Kyle Rittenhouse and Self-Help Justice

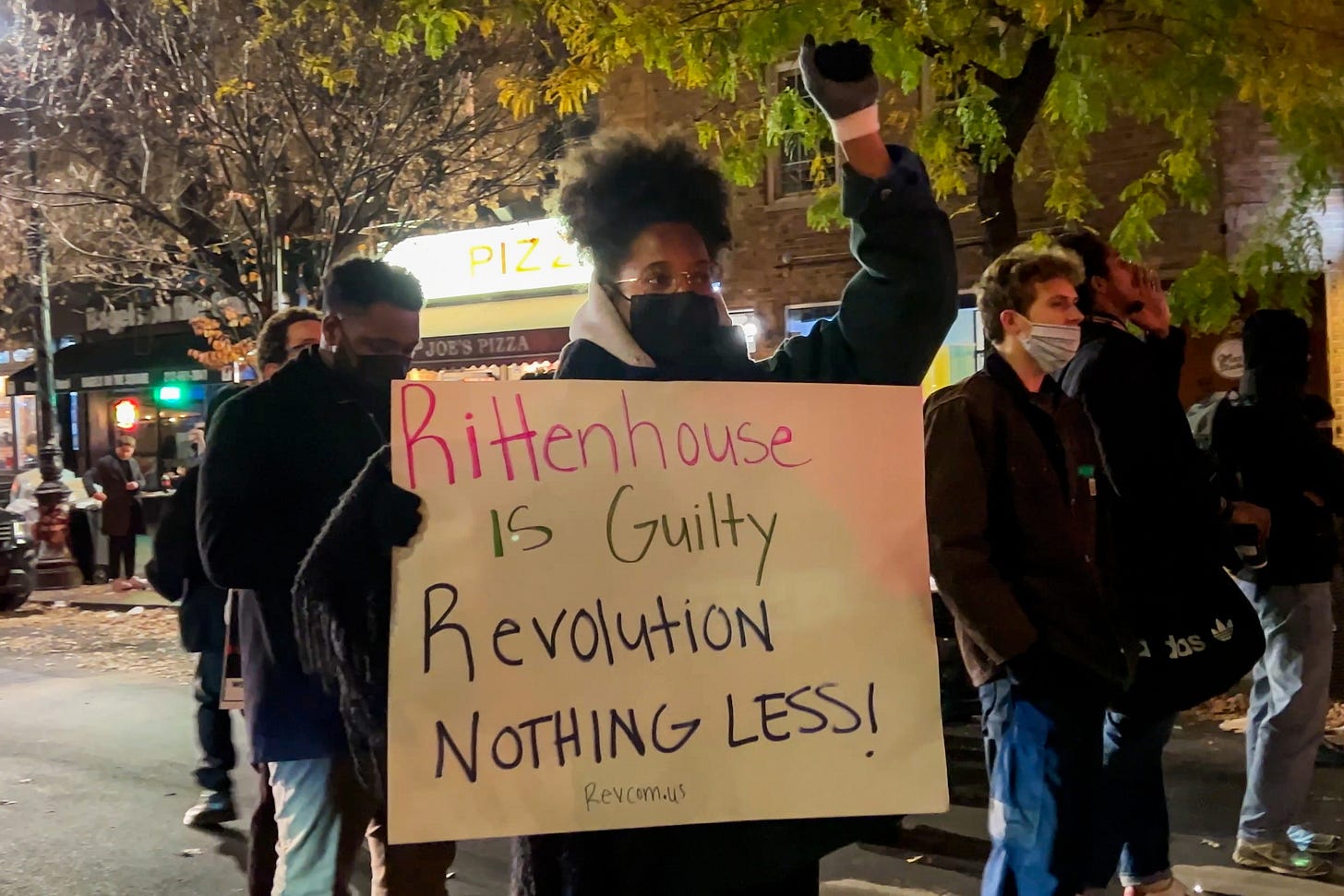

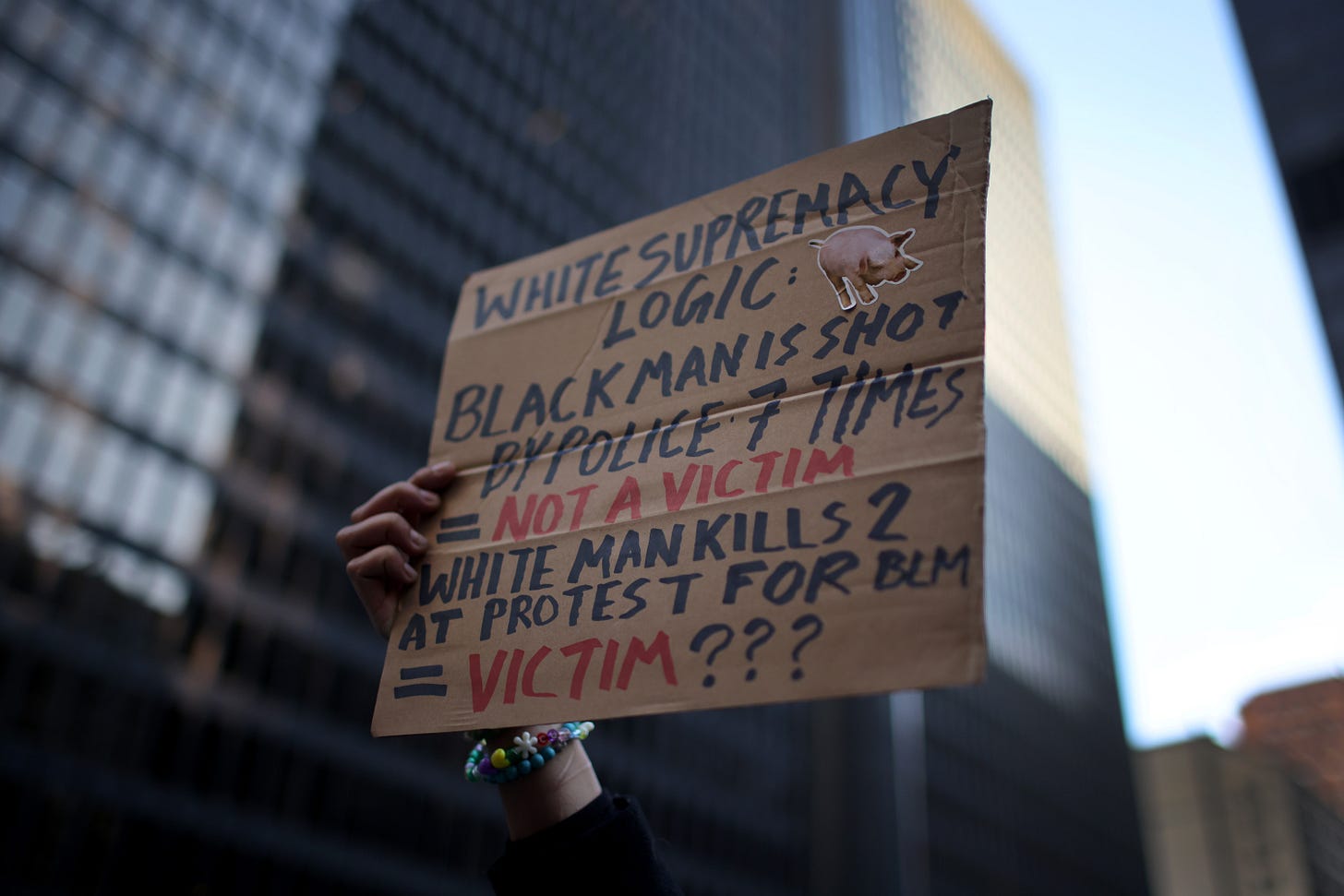

A deeper lesson on human violence and society

Like everyone else last week I was riveted by the suspense over what the verdict would be in the Kyle Rittenhouse trial. I think that the jury made the right decision to acquit Rittenhouse on all charges. The testimonies and video evidence presented in the trial shows that Rittenhouse was chased and lunged at by the first victim he fatally shot, Joseph Rosenbaum, was attacked with a skateboard by the second victim he fatally shot (Anthony Huber), and shot and wounded the third victim (Gaige Grosskreutz) who pulled out his own handgun and pointed it at Rittenhouse. Thus, it was determined, Rittenhouse acted legally under Wisconsin law to “prevent imminent death or great bodily harm to himself.”

But as I told my wife that day, if our son was 17 and announced that he was going to a protest over a highly-charged issue with racial and political overtones (in this case the police shooting of Jacob Blake), and that he was taking with him a semi-automatic AR-15 style rifle just in case things took a turn toward violence, we’d take away his gun, hide the car keys, and if necessary lock him in his room. As I tweeted that day, “Emotionally aroused testosterone-fueled males + guns = trouble.”

There are already countless commentaries on the meaning and the particulars in the Rittenhouse trial, so let me offer some reflections on what I think are some deeper lessons on human nature and society we can take from this case, starting with the concept of self-help justice. I wrote about this extensively in my book The Moral Arc, in the chapter on “Moral Justice: Retribution and Restoration,” keying off sociologist Donald Black’s explanation for why people living in civilized societies with justice systems and police forces nevertheless sometimes choose to take the law into their own hands. Black’s 1983 paper on this subject is titled “Crime as Social Control” (published in the American Sociological Review, pp. 35-45), in which he takes the well-known statistic that only around 10 percent of homicides belong in the category of predatory or instrumental violence (e.g., robbing a liquor store for cash and shooting the clerk in the process), arguing that most homicides are moralistic in nature. Most murders, says Black, are a form of capital punishment in which the murderer is the judge, jury, and executioner over a victim they perceive to have wronged them in some manner deserving of the death penalty.

Black provides examples that are as common as they are disturbing: “a young man killed his brother during a heated discussion about the latter’s sexual advances toward his younger sisters,” another man who “killed his wife after she ‘dared’ him to do so during an argument about which of several bills they should pay,” a woman who “killed her husband during a quarrel in which the man struck her daughter (his stepdaughter),” another woman who “killed her 21-year-old son because he had been ‘fooling around with homosexuals and drugs,’” and several involving disputes over automobile parking spots. Most violence, in fact, is a form of moralistic punishment, and that includes self-defense.

But what was Rittenhouse doing there in Kenosha the first place, along with all those protesters? The Constitution guarantees our right to peacefully protest, but as we’ve seen in recent years, protests often turn violent, as it did in Wisconsin. Why? The proximate explanations can be seen in the videos and imagined from the testimonies, but the ultimate explanation is because we evolved a moral sense of right and wrong, and if the state doesn’t protect our right to seek justice over those who have wronged us, we’re inclined to take the law into our own hands.

The goal of modern Western judicial systems is to prevent citizens of a nation from using force and committing violence against one another when disputes arise. Today this is conducted through two justice systems: criminal and civil. Criminal justice deals with crimes against the laws of the land that are punishable only by the state. Civil justice deals with disputes between individuals or groups, such as contract violations, property damage, or bodily injury, and the court’s say is final in determining right and wrong and appropriate damages. Criminal justice involves mostly retribution. Civil justice involves both retribution and restoration (through assessed damages). For both forms of justice, states claim a monopoly on the legitimate use of force, with the goal of deterring future crimes against citizens of the society. This is why criminal cases are labeled The State v. John Doe or The People v. Jane Roe. The state becomes the injured party. My home state of California, for example, continues to pursue charges against the film maker Roman Polanski for raping an underage girl in 1977, even though she—now a woman in her 40s—has forgiven him and has requested that the state drop the charges, and even though Polanski lives in Switzerland and has no intention of ever returning to the U.S.

This is why in areas of Western nations where citizens do not feel that the law is fair to them—as in parts of the United States where the police and courts are perceived to be racist—people often take the law into their own hands. This is why it is called “self-help justice,” or sometimes “frontier justice,” or plain old “vigilantism.” Take the case of inner city violence where crime rates are much higher than elsewhere. The primary reason for this violence is gang-related illegal drug trafficking. When a product that people want is made illegal, it does not necessarily eliminate the desire for the product; instead it shifts the economic transaction from a lawful free market to an unlawful black market—think alcohol during Prohibition, or drugs today. Because drug dealers cannot turn to the state to settle disputes with other drug dealers, self-help justice is their only option. As such, criminal gangs emerge (most famously the Mafia), which enforce a different sort of criminal justice.

Occasionally conditions arise in which ordinary citizens feel pressed to take the law into their own hands, as Bernhard Goetz did on December 22, 1984, when four young men approached him on a New York City subway in what he perceived to be in a threatening manner. At the time of this incident, New York City was in the throes of one of the biggest crime waves in American history, having seen its rate of violent crime skyrocket nearly fourfold from 325 to 1,100 per 100,000 people in only a decade. In fact, three years prior to this incident, three young men had robbed Goetz of some electronic equipment and then tossed him through a plate-glass door. One of his attackers was caught, but was charged only with criminal mischief for ripping Goetz’s jacket and released from the police station even sooner than Goetz was. The criminal went on to mug again, leaving Goetz skeptical of the criminal justice system and the police’s capacity to protect him from harm. So to protect himself, Goetz purchased a Smith and Wesson .38-caliber handgun, as was his right by the Second Amendment.

On that fateful night in 1984, the four young men boarded the subway carrying screwdrivers, intent (they later said) on knocking off video arcade machines in Manhattan. When Goetz attempted to exit the subway train, they surrounded him and demanded money. (In their trial they claimed that they had only been “panhandling” and had merely “asked” for the money instead of demanding it.) Given his prior experience, his awareness of the crime wave, and the gun in his pocket, Goetz was conditioned for confrontation. He shot the men and exited the train.

Not long afterwards, Goetz became known as the “Subway Vigilante” and was the topic of a national debate on crime and vigilantism. In response, and to show that it would not tolerate a return to the Wild West form of vigilante justice, the state criminal justice system came down hard on Goetz, charging him with four counts of attempted murder, four counts of reckless endangerment, and one count of criminal possession of a weapon. Living in what was essentially a lawless subsection of a civil society—New York City subways—Goetz reacted, in his own words, like an animal. “People are looking for a hero or they are looking for a villain. And neither is the truth. What you have here is nothing more than a vicious rat. That’s all it is. It’s not Clint Eastwood. It’s not taking the law in your own hands. You can label that. It’s not being judge, jury and executioner.”

In a civilized society, in fact, it is the state’s duty to provide judge, jury, and executioner, but the public disagreed, most siding with Goetz, and several groups established legal defense funds on his behalf. In his criminal trial he was acquitted of the attempted murder charges but served eight months for carrying a loaded but unlicensed weapon in a public place. As Goetz reflected: “What happens to me at this point is unimportant. I’m just one person. This has at least raised issues in New York. One thing I can do to show the legal system what I think of it.”

As we reflect on the Rittenhouse case, and those that came before and will surely come again, let me close with an even bigger picture of what lesson we might glean from all this. In the long history of civilization, self-help justice conducted by individuals has gradually been replaced with criminal justice conducted by the state. The former leads to higher rates of violence than the latter, due to the lack of an objective third party to oversee the process. States, for all their faults, have more checks and balances than individuals.

This is why Justitia—the Roman goddess of justice—is often depicted wearing a blindfold, symbolizing blind justice and impartiality; in her left hand she carries a scale on which to weigh the evidence, a symbol for a balanced outcome; and in her right hand she wields the double-edged sword of reason and justice, symbolizing her power to enforce the law. The system is far from perfect, but it is vastly superior to the alternative of a lawless society, or one in which citizens take the law into their own hands.

###

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University, the host of The Michael Shermer Show podcast, and the author of numerous New York Times bestselling books including: Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, Heavens on Earth, and Giving the Devil His Due. His next book is on conspiracy theories and why people believe them.

Interesting response. I'm usually accused of toeing the Republican Party line. I try not to toe any party line. I just want to know the truth, politics aside. Agreed, most of the legacy media sources mangled the story. I don't know I would go so far as to call Rittenhouse a dangerous vigilante, although the point of my essay was to note that vigilantism is the logical response to a lawless situation or one in which the vigilante doesn't feel justice is being or will be done. Rittenhouse should have never gone there with a gun, as that likely elevated the emotions and stress levels of his assailants, whom he shot. Legally, by Wisconsin law, it was self-defense, but I suspect if no one at that protest had a gun it would have just been some typical male fisticuffs with some bruised bodies and egos. When you add guns to an already volatile situation it can easily turn deadly. And, of course, I condemn the rioting and looting in Portland, Seattle, San Francisco, and other cities, such as the smash-and-grab incidents in SF recently. That's another unfortunate outcome of lawlessness. If the government signals that they will not do anything about escalating violence, as in these cities, we are going to see more and more such incidents.

Interesting analysis Gary, but the hindsight bias is blinding us on what it must have been like for Rittenhouse when he was assaulted by Rosenbaum. We can analyze the incident by milliseconds and then reason that, say, the first discharged bullet was warranted but not the rest, as if he had multiple seconds between shots while the scene was unfolding in slo-mo and could reason through each one. That's not how emotions work. The rage circuit lights up and the gun is engaged and the finger just pulls the trigger over and over. In hindsight, of course, we can break it down and see what each bullet did, but that's literally unreasonable. The ultimate preventative measure would be to not have a gun at all, or better still avoid potentially violent situations altogether. And that leads back to my main point: the police should have provided a stronger shadow of enforcement over the entire protest, including threats against property damage in the neighborhood (which is why Rittenhouse said he had gone there in the first place). A more clear-cut case of vigilantism turned murderous is that of the three white men just convicted of murder today for chasing and shooting Ahmaud Arbery as he ran through their neighborhood, with a Georgia jury rejecting a self-defense claim. I also think this was the right verdict in this case.