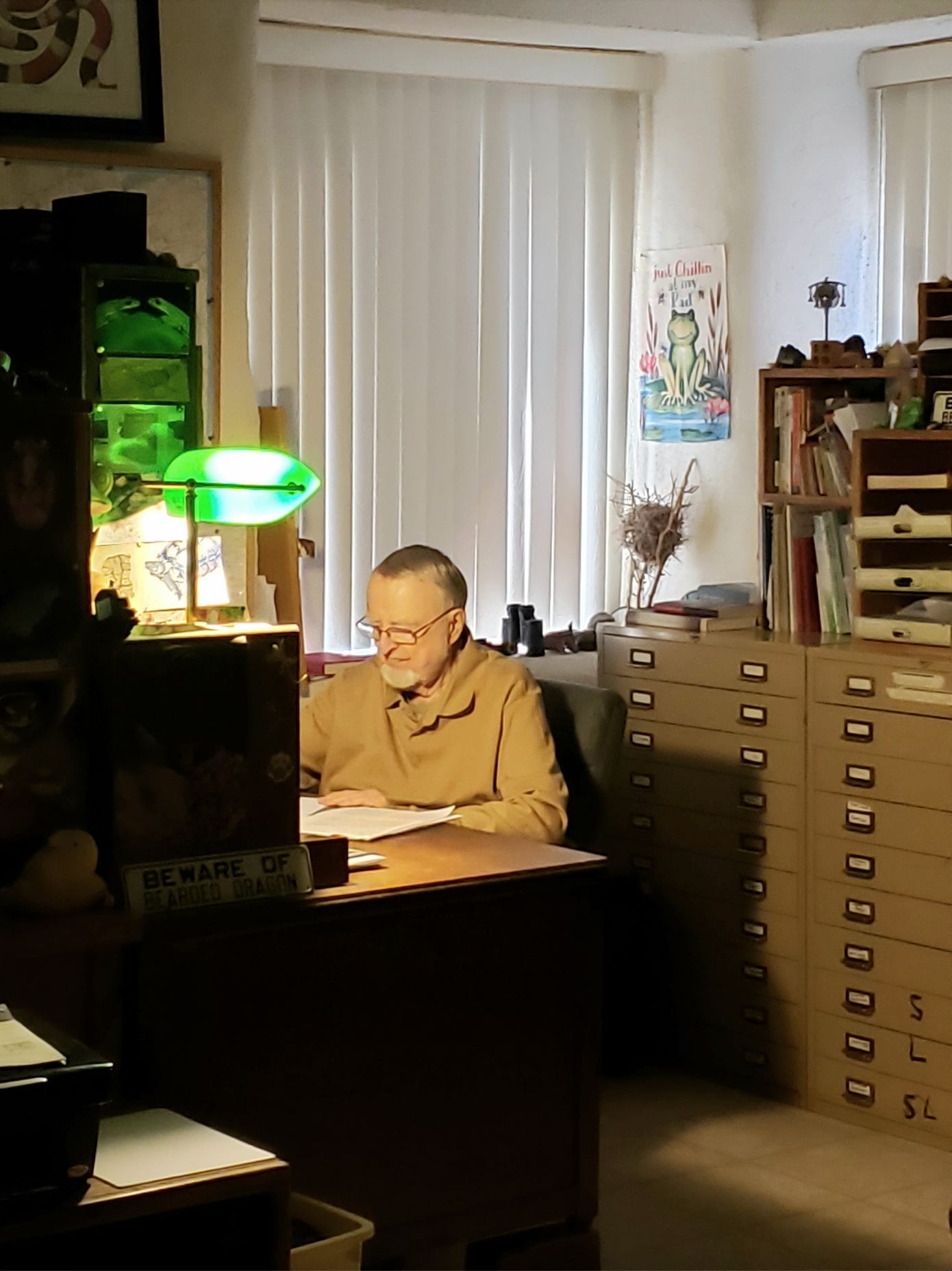

Bayard Holmes Brattstrom, Professor Emeritus of California State University, Fullerton, passed away on 13 April 2024 in Kingman, Arizona. At almost 95 years old, he was notably still living independently and publishing in an off-the-grid straw bale home on the Horned Lizard Ranch in Wikieup, Arizona (Figure 1). Here we too-briefly profile his life, based on a forthcoming extended obituary in Herpetological Review (Nowak et al. in press), a biography by Gerson (2022), and recollections of the many entertaining stories he told us.

Figure 1. Bayard Brattstrom working in his office at Horned Lizard Ranch, Wikieup, Arizona. Image by Mary Shipman.

From Chicago to Hollywood

Bayard Brattstrom was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1929 and lived there with his parents and two younger sisters, Barbara and Susan, until he was a young teenager. While Bayard’s memories had him traveling solo on streetcars at the age of six to visit Chicago’s natural history and science museums, his sister Susan Bush (pers. comm.) thinks he was likely a bit older when he had these formative adventures. In 1942, the family moved to Hollywood, California, and his mother took in boarders, including those in the movie industry, to help make ends meet. As a result of this and his high school caddy job at the Bel Air Country Club, Bayard often met famous people, including one of the Rothschilds, Phil Harris, and Bob Hope.

Probably the most important career consequence of his living in Hollywood was that the property was large enough to contain both a garage and several sheds. One of the sheds was converted to hold breeding homing pigeons, which generated income for his various hobbies, including keeping herps. After Bayard’s live snakes and lizards were banished from the garage and house following one too many eventful escapes, another shed was renovated to hold his collection. Bayard detailed these formative events and other adventures in several self-published books (e.g., Lizard Tales: People and Events in the Life of a Naturalist, Brattstrom 2018a; and Flying Fish, Pizza, Religion, and Sex: A Naturalist’s View of Life, Brattstrom 2018b).

Bayard graduated from Hollywood High School in 1947. He completed his undergraduate degree in Biology at San Diego State University (SDSU) and graduated in 1951 with honors. As he had in high school, he worked multiple odd jobs to support himself through college, including as an elevator operator, where he met Laurence M. Klauber (1883–1968). This relationship was instrumental in Bayard’s securing part-time work at the San Diego Museum of Natural History, where he eventually became the Director of Education and Assistant Curator to the Curator of Herpetology. This started his life-long passion for working with extant and paleontological museum collections. While at SDSU, Brattstrom became a member of the Herpetologists’ League and the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists (ASIH); he maintained these and many other memberships in professional organizations throughout his life. He also developed a knack for cultivating friendships and collaborations with colleagues across many disciplines and institutions, which resulted in his publishing in fields outside of herpetology. Bayard’s first publication was a natural history note about Clark’s Nutcrackers, Nucifraga columbiana (Brattstrom and Sams 1951); some later contributions were in archaeology (e.g., Brattstrom 1998a).

Academia and Service

In 1952, Bayard both started his graduate research at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and married SDSU alumna Cecile (Ce) Funk. Bayard and Ce had two sons: Theodore (Ted; 1953–2021) and David (born 1957); they divorced in 1974. While Brattstrom was a graduate teaching assistant at UCLA, he worked at the Los Angeles County Museum (LACM) as an Assistant in Paleontology, paving the way for his graduate research projects and future collaborations. Bayard was granted honorary LACM Research Associate status in Herpetology (1961–2024) and in Vertebrate Paleontology (1962–1980). For his M.A. thesis, Bayard inventoried the fossil herpetofauna in the La Brea tar pits (Brattstrom 1952). His Ph.D. research was under the supervision of Raymond B. Cowles (1896–1975), a renowned desert ecologist and conservationist who focused on reptile thermoregulation and instilled in Bayard a lifelong passion for thermoregulation research and desert studies. Bayard’s dissertation was a seminal phylogeny of the pitvipers based on measurements of osteological characters (Brattstrom 1964), enabled by being hired as a Research Fellow in Paleoecology by the Geology Department at the California Institute of Technology. Bayard became instrumental in the field of herpetological paleontology and taxonomy; by his count over the course of his career he named at least 12 fossil snakes, turtles, lizards, and one toad. One of these, a fossil tortoise from the Miocene of California, Gopherus depressus (Brattstrom 1961) was renamed G. brattstromi in his honor by Auffenberg (1974).

Before finishing his dissertation, Bayard was hired to his first teaching position, as a lecturer in Biology at Adelphi College (now Adelphi University) in Garden City, Long Island, New York. Stories from this time in his life involve attending lectures and conducting research in the collections at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Here Bayard developed a love of teaching and embarked on some of his first wild adventures (collecting trips) with undergraduate students to pick up oversized, smelly specimens for lab study and museum collections (Brattstrom 2018a).

In 1960, Bayard became one of the first tenure-track assistant professors at the Orange County State College in Fullerton, California (now California State University, Fullerton). As inaugural faculty members at the new college, Bayard and his cohort were personally invested in developing all aspects of the university’s growth and direction. Bayard served on at least 31 Fullerton faculty and personnel committees, taught at least 20 different classes and seminars, and regularly participated in philosophical and creative salons with colleagues from many departments. One of the more improbable stories from the early 1960s involves Bayard becoming faculty advisor for the student-organized Elephant Racing Club, and then collecting and publishing the first temperature readings taken from living elephants (Brattstrom 1963). He became a full Professor of Zoology in 1966 and spent most of his academic career at Fullerton, retiring in 1994 after 34 years.

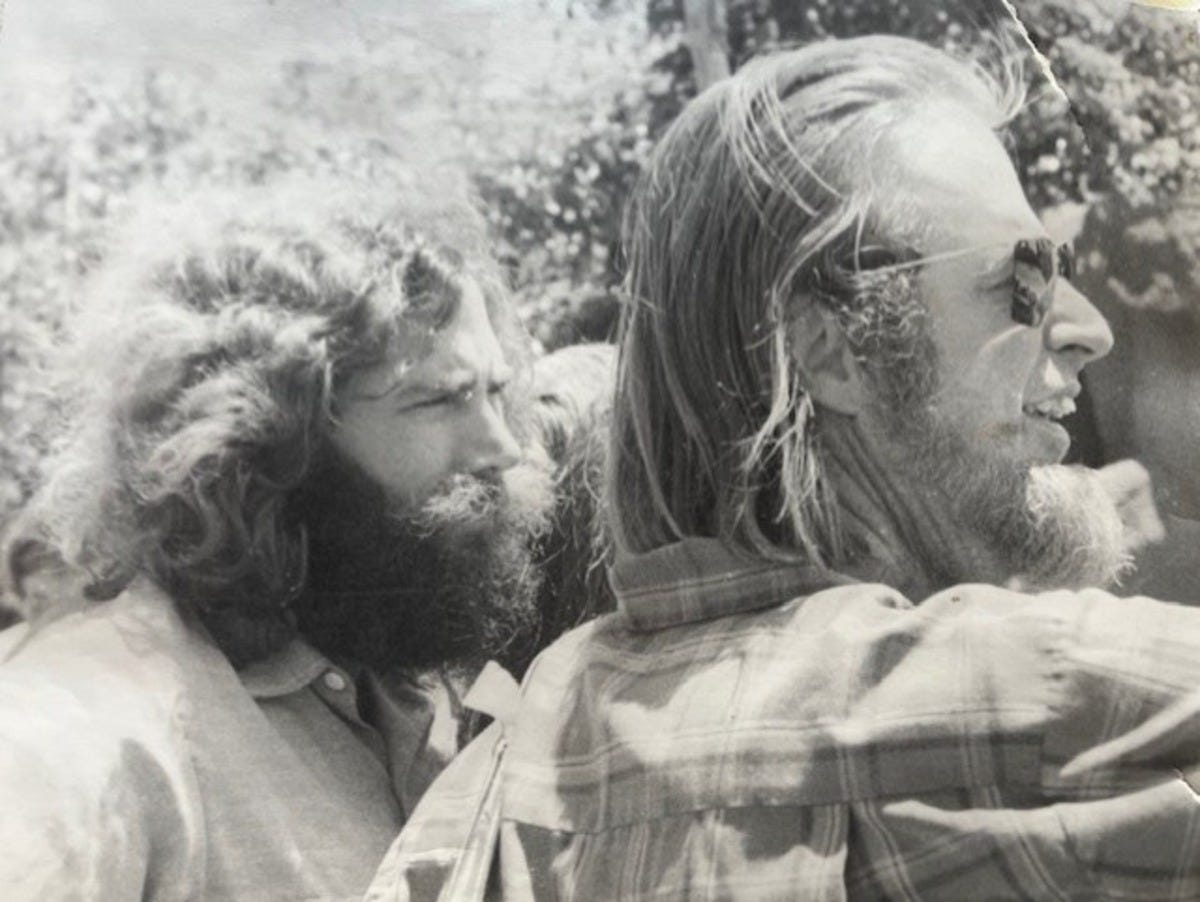

While at Fullerton, Bayard became an extraordinary mentor and teacher. He served as major advisor on the M.S. thesis and Ph.D. dissertation committees of 96 students (Figure 2) and continued mentoring graduate students until his passing.

Figure 2. Bayard Brattstrom and graduate student Hank Harlow, circa 1970s. Photographer unknown.

He was well-known for creative lectures and mentoring of non-majors in introductory biology classes, as well as immersive field biology classes teaching research skills in natural history observation and ecosystem function (e.g., Figure 3).

Figure 3. Bayard Brattstrom’s instructions to students for ecological study of creosotebush (Larrea tridentata) and other desert shrubs, from his field ecology class at California State University, Fullerton. These pages were formatted for easy inclusion into 5 ¾ X 9-inch field journal notebooks.

In the early 1970s he helped to create and teach for “The Peoples' University,” which consisted of free courses on topics requested by students. From his early teaching days into his retirement Bayard devoted much of his considerable energy to advocating for and lecturing on improvements to teaching pedagogies and grading systems. His advocacy was shared by his second wife: fellow SDSU graduate, polio survivor, and junior high school science teacher Martha Isaacs (1929-2009). They married in 1982, and co-published several books and articles, including two books on teaching and research practices (Brattstrom and Brattstrom 2008, Brattstrom et al. 2016). In 2010, the inaugural Dr. Bayard H. Brattstrom Lecture Series at Saddleback College, Mission Viejo, California was dedicated in his honor in to commemorate his influence and support of numerous students and colleagues (Figure 4); this lecture series was active until the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 4. Bayard Brattstrom with former student Tony Huntley and a fossil dolphin skull (Orange County, California) at Saddleback College, Mission Viejo, California, 2010. Image courtesy Michael Shermer.

Bayard was an exceptional field scientist, keenly interested in many different taxa, fields of study, and geographical areas. In addition to conducting research and hosting field classes at the Malheur Environmental Field Station, Burns, Oregon, and at a University of Montana Field Station (likely Flathead Lake), he traveled abroad extensively. He collected and researched herpetofauna in Mexico and in central American countries and was a visiting researcher at the Universidad de Costa Rica in 1965. Following an opportunistic volcanic eruption on the island of San Benedicto in the Pacific Ocean, he conducted field research between 1953 and at least 1981, resulting in a 60-year study of the recovery of vegetation and fauna. When this work was published (Brattstrom 2015), Bayard was awarded the Journal of Pacific Conservation Biology’s Ivor Beatty Award. After initially receiving a National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellowship in 1966 at the Department of Zoology and Comparative Physiology in Monash University, Victoria, Bayard began long-term research on Australian desert and rainforest herpetofauna. During subsequent sabbaticals and leaves of absence between 1978 and 1993, he was hosted at the University of Sydney, the University of Queensland (St. Lucia, Brisbane), and at James Cook University in 1993. Bayard was a keen observer of social behavior in humans (he trained to become a licensed marriage and family therapist) as well as in lizards and other species (e.g., Brattstrom 1974). Building on his love of the desert fauna of two continents, he and his graduate students created some of the only behavioral ethograms for North American and Australian desert lizards (e.g., Brattstrom 1971). These ethograms were developed after countless hours spent observing overcrowded lizard behaviors in laboratory terraria, in outdoor enclosures constructed in his local backyards, and sometimes in the wild.

Bayard was also a keen observer of natural history and phenology. He maintained formal field journals and informal daily field notes throughout his life, tracking the phenology of plants and animals around him. In retirement at the Horned Lizard Ranch he recorded, among other phenomena, arrival dates of resident and migratory birds and numbers of their offspring, and percent of blooming and subsequent fruiting of saguaro (Carnegiea gigantea) and Joshua trees (Yucca brevifolia). He collected local desert tortoise (now Gopherus morafkai) sightings and reported these annually to the Arizona Game and Fish Department. He also documented at least 45 individual Western Diamond-backed Rattlesnakes (Crotalus atrox) around his house through drawing their unique tail patterns (with no apparent repeat visitors). After being recognized for his lifetime contributions to desert reptile ecology during the 2019 Biology of the Pitvipers III conference in Rodeo, New Mexico, Bayard gave a memorable lecture in which he encouraged researchers to lie down in a place frequented by their animals so as to consider life from the snakes’ viewpoint. In 2021, Brattstrom received the Southwestern Association of Naturalists’ Frank Blair Eminent Naturalist Award in recognition of his life-long dedication to improving knowledge of natural history.

Bayard was a publishing machine. He authored or co-authored at least 300 scientific papers. He published 13 scientific and popular books, and contributed chapters, dichotomous keys, and/or figures for at least 19 books and conference proceedings. In addition to fossil species, he named two extant snake species (Geophis bartholomewi and Neoparea tricolor; Brattstrom and Howell 1954), and three subspecies of Sceloporus magister (S. m. tranversus, S. m. bimaculosus, and S. m. uniformis; Phelan and Brattstrom 1955). Still working on publications in the month before his passing, he submitted his last major scientific contribution. This will be a compilation of the unpublished ethogram-based master’s theses of his students entitled “Social Behavior of Southwestern Desert Lizards,” set to be published posthumously (Brattstrom 2025 in press).

In addition to academic pursuits, Bayard became a serious and well-respected consultant, delivering at least 752 consulting reports and providing expertise to zoos and over 40 private companies, state and local governments, tribal nations, and federal agencies. He conducted surveys of biological and paleontological resources and wrote environmental impact statements, focusing on desert and chaparral habitats. Herpetological focal species included Flat-tailed Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma mcallii), San Diego Horned Lizard (now known as P. blainvillii), Orange-throated Whiptail (Aspidoscelis hyperythrus), Coachella Valley Fringe-toed Lizard (Uma inornata), Western Pond Turtles (Actinemys spp.), Desert Tortoise (Gopherus spp.), and San Joaquin Valley Racer (Masticophis flagellum ruddocki, named by Brattstrom and Warren 1953). He often employed graduate students who conducted their M.S. thesis research based around the consulting jobs (e.g., Brattstrom and Bondello 1983). Some of Bayard’s favorite consulting gigs were as a herpetological expert witness during trials, for which he researched the feasibility of attempted murder by rattlesnake bite (Brattstrom 1998b) and conducted forensic herpetology with tortoise remains (in Brattstrom 2018a,b).

As a member of the “Greatest Generation,” Bayard lived a life of service outside of academic and consulting work. He was active in local and regional herpetological clubs, conservation and zoological advisory commissions, species advisory committees, and traditional civic service societies such as neighborhood associations, and the Rotary, Kiwanis, and Elks Clubs. Tellingly, in his 25-page CV (not including publications), he lists service on the Board of Governors of the Southern California Academy of Sciences, the Board of Directors of the Fullerton Youth Museum (1962–1966; President, 1962–1964), and the Board of Directors of the Orange County Zoological Society (1962–1965) under “Honors.” He promoted science outreach and education throughout his life, judging science fairs and serving on student scholarship committees while at Fullerton. In retirement he continued to be an advocate for science and education, even identifying lizards for his nurses during his last days in a Kingman, Arizona hospital.

Bayard was especially passionate about membership in professional societies, eventually becoming a member of at least 19 professional societies. Between 1962 and 1983, he served the ASIH with stints on the Board of Governors, the Gaige and Stoye Award Committees, as an editorial board member, and as Western Vice President; he was on the editorial board of the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles during 1979–1981. He was a Member of the Council for the American Association for Advancement of Science (AAAS) starting in 1965, and later represented ASIH as its voting member on the AAAS Science Council until 1990. He enjoyed organizing conferences and educational workshops in addition to presenting research, including testing the limits with unorthodox ideas, and strongly encouraged his and others’ students to attend and present at regional and national meetings. He also strongly encouraged societies to keep costs low to encourage student participation. As anyone who visited his library at the Horned Lizard Ranch or had the misfortune to be editor of a journal that moved to an online format can attest, Bayard was an avid reader and vociferous supporter of print journals. It was not pleasurable for him to read articles on a screen, and as technology became more complicated it became increasingly difficult to even access online versions.

Retirement and the Horned Lizard Ranch

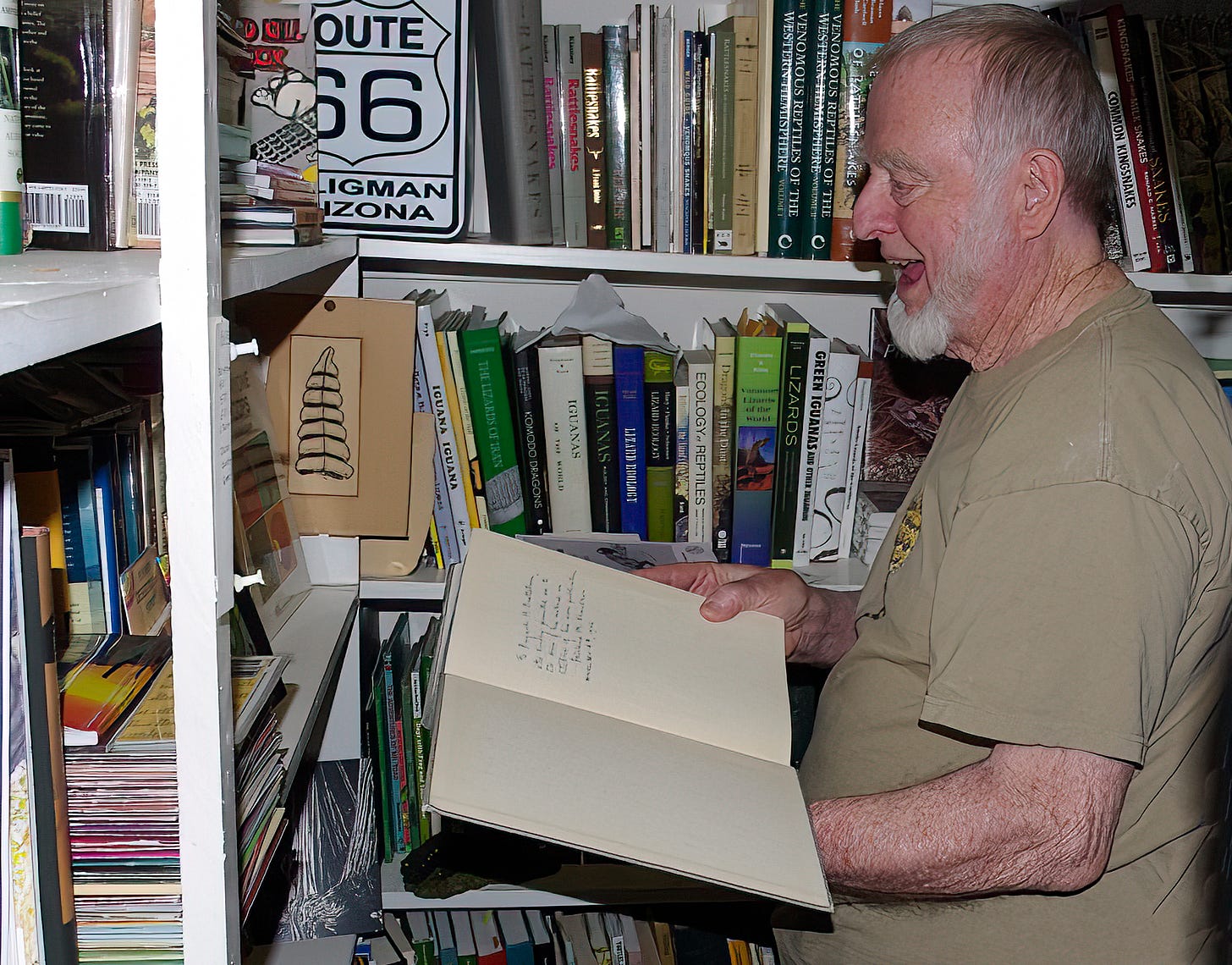

Bayard’s interests in teaching, mentoring, research, publishing continued to shine during his retirement. In the early 2000s, he and Martha purchased the property in Wikieup, Arizona that became known as the Horned Lizard Ranch (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Bayard Brattstrom outside the Horned Lizard Ranch house, November 2015. Image by Harvey Lillywhite.

They had an off-grid straw bale house built on top of a hill with beautiful 360-degree desert vistas, and Bayard became an advocate for straw bale houses and solar-based off-grid living. Not one to slow down, he kept 28 filing cabinets of research and teaching materials, data, and student papers in his office. His library contained at least 25 journal series and over 12,240 science literature, field guides, and popular books covering topics such as travel, science fiction, history, native American culture, psychology, and religion (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Bayard Brattstrom sharing his library at Horned Lizard Ranch, Wikieup, Arizona, 2014. Image by David Barker.

Bayard and Martha developed bird, mammal, and herpetofauna species checklists for the Big Sandy River area near their home (e.g., Brattstrom and Brattstrom 2007). Especially after Martha’s passing in 2009, Bayard also enjoyed visiting with former students and colleagues, neighbors, Nowak’s Herpetology classes from Northern Arizona University (Figure 7), and even strangers who’d heard about his place from neighbors, or just happened to wander by. He maintained a dizzying level of intellectual curiosity, soliciting information at conferences and through personal correspondence on theories he had, both for his own edification and for articles or books he was writing. Bayard sought out and shared information with researchers and novelists with interests in organismal, natural, and human history; paleontology; philosophy; and art.

Figure 7. Northern Arizona University Herpetology class students on a field trip to Horned Lizard Ranch, Wikieup, Arizona, 2011. Image by Erika Nowak.

Both during his academic career and in retirement, Bayard had boundless energy for working on fun and creative pursuits outside of his academic, consulting, and civic interests. He published two books of poetry, and was skilled in drawing, watercolor painting, photography (scientific and abstract), cooking, and gardening. He deeply appreciated art and collected Native American and herpetological-themed indigenous art from around the world. In his later years, he also enjoyed finding antique treasures at auctions and in thrift stores, and extensively researched the more unusual finds such as a “baby cooker” from China, designed to contain small children and keep them warm while parents were busy. As a result of his interest in art, the Horned Lizard Ranch became known for its road-side sculptures. Metal and ceramic herds of turtles, frogs, crocodylians, lizards, snakes, and African wildlife crisscrossed the road to the house, joined by nesting dinosaurs, a moose (thoughtfully preceded by a “moose crossing” sign), and a ca. 9 m long horned lizard and a bright pink and black gila monster. Bayard’s serious sense of fun and social commentary were also expressed in many roadside vignettes. The vignettes were typically made from materials found at auctions, and some told stories based on real but reimagined events. One particularly creative exhibit interpreted racial desegregation at the Augusta National Golf Club (home to the Masters Tournament) in 1990 using different colored golf clubs; another immortalized the life of Ed Ricketts, the famous marine biologist friend of John Steinbeck. Others were more ironic in tone, including a display of outsized drill bits interspersed with parts from a Model A Ford (Figure 8) and a wooden rowboat labelled “Just in Case” (Figure 9) parked uphill of the normally dry “Calli Wash” (i.e., Gerson’s Callisaurus draconoides study site).

Figure 8. “Bits and Pieces” road-side vignette at the Horned Lizard Ranch, Wikieup, Arizona, in 2020. Image by Mary Shipman.

Figure 9. “Just in Case” road-side vignette at the Horned Lizard Ranch, Wikieup, Arizona, in 2020. Image by Mary Shipman.

Bayard Holmes Brattstrom leaves behind an astounding legacy of creativity and scores of colleagues, students, and mentees who continue to be inspired by him. He is survived by his ex-wife Cecile Funk, his son David and daughter-in-law Dawne, his sisters Barbara and Susan and their families, and his assistant and dear friend Mary Shipman.

References

Auffenberg, W. 1974. Checklist of Fossil Land Tortoises (Testudinidae). Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 18:121–251.

Brattstrom, B. H. 1952. The Amphibians and Reptiles from Rancho La Brea. M.A. Thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, CA.

Brattstrom, B. H. 1961. Some new fossil tortoises from western North America with remarks on the zoogeography and paleoecology of tortoises. Journal of Paleontology 35:543–560.

Brattstrom, B. H. 1963. Body temperature of living elephants. Journal of Mammalogy 44:282.

Brattstrom, B. H. 1964. Evolution of the pit vipers. Transactions of the San Diego Society of Natural History 13:185–268.

Brattstrom, B. H. 1971. Social and thermoregulatory behavior of the bearded dragon, Amphibolurus barbatus. Copeia 3:484–497.

Brattstrom, B. H. 1974. The evolution of reptilian social behavior. American Zoologist 14: 35–49.

Brattstrom, B. H. 1998a. The circular Aesculepian temple (Tholos) at Epidauros, Greece: an early snake pit? Herpetological Review 29:79–80.

Brattstrom, B. H. 1998b. Forensic herpetology I: the rattlesnake in the mailbox attempted murder case. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 33:205–211.

Brattstrom, B. H. 2015. Bárcena Volcano, 1952: A 60-year report on the repopulation of San Benedicto Island, Mexico, with a review of the ecological impacts of disastrous effects. Pacific Conservation Biology 21:38–59.

Brattstrom, B. H. 2018a. Flying Fish, Pizza, Religion, and Sex: a Naturalist’s View of Life. Outskirts Press, Inc., Parker, CO.

Brattstrom, B. H. 2018b. Lizard Tales: People and Events in the Life of a Naturalist. Outskirts Press, Inc., Parker, CO.

Brattstrom, B. H. In press. Social Behavior of Southwestern Desert Lizards. Eco Press, Rodeo, NM.

Brattstrom, B. H., and M. C. Bondello. 1983. The effects of off-road vehicle sounds on desert vertebrates. Pp. 167–207 in R. H. Webb and H. G. Wilshire (Eds.), Environmental Impacts of Off-Road Vehicles: Impacts and Management in Arid Regions. Springer Verlag, New York, NY.

Brattstrom, B. H., and T. R. Howell. 1954. Notes on some collections of reptiles and amphibians from Nicaragua. Herpetologica 10:114–123.

Brattstrom, B. H., and J. R. Sams. 1951. The Clark Nutcracker in San Diego County, California. Condor 53:204–205.

Brattstrom, B. H., and J. W. Warren. 1953. A new subspecies of Racer, Masticophis flagellum, from the San Joaquin Valley of California. Herpetologica 9:177–179.

Brattstrom, B. H., and M. A. Brattstrom. 2007. Amphibians and reptiles of the Big Sandy River Drainage, Mohave County, Arizona (from Upper Trout Creek Junction to Alamo Lake). Sonoran Herpetologist 20:116-117.

Brattstrom, B. H., and M. A. Brattstrom. 2008. Scratch the Chalk on the Board… It Keeps the Students Awake: A Field Guide to Poor Teaching. Horned Lizard Press, Wikieup, AZ.

Brattstrom, B. H., M. A. Brattstrom, and M. E. Shipman. 2016. How to Study Rhinos. Outskirts Press, USA.

Gerson, M. M. 2022. Historical Perspectives: Bayard Holmes Brattstrom. Ichthyology & Herpetology 110:413–17.

Nowak, E. M., M. M. Gerson, and M. E. Shipman. In press. An extraordinary mentor: remembering Bayard Holmes Brattstrom (1929–2024). Herpetological Review.

Phelan, R. L., and B. H. Brattstrom. 1955. Geographic variation in Sceloporus magister. Herpetologica 11:1–14.

What an uplifting account of a life well lived. Thank you for highlighting this man and his works.

Wow, what an amazing life! I do believe he was one of those people who don’t need much sleep. He seems to have been a very busy man, and exceptionally productive.