The Bomb, the Man, the Morality

Christopher Nolan's magisterial film "Oppenheimer" renews debate on the use of nuclear weapons to end World War II, as a deterrent to future use, and the nature of moral conflicts

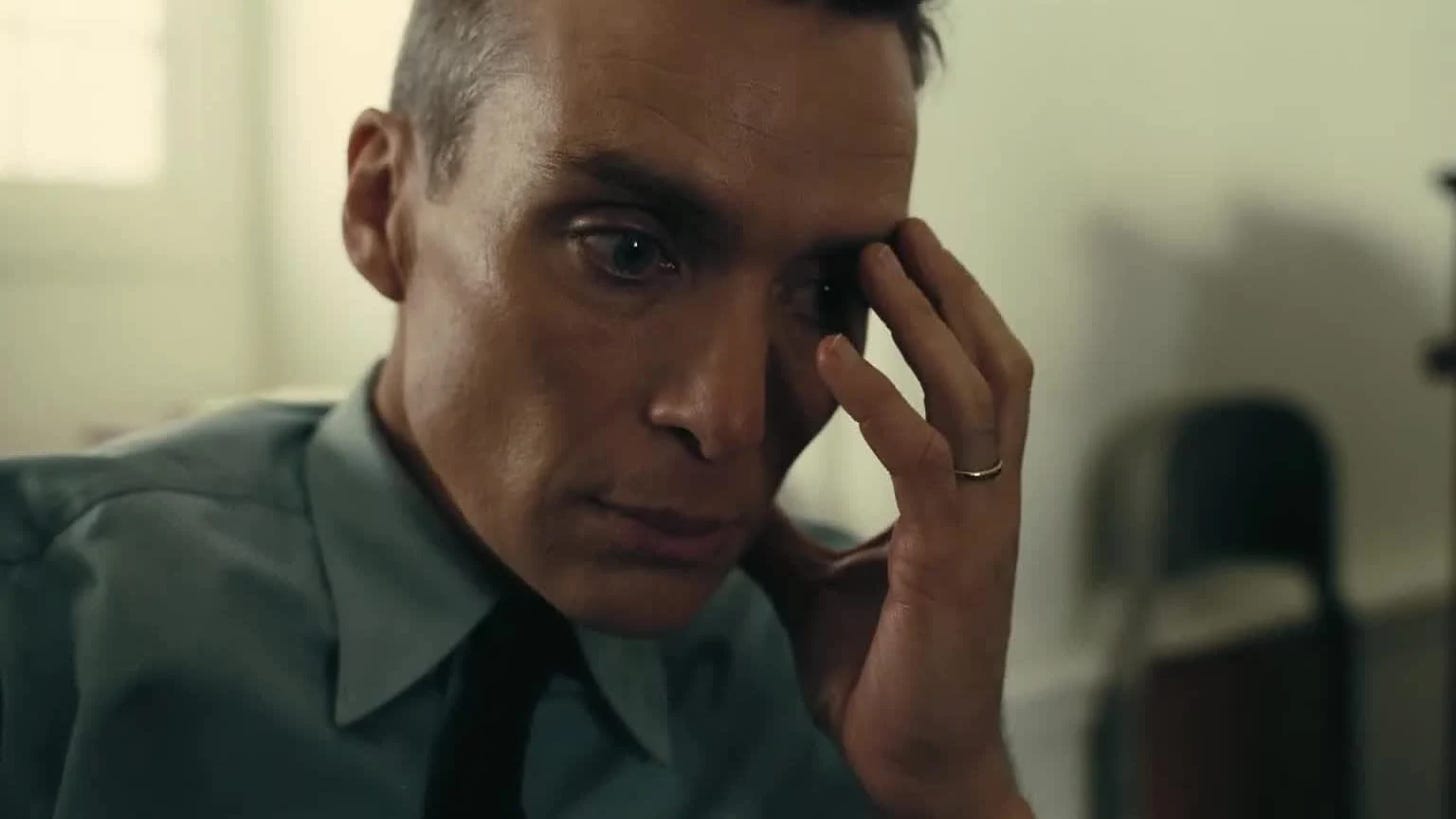

There is a poignant scene in Christopher Nolan’s tour de force biopic of the man the film director considers to be “the most important person who ever lived,” J. Robert Oppenheimer (cloned by Cillian Murphy), when the “father of the atomic bomb” is facing a government tribunal in a 1954 security clearance hearing in what can only be described as a Soviet-style show trial, which is ironic since this was in the midst of anti-Communist McCarthyism in which the verdict is determined before the case is on the docket. Suddenly the scene shifts from bureaucratese banter over mundane comings and goings of Oppenheimer before and during the war (he had professorial appointments at the University of Göttingen in Germany, Caltech in Pasadena, UC Berkeley, and traveled considerably), to him sitting naked in his interrogation chair with his former lover (also nude), the psychiatrist and Communist Jean Tatlock (a sultry Florence Pugh) rhythmically riding him while staring down his wife Kitty sitting behind her husband in support, appearing at once angry and hurt (she knew about the sporadic but long-lasting affair).

I don’t know if Nolan intended the scene to portray the parallel personal and public moral conflicts Oppenheimer experienced (probably, since Nolan has emerged as the most brilliant and creative filmmaker of our time), but among the many insights that this epic film conveys it is that the human condition is rarely black-and-white. Approach-avoidance conflicts permeate life, culture, and politics.

Oppenheimer loved his wife and the two children she bore him (one at Los Alamos during the construction of the bomb)…and he still harbored feelings for his former lover, whom he met in 1936 when he was a professor of physics at UC Berkeley and she was a medical student at Stanford University (it was not just sex—Oppenheimer proposed to her, twice, and she turned him down, believing that she was possibly a lesbian, among other reasons).

Oppenheimer married Katherine “Kitty” Puening (a German-born American botanist played with appropriate emotional gravitas by Emily Blunt) in 1940, and after moving to Los Alamos to work on the bomb project he saw Tatlock one final time in 1943, traveling from the lab to her apartment in San Francisco after she wrote to him about her emotional troubles, the intimate details of which we know about because US Army agents had been surveilling her. The report of the lovers night together made its way up the chain of command to Oppenheimer’s boss, Army Major General Leslie R. Groves (perfectly portrayed by Matt Damon).

Long suffering from clinical depression, Tatlock took her own life in 1944 (also reinacted in the film with her kneeling naked on a pile of cushions in the bathroom, head submerged in a partly-filled bathtub, a scene so odd that some have speculated she was murdered), followed by Oppenheimer’s grief over the loss as his long-suffering wife struggles to find any support to offer while also feeling crushed by the betrayal of her love.

The security hearings were another source of moral conflict for Oppenheimer, and the film toggles back and forth between them and the physicist’s life and work (the splintered linear timeline in the film is so artfully presented that viewers have no problem following the plot even as scenes leap across years of time). At war’s end Oppenheimer, along with everyone else who toiled at Los Alamos to build the bomb, was ecstatic at its success in bringing about the surrender of Japan (more on this below), and in appreciation Groves awarded the physicist a Certificate of Appreciation. Already Oppenheimer’s moral ambivalence showed in his acceptance speech when he noted:

If atomic weapons are added as new weapons of war to the arsenals of a warring world, the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and Hiroshima.

After the war Oppenheimer took up residence as the Director of the Institute for Advanced Studies at Princeton, where he grew concerned about the nuclear arms race between the US and USSR. But Oppenheimer’s youthful flirtations with Communism in the 1930s—fueled as it was by exposure to the underbelly of American capitalism that left so many people impoverished—came back to haunt him during the 1950’s Red Scare McCarthyism when FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover opened a file on him, wire-tapped his phone, and surveilled his every move. By then Oppenheimer was a staunch critic of Stalin and the Soviet Union and a thorough-going defender of the American way of life, but in a witch hunt the facts don’t matter when the verdict is determined ahead of time. (“Give me the man and I will find the crime” boasted Stalin’s secret police chief Lavrentiy Beria.) The fix was in to strip Oppenheimer of his Q security clearance (atomic secrets) and that is what the security hearings set out to do.

Oppenheimer’s Beria was Lewis Straus (an almost unrecognizable Robert Downey Jr.), one of the original commissioners of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), a staunch supporter of the development of Edward Teller’s “Super” H-bomb, and believer in the game-theoretic model that deterrence is best found in a massive nuclear arsenal. As one of the most famous people in the world (Time magazine featured him on its cover twice) Oppenheimer’s opinions about nuclear weapons and war thus posed a threat to those in the Eisenhower administration who could brook no dissent from nuclear orthodoxy (that climaxed in what Eisenhower himself identified in his farewell address as a “military-industrial complex”). Straus informed Oppenheimer that he had damning evidence against him but would drop the charges if Oppenheimer would simply quit his consultant position with the AEC and forego his Q security clearance. A man of clear conscious and firm conviction, Oppenheimer refused, telling Straus that this would “mean that I accept and concur in the view that I am not fit to serve this government, now that I have now served for some twelve years. This I cannot do.”

As Oppenheimer prepared his case he was advised by no less a personage than Albert Einstein, who knew a few things about government investigations into peoples’ private lives, advising his friend not to sanction his own victimhood by participating in a show trial. “The German calamity of years ago repeats itself,” Einstein cautioned. “People acquiesce without resistance and align themselves with the forces of evil.” When it was clear Oppenheimer was going to defend his sacred honor, Einstein told the press: “I admire him not only as a scientist but also a great human being.” Despite supportive testimony from such colleagues as Hans Bethe, George Kennan, Johnny von Neumann, and James Conant, and even General Groves himself, after a grueling 27 hours on the stand the tribunal voted 2-1 to strip the scientist of his Q security clearance, with Ward Evans as the dissenting voice pronouncing “I personally think that our failure to clear Dr. Oppenheimer will be a black mark on the escutcheon of our country.” Indeed it was, and in December, 2022, 70 years after the fact and 55 years after Oppenheimer died of throat cancer in 1967, Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm revoked the revocation and Oppenheimer’s security clearance was restored, along with his honor.

But Oppenheimer’s deepest moral conflict was over the bomb itself. Of course, operating under the best intelligence that indicated the Nazis were working on their own bomb project, it was altogether rational for the U.S. to undertake its own bomb project, initially instigated by Albert Einstein (aided by Leo Szilard) in the now-famous 1939 letter to President Roosevelt that “a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium” could lead “to the construction of bombs, and it is conceivable—though much less certain—that extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed. A single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory.”

Through numerous twists and turns it came down to Groves finding the right scientist to orchestrate a pantheon of independent thinkers to focus on the task of building the bomb before the enemy does. But what if this ultimate weapon also ushers in a new world in which its development—Nazis notwithstanding and ultimately defeated—results in an arms race in which each side believes that the most rational strategy is to arm to the teeth…just in case the other side does? This is called the Hobbesian Trap (after Thomas Hobbes who first articulated the problem), or the security dilemma (after game theory analysis) or the other-guy problem—”I don’t want nukes but the other guy does, so….” Thus the approach-avoidance conflict that confronted Oppenheimer during and after Los Alamos. “We may be likened to two scorpions in a bottle, each capable of killing the other, but only at the risk of his own life,” he analogized.

The narrative tension of the film reaches a climax on July 16, 1945, when the Trinity plutonium bomb was detonated in White Sands, New Mexico, with the energy equivalent of 22 kilotons (22,000 metric tons) of TNT, sending a mushroom cloud 39,000 feet into the atmosphere. The explosion left a crater 76 meters wide filled with radioactive glass called trinitite (melted quartz grained sand). It could be heard as far away as El Paso, Texas.

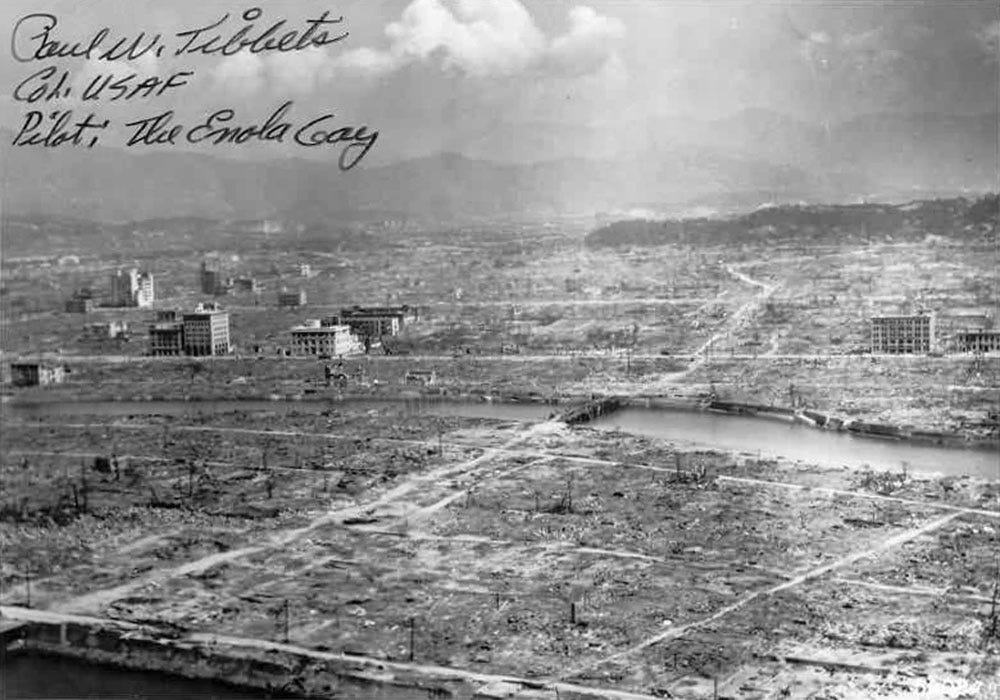

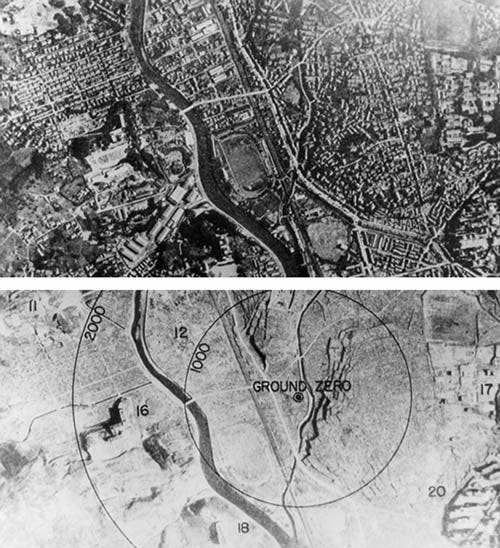

On August 6, 1945, the Little Boy gun-type uranium-235 bomb exploded with an energy equivalent of 16–18 kilotons of TNT, flattening 69 percent of Hiroshima’s buildings and killing an estimated 80,000 people and injuring another 70,000. Three days later the Fat Man plutonium implosion-type bomb with the energy equivalence of 19-23 kilotons of TNT leveled around 44 percent of Nagasaki, killing an estimated 35,000 to 40,000 people and severely wounding another 60,000.1

Aftermath of Hiroshima

Before and aftermath of Nagasaki

As documented in the memo below dated August 10, 1945, if the Japanese had not surrendered Major General Groves had another Fat Man-type plutonium implosion bomb ready to go after August 24 that would have likely killed another 50,000 to 100,000 people.2

Had the Japanese military hardliners had their way to continue the war into the fall, Groves had three more bombs readied for September and another three for October. Here he instructs his Chief of Staff that the next bomb will be ready to drop on after August 24. Emperor Hirohito capitulated on August 15, thereby saving millions of lives of his citizens. President Harry Truman was not exaggerating when he threatened Japan with “a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this Earth.”

Like Oppenheimer, Truman agonized about dropping more nukes on Japan, troubled as he was by the thought of more innocents and noncombatants being killed. He wrestled that decision away from the military. (Note Groves’ handwritten addendum to his memo above that “It is not to be released on Japan without express authority from the President.” U.S. presidents have had sole authority to use nuclear weapons ever since.)

However, further bombings proved unnecessary. On August 15 Emperor Hirohito, against the wishes of some of Japan’s military leaders, announced on the radio that Japan would capitulate. On September 2 they signed the surrender documents in Tokyo Bay, ending the Second World War.3

Was the Atomic Bomb project necessary? Since 1945 a cadre of critics have proffered the claim that atomic bombs were unnecessary to bring about the end of World War II (or, at least, the Fat Man Nagasaki bomb was superfluous), and thus this act was immoral, illegal, or even a crime against humanity. Robert Oppenheimer and other physicists like Leo Szilard who worked on the Manhattan Project expressed reservations. “The physicists have known sin,” Oppenheimer opined. He went to Truman (also depicted in the film) and confessed “Mr. President. I feel I have blood on my hands,” to which the President recalled “I told him the blood was on my hands — to let me worry about that.” Truman promptly dismissed Oppenheimer and told Secretary of State Dean Acheson, “I don’t want to see that son-of-a-bitch in this office ever again.”4

In 1946 the Federal Council of Churches issued a statement declaring, “As American Christians, we are deeply penitent for the irresponsible use already made of the atomic bomb. We are agreed that, whatever be one’s judgment of the war in principle, the surprise bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are morally indefensible.”5 In 1967 the linguist and contrarian politico Noam Chomsky called the two bombings “the most unspeakable crimes in history.”6

More recently, in his history of genocide titled Worse Than War, the historian Daniel Goldhagen opens his analysis by calling the U.S. President Harry Truman “a mass murderer” because in ordering the use of atomic weapons he “chose to snuff out the lives of approximately 300,000 men, women and children.” Goldhagen opines that “it is hard to understand how any right-thinking person could fail to call slaughtering unthreatening Japanese mass murder.”7 Goldhagen defines “genocide” broadly enough to equate it with “mass murder” (without ever defining what, exactly, that means). In morally equating Harry Truman with Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Pol Pot, Goldhagen allows himself to be constrained by the categorical thinking that prevents one from discerning the different kinds, levels, and motives for large scale military violence. By this reasoning, nearly every act that kills a large number of people could be considered genocidal because there are only two categories — mass murder and non-mass murder.

By contrast, continuous thinking allows us to distinguish the differences between types of mass killings (some scholars define genocide as one-sided killing by armed people of unarmed people), their context (during a state war, civil war, ethnic cleansing), motivations (termination of hostilities or extermination of a people), and quantities (hundreds to millions) along a sliding scale. In 1946 the Polish jurist Raphael Lemkin created the term genocide and defined it as “a conspiracy to exterminate national, religious or racial groups.”8 That same year the U.N. General Assembly defined genocide as “a denial of the right of existence of entire human groups.”9 More recently, in 1994 the highly respected philosopher Steven Katz defined genocide as “the actualization of the intent, however successfully carried out, to murder in its totality any national, ethnic, racial, religious, political, social, gender or economic group.”10

By these definitions, the dropping of Fat Man and Little Boy were not acts of genocide. The difference between Truman and the others is in the context and motivation of the act. In their genocidal actions against targeted people, Hitler, Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot had as their objective the total elimination of a group. The killing would only stop when every last pursued person was exterminated (or if the perpetrators were stopped or defeated). Truman’s goal in dropping the bombs was to end the war with Japan (which it did), not to eliminate the Japanese people (which it didn’t). That the U.S. provided considerable financial, personnel, and material support to help rebuild Japan into a world economic power puts the lie to the eliminationist accusation.11

More broadly morally, if we ground morality in the survival and flourishing of sentient beings,12 by that measure, then not only did Fat Man and Little Boy end the war and stop the killing, they saved lives — very probably millions of lives, both Japanese and American. My father, Richard Shermer, was possibly one such survivor. During the Second World War he served aboard the USS Wren (DD-568), a Fletcher-class destroyer assigned to protect aircraft carriers and other large capital ships from Japanese submarines and from Kamikaze planes on what was called antiaircraft radar picket watch. His ship was so attacked several times but sustained no major damage. The Wren was part of the larger fleet that was working its way toward Japan, escorting the carriers whose planes were bombarding the Japanese homeland in preparation for the planned invasion. My father told me that everyone onboard dreaded that day because they had heard of the horrific carnage resulting from the invasion of just two tiny islands held by the Japanese — Iwo Jima and Okinawa. If that was any indication of what was to come with a full-scale invasion, the contemplation of it was almost too much to bear.13

The author’s father, Richard Shermer, in 1945, serving aboard the USS Wren.

During the invasion of Iwo Jima there were approximately 26,000 American casualties that included 6,821 dead in the 36-day battle. How fiercely did the Japanese defend that little volcanic rock 700 miles from Japan? Of the 22,060 Japanese soldiers assigned to fight to the bitter end, only 216 survived.14 The subsequent battle for Okinawa, only 340 miles from the Japanese mainland, was fought even more ferociously, resulting in a staggering body count of 240,931 dead, including 77,166 Japanese soldiers, 14,009 American soldiers, plus an additional 149,193 Japanese civilians living on the island who either died fighting or committed suicide rather than let themselves be captured.15 With an estimated 2.3 million Japanese soldiers and 28 million Japanese civilian militia prepared to defend their island nation to the death,16 it was clear to all what an invasion of the Japanese mainland would entail.

It is from these cold hard facts that Truman’s advisors estimated that between 250,000 and one million American lives would be lost in an invasion of Japan.17 General Douglas MacArthur estimated that there could be a 22:1 ratio of Japanese to American deaths, which translates to a minimum death toll of 5.5 million Japanese.18 By comparison, cold though it may sound, the body count from both atomic bombs — about 200,000–300,000 total (Hiroshima: 90,000–166,000 deaths, Nagasaki: 60,000–80,000 deaths19) — was a bargain.

In any case, if Truman hadn’t ordered the bombs dropped, General Curtis LeMay and his fleet of B-29 bombers would have continued pummeling Tokyo and other Japanese cities into rubble. When asked to predict when the war would end based on his bombing program, LeMay said September 1, because that was when there would be nothing left of Japan to bomb. The death toll from conventional bombing would have been just as high as that produced by the two atomic bombs, if not higher. Previous mass bombing raids had produced Hiroshima-level death rates, and it is likely that more than just two cities would have been destroyed before the Japanese surrendered. Compare, for example, Little Boy’s energy equivalent of 16,000–19,000 tons of TNT to the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey estimate that this was the equivalent of 220 B-29s carrying 1,200 tons of incendiary bombs, 400 tons of high-explosive bombs, and 500 tons of anti-personnel fragmentation bombs, with an equivalent number of casualties.20 In fact, on the night of March 9–10, 1945, 279 B-29s dropped 1,665 tons of bombs on Tokyo, leveling 15.8 square miles of the city, killing 88,000 people, injuring another 41,000, and leaving another million homeless.21

On the night of March 9–10, 1945, 279 B-29s dropped 1,665 tons of bombs on Tokyo, leveling 15.8 square miles of the city, killing 88,000 people, injuring another 41,000, and leaving another million homeless. This is the result.

These facts also help refute the claim that the alternative scenario of dropping an atomic bomb on an uninhabited island or bay to demonstrate its destructive force would have worked to convince the Japanese to surrender. Given that they refused to capitulate even after numerous cities were obliterated by conventional bombs and Hiroshima was erased from the map by an atomic bomb it seems unlikely this more benign strategy would have worked.22

On balance, then, dropping the atomic bombs was the least destructive of the options on the table. Although we wouldn’t want to call it a moral act, it was in the context of the time the least immoral act by the criteria of lives saved. That said, we should also recognize that the several hundred thousand killed is still a colossal loss of life. The fact that the invisible killer of radiation continued its effects long after the bombings should dissuade us from ever using such weapons again. Along that sliding scale of evil, in the context of one of the worst wars in human history that included the singularly destructive Holocaust of six million murdered, it was not, pace Chomsky, the most unspeakable crime in history — not even close — but it was an event in the annals of humanity never to be forgotten and, hopefully, never to be repeated.

References

Rhodes, Richard. 1986. The Making of the Atomic 1 Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster.

The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II, A Collection of Primary Sources. National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 162. George Washington University. https://bit.ly/2WMuDNM See also: “The Third Shot.” https://bit.ly/39eCTuW

DeNooyer, Rushmore. 2015. The Bomb. PBS documentary. https://to.pbs.org/3f2yyfw

Bird, Kai and Martin J. Sherwin. 2007. American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Knopf, 332.

Quoted in: Marty, Martin E. 1996. Modern American Religion, Vol 3: Under God, Indivisible, 1941–1960. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 117.

Chomsky Noam. 1967. “The Responsibility of Intellectuals.” The New York Review of Books, 8(3).

Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah. 2009. Worse Than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity. New York: PublicAffairs, 1, 6.

Lemkin, Raphael. 1946. “Genocide.” American Scholar, 15(2), 227–230.

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 96(1): “The Crime of Genocide.”

Katz, Steven T. 1994. The Holocaust in Historical Perspective, Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kugler, Tadeusz, Kyung Kook Kang, Jacek Kugler, Marina Arbetman-Rabinowitz, and John Thomas. 2013. “Demographic and Economic Consequences of Conflict.” International Studies Quarterly, March, 57(1), 1–12.

Shermer, Michael. 2015. The Moral Arc: How Science and Reason Lead Humanity to Truth, Justice, and Freedom. New York: Henry Holt, 11.

In 2002 I attended the reunion of the Wren crew in my father’s stead and confirmed his memories.

Toland, John. 1970. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945. New York: Random House, 731.

“The Cornerstone of Peace — Number of Names Inscribed.” Kyushu-Okinawa Summit 2000: Okinawa G8 Summit Host Preparation Council, 2000. See also: Pike, John. 2010. “Battle of Okinawa.” Globalsecurity.org; Manchester, William. 1987. “The Bloodiest Battle of All.” The New York Times, June 14.

Giangreco, Dennis M. 2009. Hell to Pay: Operation Downfall and the Invasion of Japan 1945–1947. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 121–124.

Giangreco, Dennis M. 1998. “Transcript of ‘Operation Downfall [U.S. Invasion of Japan]: US Plans and Japanese Counter-Measures. Beyond Bushido: Recent Work in Japanese Military History. https://bit.ly/2ZYCLwu See also: Maddox, Robert James. 1995. “The Biggest Decision: Why We Had to Drop the Atomic Bomb.” American Heritage, 46(3).

Skates, John Ray. 2000. The Invasion of Japan: Alternative to the Bomb. University of South Carolina Press, 79.

Putnam, Frank W. 1998. “The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission in Retrospect.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, May 12, 95(10), 5426–5431.

K’Olier, Franklin (Ed.) 1946. United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Sum 20 mary Report (Pacific War). Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office. https://bit.ly/32TsOSL

Rhodes, 1984, op cit., 599.

Ibid.

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, Executive Director of the Skeptics Society, and the host of The Michael Shermer Show. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His new book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational.

Back in college a prof overheard some of us debating the morality of atomic bombs and he interjected - The real debate should be over the morality of killing civilians, and not over what particular weapon is employed.

The atomic bomb is one of those moral issues that really does feel like a "both sides" issue, because nuclear weapons are truly horrifying. But if the Japanese fascists had just surrendered, none of this would have happened. Those samurai lunatics were bloodthirsty animals who brutally butchered millions.