As a followup to my commentary on the Kyle Rittenhouse acquittal, with which I agreed, I wanted to note that I also believe that the jury made the right decision in the Ahmaud Arbery case in convicting his three assailants of murder, aggravated assault, false imprisonment, and criminal intent to commit a felony: Gregory McMichael, his son Travis McMichael, and their neighbor William "Roddie" Bryan. The case involved a now-repealed Georgia law that permitted citizen arrests, which the defendants argued gave them the right to confront the unarmed 25-year-old Arbery while he was out jogging, based on their suspicion that he was fleeing a crime. As in the Rittenhouse case, it was yet another example of vigilante self-help justice turned deadly.

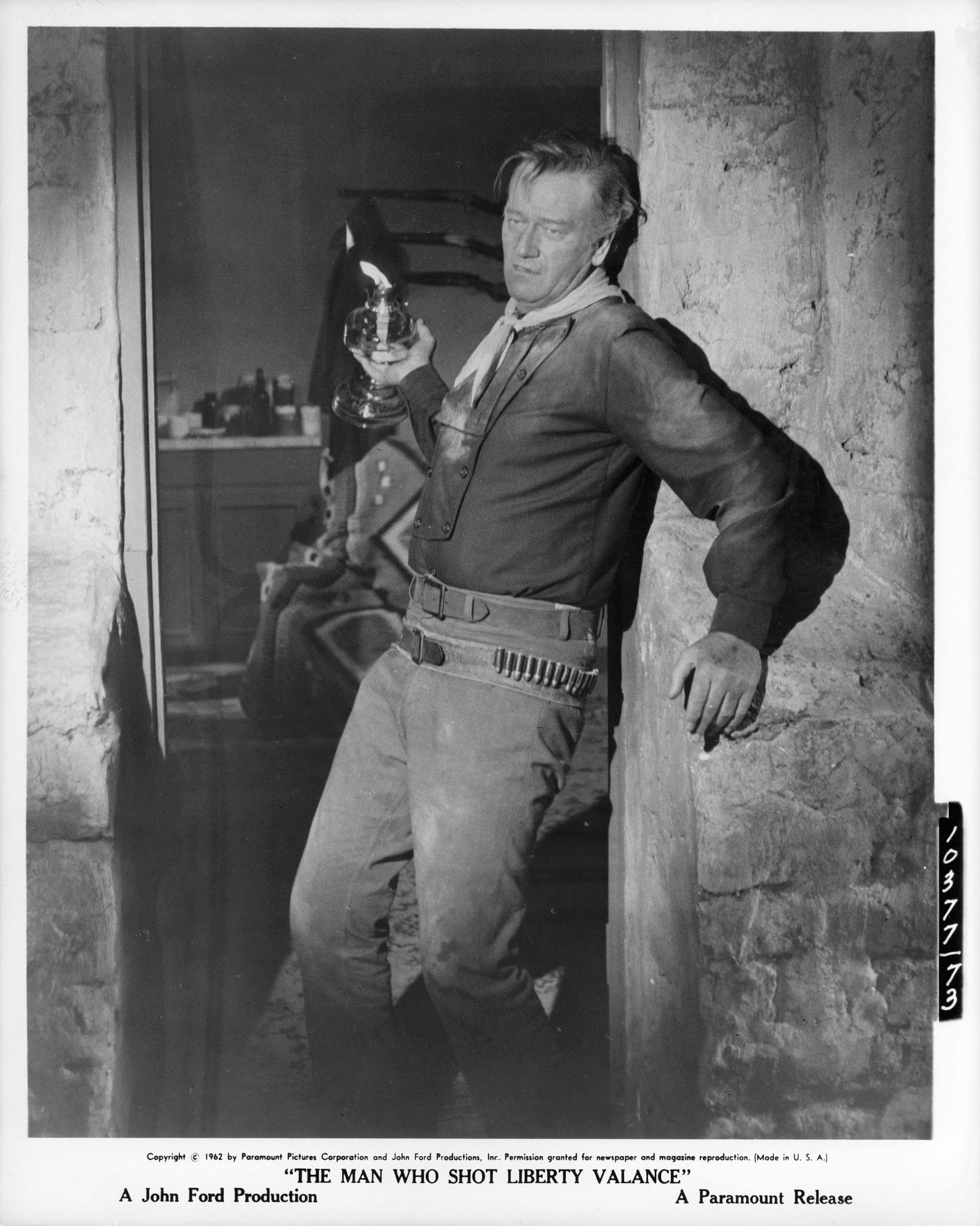

In the long history of civilization vigilantism happens when people do not believe that the criminal justice system works as it should, or where people live beyond the long arm of the law. The 4,000-year history of how this was worked out around the world may be found in the newly-published The Rule of Laws by the anthropologist of law and barrister Fernanda Pirie, with whom I just recorded a podcast episode of The Michael Shermer Show that will be released soon. It is a magisterial work that reveals in intricate detail the wide diversity of ways that people have developed to work out their differences and achieve justice. In my book The Mind of the Market I presented a fictional example of how this unfolded in the wild west of the United States, through John Ford’s classic 1962 film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, in which a clash of ethics unfolds in the frontier town of Shinbone, Arizona.

There in the dusty streets and ramshackle buildings, two self-contained and self-consistent moral codes come into conflict. One is the Cowboy Ethic, where trust is established through courage, loyalty, and personal allegiance to friends and family, and where disputes are settled and justice is served between individuals who have taken the law into their own hands. The other is the Law Ethic, where trust is established through the transparent and mutually-agreed upon rule of law, and where disputes are settled and justice is served between all members of the society who, by virtue of living there, have tacitly agreed to obey the rules. Only one of these codes can prevail.

In The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, the Cowboy Ethic is represented by two people, one good and the other evil. John Wayne’s character, Tom Doniphon, is a fiercely loyal and deeply honest gunslinger who is duty-bound to enforce justice on his own terms through the power of his presence backed by the gun on his hip. Lee Marvin’s title character, Liberty Valance, is a coarse and unkempt highwayman whose unruly behavior provokes fights with the locals, most of whom fear and loathe him. The Law Ethic is represented by Jimmy Stewart’s character Ransom Stoddard, an attorney hell bent on seeing his beloved Shinbone make the transition from cowboy justice to the rule of law. John Ford opens his film at the end of the story: the funeral of Tom Doniphon, attended by an elderly Stoddard, who is swamped by reporters inquiring why the now-distinguished U.S. Senator would bother returning to his native town to be present at the memorial services of a down-and-out gunfighter.

When they were coming of age in this territory just slightly out of reach of the law, Stoddard and Doniphon are of radically different minds about how justice should be served, each believing that the other’s strategy is either outdated (Doniphon’s gun) or naïve (Stoddard’s law). Despite this difference, or perhaps because of it, they become faithful friends, both believing that in the end, justice must prevail. When Valance arrives, it is clear that he respects only Doniphon, because they share the Cowboy Ethic that men settle their disputes honorably, between themselves. As Doniphon boasts, “Liberty Valance is the toughest man south of the Picketwire—next to me.”

But Valance’s disdain for the milksop Stoddard and his naïve notions about the effectiveness of the law knows no bounds. Entering a restaurant where Stoddard is dining, for example, Valance berates him, taunts him, and finally trips the waiter, sending Stoddard’s dinner to the floor. As Stoddard meekly tries to avoid a confrontation, Doniphon enters and stares down Valance, who snaps back, “you lookin’ for trouble, Doniphon?” In his inimitable John Wayne drawl, Doniphon responds, “You aimin’ to help me find some?” Valance caves to Doniphon’s challenge and scurries out of the restaurant. “Well now; what do you supposed caused him to leave?” Doniphon wonders rhetorically. The sardonic response from a patron in reference to the impotency of Stoddard’s philosophy reveals which ethic is still dominant: “Why it was the specter of law and order rising from the gravy and the mashed potatoes.”

Despite Valance’s relentless taunting, Stoddard holds to his belief that until Valance is caught doing something illegal, there can be no justice. When Doniphon tells Stoddard “You better start pack’n a handgun,” Stoddard rejoins, “I don’t want to kill him. I just want to put him in jail.” At long last, however, Stoddard can take the derision no more, so he decides to take Doniphon’s advice that “out here a man settles his own problems,” and turns to him for gun-fighting lessons. When Valance challenges Stoddard to a dual, the overconfident naïf accepts and a late-night showdown ensues. In a darkened street, the two men square off. Stoddard is trembling in fear while Valance mocks and scorns him, shooting first too high and then too low. When Valance takes aim to kill, Stoddard shakily draws his weapon and discharges it. Valance collapses in a heap. Having felled one of the toughest guns in the west, Stoddard becomes a local hero, building that image into political capital and working his way up from town politics to a distinguished career in the U.S. Senate. So it would appear that the Law Ethic prevailed, literally and figuratively, though the transition was resolved in the flash of a gun, moral conflict resolved.

But as the flashback continues, we learn that some time after the gunfight Stoddard discovered that he was not the fatal shooter. The man who shot Liberty Valance was Tom Doniphon. Knowing that Stoddard was no match for Valance, Doniphon lurked in the shadows, fingering a rifle, which he engaged to kill Valance at the crucially-timed moment when the two men drew their weapons. Holding to the Cowboy Ethic of loyalty and friendship, Doniphon takes the secret to his grave. When Stoddard finally reveals to a newspaper reporter the truth about who really shot Liberty Valance, the paper decides not to print the truth because, in what has become one of the most memorable lines in filmic history, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Despite this being a typical shoot-em-up western film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance contains many moral subtleties, starting with the observation that both Stoddard and Doniphon violated their principles, but they did so because this was the only means by which one moral code could displace the other. By agreeing to a duel with Valance, Stoddard adopts a form of conflict resolution that he previously deemed illegal and immoral, and after discovering the truth about who really shot Valance, he chooses to live a lie of omission and capitalizes on his unearned heroism. For his part, Doniphon violates his moral code by ambushing Valance instead of facing him man to man, and then hides the truth about what really happened, tacitly endorsing Stoddard’s faux use of the Cowboy Ethic in order to help bring about the Law Ethic to town. In fact, both men violated their own codes of morality, and with ample irony the only person who held true to his was the scurrilous Liberty Valance. But in the end, as Shinbone grew in size, the transition from one moral code to the other had to happen, and in this moral homily it was friendship and loyalty that facilitated the change.

The fictional Shinbone embodies any small community in transition from an informal moral system to a formal legal code and system of justice. As long as population numbers are low and everyone in a community is either related to one another or knows one another through regular interactions, the code of the cowboy can work relatively well to keep the peace and ensure trust and social stability. But when communities expand and population numbers increase, the opportunities for unchecked violations of such informal codes expand exponentially, requiring the creation of such social technologies as codes, courts, and constitutions.

This is why the breakdown of law-and-order such as we’ve seen in cities like Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco resulting in widespread rioting, looting, and most recently smash-and-grab raids on retail stores, witnesses Liberty Valance wannabes who lack even a cowboy ethic or a culture of honor. These are honorless thugs who should be brought to justice…legally.

###

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University, the host of The Michael Shermer Show podcast, and the author of numerous New York Times bestselling books including: Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, Heavens on Earth, and Giving the Devil His Due. His next book is on conspiracy theories and why people believe them.

Dr. Shermer, thank you for this article. I remember seeing this enjoying the moral play (and the play between Wayne, Stewart and scary Lee Marvin). 40+ years on, I'd say that the moral story is more subtle, both in the movie and in reality. The establishment and maintenance of law and order is dependent on lawful society having the ability and right to exercise force to that purpose.

There can be, and could not be in the movie, any hope of establishing and sticking to a "rule of law" morality without the ability to prevent Valance clones from exercising their penchant for getting their way, or just having fun, through use or threat of violence.

More broadly, and perhaps sadly, moral codes only have power over those who subscribe to them. They do not exist as a transcendental force for good; they need the actions of determined humans to make them a livable reality. Turning the other cheek is an excellent principle for spiritual growth. It is of only limited worth to those protecting their children.

Dr. Shermer,

Regarding the recent lawless group criminal activity, my gut tells me that many readers and the "man on the street" can appreciate an enlightened after-the-fact analysis such as your article. But we want more. I'm sure I'm not alone when I state that most law-abiding citizens would like to know what causes/allows this type of "smash & grab" behavior, as well as looting, destructive rioting, etc., and what can be done to prevent or mitigate this lawlessness. I have some ideas, but they don't mean much coming from me and without solid research behind them. Nevertheless, some thoughts I'd propose are: 1) Single-parent broken families with no strong authority figures around for many years. 2) Defund the police movements. 3) Normalization of this behavior from SJ groups & activists, glamorization of these memes in certain music & pop culture idioms; 4) A general tendency for criminal justice systems to be too lenient on these types of crimes & guilty perpetrators; and a general tendency in our society nationwide to be out-of-balance with regard to social pressures exerted on people to be law-abiding citizens. I'm specifically thinking of the tilt toward too much emphasis on what I'd term feminine forces versus a lack of a proper balance of masculine forces. This can be thought of as Yin/Yang, or simply nurture/compassion/empathy/freedom vs control/order/accountability/responsibility. Too much of the masculine leads to a police state and fascism. But too much femininity leads to what we're seeing too much of these days. The big question is: how do we go about steering the culture back to a balance of the two before things descend into a state of chaos, violence and anarchy that we may not be able to get out of without a civil war. Thanks for your time. Quest R.