Protopian Progress

A review of Iwan Rhys Morus's How the Victorians Took Us to the Moon: The Story of the 19th-Century Innovators Who Forged Our Future. Pegasus Books. 2022.

Note: a shorter version of this review essay was published in the Wall Street Journal on December 8, 2022, available here.

In intellectual histories and popular commentaries on science and technology there is a tension between a retroactive vision of a golden-age past that assuages our dismay over present troubles (WMDs, climate change), and a millenarian-like idea of progress that sees our times as the culmination of an inevitable march of progress from primitive dystopia to techno-utopia (Internet, smart phones). In practice, science and technology are protopian in nature—incremental progress in small steps toward improvement, not perfection. As the futurist Kevin Kelly describes his neologism: “Protopia is a state that is better today than yesterday, although it might be only a little better. Because a protopia contains as many new problems as new benefits, this complex interaction of working and broken is very hard to predict.”

Iwan Rhys Morus’s rich but judicious narrative of How the Victorians Took Us to the Moon perfectly presents a protopian history of how nearly all of the scientific and technological advances we think of as emerging ex nihilo in the late 20th century in fact had their origin in the 19th century, “a place that was both an extension of the present and wholly different from it,” Mr. Morus notes. “The Victorian future was built around progress. Their world was not static any longer; their universe was in a constant state of evolution, and just as nature evolved, Victorians thought that society should evolve as well.”

The discovery of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, for example, demonstrated that without an outside source of energy (like the sun) entropy increases, energy dissipates, systems run down, warm things turn cold, metal rusts, wood rots, weeds overwhelm gardens, and societies fall apart, so progress requires human intervention to carve out niches of order. These Victorian “transformationists” also turned to Darwin’s theory of evolution to argue, in Morus’s description, that “it was not just planets that had emerged from cosmic dust, but life as well, slowly working its way up the ladder of complexity towards humankind. Radical social thinkers clung to ideas like these as evidence that change needed to happen in society too—that progress was part of the proper order of things.”

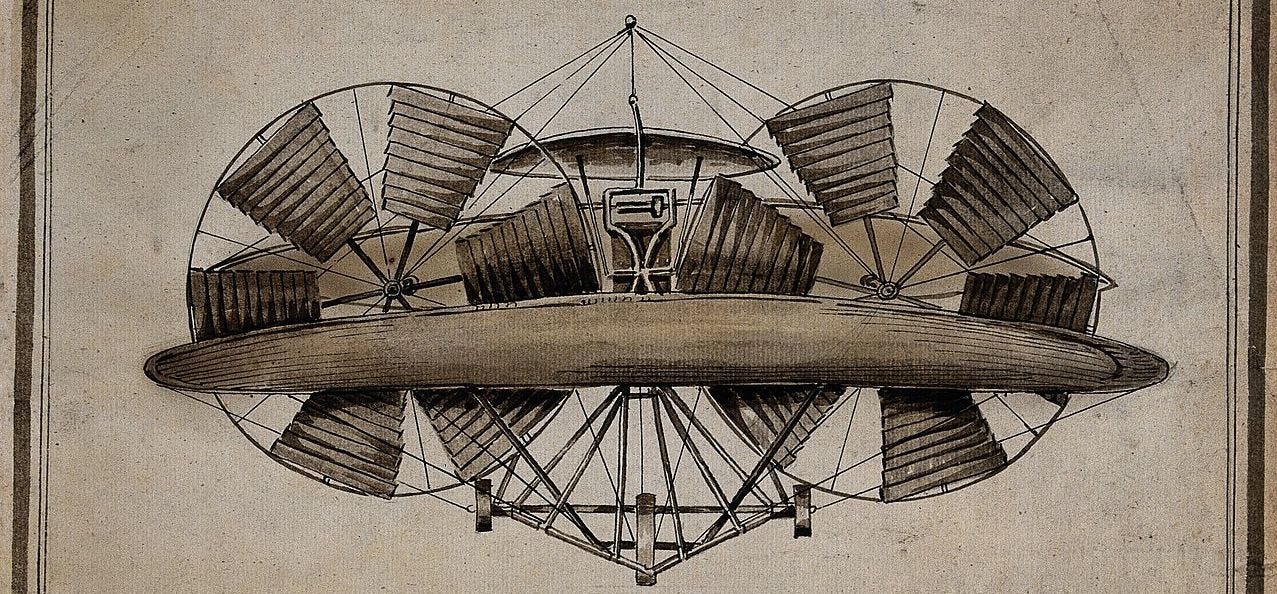

The implication of such scientific theories was that innovation and technology were required to bring about desired social progress. Enter the telegraph, the telephone, radio, steam-driven vehicles, flying machines, and even—imagine this—electric vehicles fueled by nature-power electrical stations. “Popular and technical journals were full of plans to build electric boats and electric locomotives. Experts argued over whether electricity would become more economic than steam power. The future pictured in scientific romances was overwhelmingly electrical, with electricity generated in limitless amounts from wind, sun or water.” The namesake of Elon Musk’s electric-car company—Nikola Tesla—at the start of the 20th century envisioned a future of wireless electricity everywhere, too cheap to meter.

To name but a few of the Victorian innovations that resonate today as artfully described by Mr. Morus: Aerial steam carriages, airships, analytical engines (computers), automatic cash register, calculating engine, comptograph (printer), daguerreotype (camera), electric turnstile, electric locomotive, electromagnetic clock, fingerprinting, machine gun, magneto-electric machines, nitric acid cell (battery), petroleum-powered tricycle, phonograph, physiognotrace (a device to produce silhouette portraits), polyphase motor, printing telegraph, programmable punch cards, rotary electromagnetic engine, Ruhmkorff coil (an electric lamp), safety lamp, steam gun, steam ships, steam trains, telautomatics (self-acting wireless weapons to make war redundant), voltaic piles (another battery), wireless torpedoes, and countless other inventions that swelled patent offices.

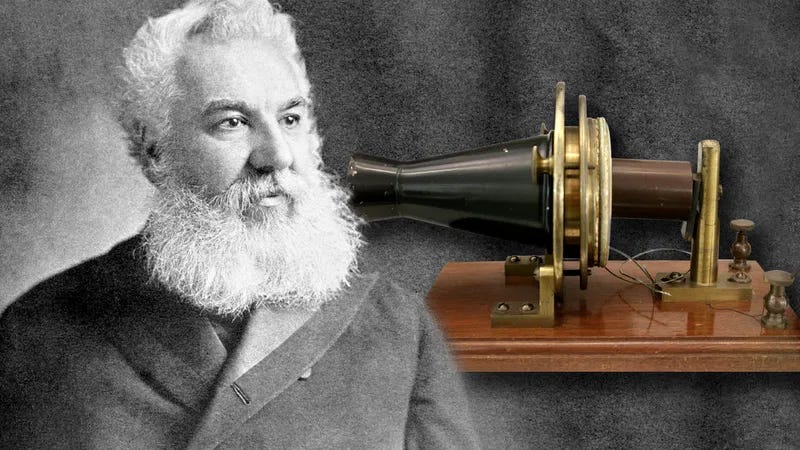

Alexander Graham Bell’s invention of the telephone in 1876 was especially fecund, generating endless spinoff technologies, such as telectroscopes—electrical devices for visual communication over long distances—think Facetime, Zoom, or Skype. Telectroscopes, along with wireless telegraphy, were also employed in science fiction stories to imagine communicating with people inhabiting other worlds, because of course the idea of colonizing Mars didn’t begin with Mr. Musk. And, just like “we make our futures out of bits and pieces of our present, and we see it as made by science and technology,” so too did the Victorians who, Mr. Morus notes, pioneered another innovation still in use today: “They shared a common cause in making their expertise count in the corridors of political power so that they could actively engage in future-making.” Example: mechanical calculators, such as Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine, were envisioned to be vital instruments of an ever-growing imperial bureaucracy, as way of keeping demographic tabs on citizens near and far.

An editorial cartoon in the popular publication Punch, however, places Victorian progress in a cultural context completely out of sync with our own when it portrays successful parents chatting via a telectroscope in real time with their children in far off lands…that are British colonies. Indeed, one vision of instant communication that electricity provided through the telephone and wireless telegraphy was “new ways of keeping the Empire together—giving the centre of imperial power tools that would prove vital for keeping the peripheries under control…an all-seeing eye for the state.”

As well, the Victorian heroes of Mr. Morus’s book were overwhelmingly middle class and, predictably for the era, male (not to mention white). Imposing order on nature’s entropy required discipline, and to the Victorians “the possession of disciplined minds was what was supposed to be the difference between men and women. Men could be trusted to keep themselves under control while women were at the mercy of their uncontrollable bodies.”

By way of example, Morus cites Samuel Smiles’ wildly popular work, Self-Help, in which women are conspicuous by their absence. “As far as Smiles, his readers and the men they were urged to emulate were concerned, individual self-improvement was an entirely masculine affair. The notion that a woman might be a role model, or even a potential reader, would have simply been inconceivable. Men of science were clear that their science was a man’s domain. It required a cast of character that was distinctively masculine.”

It is natural for all generations to think they live in special times. And maybe they do. But with the first two decades of the 21st century behind us and looking back to how we got here, the case that it was the Victorians who got us here more than any other cluster of precursors is one well made in this riveting account of the world we inherited, even while leaving behind the prejudices of the past that will, in the fullness of time, generate even more progress, both technological and moral.

###

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the host of The Michael Shermer Show, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His new book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational.

Thanks for the review, Michael. As you mention Punch cartoons, you might enjoy this one from 1906 which seems to foresee a cultural context more in sync with our own in its depiction of the isolating quality of mobile phone use: https://magazine.punch.co.uk/image/I0000uf21lEwHGH4