One Day with a Great Teacher

A half century ago I walked into a college classroom...and never looked back. Some reflections on the value of education

"Better than a thousand days of diligent study is one day with a great teacher."

—Japanese Proverb

Fifty years ago—the Fall of 1972—I matriculated at Glendale Community College. It was not just that I wanted to get my General Education courses out of the way for free (although that was a solid post-hoc rationalization), but that upon graduating high school I had no idea what I wanted to study, much less what the process of higher education was even all about. Preparation for taking the SAT consisted of my Crescenta Valley High counselor telling me the test was the upcoming Saturday, after which I returned to the batting cage. I do not recall my exact score beyond being somewhere in the mediocre middle of the “bell curve,” whatever that was. Community colleges are for people like me, and Glendale College fulfilled its preparatory mission.

Glendale College from around the time the author attended. Author’s collection.

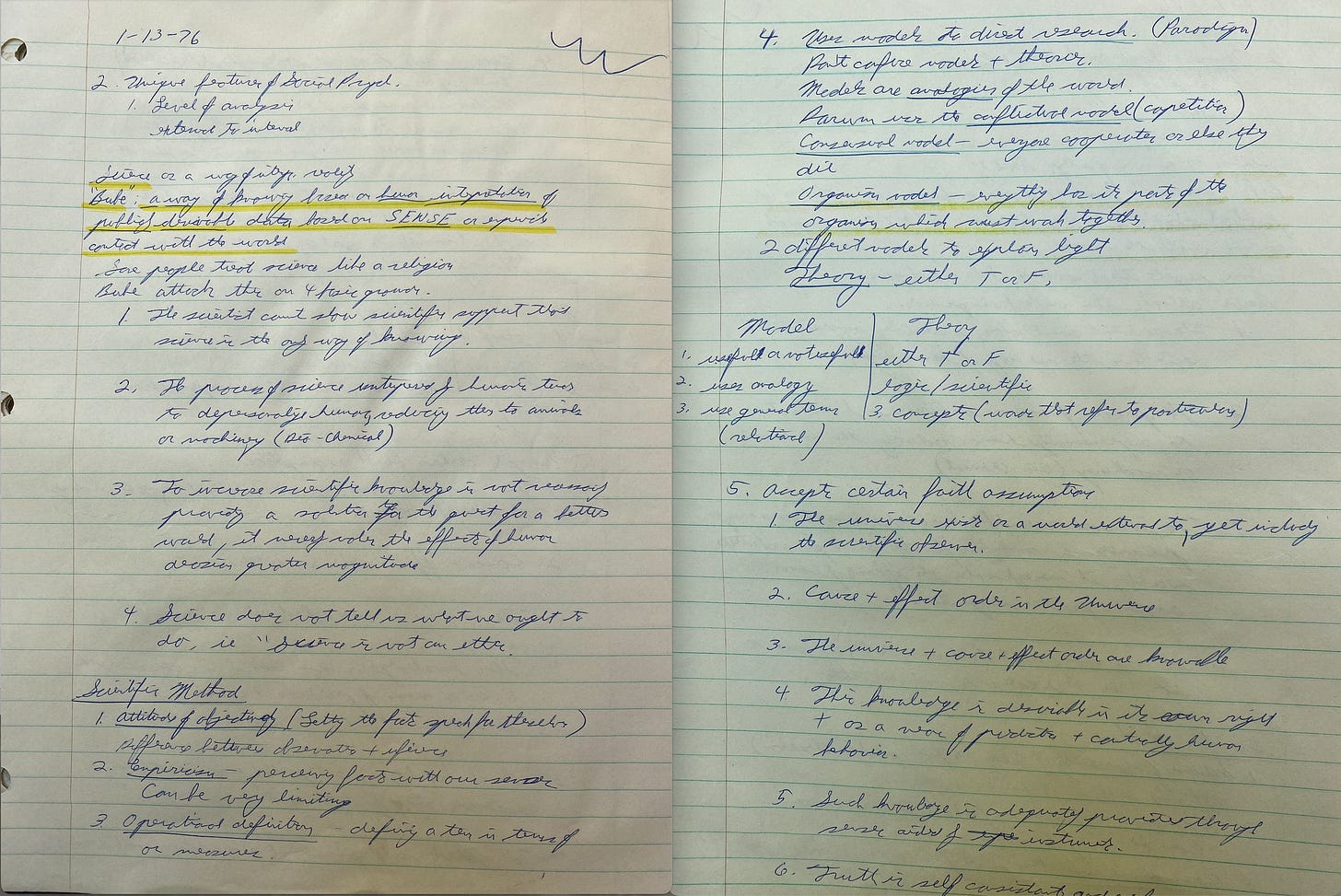

The first class I enrolled in was Astronomy 101, taught by Dr. Richard Hardison, who in fulfilling the Japanese proverb that serves as the epigraph for this essay, was worth a thousand days of diligent study. As I was clueless what classes to take, this selection was made because I was a devoted Trekkie before there even was such an appellation (the series began on my birthday six years prior, September 8, 1966), and since Star Trek had something to do with astronomy that was close enough to tick the course box on enrollment day. Here are the first two pages from my course notebook (remember those?) from day one (I will transcribe some passages from my notes below as I am told my handwriting is nearly illegible). Note the top left reference to Erich Von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods (the book that put ancient aliens on the cultural map) along with Dr. Hardison’s opinion of it—”Bad News!”

Professor Hardison was not only an energetic (almost frenetic) lecturer, he made each class session feel like it was going to be the most important subject anyone could ever study! The speed of light…inconceivable! Kepler’s Laws of planetary motion…extraordinary! Looking out into space is looking back in time…bewildering! Dr. Hardison also employed clever pedagogical techniques, for example, positioning himself in different parts of the room for otherwise boring rote memorization tasks, such as learning the constellations, as scribbled down here (with a current vague sense of where he was standing for each page).

Richard Hardison was not only my first college professor, he also saved me from the mediocrity of aimless wandering and ignited a fire to devote my life to learning and teaching. He became a lifelong friend. One memory, among many, was that Dick began to sign his missives with his last name, Hardison, which he then shortened to H, which he then spelled out as Atich, which he subsequently abbreviated as A. Egghead humor. Here from a photo collage at his memorial service is how I remember him around the time he was my teacher:

Aitch was such a polymath that he also taught Philosophy 101 (remember, this was a community college where über specialization was not mandated), so naturally I took that course, along with his Psych 101 course. I even audited his special honors course for his best students, which I had to plead to join since I wasn’t even remotely one of them. Here are a couple of pages from that 1973 philosophy course, with notes on “rules for practical conversation,” which would come in handy in my career. These include: picking the right person and occasion for a conversation, recognizing bias and fallacies such as emotive words, ad hominem, hasty generalizations, redundancy, and special experience. Then there was what is now called steel-manning—“to understand the other viewpoint restate it in your own words,” and “never disagree with the person unless you can explain why you think so (why he’s wrong).” Finally, Dr. Hardison reflected that “there’s no end to a great conversation,” and that was certainly the case with him, and it has been that way with most of the conversations I’ve had throughout my life.

As all college students know, word of mouth is the best way to find out who the best professors are at a college or university (is it Rate My Professor today?), and the word in the corridors of Glendale College was that this descriptor best fit history professor Earl Livingood. I took one course—archaeology—and was hooked. His History of Western Civilization trilogy (Ancient, Medieval, and Modern) was followed by U.S. History, the notebook and opening page from which reveals much about how history was taught in that era:

This is a representative slice of academia before the postmodern turn in the 1980s away from the Western focus on the past. Note especially the starred date of 1789 as the year when U.S. history really began—when the Constitution took effect and united the otherwise disparate independent colonies. Technically that’s correct, although the 1619 Project reminds us that there was a lot of history pre-1789, not all of it especially morally uplifting (although it goes too far in the other direction in its emphasis on slavery as the core feature of the new republic). Professor Livingood was such an engaging storyteller that dusty historical figures would come alive in his classroom, and I dedicated my book Denying History, in part, to Earl (who later became a close friend and thus the familiarity).

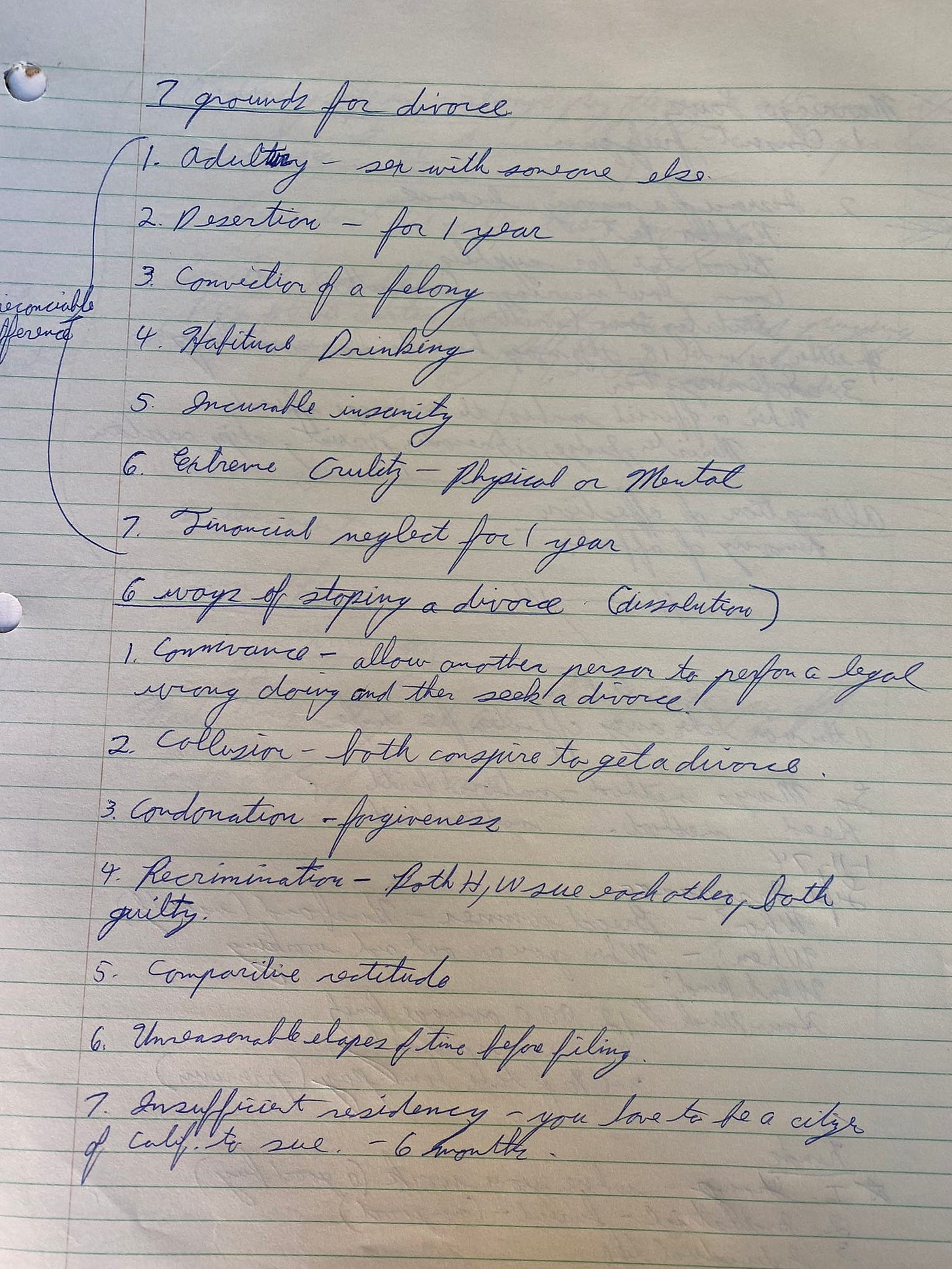

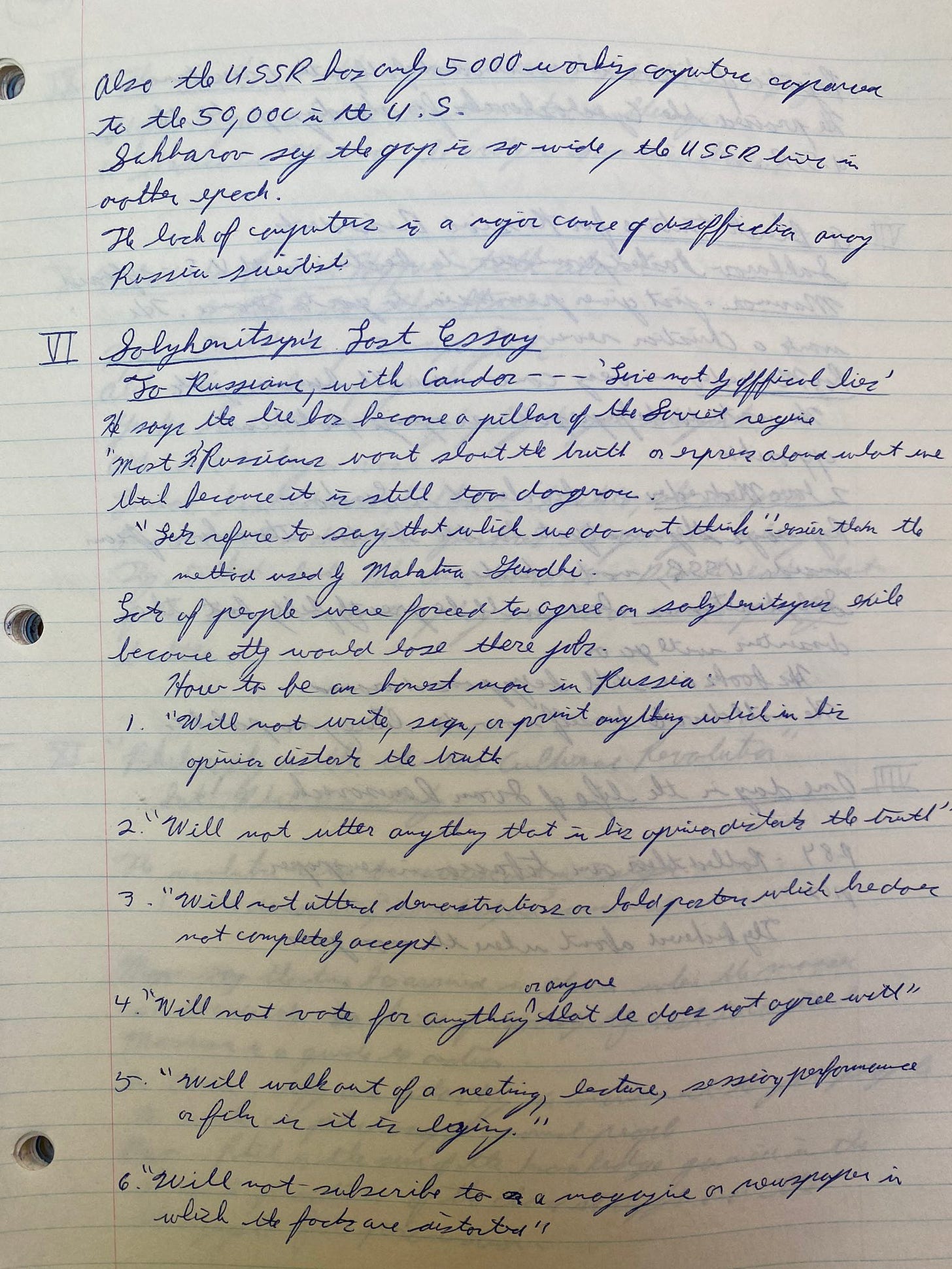

On the lighter side of my higher education at Glendale, there was the psychology course whose title escapes memory but what was, in essence, “sex and marriage,” although it included, as in my notes below, seven grounds for divorce, including adultery (for which I can’t believe I had to scribble down a definition), “desertion for 1 year” (no more, no less), “conviction of a felony” (any of them?), and “incurable insanity” (that’ll do it every time).

The notes for sexual abnormalities is especially telling, since in 1973 homosexuality (#9) was still in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) as a psychiatric disorder (expunged later that year). I’m not sure what my “T.V.” annotation means under frigidity, other than your partner would prefer the small screen to you?

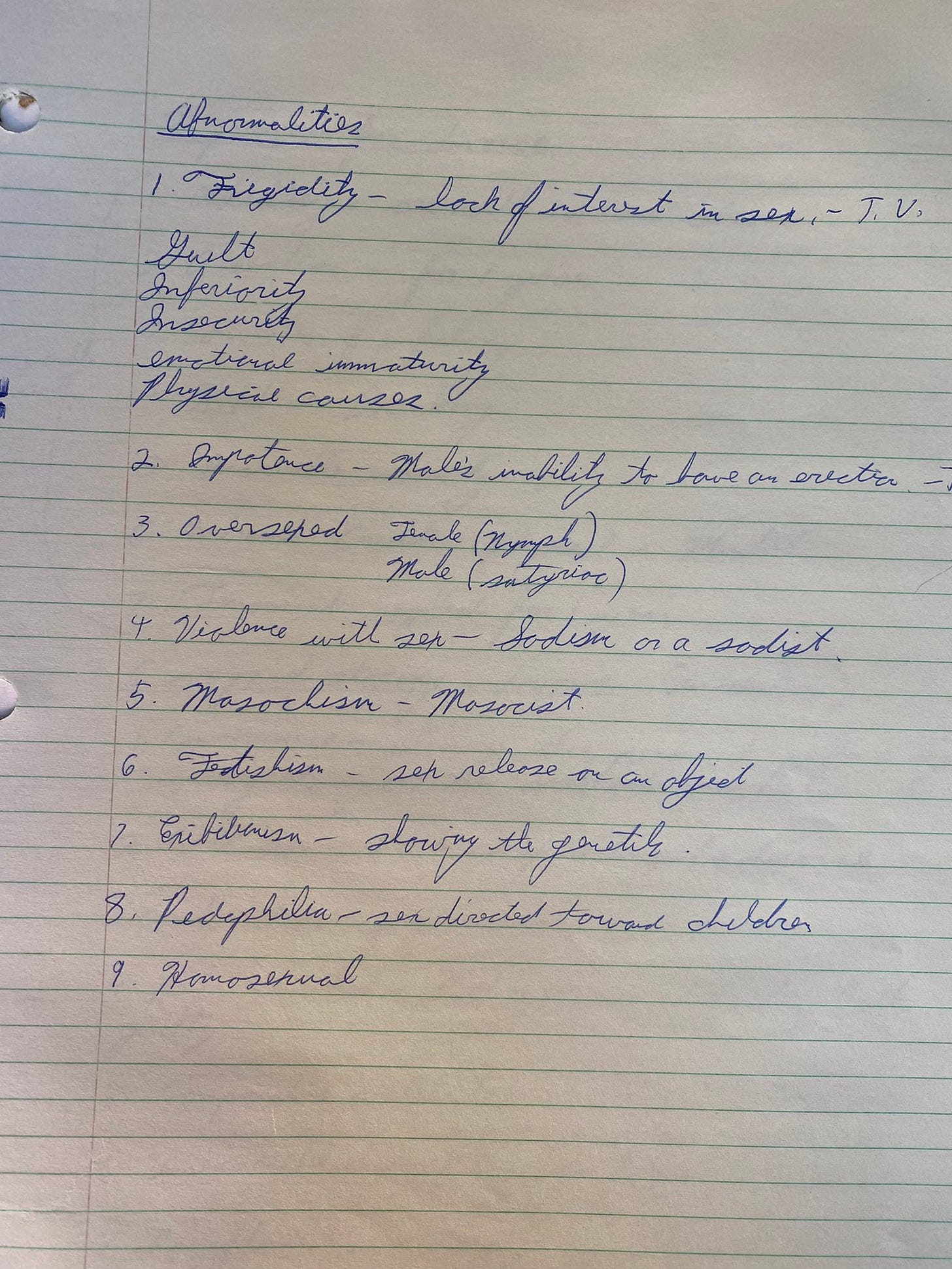

Another page of notes with missing enumerated instructions about sex (what did I miss?!), informs students in the early 1970s that “men are often ready for orgasm sooner than women” (you don’t say), that men and women enjoy sexual stimulation and need orgasms equally (however long it takes), that “size of clitoris makes no difference in desire” (see, size doesn’t matter!), that one should limit playing with the clitoris too much as it “turns her off” (citation needed), and that the breasts, vagina, and inner labia “enlarge during sex.” At this time in my life, however, it would have been challenging for me to even locate some of these anatomical features, much less follow such specific directions. Let’s just say there’s no substitute for hands on instruction with verbal and nonverbal guidance from one’s partner.

Perhaps I should have been more attentive to whomever it was who annotated my notes on September 17, 1973, for Philosophy 116: Ethics, in the upper right corner:

(Note as well the reference to Mortimer Adler and the Great Books, a set of which I still have in my library.)

Another philosophy course introduced me to Immanuel Kant, the quintessential moral absolutist:

Here are some moral absolutist commandments: “You should act in such a way that your actions would become a universal law,” “only do what everyone else would safely do,” “act in a way that regards people as ends in themselves” and, thus, “the individual needs to obey the law.”

That sounds straightforward enough, but anyone who made it to the next set of lectures knows the exceptions: Nazis come to your door and demand to know if you’re hiding Jews in your home, and you are. Do you tell the truth because you would never want to universalize lying? Of course not! Why? Because the consequences of telling the truth means the murder of innocent people. Ergo, lying is acceptable if the consequences are dire. Enter consequentialism as an ethical principle.

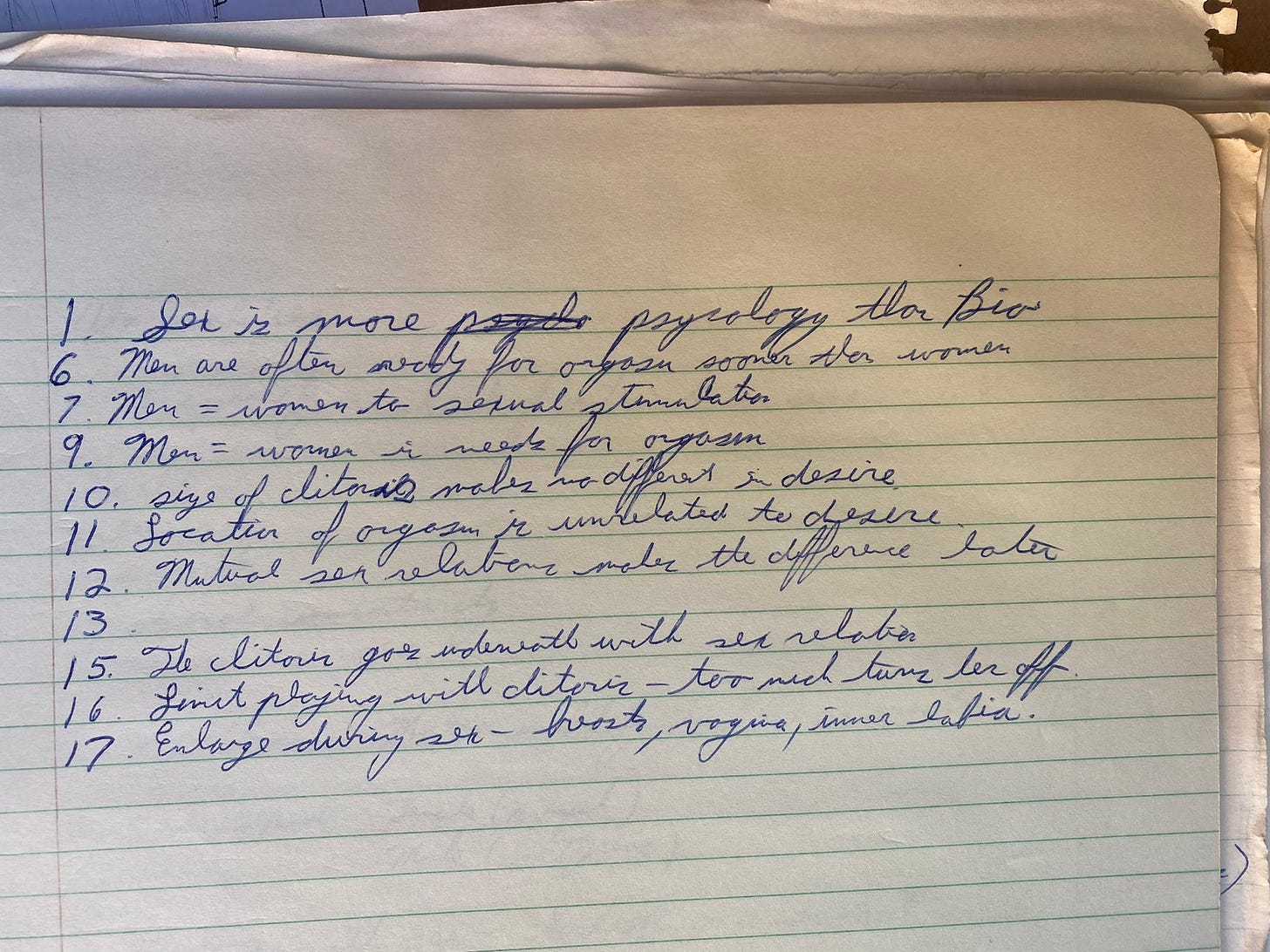

Interestingly, pages later I came across my notes on Solzhenitsyn’s Lost essay “Live Not By Lies,” in which the great Russian dissident instructs his readers on how to be an honest person in Russia, including:

1. “Will not write, sign, or print anything which in his opinion distorts the truth.”

2. “Will not utter anything that in his opinion distorts the truth.”

3. “Will not attend demonstrations or hold posters which he does not completely accept.”

4. “Will not vote for anything or anyone that he does not agree with.”

5. “Will walk out of a meeting, lecture, session, performance or film if it is lying.”

6. “Will not subscribe to a magazine or newspaper in which the facts are distorted.”

Fortunately this is no longer a problem in Russia…

From Glendale College I transferred to Pepperdine University, a Church of Christ institution that had just migrated its campus to the spectacular mountains overlooking the Pacific Ocean in Malibu. I went there, in part, because I was a Born-Again Evangelical Christian, so in addition to attending chapel twice a week (required), I took courses in the Old and New Testaments, the life of Jesus, and the writings of C. S. Lewis. Although all this theological training would come in handy years later in my public debates on God, religion, and science from a skeptical perspective, at the time I studied it because I believed it, and I believed it because I unquestioningly accepted God’s existence as real, along with the resurrection of Jesus, and all the other tenets of the faith as Capital T Truths.

My years at Pepperdine—living in Malibu, sharing a dorm room with a professional tennis player from New Zealand named Chris Gunning (Paul Newman called once to arrange lessons, causing my mother to nearly faint when I told her that I actually spoke to one of her minor deities), playing ping pong and monopoly with a bunch of jocks in Dorm 10 (women were not allowed in the men’s dorms, and vice versa), hearing speeches by President Gerald Ford and H-Bomb father Edward Teller, and studying religion and psychology under exceptional professors—are among the most memorable of my life. Here are some of my notes from the course on Jesus, and those on the writings of C.S. Lewis (Screwtape Letters my fave), both taught by the incomparable Tony Ash:

I soon discovered, however, that in order to earn a Ph.D. in theology one had to master four languages—Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and Aramaic—and since I found even Spanish to be taxing, this career choice was problematic. When my advisors also warned me about the questionable university job market for theologians, and my parents began to wonder aloud what I was planning to do for a living, I switched to psychology, where I discovered the language of science, in which I flourished. Theology is based on logical inquiry, philosophical disputation, and literary deconstruction. Science is founded on empirical data, statistical analysis, and theory building. For my style of thinking the latter was a better fit, and to this end Professor Ola Barnett was my thousand-day mentor who guided me with discipline and affection into a professional career in the social sciences. (She also once told me that I was far too serious and that I needed to develop a sense of humor, advice I took to heart, however feebly I may have implemented it.) Here are some of my notes from a statistics course I took on the Analysis of Variance, a core tool in social science to tease out the relative influence of several possible causal variables.

Although the math is mostly lost on me now, the answer to question 3 on the right page is especially poignant for the current replication crisis on why it is necessary to choose specific comparisons before running the experiment. My answer (employing the old student trick of repeating the question to stretch out the answer): “You must choose specific comparisons before the experiment because if you don’t, you will be post-hoc in your thinking thereby wishing the greatest success for your results, thereby choosing the 2 means with the greatest difference between them, thus increasing the possibility of a type I error.” Yup, that’s still a problem in the social sciences.

As for the following pages, I haven’t any idea what I was on about here and they might as well have been printed in Hebrew, Greek, Latin, or Aramaic.

In my notes for Social Psychology I found this lecture on the scientific method to be especially noteworthy inasmuch as, in point 5, I would not today consider these tenets of science to be “faith assumptions”, namely:

1. The universe exists as a world external to, yet including the scientific observer.

2. Cause and effect order in the universe.

3. The universe of cause and effect order are knowable.

4. This knowledge is desirable in its own right and as a means of prediction and controlling human behavior.

5. Such knowledge is adequately provided through senses aided by instruments.

6. Truth is self-consistent.

We do not assume these things to be true based on faith; they’re grounded in experience of how the world (and our mind) works.

I graduated from Pepperdine University in the Spring of 1976, here with my mother in attendance, both of us in the requisite 1970’s bellbottom pants (arguably the worst fashion decade in the history of the world):

After Pepperdine I was accepted into a graduate program at California State University, Fullerton in Experimental Psychology, as evidenced here (with one of the ubiquitous experimental subjects of the day)…

…which involved running experiments with rats and pigeons in Skinner Boxes under the guidance of Professor Douglas Navarick in his lab, herewith my lab mate John Chelson (with the other common organismal participants in psych labs)…

…again, in the full That ‘70s Show look…

In addition to the rockin’ cool IBM Selectric II Typewriter with correctable ribbon (in the black cover above) on which I typed my Master’s thesis, Navarick’s lab also featured (below) the newfangled Hewlett-Packard programmable calculator and accompanying scientific instruments that were known back then as pencils and paper…

…along with this massive computer that ran the Skinner Box experiments, still there in the lab when I visited Doug in 2014, still operating, and still programmable with this tray of wires:

My thesis, “Choice in Rats as a Function of Reinforcer Intensity and Quality,” was not exactly a page-turner, but testing the Matching Law—that organisms would match their behaviors (pressing levers in a Skinner Box) to the reinforcer intensity (sucrose) and quality (sucrose and salt)—consistently showed that they don’t. Under-matching was the finding, which apparently my faculty committee found important enough (or at least not completely unimportant) to award me a Master of Arts in Psychology (thank you Douglas Navarick, Margaret White, and Michael Scavio).

Before I took Margaret White’s course in ethology—the study of animal behavior from an evolutionary perspective that, among other eye-opening exercises, found me at the San Diego Zoo staring down a silver-back gorilla for a day—I took an undergraduate course in evolutionary biology taught by an irrepressible professor named Bayard Brattstrom, a herpetologist (the study of reptiles) and showman extraordinaire. The class met on Tuesday nights from 7:00 to 10:00 pm, during which I discovered that the evidence for evolution is rich and undeniable, and the arguments for creationism that I had read during my years as an Evangelical empty and duplicitous. After Bayard exhausted himself with a three-hour display of erudition and entertainment, the class adjourned to the 301 Club in downtown Fullerton, a nightclub where students hung out to discuss The Big Questions, aided by adult beverages. Here is the inimitable Bayard Brattstrom:

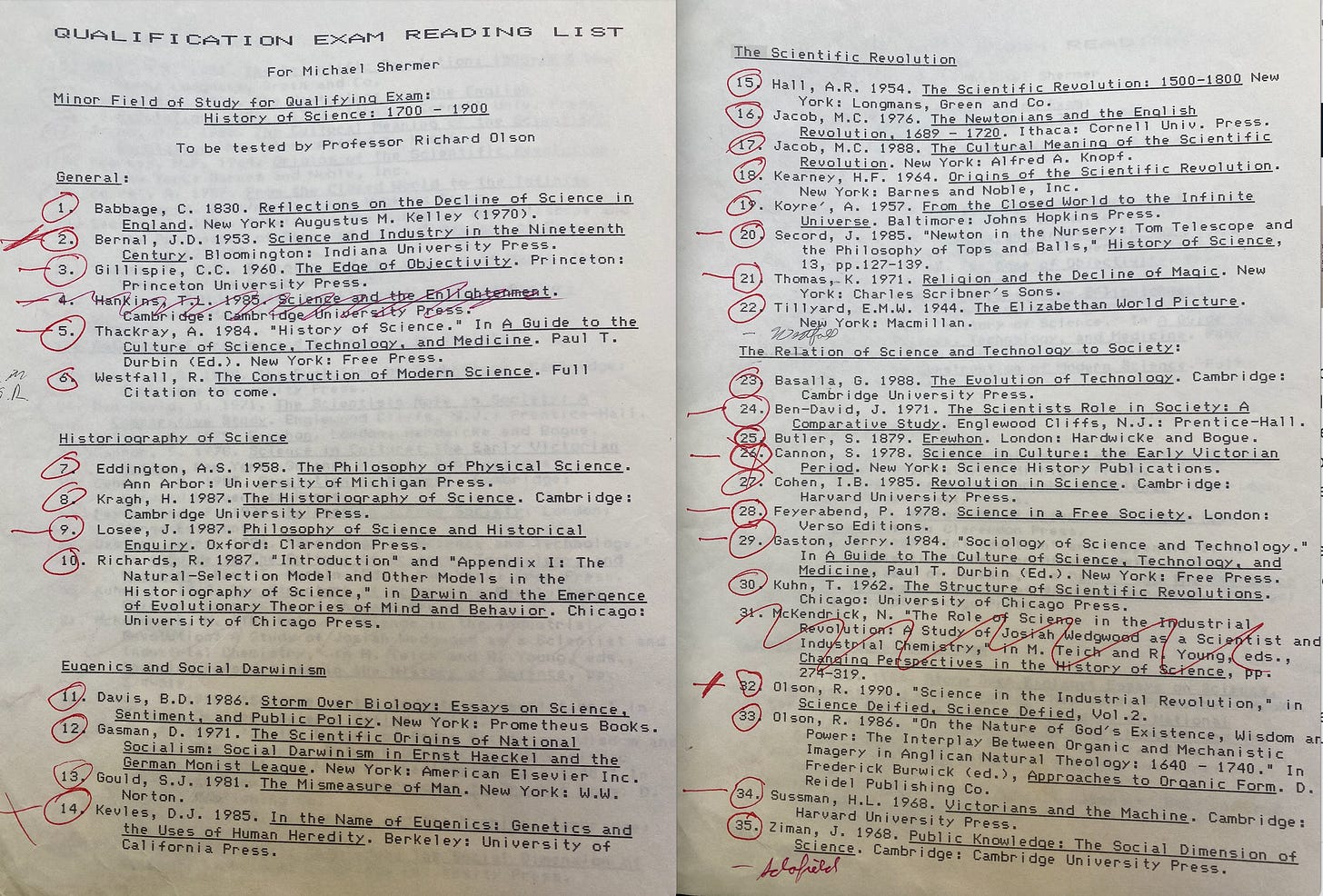

What an M.A. in Experimental Psychology didn’t get me was into a Ph.D. program or a full-time faculty position at a community college, so I wandered over to the CSU Fullerton placement office to find a job, which was as an editor at a cycling magazine (the only bankable skill I had was writing), and that contingent connection led me to spend the 1980s racing bicycles and teaching Intro Psych at Glendale College (it helps to know people). After a decade of bike racing I returned to graduate school in a Ph.D. program in the History of Science at Claremont Graduate University where I had another Great Teacher named Richard Olson, who nurtured me not only into the world of academia, but into the public arena of scientific debate. One of Professor Olson’s lasting influences among many came when I was preparing for my oral exams, based on this reading list:

They could ask me anything from any or all of these sources, so I prepared condensed notes for each, hoping I could have that crutch in front of me as I faced the tribunal. Nope. Richard told me that in the real world of scientific debate and disputation—particularly live events at conferences or in the media—notes have to be in one’s head as there’s no time to fumble through crumpled pages. I have been so preparing for real-world oral exams ever since.

The other attribute of Dr. Olson that led me to his door in search of a new mentor was that he was the scientific consultant on James Burkes’ documentary series The Day the Universe Changed. It’s a good metaphor for what a Great Teacher can do—change your universe. So now, as I enter the classroom again after I first took a chair in Astronomy 101 that long gone half century ago, I nurture the hope that maybe—just maybe—someone sitting out there will be inspired to learn and grow and share that knowledge and love of wisdom with others, for that is the true value of education.

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the host of The Michael Shermer Show, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University. He is the author of numerous bestselling books, including Why People Believe Weird Things, The Believing Brain, and The Moral Arc. His next book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believes the Irrational, which you can pre-order here.

Beautiful personal recollection of your academic history, Michael. Thank you for sharing it...

As a teacher - I really enjoyed reading this and what a wonderful closing paragraph! It captures the essence of the profession. Your students are so lucky to have you as their professor!