Putin's Problem

The outlawry of war has forced tyrants to concoct excuses for invading other countries. How should we respond? Evidence shows that outcasting in the form of economic sanctions beats armed conflict

After amassing nearly 200,000 troops and war materiel along the Ukrainian border and coastline the past few weeks—itself a follow-up to the 2014 annexation of Crimea—the former KGB officer and now President-for-Life Vladimir Putin on Monday (February 21) officially announced his recognition of the “independence” of two separatist groups in the eastern regions of that sovereign nation. They are the Donetsk People’s Republic and the Luhansk People’s Republic (not to be confused with the People’s Republic of Donetsk and the People’s Republic of Luhansk). U.S. intelligence announced that Putin was planning on staging “false-flag” operations as an excuse to launch a full-scale “defense” by his “police forces” of these poor beleaguered peoples being threatened by the West.

Russian President Vladimir Putin enters the hall during the Russian Energy Week 2001 plenary meeting on October 13, 2021 in Moscow, Russia. (Photo by Mikhail Svetlov/Getty Images)

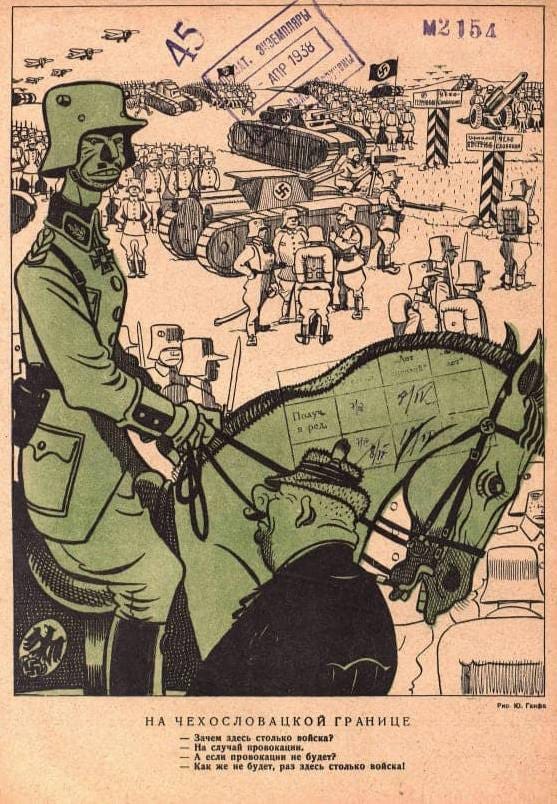

The Russian dissident and former World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov recognized the ploy immediately and tweeted an old Soviet joke regarding Nazi forces massing on the Czechoslovakian border in 1938:

“Why are there so many troops?”

“In case of a provocation.”

“What if there’s no provocation?”

“How could there not be with so many troops?!”

It would be as if Mexico amassed troops along the U.S. southern border, then “recognized the independence” of the Tucson People’s Republic and the El Paso People’s Republic, followed by an invasion to protect those separatist’s territorial sovereignty against the encroaching states of Arizona and Texas engulfing them. It’s a cockamamie ruse only an Alex Jones-level conspiracist would believe, and everyone in the West knows it. And Putin knows that we know it. And we know that Putin knows that we know it. So what is going on here? Why did the Russian autocrat feel the need to concoct such a pretense to war?

The proximate answer involves geopolitics, the relationship of NATO and the West with Russia, the consequences of the fall of the Soviet Union, economic leverage, greed, and whatever else drives dictators to want to color in more of the map in their country’s hue. Putin and his oligarch billionaire buddies, in conjunction with the state coffers they control, could easily just buy whatever it is they want from Ukraine using the same method most other countries use—trade. But apparently Putin would rather be the seller than the buyer, and the revanchism that has driven autocrats from time immemorial has parasitized Putin’s brain, driving him to abandon any such utilitarian calculations.

The ultimate answer for Putin’s pretense is that ever since war was outlawed in 1928 despots have felt the need to justify their pugnaciousness. In their 2017 book of how this happened and why, The Internationalists: How a Radical Plan to Outlaw War Remade the World, Yale University legal scholars Oona Hathaway and Scott Shapiro begin with the contorted legal machinations of lawyers, legislators, and politicians in the 17th century that made war, in the words of the Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz, “the continuation of politics by other means.” Those means included a license to kill other people, take their stuff, and occupy their land. Legally. How did this happen?

In 1625 the renowned Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius penned a 500-page legal justification for his country’s capture of the Portuguese merchant ship Santa Catarina when those two countries were at war. The document was titled The Law of War and Peace, and it argued, in short, that if individuals have rights that can be defended through courts, then nations have rights that can be defended through war. Why? Because there was no world court to adjudicate disputes between nations. As a consequence, for four centuries nations have felt at liberty to justify their bellicosity through “war manifestos”—legal statements outlining their “just causes” for “just wars.” Hathaway and Shapiro compiled over 400 such documents into a database on which they conducted a content analysis—that is, a catalogue of reasons why nations said they had to fight. The most common rationalizations for war were self-defense (69 percent); enforcing treaty obligations (47 percent); compensation for tortious injuries (42 percent); violations of the laws of war or law of nations (35 percent); stopping those who would disrupt the balance of power (33 percent); and protection of trade interests (19 percent).

These war manifestos are, in short, an exercise in motivated reasoning employing the confirmation bias, the hindsight bias, the myside bias, and other cognitive heuristics to justify a predetermined end. Instead of “I came, I saw, I conquered,” these declarations read more like “I was just standing there minding my own business when the other guy threatened me. I had to defend myself by attacking him preemptively. It’s all his fault.” The problem with this arrangement is obvious. Call it the moralization bias: the belief that our cause is moral and just and anyone who disagrees is not just wrong but immoral.

In 1917, with the carnage of the First World War evident to even war enthusiasts, a Chicago corporate lawyer named Salmon Levinson reasoned, “We should have, not as now, laws of war, but laws against war; just as there are no laws of murder or of poisoning, but laws against them.” With the support of the American philosopher John Dewey, the French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand, the German Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann, and the U.S. Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg, Levinson’s dream of war outlawry came to fruition with the “General Pact for the Renunciation of War,” also known as the Peace Pact, or the Kellogg-Briand Pact, signed in Paris in 1928. War was outlawed.

Given the number of wars since 1928—not the least of which was the Second World War that exceeded the hemoclysm of its predecessor by an order of magnitude—what happened? The moralization bias was in full flowering, of course, but there was also a lack of enforcement. That began to change after the ruinous World War II, when the concept of “outcasting” took hold, the most common example being economic sanctions. “Instead of doing something to the rule breakers,” Hathaway and Shapiro explain, noting that this usually involved attacking the offending nation, “outcasters refuse to do something with the rule breakers.” This principle of exclusion doesn’t always work (Cuba and North Korea come to mind), but sometimes it does (Turkey and Iran perhaps), and it is almost always better than war. The result, the researchers show, is that “interstate war has declined precipitously and conquests have almost completely disappeared.” Almost.

That the outlawing of war has not eliminated war is no more reason to give up on outlawry than that we should eliminate laws against murder just because murder rates have not bottomed out at zero. Homicide rates have, in fact, dropped precipitously over the centuries, as have the frequency and destructiveness of international wars, interstate conflicts, and civil wars, so the system works, even if imperfectly. Why it works requires an understanding of what leads countries to become more or less belligerent.

In their book Triangulating Peace: Democracy, Interdependence, and International Organizations, the political scientists Bruce Russett and John Oneal use a multiple logistic regression model on data from the Correlates of War Project that recorded 2,300 militarized interstate disputes between 1816 and 2001. Assigning each country a democracy score between 1 and 10 (based on the Polity Project that measures how competitive its political process is, how openly its leaders are chosen, how many constraints on a leader’s power are in place, the transparency of the democratic process is, the fairness of its elections, etc.), Russett and Oneal found that when two countries are fully democratic (that is, they score high on the Polity scale) disputes between them decrease by 50 percent; but when one member of a county pair was either a low-scoring democracy or a full autocracy, it doubled the chance of a quarrel between them.

When you add a market economy and international trade into the triangular equation it decreases the likelihood of conflict between nations. Russett and Oneal found that for every pair of at-risk nations, when they entered the amount of trade (as a proportion of GDP) they found that countries that depended more on trade in a given year were less likely to have a militarized dispute in the subsequent year, controlling for democracy, power ratio, great power status, and economic growth. In general, the data show that liberal democracies with market economies are more prosperous, more peaceful, and fairer than any other form of governance and economic system. In particular, they found that democratic peace happens only when both members of a pair are democratic, but that trade works when either member of the pair has a market economy. In other words, trade was even more important than democracy (although the latter is important for other reasons as well.)

Finally, the third vertex of Russett and Oneal’s triangle of peace is membership in the international community, a proxy for transparency. Evil is more likely to thrive in secret. Openness and transparency make it harder for dictators and demagogues to commit violence and genocide. To test this hypothesis, Russett and Oneal counted the number of International Governmental Organizations (IGOs) that every pair of nations jointly belonged to and ran a regression analysis with democracy and trade scores, finding that, overall, democracy, trade, and membership in IGOs all favor peace, and that a pair of countries that are in the top tenth of the scale on all three variables are 83 percent less likely than an average pair of countries to have a militarized dispute in a given year.

Using data from the Correlates of War project to test their theory that the outlawry of war and the outcasting of bad actors works to reduce their nefarious influence, Hathaway and Shapiro found that between 1816 and 1928 there was, on average, approximately one conquest every ten months, or 1.21 conquests per year. Another way to conceptualize this is that during this period a nation had a 1.33 percent chance of being conquered, which translates into states losing territory once in an ordinary human lifetime. And the average amount of real estate lost was substantial: 295,486 square kilometers (183,606 square miles) per year, or about 11 Crimeas per year for over a century. That’s a lot of land! (By comparison, California is 163,696 square miles, Texas is 268,597 square miles.)

The span from 1929-1948 wasn’t much better at 1.15 per year, one every ten months, and an average loss of 240,739 square kilometers (149,588 square miles). But everything changed after the Second World War when outcasting took effect—primarily through economic sanctions—and the average number of conquests per year fell to .26 per year, or one every 3.9 years, with an average loss of only 14,950 square kilometers per year. From this data Hathaway and Shapiro conclude:

The likelihood that any individual state would suffer a conquest in an average year plummeted from 1.33 percent a year to .17 percent from 1949 on. After 1948, the chance an average state would suffer a conquest fell from once in a lifetime to once or twice a millennium.

Thus, it is rational to conclude that with broad support from the UN, the EU, and U.S. allies, President Biden’s sanctions against Russia in proportion to its military incursions into Eastern Ukraine is the right response. These include: shutting down the Russia-to-Germany Nord Stream 2 pipeline to hurt the multibillion-dollar project of Russia’s Gazprom energy company, freezing bank assets under U.S. jurisdiction of Russian oligarchs who have over $80 billion in investments, sanctions imposed on individuals listed on a Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) and Blocked Persons List through the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, limit trade through sectoral sanctions applied to specific Russian firms in energy, finance, technology and defense sectors as part of a Sectoral Sanctions Identifications List, and taking Russia out of the SWIFT financial system, which moves money from bank to bank around the globe, which will immediately damage Russia’s economy.

Predictably, Republicans called Biden’s sanctions too little too late, but what is the alternative? U.S. troops on the ground in Ukraine for years or decades? Armed conflict that could escalate into a nuclear exchange, something Putin has publicly stated is not off the table? Equally predictably, the former president of Trump Steaks, Trump Airlines, Trump University, and the United States declared Putin’s move “genius” on a right-wing talk radio show, adding “So Putin is now saying it’s independent—a large section of Ukraine. I said, how smart is that? And he’s gonna go in and be a peacekeeper. We could use that on our southern border. That’s the strongest peace force I’ve ever seen. There were more army tanks than I’ve ever seen. They’re gonna keep peace, all right."

No matter how unsatisfying a response such sanctions may seem against a bully like Putin, we have merely to recall the devastation of the Second World War, or the massive costs of the U.S.’s two-decade involvement in two Middle Eastern wars, and compute the cost-benefit ratio. Outcasting is better than armed conflict.

Putin’s problem is that he’s a tyrant out of time, a 19th-century potentate in a 21st-century world that—hopefully—will not tolerate his revanchist aspirations. Let us heed the words of the historian John Emerich Edward Dalberg Acton, better known as Lord Acton, who penned this observation in an 1887 letter: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men.” Putin is a bad man whose absolute power over Russia has corrupted him absolutely. We must not let it corrupt us.

This is a very interesting article. I am not sure how much of the 'peace' of the second half of the 20th century is due to democracy, trade, etc. I think that the Pax Americana played a major role in this, too. The US military has been intervening as the World's Police across the globe for decades and that has certainly been a deterrent to petty dictators.

In any case, the conclusion is solid: exile from the community of modern economies is a better, cheaper solution than sending young men (& now women) to war. Sure, some complain that sanctions are not always effective but, as Afghanistan showed the world - twice - neither is conquest.

Sanctions are useless. The people will pay for it, the politicians won't. Higher energy prices drive up a lot of other prices and the poorest people in the world will suffer even more. Ukraine is the fault of the West: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JrMiSQAGOS4&t=5s