Psychling

Lessons learned in business, sports, and life from the Great American Bike Race, and what this tells us about how lives turn out—it's massively contingent

How do lives turn out as they do? Is it genes or environment or some combination thereof? It is both, of course, but there is something more at work, and that is contingency—a conjuncture of events occurring without design. Contingencies are the sometimes small, apparently insignificant, and usually unexpected events of life that have outsized effects. You zigged instead of zagged. You went left instead of right. You went to the party instead of staying home. You took this job instead of that job. You married this person instead of that person.

After the fact, with the hindsight bias fully engaged, it seems so obvious and postdictable as to how and why one’s life unfolded as it did. But at the decision tree bifurcation point—the garden of forking paths, as Jorge Luis Borges titled his short novel—who knows what is to come next? Such stories of apparently random and unpredictable events are typically presented as rare and exceptional, but in fact I suspect they are so common as to make contingency a force in life as potent as genes and environment, and thus worthy of consideration not only by social scientists, but by biographers, autobiographers, memoirists, and historians.

Case in point: a long time ago in a life far far away…

In 1979 I completed a graduate degree program in experimental psychology at California State University, Fullerton, with the goal of becoming a college professor, the only career I aspired to (after archetypal childhood dreams of astronaut and professional baseball player). But the job market was grim that year and I was unable to land a regular teaching position (and I needed full-time work), so I meandered over to the placement office where I found a job opening for an editor (I told them I enjoy writing) at a trade magazine called Bicycle Dealer Showcase.

My first assignment was to interview a cyclist named John Marino, who had just ridden his bike from Los Angeles to New York in a Guinness Book record time of 12 days, 3 hours, and 41 minutes. I was gripped by his adventurous story, and as he lived only five miles from me I bought a bike and started riding with John, first 25 miles, then 50, then centuries, then double centuries. The next year I rode my bike from Seattle City Hall to San Diego City Hall in 7 days, 15 hours, in part as a fundraiser for the Cure Paralysis Foundation (my college sweetheart, Maureen Hannon, was paralyzed in an automobile accident and I wanted to do something—anything—to help). Motivated to improve myself and my cycling performance, in 1981 I repeated the ride, this time covering the 1,386 miles in 4 days, 14 hours, 15 minutes, averaging 301.3 miles per day. (During this time I kept one foot in academia teaching Psychology 101 nights at Glendale College.)

The author with his father, Richard Shermer, in 1981 at San Diego City Hall.

Later that year, at an industry bike show in Cleveland, I had breakfast with John Marino and the Olympic cyclist John Howard, who wanted to break Marino’s transcontinental record (along with the Land Speed Record on a bike of 152 MPH drafting behind a race car, and win the Hawaii Ironman Triathlon, both of which he accomplished). Marino told us of his dream from years before of one-day racing across America against other cyclists, and so that breakfast morphed into a race-planning meeting, which included Marino placing a call to the man who had just broke his transcontinental record—Lon Haldeman—who did so on the back end of a double crossing from New York to Los Angeles back to New York.

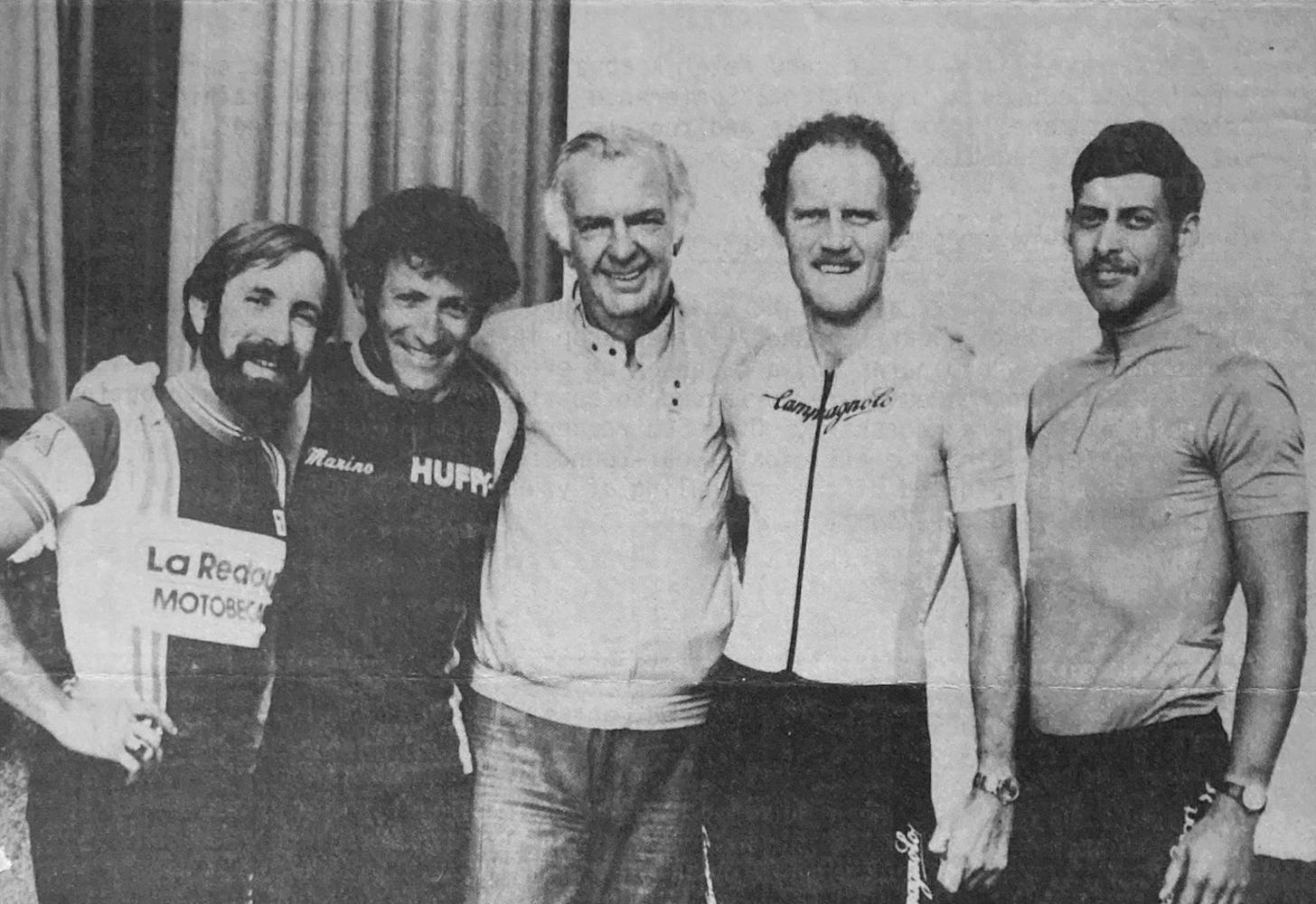

L-R: John Howard, John Marino, Michael Shermer, Lon Haldeman, in San Francisco.

Marino titled it the Great American Bike Race (GABR), and he had a powerful Hollywood agent named Jerrold Kushnick (who represented Jay Leno and other celebrities) who had procured sponsorships and media coverage of John’s transcontinental rides. Later that summer the four of us—Marino, Howard, Haldeman, and myself—met in San Francisco at the CitySports magazine BikeFest (see photo above) where we outlined the ground rules of the competition and made a pact that no matter what happened regarding sponsors and television, we would race. If necessary, and as a last resort, we would use our own money to sponsor ourselves, the winner getting a pat on the back from the other three. That said, of course we all hoped that the race would pay for itself, and possibly even be parlayed into a source of income above expenses. But it was Kushnick who changed those hopes into expectations, and ultimately almost shattered our dreams entirely.

L-R: Michael Shermer, John Marino, Jerrold Kushnick, John Howard, Lon Haldeman

We met with Kushnick in September to discuss the race, to be run August of the following year, 1982. In the interim, Kushnick explained that he planned to land a television contract with a major network who would pay upward of $100,000 for the rights. Then he would procure a major sponsor in the range of $250,000 to $500,000. Minor sponsors would follow, adding perhaps another $50,000 to $100,000. Additional moneys would come from personal product endorsements, commemorative items, posters, magazine articles, speaking engagements, and books. All told there should have been little difficulty, we were assured in a manner only a Hollywood agent could, in raising a million dollars, to be split among us four racers and the talent agency.

To his credit, Kushnick started off with a bang. By the beginning of 1982 he had secured a written contract with ABC, the race to be covered in two segments of Wide World of Sports, the network’s flagship show that was expanding its programming to also cover the Hawaii Ironman Triathlon and the Iditarod Sled Dog Race. The rights fees were considerably less than the $100,000 Kushnick anticipated, but $25,000 was a start, and once you have network television the sponsors are supposed to come knocking at your door.

Initially, we thought that we should set up a contract among the five of us to solidify the specifics of percentages, ownership of the event, incorporation, tax liability, and so on. But Kushnick said that would not be necessary. “Trust me, I’ll handle everything,” were his memorable words. His rationale was that if we incorporated together under a legal contract then we could be accused of collusion in a race that was supposed to be unbiased and fair. He told us that ABC was reluctant to sign a contract to cover a sporting event owned by the competitors (which was not true, since they did so in subsequent years). So no contract was signed. We were all as good as our word—the value of which would come to light soon enough.

As the months rolled by, our mileages piled up along with our personal debts. Kushnick kept assuring us that it would not be long before big contracts started rolling into his posh Sunset Boulevard office. But nearly every scheduled meeting between us was delayed, postponed, or canceled. When we did meet we heard the usual assurance: “Trust me, I’ll handle everything. Just keep training.” And train we did. Spring turned into summer and the mileages rose accordingly—400 miles a week, 500 miles a week, 600 miles a week. This was going to be a record-setting race. The four of us were in the prime condition of our lives. We had all devoted the year to monomaniacally pursuing our goal. It would surely all come together.

Then we got The Call. Four weeks before the race, Kushnick wanted to see us in his office for a Very Important Meeting. This would be the major sponsor, we hoped. Kushnick had been talking to the soft drink company Shasta. Surely they had finally come through with the figures for which Kushnick was holding out—$250,000. Nope. Shasta turned him down. In fact, every single company contacted—with the exception of Igloo, which donated a couple of ice chests per rider—answered the call in the negative. (Later, after the race, we discovered what really happened was that Shasta countered with an offer for about half that amount, which Kushnick turned down in hopes of “calling their bluff.” They were not playing poker, however. In a last ditch effort with a week to go, Kushnick called them back to accept their counter-offer, but it was too late. They declined.)

“My recommendation, boys,” Kushnick informed us at the meeting, “is to cancel the race until next year. Considering our financial state, ABC is getting cold feet, and they’d just as soon terminate the contract and renegotiate later for the next year.” We couldn’t believe it. We sat there with our jaws on the floor. All those miles and all that planning would go down the drain. Kushnick wanted to bow out gracefully. “Absolutely not,” was Marino’s rejoinder, speaking for the rest of us. We had made a pact to go no matter what, so we were going to race come hell or high water, and both had come.

Then a minor miracle happened. Days before the race, a friend of Marino’s named Don Milam took it upon himself to make some phone calls to a few corporate contacts he had, one in particular at Anheuser-Busch. Unbelievably, 48 hours before the race, Bud Light became the official sponsor of the Great American Bike Race. A fee of $25,000 bought them name sponsorship plus logos anywhere they could fit them on our motorhomes, jerseys and shorts. The night before the race a seamstress affixed Bud Light logos to our cycling kits!

Despite the last-minute infusion of money, Kushnick told us that he needed most of it to cover his expenses (he had receipts) and that if we wanted to race each of us had to cut him a check for $10,000, minus $2,000 he would give us from Bud Light’s sponsorship. Interesting accounting, but we were desperate to race so we ponied up the cash.

Just when it looked like we would finally get on with actually racing our bicycles, Kushnick had one final request that he floated at dinner a few nights before the start. I will never forget it. “Guys, I want you to understand that this event is a television program—an entertainment show. If it is not exciting, ABC will not return. Now, what I want you to do is keep the race together until about Ohio or West Virginia. I don't want anyone running away with the race. If it spreads out too much, it won't be interesting. Stay within a few miles of each other. Remember, this is television!”

The three of us looked around the table at each other (Haldeman was driving out from Illinois) and wondered if he was serious. The way he said it made it sound like we had to do this…or else. I remember thinking to myself, “this guy doesn’t know John Howard, who is so über competitive he wouldn’t ‘keep the race together’ to the first city-limit sign!” And none of us really knew how Haldeman would react. It was utterly preposterous, but we nodded politely and promised that we would be good boys. After Kushnick left, we decided that we would all just ride as fast as we could and let the chips fall where they may.

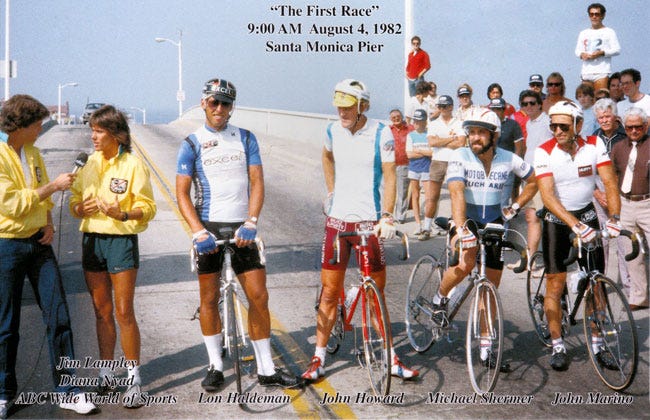

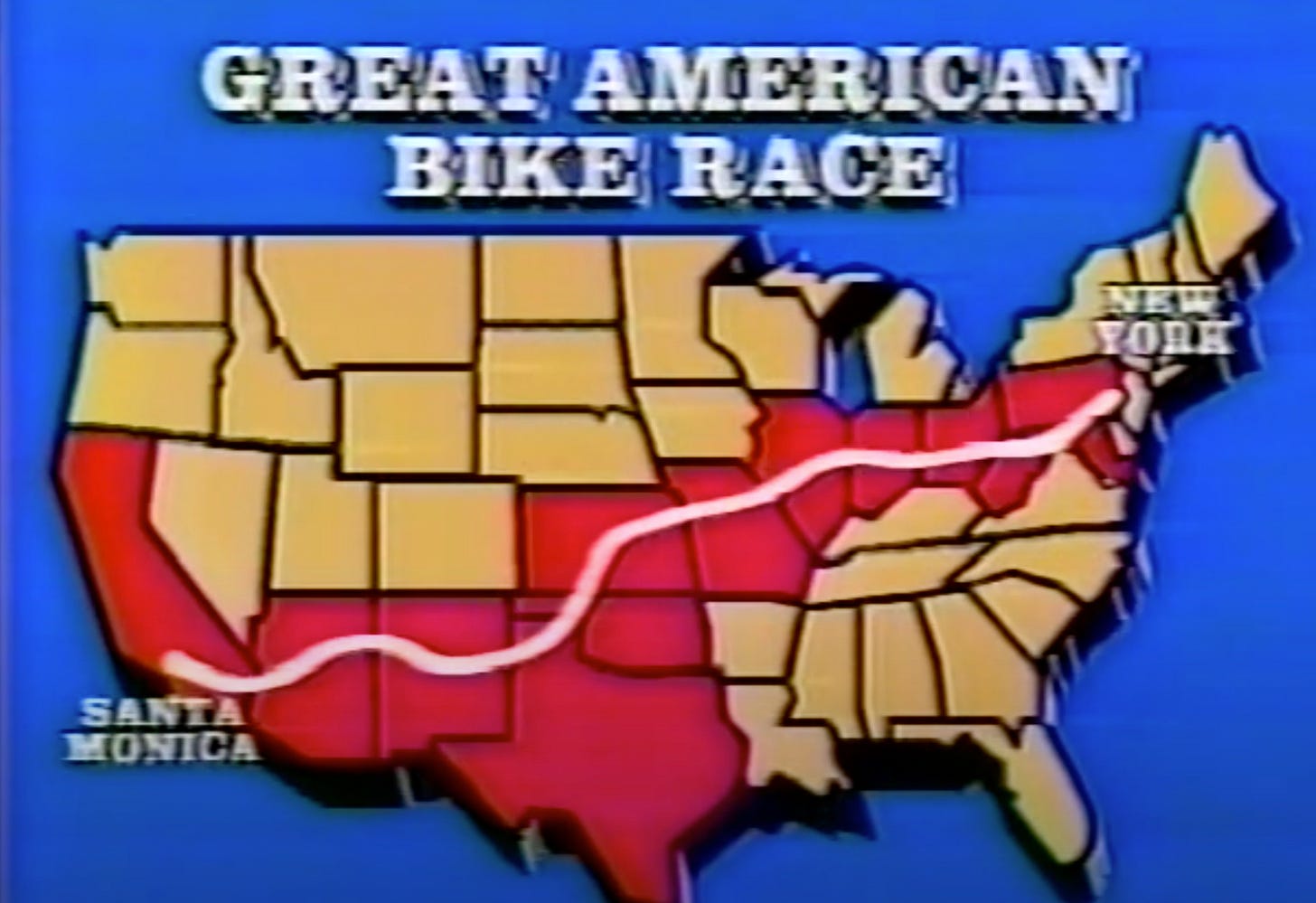

At 10:06 a.m. PDT, on Wednesday, August 4, 1982, the agonies and glories of the world's longest and cruelest bicycle race in history began. Geographically, it would be a race from the pier in Santa Monica to the Empire State Building in New York City. Psychologically, it was a battle of wills to see who could suffer without yielding, who could endure the most pain, and who could sleep the least.

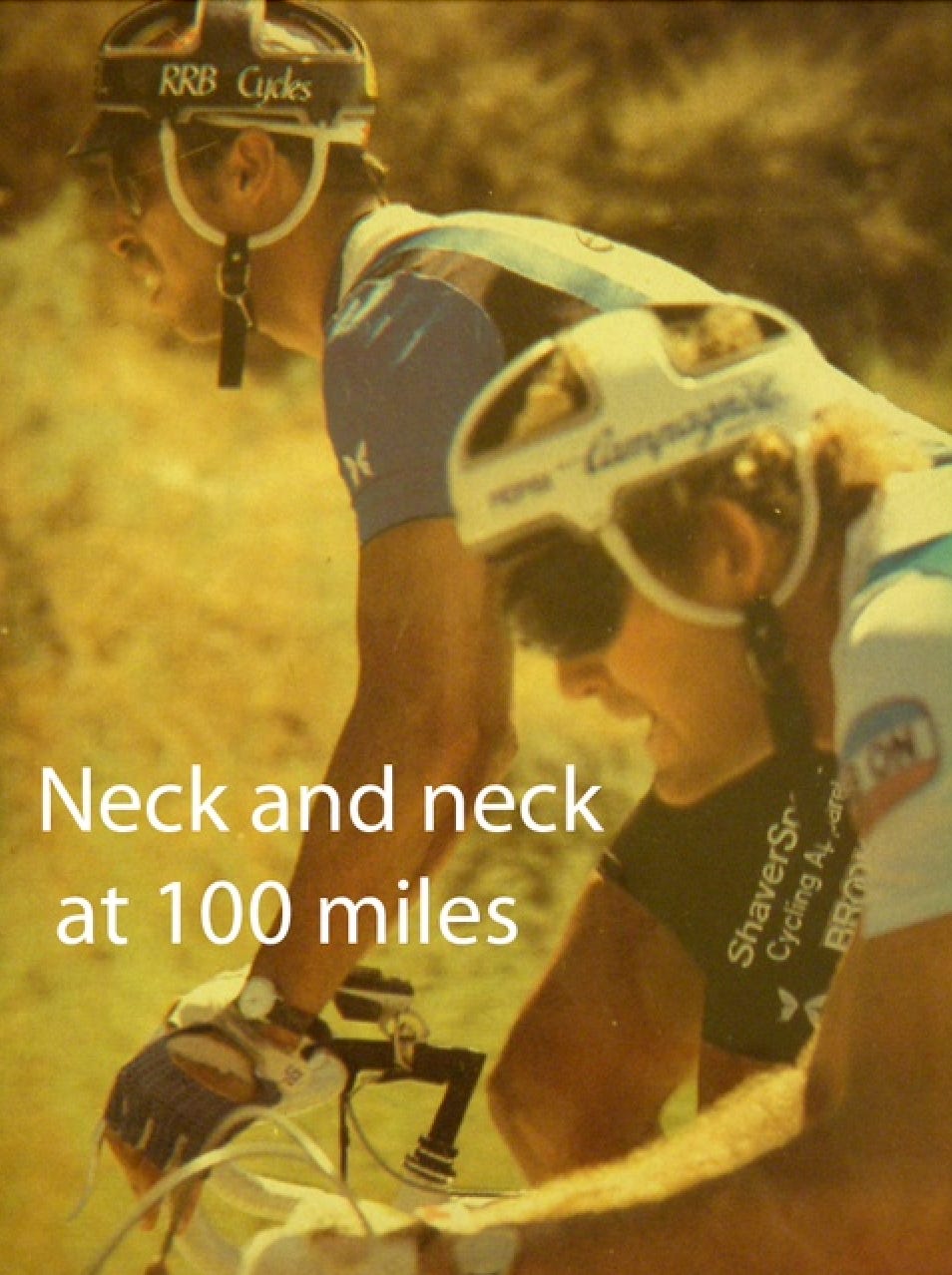

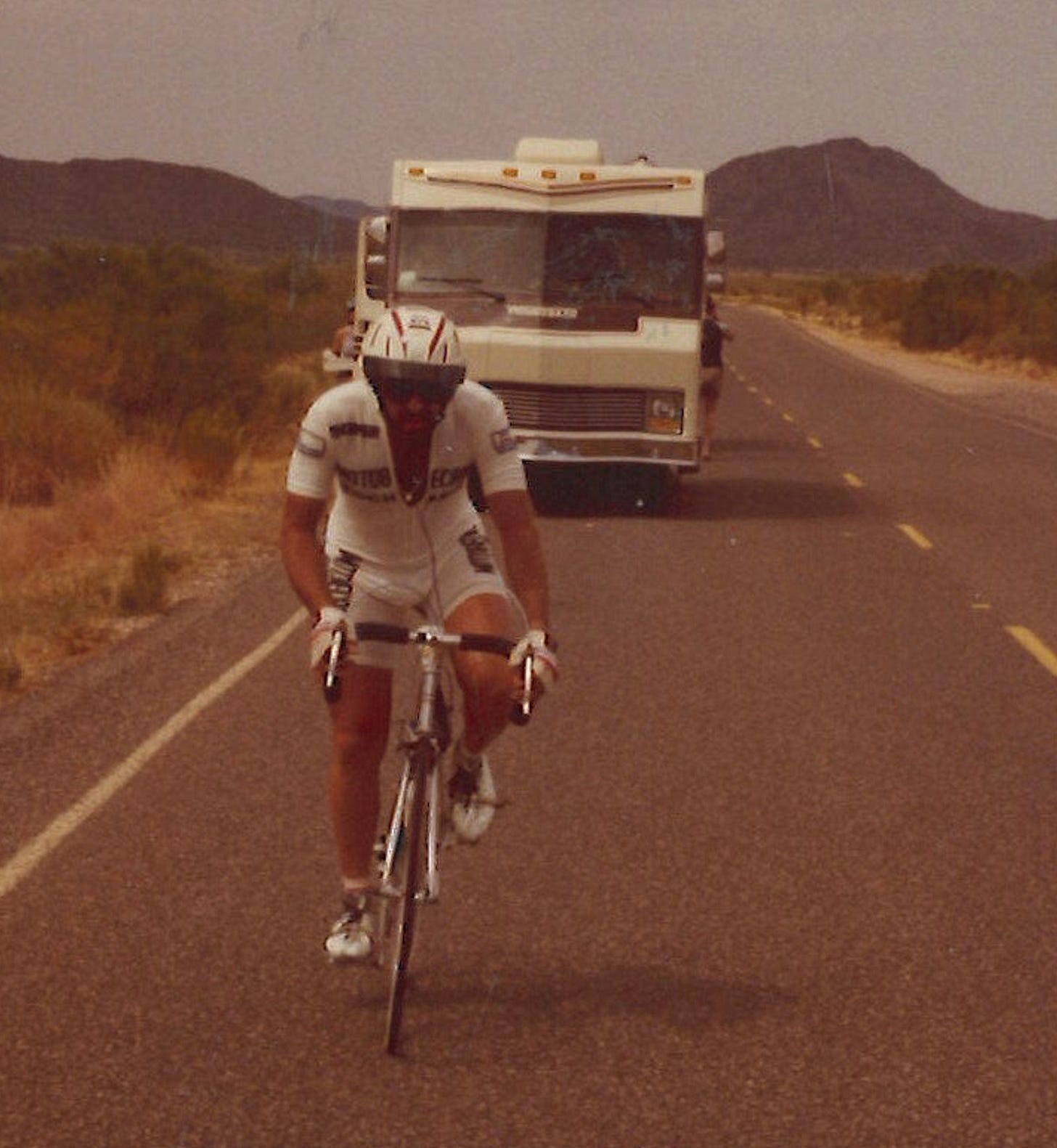

The four of us rode out of Los Angeles together until San Timiteo Canyon Road approaching the 75-mile mark near Beaumont, on the edge of the California dessert and its unforgiving heat in excess of 100 degrees. Having never covered this 2,976-mile course, neither John Howard nor I had any particular strategy. Marino’s philosophy, as explained by a sign in his motor home, was “Remember the tortoise and the hare.” Haldeman, whose demeanor was quiet and unassuming before the race, had a strategy that became obvious from the beginning. He set an incredibly grueling pace that left all of us, including the hare John Howard (see photo below), in the dust. We averaged 16.2 MPH through the parade start, but Lon accelerated to 23-24 MPH on the open desert roads as the temperatures began to climb.

As fast as Lon pulled out in front, Marino fell behind with numerous bike problems, including flat tires and a defective crank arm. By the second checkpoint at the 114-mile mark, Haldeman was 30 seconds ahead of Howard, 7.5 minutes in front of me, and 12.5 minutes over Marino. Despite the fact that the thermometer had climbed to 115 degrees, Haldeman's average speed had increased to an almost unbelievable 22.5 miles per hour. (Photo below shows John Howard on the long climb to Desert Center.)

The second part of Lon's strategy came with sunrise on day two. Haldeman was somewhere up the road. Marino's problems continued and he fell further behind. The excessive heat found Howard puking his guts out on the side of the road at the Arizona border, where I passed him near midnight to move into second place. At 3:00 a.m., I was about two hours behind Lon and planned on sleeping only three hours. Since Lon would surely sleep four to five hours, I mistakenly assumed, I would catch him in the morning. However, I awoke to the news that I was now four and a half hours behind Lon. Haldeman rode through the night.

While Lon cruised steadily in front, seemingly tireless, the race official, Bob Hustwit, reported that Howard “looked and felt wasted” and had his doubts as to whether John would be able to continue into the second day. He recommended a physical examination “and the possibility of insisting that he withdraw for medical reasons.” As for the other John, Hustwit reported that “Marino had hit his first wall.”

The next morning found all of us climbing the steep nine-percent grade up Yarnell Hill to Prescott, Arizona, elevation 7,000 feet. Enthusiasts from the frontier gold and silver mining town had placed a “GOOD LUCK MARINO” sign on one of the highway markers coming into the city, which gave the beleaguered cyclist a momentary lift. Lon had finally bedded down around 8:00 a.m., but he was apparently bothered by a lawnmower that drove him back on to his bike. Howard was checked by the race doctor, who said his pulse had slowed to 55 but that he could continue the race. His appetite returned the afternoon of the second day, and as we climbed steadily toward Flagstaff, Hustwit reported that “Haldeman's physical condition was growing even stronger.”

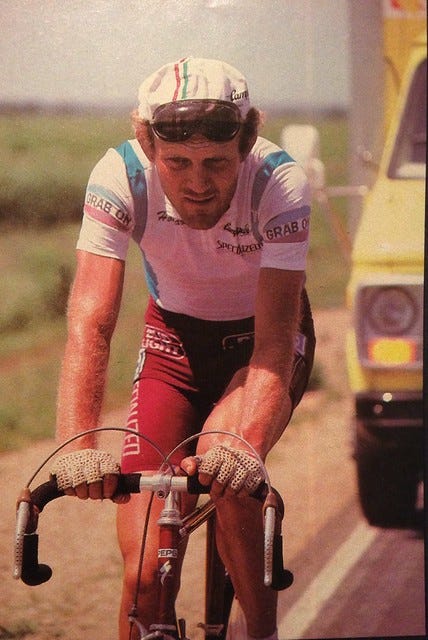

The author climbing up Oak Creek Canyon from Sedona to Flagstaff, Arizona, with Sony Walkman earphones blasting classic rock

I was suffering from a condition called “hot foot”, which is exactly what it sounds like, and as night approached I was bonking out, cycling jargon for running out of energy. As we stair-stepped our way through the high desert through the historic mining town of Jerome and the New Age mecca Sedona, Howard caught me just outside of Flagstaff, Arizona, and together we rode for a while along Interstate 40, discussing strategies on how to catch Lon who, after 587.8 miles was averaging 16.31 MPH, compared to Howard's and my 14.64 MPH. Again at 3:00 a.m. I bedded down for three hours, trying to pace myself and hoping Lon would eventually crack. This was a tactical error. Lon once again rode through the night, as did Howard, and I rose with the sun to find myself hours behind in third place.

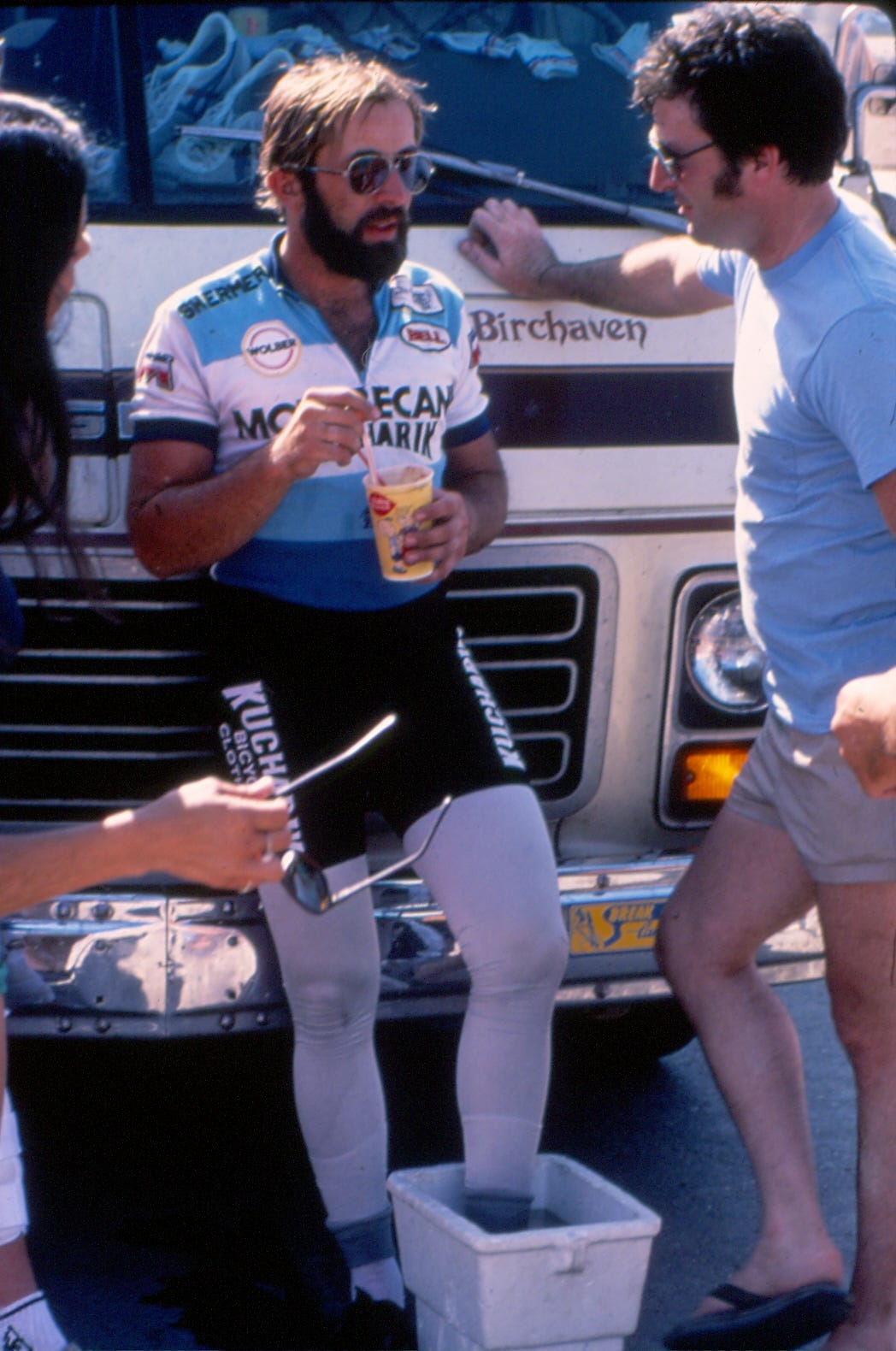

How to deal with hot foot: a bucket of ice water and a Dairy Queen Blizzard

Day Three. The race official's journal read:

Lon Haldeman's tremendous pace had everyone in awe. The doctor's report on Marino indicated that he had strained the medial side of his right knee and again had lapsed into a non-eating cycle. Shermer's spirits were up, with no signs of depression. Shermer's feet felt much better, as the foot pads seemed to have helped. Shermer expressed deep concern over the fact that he did not realize the enormity of the trek, and how long and demanding the race would actually become. Howard, who was on the verge of heatstroke 24 hours before, and on the verge of being removed from the race by the doctor, had made an amazing recovery and was now riding at almost full capacity. When asked about his sleeping pattern, Howard responded that he didn't want to sleep. His two requests were for new foot pads and baby food.

Meanwhile, Haldeman continued to pull away. Lon had slept the least (two hours versus Howard’s 3.5, my 6, and Marino’s 6.5) but was maintaining an average speed a full mile per hour faster than the rest of us. “Many wondered whether Haldeman could continue this amazing pace,” noted Hustwit, “or would the continued lack of sleep cause him to hit the wall?” We were hoping for the latter.

By the fourth day we had passed the continental divide and were approaching the Great Plains states of Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. Having never crossed the continental divide, I naively expected a dramatic drop-off in the geography and hoped for a long steep descent for many tens of miles. What I discovered was that in the southern United States the continental divide is very subtle. If a sign had not been posted on the side of the road, I never would have been aware that I had just crossed the highest point of that part of the continent.

The author, somewhere in New Mexico.

As we passed through the plains, endless acres of corn were spread out as far as the eye could see. Silos strategically placed every 10 miles marked the progress of the race and served as incremental goals. I would time myself between silos to see if I could improve my speed. Here is how Lon described the soul-crushing bleakness of this part of the race:

Not only was the middle third located 1,000 miles from the start or finish, there was nothing much to look forward to in the middle 1,000 miles. The short-term goal of crossing the desert and climbing the western mountains was over. The goal of the middle third was just another grain mill tower eleven miles straight ahead.

After over 1,000 miles of cycling, speed was no longer a factor. It was now just a matter of staying on the bike as long as possible. Since Lon seemed to be averaging approximately one MPH faster than me, in the course of a 21-hour riding day, that would amount to a 210-mile spread over a 10-day crossing. I would now have to make my move. I would need to go without sleep for nearly six consecutive days. Could it be done?

Being a research psychologist, I knew what the consequences of this decision would be. In classic sleep deprivation experiments, after only two days of sleeplessness, subjects begin to lose fine motor control in manual dexterity tasks and their thinking slows. After three days of sleep deprivation, hallucinations begin and things get weird. By day four, there is a definite loss of touch with reality. This was day five.

It was interesting, yet distressing, to watch these symptoms unfold before my eyes. While descending the nine mile stretch into Albuquerque, New Mexico on Interstate 40, for example, I “saw” Marino running alongside me. Approaching Indianapolis, Indiana, trees on the side of the road morphed into creatures leaning over to assault me. In Athens, Ohio, I visualized blotches of pavement as various creatures—dogs, lions, giraffes, and snakes. Clusters of mailboxes on the side of the road in the midwest shape-shifted into fans cheering me on. I was not the only one suffering these mental effects. As a Bicycling journalist covering the race reported:

Three days into the race, John Howard was overcome by the noonday sun, a huge searing ball of fire that broiled his back. Suddenly he slammed on the brakes and screamed, ‘Look out for the brick wall!’ Aghast, his crew members leaned out the support crew window. They knew there were no brick walls on Highway 89.

I never knew what the expression “loss of touch with reality” meant until I reached Decatur, Illinois. Riding along the two-lane highway my crew captain, Dan Cunningham, pulled alongside in the mechanic's van and inquired if I needed anything to eat. “Who are you?” I demanded. “Where am I, California?” Composed but inwardly shaken, Dan explained that they were my support crew for this race to New York and that I was in Illinois. “Oh, all right,” I responded as I continued to pedal down the road.

At the Illinois border Lon Haldeman had accumulated an insurmountable lead of 175 miles between himself and John Howard, and 195 miles over me. John Marino was suffering such excruciating saddle boils that no matter how he sat on the seat, or how many different saddles he tried, pain wracked his body. John's pace dropped dramatically. More importantly, his time off the bike increased—a sign of the end. Hustwit’s race official log notes:

As his saddle sores had worsened, Marino’s crew had to improvise and devise a seat that would ease his pain and allow him to continue in the race. A number of new bicycle seats were created by Marino’s crew to attempt to alleviate his seat problems. Using an awl, they cut out the center of his bicycle seat and stuffed it with an overpacked soft-egg crate padding. Another improvisation was the sling seat, which was made from a spare handlebar placed in the rear of the bicycle seat for additional support. Each new seat temporarily reduced the pain, but nothing eliminated the pain which became more severe and eventually consumed Marino and his quest for victory.

For me, the thought of trying to chase down Lon became increasingly depressing. I knew what 200 miles meant—over 12 hours of riding time. Even with five days of little or no sleep, I was unable to close the gap to within striking distance. My final hopes were dashed coming out of Athens, Ohio. While descending a hill at nearly 30 MPH I fell asleep and collided with the guardrail separating the road from the cliff below. While only a few bruises and scrapes were incurred, my crew determined it was time for a long sleep break.

With first place virtually locked up by Lon and out of my reach, I focused my energies on reeling in Howard, who was within striking distance. John had narrowly escaped my clutches in Springfield, Illinois, where I was closing in while he was sleeping. The police escort that accompanied each of us across Illinois informed me that he had just spoken to another officer who was with John and that Howard was sound asleep in downtown Springfield. Now only 15 miles out of town, I picked up the pace. As I was nearing the city limits, however, Howard's crew informed him of my approach and he immediately got back on his bike and went flying down the highway. My crew then plastered a cycling magazine picture of Howard on the rear window of our motorhome with a hand-scrawled caption: “John Howard: Wanted Dead or Alive.”

By concentrating on catching Howard I was able to gain some ground on Haldeman, but the distance was so great that it would now take an act of God or nature to stop him. The distance between Howard and myself fluctuated the rest of the way to New York, as John maintained dim hopes of Lon slowing or collapsing. By day seven the doctor's report on Haldeman indicated:

he had eaten a whole cheese and sausage pizza for lunch. Haldeman, for the first time, was showing signs of weariness, though he was still taking the hills, and his strength and stamina were incredible. When asked for an autograph at a rest stop, Haldeman was barely able to sign his name.

Howard, though unable to catch Haldeman, had regained his old self-confidence and “His appetite was ravenous,” the doctor scribbled, “and when food was offered to him from the support vehicle he would grab at the foods he wanted with animal-like lunges.” Marino’s tortoise and hare philosophy was faltering and he was now 342 miles behind Lon. Noted the race official, “Marino hadn't seen a trace of Shermer for days, and the emotional stress was showing. He felt as though he were chasing ‘ghost riders’.” An excerpt from the race doctor’s report approximately 2,000 miles into the race reveals the raw nature of what we were experiencing:

The lack of sleep is taking its toll on Shermer. Many parts of his body are growing numb, including his feet and palms, and Shermer had difficulty walking when he was off the bicycle. Even tasks such as talking became a tremendous burden. Shermer found himself dozing off while on the road. His seat and knees still hurt, but his one driving concern was to pass Howard.

Although Haldeman looked tired, he claimed to feel fine and supported this statement by maintaining a 15-MPH pace over any terrain he crossed. Haldeman was extremely well hydrated. He continued to drink his mixture of milk, instant breakfast, and honey and ate cheeseburgers and pizzas.

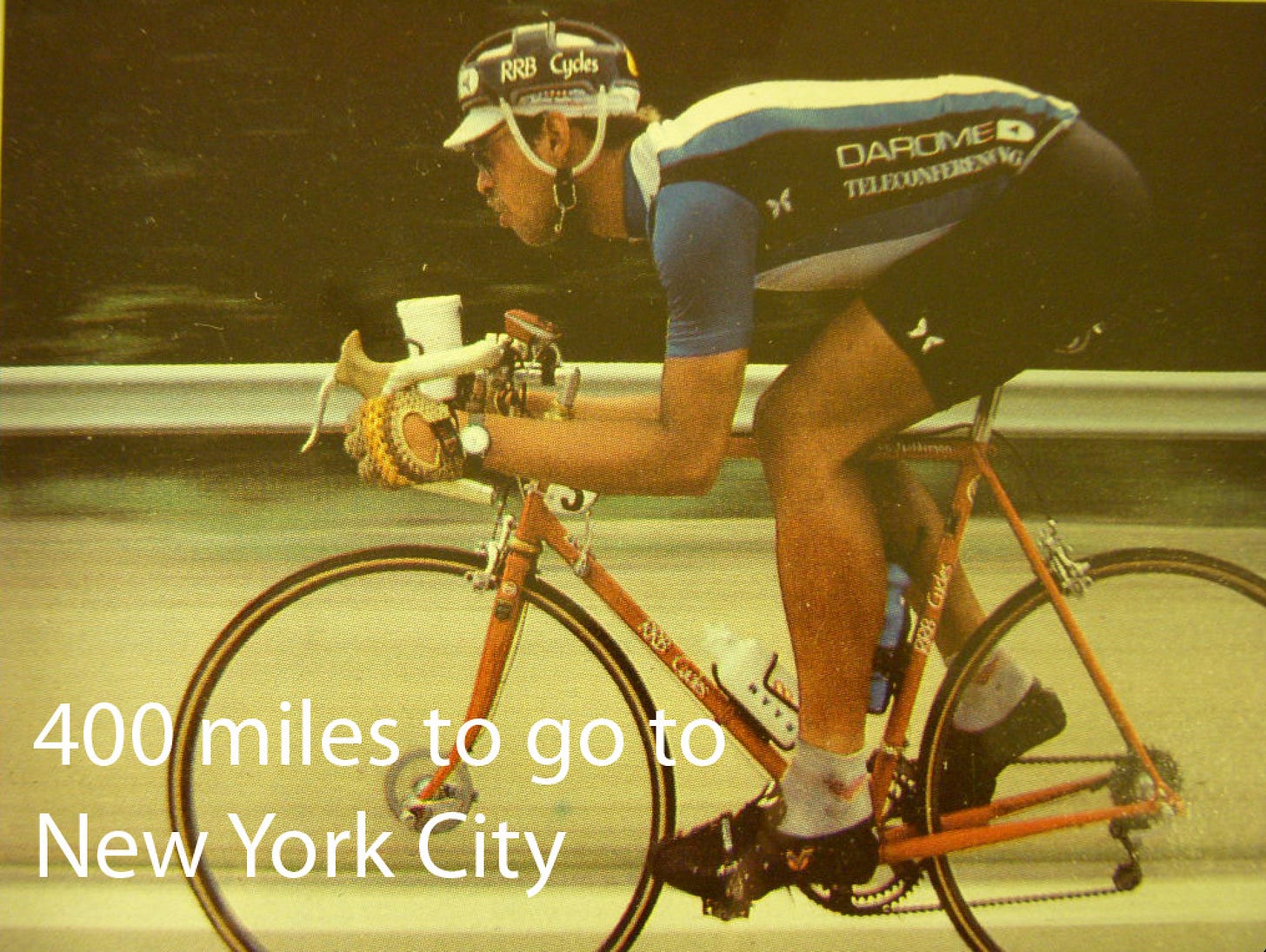

With less than 300 miles to go before reaching the Empire State Building, the news flashed back to me and my crew as we passed through West Virginia that Lon Haldeman had just won the race in a record time of 9 days, 20 hours, and 2 minutes. He was the winner of the first transcontinental bike race.

Jim Lampley, the ABC commentator from start to finish for Wide World of Sports, confessed that this was the most emotionally moving athletic event he had ever covered (see photo below). The race official's log was dramatic: “Film crews, commentators, and the members of the command crew gave way to their emotions and grown men cried as a tribute to a young man who had done the impossible, demonstrating the unbelievable capabilities of the trained human body.” Lon was presented with a trophy from Miss Bud Light, after which his support crew escorted him to his hotel room where he disappeared into alpha land of deep sleep.

Fifteen hours later, in a semi-hypnotic state, John Howard crossed over the George Washington Bridge onto Manhattan Island. “He appeared to be dozing off,” race official Hustwit reported. “His crew members shouted at him. Then Howard woke up, and, apparently not realizing where he was, took off in a sprint for the finish line, missing the appropriate turns and accelerating to over 30 MPH.” John later explained that he thought he was in a road race with a pack of riders and it was the final sprint for the finish. Howard then made his way through the clogged streets of Manhattan and finished in a time of 10 days, 10 hours, and 59 minutes (seen here with Diana Nyad). He went to his hotel and was not heard from again for two days.

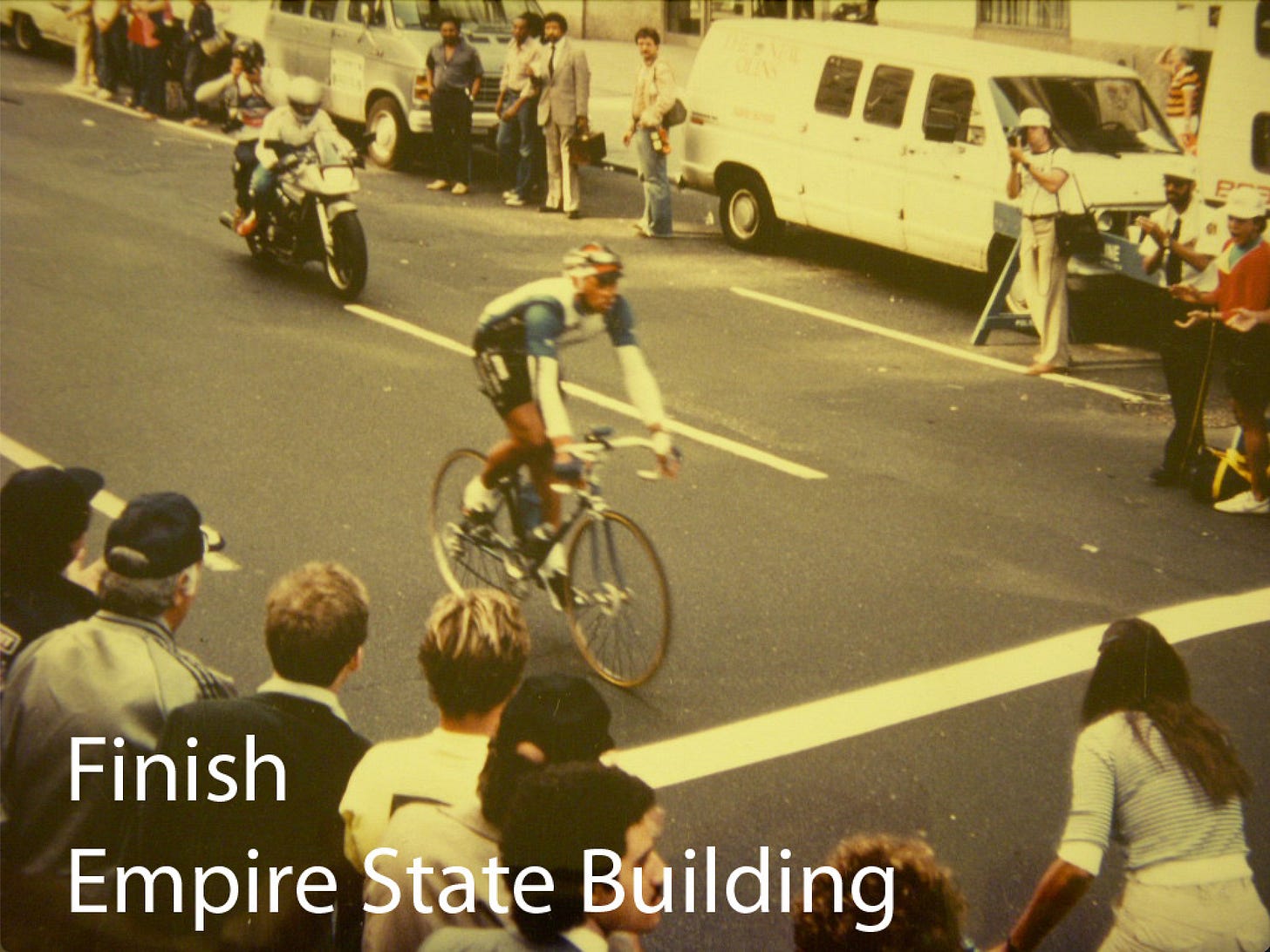

Early the next morning I experienced a cloudless sunrise over the matchless skyline of Manhattan. The Empire State Building, and the physical representation of what I had been visualizing for over 10 days, came into focus. Never truly knowing whether I would make it or not, I was finally in New York! I made the turn onto 5th Avenue and down to the Empire State Building where I was greeted by a crowd of people that included my parents. (Photos below.) An emotional ABC commentator Diana Nyad, who not long before had swum around this island, greeted me with her infectious energy. With a time of 10 days, 19 hours, 54 minutes, I had achieved my goal of breaking Lon’s previous transcontinental record. It was at that time the greatest moment of my life.

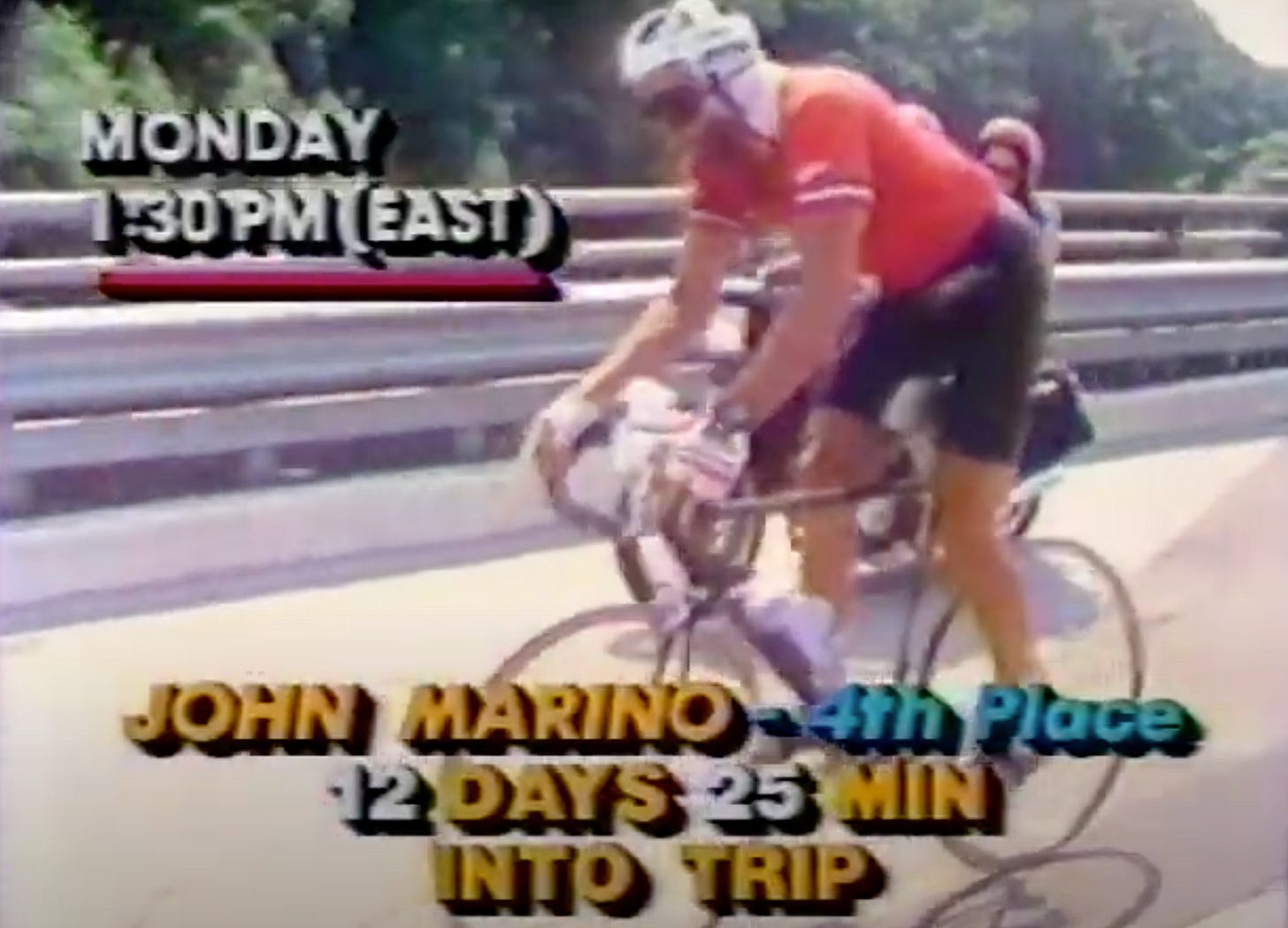

The fourth and final finisher, John Marino, almost wasn’t. On Day Nine, the race doctor reported that “Marino was nearing his threshold and must stop to sleep soon or face total collapse. He advised that he was seeing double images, and that he was beginning to hallucinate, that his bicycle was rising off the ground into the air.” The officials were not the only ones thinking of John's early demise. Marino himself faced the temptation at least twice, both times for which his wife Joni gave him the support he needed to continue. He pushed on, and as the race log indicated, crossed the finish line in 12 days, 7 hours, and 37 minutes:

Monday, August 16, 1982, must have been one of the longest and most difficult days of John Marino's life. He had felt the final strains of the transcontinental ride three times before, but never with the pressure of knowing that thousands of people were awaiting his arrival. He had considered quitting more than once, as he felt that he was prolonging the race unnecessarily and delaying the return home of the other riders and support crews.

A massive crowd of people was on hand to greet John, including his mother and two sisters who had also flown in for the finish. Relieved that the ordeal was finally over, John was genuinely surprised at the reception, blurting out “look at all the people!” He then reached deep to summon a final twist of humor amidst the agony when Diana Nyad (below) asked him what hurt the most. “My hands, my feet, and my rear end...but not in that order!” What would he like to do now? Nyad queried. “I'm going to have my annual beer... maybe three.”

Like the rest of us, John soon headed for the hotel, only to be reminded of the realities of what we had all left behind in Kushnick’s office, so poignantly captured by journalist Michael McRae for his account of the race in Outside magazine:

Unshaven and sweaty, he walked up to the desk, clacking in his racing cleats. The desk clerk hardly looked up from his computer terminal. ‘How would you like to pay for this, Mr. Marino?’ he asked. There was a slight tremor in Marino's hand as he presented his credit card.

To that day, and to the extent that the sport of ultra-marathon cycling had been explored, the four of us had pushed beyond the known limits of human endurance.

Coda

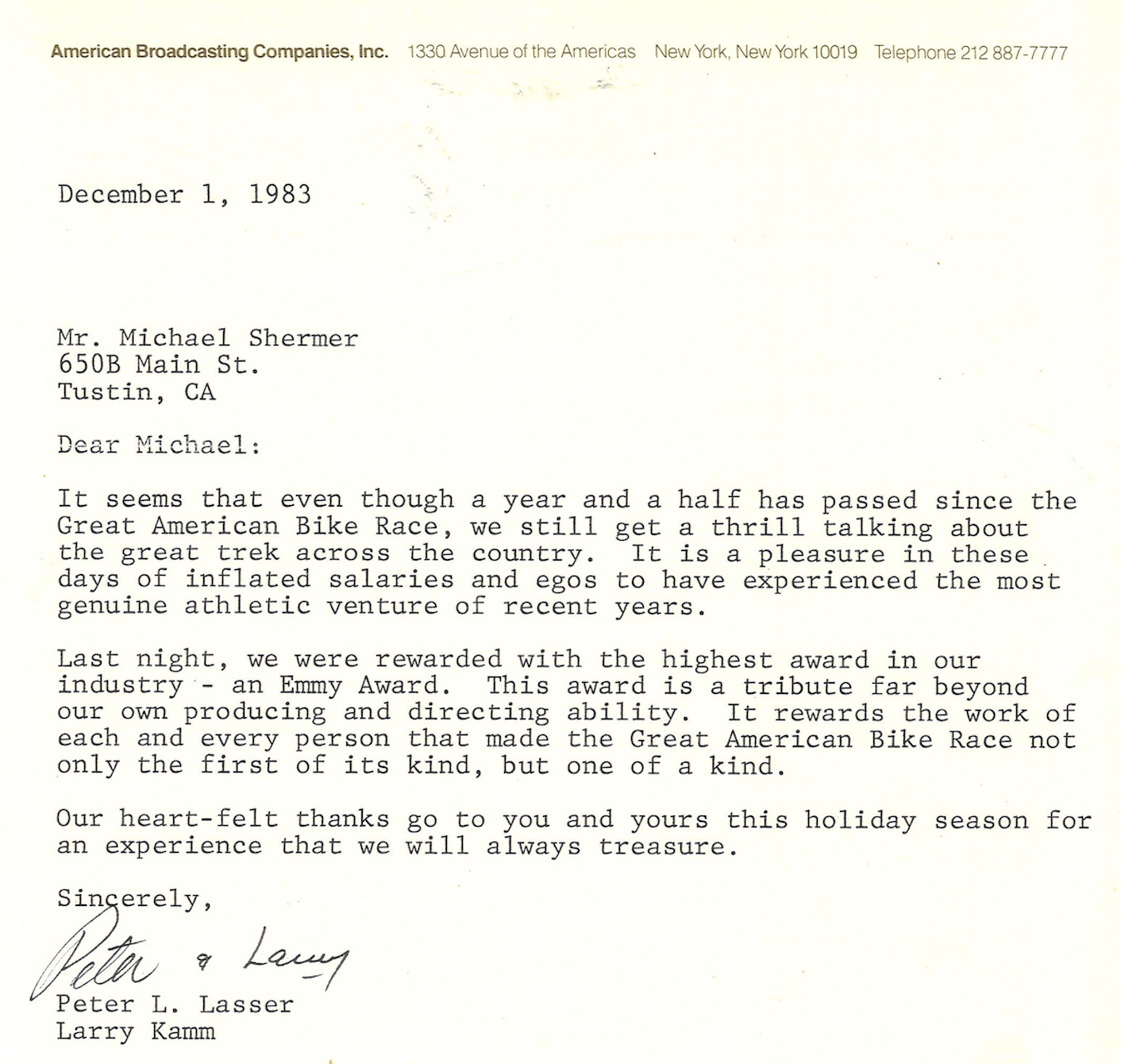

In the Spring of 1983 ABC aired its two-part Wide World of Sports special on the race, garnering an Emmy Award for best sports programming of the year for Executive Producer Roone Arledge and Directors Peter Lasser and Larry Kamm (see letter below). You can watch the show here here and here (in 3 parts).

The network executive who contracted with our agent for the Great American Bike Race wanted to cover the race again…but with one proviso: going forward they wanted nothing whatsoever to do with Jerrold Kushnick, who had apparently alienated them so thoroughly that they felt it necessary to give us an ultimatum. Young, naïve, and inexperienced, we didn’t know what to do, so we confronted Kushnick directly with the problem, quoting verbatim what the ABC executive told us. Far from being embarrassed, however, Kushnick informed us that, in fact, he had incorporated “Great American Bike Race” in his name, so we had no choice but to continue our relationship with him. We went back to the ABC executive with our dilemma, and I’ll never forget his response: “Fellas, we don’t care what you call the race. We just want to film you racing your bikes across America. Just change the name.”

That is how the Great American Bike Race became the Race Across America, and 40 years later the four of us rode out with the start of RAAM, still going strong after all these years.

L-R: Lon Haldeman, John Howard, Michael Shermer, John Marino in 2021, the 40th anniversary of the Race Across America, née The Great American Bike Race.

As for Kushnick, personal tragedy haunted him and his wife Helen. One of their twin children died at age 3 from AIDS (contracted from a blood transfusion), one of the nation’s first pediatric victims. A few years after the bike race, Kushnick was diagnosed with colon cancer and died two years later. Helen took over the talent agency, negotiating Jay Leno’s replacement of Johnny Carson as the host of the Tonight Show, taking for herself the position of Executive Producer. Four months later NBC fired her and banned her from the studio lot after numerous run-ins with executives, temperamental paroxysms over production decisions, and booking practices that required exclusive access to choice guests (all of which is recounted in the bestselling book The Late Shift, by New York Times reporter Bill Carter, and even more dramatically in an HBO movie starring Kathy Bates as Helen Kushnick). But then, at age 51, Helen Kushnick succumbed to breast cancer. The entire tragic saga is thoughtfully recounted by Emily Yoffe here.

As for that ABC executive who took a gamble on the obscure sport of ultramarathon cycling, his name was Bob Iger, and he went on to become President of ABC television and then the CEO of The Walt Disney Company, during which he orchestrated the acquisition of Pixar, Marvel Entertainment, Lucasfilm, and 21st Century Fox, thereby increasing the market capitalization of the company from $48 billion to $257 billion.

To think that all of that began with a vision of four young men who wanted to race their bicycles across America. Who would ever have predicted it?

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, Executive Director of the Skeptics Society, and the host of The Michael Shermer Show. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His latest book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational. His next book is: Truth: What it is, How to Find it, Why it Matters, to be published in 2025.

What a fascinating story, full of thrills and suspense. And to complete it, with a villain trying to sabotage the endeavors of four heroic figures, with fate punishing the villain in the end, with the heroes surviving and flourishing. Also a story expertly told, with wonderful pictures. I knew Michael Shermer was a bicycling enthusiast, but never suspected that he had been such a remarkable athlete. I hope he remains aware of the insidious sarcopenia that threatens aging fitness buffs, attacking fast-switch cells especially in the legs.

A hell of a story, very well told by someone who was there. I was one of those bike riders who had his life shaped by the example of these guys.