Losing My Religion

From Elder in the Jehovah’s Witnesses religion to proponent of scientific naturalism, by Michael Bigelow

In several of my books I have recounted my own journey from born-again Christian to religious skeptic, in the context of understanding how beliefs are formed and change (in The Believing Brain), how religious and faith-based beliefs differ (or at least should differ) from scientific and empirical beliefs (in Why Darwin Matters), and the relationship of science and religion: same-worlds model, separate-worlds model, conflicting-worlds model (in Why People Believe Weird Things). As a result, over the years I have received a considerable amount of correspondence from Christians who want to convince me to come back to the faith, along with one-time believers who recount their own pathway to non-belief. At my urging after emails revealing autobiographical fragments of his own loss of faith, in this edition of Skeptic guest contributor Michael Bigelow narrates his sojourn from Elder in the Jehovah’s Witnesses religion to proponent of scientific naturalism. As he recalls in this revealing passage from the essay below:

A literal interpretation of the Bible proved incorrect. Humans were not created in 4026 BC, nor was the earth engulfed by a flood 4,400 years ago. I was wrong. My personal discovery categorically rendered the Bible’s account of natural history as false. This revelation cast doubt on the entirety of the Bible.

—Michael Shermer

Losing My Religion

In 2008, I faced one of the most uncomfortable moments of my life. For Jehovah’s Witnesses, the memorial of Jesus' death is the most significant event of the year. It is a solemn occasion in which a respected Elder addresses a packed Kingdom Hall, filled with believers and visitors. That year, I delivered the talk and managed the ritual passing of the wine and unleavened bread. Many attendees praised me afterward, claiming it was clear that God’s spirit was upon me. However, for nearly four years before that evening, I had ceased praying and believing and was deeply troubled by the hypocrisy of teaching things I could no longer accept as true.

An even more distressing day occurred in 2012 when I publicly renounced my ties with Jehovah’s Witnesses. A former friend described my departure as a “nuclear blast” that devastated the three congregations I had once served. My decision to leave based on conscience resulted in immediate and complete shunning by all my former friends, my family, and even my two adult sons.

Turning Points

I was born into a large extended family of Jehovah’s Witnesses in 1961 in San Diego, California. Our family of eight led a life typical for Witness households: we didn’t celebrate holidays, birthdays, or participate in patriotic events and after-school activities. My entire social circle was within the religious community, and our Saturdays were dedicated to door-to-door preaching. This lifestyle felt completely normal to me as a child.

During the 1960s, Jehovah’s Witnesses were taught that Armageddon was imminent and strongly suggested this would occur in 1975. We believed that on this day, God would destroy all who were not part of our faith, creating a deep sense of urgency to save not just ourselves but others. Driven by this belief, my father moved our family from the comfort of Southern California to frugal living in Northern New England, aiming to reach an underserved community with our teachings.

In New Hampshire, at our new Kingdom Hall, I met a young lady who would become my wife. At just twelve years old, we were both deeply committed to our faith, known among Jehovah’s Witnesses as "The Truth," and we knew we would eventually wed. Despite our parents' efforts to keep us apart, it seemed inevitable that we would be together. After graduating high school, we married young, securing minimum wage jobs and making ends meet with second-hand furniture and tight budgets.

I progressed through various positions of responsibility, both in our congregation and at the manufacturing company where I worked. Together, we raised and homeschooled our two sons, continually striving to live up to the commitments of our dedication to God.

In 1991, I was appointed as an Elder in our local congregation, a role laden with significant responsibilities. My duties included teaching at congregation meetings, providing guidance to those struggling, leading preaching efforts, and speaking at large conventions. Following in my father’s footsteps, I established a reputation as a dedicated minister. Despite my commitment, I harbored private doubts. Natural disasters and biblical accounts like the Noachian flood, which seemed improbable, troubled me. I was also disturbed by the notion of God allowing Satan to corrupt His perfect creation. We were taught to manage such doubts through prayer and meditation, a strategy that sufficed until innovations like Google Earth introduced new perspectives that challenged my views further.

Deconversions

Accounts of shunning, deconversion, and abandoning supernatural beliefs are increasingly common today. While my story isn't unique in its occurrence, it is distinct in its unfolding. Many are leaving Jehovah's Witnesses due to the organization's strict control, unfulfilled prophecies, evolving doctrines, prohibition of blood transfusions, biased translations of the Bible, and mishandling of child sexual abuse cases.

These are valid reasons to leave, but my departure was driven by something else. When I realized the biblical narrative of natural history couldn't possibly be true, my entire belief system collapsed. Yet, I continued to serve as a teacher, shepherd, and public figure in the organization for five more years, knowing I was an atheist. This period was a personal torment for which I still feel remorse. Looking back, I can't see how I could have chosen differently. Here is how it all unfolded.

I have always had a profound love for the outdoors, and spending time in the mountains has been a significant part of my life. In the late 1960s, my grandparents took my brothers and me on a road trip from San Diego to the Sierra Nevada mountains in Central California. The majestic, snow-capped and rugged terrain captivated my imagination. This experience left a lasting impression, and by the mid 1980s I began organizing annual backpacking and climbing trips to the Sierras. Each spring, I would meticulously plan these trips from New Hampshire, pouring over maps, guidebooks, and equipment lists.

By the early-1990s, the Palisade range of the Sierra had become my personal sanctuary, notable for the ranges’ largest active glacier. The first time I observed the glacier from an elevated viewpoint, I noticed it was shrinking. At the glacier's base lay a horseshoe-shaped moraine nearly a hundred feet high. Below the moraine's rim, a glacial pond of milky, silty water formed, scattered with broken granite and ice. This observation troubled me; something significant was amiss, yet it remained just beyond my understanding.

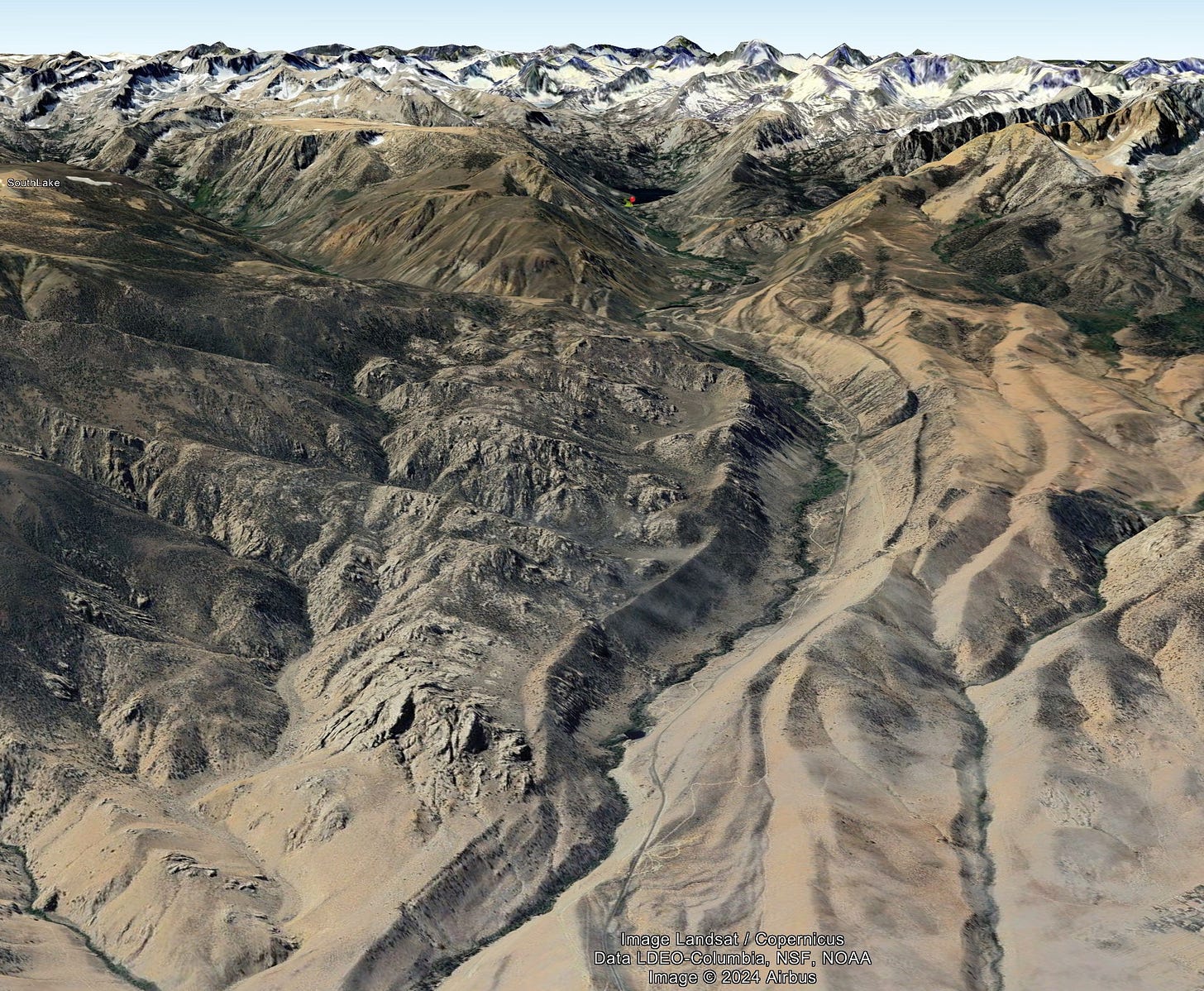

Palisade Glacier. Photo by the author.

From the perspective of day-age, fundamentalist Christians, it is believed that the entire planet was submerged underwater 4,400 years ago during Noah's flood. Thus, every existing landform—whether a canyon, glacier, desert, cavern, or mountain—either existed under water at that time or formed naturally afterward. I didn't contemplate these ideas when I first saw that glacier or when I climbed the 14,000-foot mountains surrounding it. Yet, a seed of new doubt was planted.

By the late 1990s, I had a new tool for planning my trips to the Sierra: Google Earth. This technology allowed me to view satellite imagery of the entire mountain range. I could meticulously plan climbing routes, select camping spots, and observe glaciers—not only those that were still active but, more intriguingly, those that had vanished. The disappearance of glaciers suggested ice ages, a concept that I was not ready to accept as it contradicts Jehovah’s Witnesses' teachings, which deny such geological periods.

Business Interlude and Deep Questioning of the Faith

In 1999, the company I had been with since my teenage years offered me a job in Asia. At that time, I was managing two of their operations in New England. They had recently acquired a company in Taiwan and wanted me to oversee their manufacturing in China. My wife and I deliberated over this opportunity, with our primary concern being the ability to maintain our spiritual commitments and contribute to a local congregation in Taiwan. After reaching out to the headquarters of our religious organization, we learned there was an English-speaking group in the city we would be moving to, and they welcomed our participation. Encouraged by this, we decided to relocate.

Upon moving to Taiwan, I soon realized the necessity of learning Mandarin Chinese to succeed in my role. Motivated by this challenge, I dedicated myself to studying with an intensity I had never shown before. In high school, my focus had been on my future wife rather than academics, making me a lackluster student. However, in Taiwan, I quickly learned Mandarin and developed effective study habits that significantly changed my life's direction. This deep dive into the language not only helped in my immediate job but also enabled me and my business partners to eventually acquire the Asian company, securing our financial future. Additionally, working in locations away from my family provided me with the private space and time to deeply research and reflect on significant topics, further enriching my understanding and perspectives.

In the early 2000s, while living in Asia, I continued planning trips to the Sierra Nevada. By then, Google Earth's satellite imagery had greatly improved, allowing me to see individual boulders and trees. This tool became indispensable for both planning excursions and simply enjoying the landscapes from afar. Around 2003, a particular land feature near Bishop, California, caught my attention and profoundly shifted my perspective. There, a small river emerges from the high country and runs through a wide, empty glacial moraine into the arid Owens Valley (see Google Earth image below). The moraine, a pristine trench once filled by a glacier, is starkly visible, stretching nearly to the desert floor. This observation challenged my previous beliefs: it seemed highly unlikely that this landform was ever submerged underwater or formed shortly after a flood. As I reviewed images from all the earth’s great mountain ranges, I found similar features. This realization opened a floodgate of curiosity and skepticism about the traditional narratives I had accepted.

Religious Dogma vs. Carbon Dating

The first research book I purchased was Glaciers of California: Modern Glaciers, Ice Age Glaciers, the Origin of Yosemite Valley, and a Glacier Tour in the Sierra Nevada by Bill Guyton. This book ignited a thirst for knowledge that grew exponentially. Studying glaciers led me to explore broader geology, which in turn introduced me to plate tectonics and scientific dating methods. These concepts opened the door to pre-history and the works of scholars like Jared Diamond, Steven Mithen, and many others. As I delved deeper, consuming books, downloading scientific papers, and visiting field sites, I was desperately seeking any evidence to affirm the Bible's accounts of natural history. Internally, I struggled with my faith-based commitment that "I can't be wrong," but the mounting evidence made me fear that I was losing the argument against established scientific consensus.

As I delved into pre-history, I frequently encountered carbon dating—a method I had been taught to distrust. From the 1960s until the early 1990s, Jehovah's Witnesses employed pseudo-scientific arguments to discredit the reliability of carbon dating. Reflecting on these apologetics with a better understanding of logical fallacies and flawed reasoning, I now recognize those arguments as circular, appealing to authority, and rooted in motivated reasoning. Despite my resistance, the evidence supporting carbon dating seemed overwhelming. In my quest to align my beliefs with factual accuracy, I had to personally validate carbon dating's efficacy. I came across a statement from Carl Sagan, who said, "When you make the finding yourself—even if you're the last person on Earth to see the light—you'll never forget it." This sentiment resonated with me deeply; I had to experience this realization firsthand. Sagan was right—I will never forget the moment I accepted the truth of carbon dating.

During the early 2000s, part of my research turned to the peopling of the Americas, a captivating area of paleontology that held particular significance for me at the time. According to 17th-century biblical chronologist James Ussher, humans were created from dirt in 4004 BC, specifically on October 22. Jehovah’s Witnesses adopt a similar timeline, placing human creation at 4026 BC. Arriving at Ussher's date involves recording and counting forward or backward from known events based on the ages of biblical kings and patriarchs. This chronology is accepted as accurate by many biblical literalists. However, if evidence showed that the Americas were populated thousands of years before these dates, it would profoundly challenge this timeline and compel me to reconsider my beliefs further.

As I delved into the peopling of the Americas, I discovered that the ash and pumice layer from the eruption of Mt. Mazama (now Crater Lake) serves as a precise stratigraphic marker. At Paisly Cave and Fort Rock Cave, archaeologists found human artifacts both within and beneath the Mt. Mazama volcanic tephra layer. These artifacts included campfire remains, hand-woven sagebrush sandals, grinding stones, projectile points, basketry, cordage, human hair, and the butchered remains of now-extinct animals, such as camelids and equids. Many of these artifacts were carbon dated, with results ranging from 9,100 to 14,280 years before present (BP). Therein lies a hurdle—those pesky carbon dating references. I struggled to reconcile these dates with my previous beliefs, as they suggested human presence in the Americas long before the biblical timeline of human creation.

The abundant artifacts found within and beneath the debris from Mt. Mazama prompted researchers to pinpoint the eruption's date more accurately. In 1983, Charles Bacon estimated the eruption occurred around 6,845 years +/-50 (BP) using the beta counting method of carbon dating on burned wood samples found in Mazama's lava flows. A more refined date was published in 1996 by D.J. Hallet, who dated the eruption to approximately 6,730 BP, with a margin of error of +/- 40 years. This estimate utilized the more advanced Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) carbon dating technique on burned leaves and twigs mixed with Mazama tephra in nearby lakebed sediments. Despite the improved methodology, my skepticism persisted because it still relied on carbon dating, a technique I was still reluctant to trust fully.

The quest for a more accurate date of the Mt. Mazama eruption led to significant advancements in 1999 when C.M. Zdanowicz and his team published a paper with a revised eruption date. They leveraged the precise nature of annual layers in Greenland Ice Cores, hypothesizing that they could pinpoint a near absolute year for the eruption by identifying Mazama's volcanic signatures within the ice. Starting with calibrated carbon dates from previous research as a baseline, they sampled layers above and below the target area, searching for traces of Mazama.

The team found volcanic glass and other chemical markers consistent with those found near the eruption site. Zdanowicz published a date range of 7,545 to 7,711 years before present, aligning closely with previous carbon dating results. This discovery was a profound moment of humility and awakening for me; the precision of carbon dating not only pinpointed the location of Mazama tephra in the Greenland ice core but also demonstrated the reliability of this dating method. It confirmed what many scientists had long understood: carbon dating is a powerful tool for establishing historical timelines, and these were in direct conflict with my religious beliefs.

The End of the End

A literal interpretation of the Bible proved incorrect. Humans were not created in 4026 BC, nor was the earth engulfed by a flood 4,400 years ago. I was wrong. My personal discovery categorically rendered the Bible’s account of natural history as false. This revelation cast doubt on the entirety of the Bible. When biblical authors wrote of a literal flood and Adam and Eve as the first humans, they were unaware of their inaccuracies. This prompted me to investigate the origins of the Old Testament. I concluded that this collection of books was crafted to forge a grand narrative, one that provided the people of Israel with a national identity and a distinguished status before God as His chosen people, dating back to the creation of the first humans.

If there was a definitive End of Faith date for me, it would be December 26, 2004. Witnessing the catastrophic effects of the Sumatra earthquake and tsunamis, and having experienced another earlier and massive earthquake in Taiwan firsthand, I was deeply shaken. During a period when I was already grappling with new and challenging information, I saw our volatile planet claim hundreds of thousands of lives. This led me to a stark realization: "This is God’s planet. Either He caused this, or He allowed it to happen." Just days after the disaster, I considered a third, more profound possibility: God does not exist. He didn't cause the disaster nor did He allow it; He simply isn't there. With this realization, my constant wondering, doubting, and blaming ceased. The peace I found in accepting this personal truth is indescribable.

Despite realizing that truth, fear of the unknown future and the potential devastation to my loved ones and their trust in me as a teacher and shepherd kept me living a lie. For many more years, I endured the heavy burden of this deceit, which led to terrifying, public panic attacks, some of which occurred before large audiences. This period was marked by intense internal conflict as I struggled to reconcile my public persona with my private understanding. Although it took years, I eventually had to leave the religion.

The Aftermath

Rejecting the Bible, which had been the cornerstone of my faith, propelled me toward scientific skepticism. Like many before me, I was drawn to the writings of Michael Shermer and works featured in Skeptic magazine. My departure from biblical teachings spurred me to explore questions about belief, the brain, and supernatural claims. The insights of thinkers like Carl Sagan, Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett, Bertrand Russell, Guy P. Harrison, Robert Green Ingersoll, and Thomas Paine solidified my embrace of scientific naturalism. Their eloquent articulations reinforced and expanded upon the truths I had come to recognize on my own.

But what of my life now? What about my former hope of living forever on a paradisiacal earth? What of my loved ones and my marriage? I have witnessed many who have left their faith struggle to cope with the reality that this life is all there is. Our purpose is what we decide to make it. No one has, or likely ever will, live forever. The concept of a religious afterlife is a comforting illusion, a fortified barrier constructed to shield us from the fear of death.

I've discovered that I've become a better person as a non-believer than I ever was as a believer. There's a kind of grotesque self-assuredness that comes from believing you have the only true answers to the universe's most important questions. Such certainty naturally breeds a tendency toward dogmatism in all aspects of life. Regrettably, some of this dogmatic attitude lingered even after I abandoned my faith. Initially, I felt compelled to make my immediate family—especially my wife—understand what I had learned. This approach was unwise and unkind. I have since moved past that phase. My wife and sons are aware of my beliefs and my rejection of what I consider falsehoods. I desire their happiness within their faith as Jehovah's Witnesses, striving to be the best people they can be. This is particularly important for my wife, who deeply needs and cherishes her beliefs. I know of no other couple who have managed to survive and thrive under similar circumstances, and I am committed to not letting go of that.

Since renouncing my supernatural beliefs, I've grown more tolerant of others' faiths, though I still cannot condone the terrible acts or political agendas that sometimes arise from religious doctrines. However, I remain acutely aware that many people on this "pale blue dot" rely deeply on the hope and peace their faith provides. As long as these beliefs do not result in harm, I see them as fundamentally benign. This perspective allows for a respectful coexistence in our diverse world.

As for what the future holds, I cannot say. If someone had described my current life to me 25 years ago, I would have been incredulous. Yet here I am, leading a life full of wonder and satisfaction. I intend to make the most of each day until the very end—when the sun goes dark on my last day, so will I.

Thank you, both Michaels, for presenting this captivating story. Another wonderful transformation. I want to comment on one quote from MB:

"However, I remain acutely aware that many people on this "pale blue dot" rely deeply on the hope and peace their faith provides. As long as these beliefs do not result in harm, I see them as fundamentally benign."

At base this seems to be almost tautological and unhelpful, i.e. "As long as the beliefs are not bad, they are good." Might the beliefs be neutral? But more importantly, perhaps the beliefs are intrinsically bad or inevitably lead to bad behaviors. Maybe Christopher Hitchens was right when he asserted that religion poisons everything.

If a person lives their life based on fundamental falsehoods about reality, the cosmos, and life, how can this not lead to maladaptive behavior and increased probability of harm to self and to others?

I am just not persuaded by Michael Bigelow's complacency or optimism about religious beliefs.

The argument I have with the author is only his alluding to religious faith as fundamentally benign. Not so, as the headlines prove everyday. The amount of suffering, suppression, torture and death in religious contexts is no less than what we have observed among communists, dictators and authoritarians. Or more actually if you include head count. More people suffering under misguided religious beliefs today than ever lived on earth previously...