The Fear of Non-Existence

A reader asks "Is it normal to be afraid to die?" My answer follows

In response to this column and my other venues of communication I receive a steady stream of correspondence from many thoughtful people. Here is a recent one, reprinted with permission of the author:

Hello, my name is Nicholas and I just watched your video on Death or non-existence and now as a 72 year old man who has lost several love ones, I am concerned about my own Death and the possibility of non-existence. Though I am a Christian and believe in Jesus and the hope of an Afterlife, there is this nagging fear I have of when I die of never existing anymore and that terrifies me!

How does one face the fact one day they will die, there are no exceptions, no free passes, Death comes to all! Is it normal to be afraid to die???

Thank you,

Nicholas Krisfalusy

The Empyrean of God. Dante Alighieri’s 1320 poem The Divine Comedy is an imaginative vision of the afterlife inspired by medieval Christian theologians. The artist Gustave Doré illustrated God’s empyrean for an 1892 edition of the work.

The referenced video is probably this one with Ben Shapiro on his Sunday Special show…

…which I did during the media tour for my 2018 book Heavens on Earth, about “The Scientific Search for the Afterlife, Immortality, and Utopia,” which informs my answer to Mr. Krisfalusy below (images from the book).

Dear Mr. Krisfalusy,

The fear you express in your letter is perfectly normal, even among religious believers, and confirms my lifelong suspicion (including when I was a born-again evangelical Christian from 1971-1978) that even though the vast majority of people believe in an afterlife and a soul that continues after the death of the body, doubts persist. How could they not? Out of the 100 billion people who lived and died before us, not one has come back from the dead or returned from heaven, at least to the satisfaction of most scientists and philosophers (and even theologians of differing faiths). And even though it is common at faith-based funerals to hear references to “seeing loved ones again,” or them “looking down upon us” (although hopefully not in bedrooms with future spouses), or their enjoyment of the fruits of heaven, or whatever, it is obvious that believers experience grief in measures not so different from that of nonbelievers when losing a close friend or family member.

The Ladder of Divine Ascent. Painted in the twelfth century, this image depicts the thirty rungs of the ladder representing the thirty stages of the ascetic life; the demons grappling the monks represent the many temptations of this life that might prevent one from reaching the next life. Jesus, upper right, welcomes monks who made it, while angels upper left and monks bottom right encourage seekers to press on. At the bottom left, Satan devours a fallen monk. From the collection of Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai.

The grieving response appears to be built into human nature, and Paleolithic sites of ritual burials strongly suggests that our distant ancestors may also have grieved for the dead, as in this site from Russia dated over 30,000 years old.

Burial of Man with Beads in Sunghir, Russia. Dated between 30,000 and 34,000 years old, this man was interred with 2,936 beads, along with 20 pendants and 25 rings, all made of mammoth ivory sewn into his clothing, since disintegrated, leaving this remarkable scene. Courtesy of José-Manuel Benito Álvarez.

What were these ancient peoples thinking when they buried their dead? Did they have some inchoate conception of an afterlife to which their charges would transcend from this life? We do not know, but at some point in those long-gone millennia the first beliefs in and conceptions about the afterlife arose. It is deeply ingrained in our cognition.

There is even evidence that many animal species grieve, most famously elephants (as in Jeffrey Masson’s moving book When Elephants Weep). In my book I describe an experiment by Karen McComb and her colleagues in which they placed objects about 25 meters from the elephants they were studying in Amboseli National Park in Kenya. In the first condition, they planted the skulls of a rhinoceros, buffalo, and elephant near 17 different elephant families, noting that their subjects spent the majority of their time carefully examining the skulls of their own species, smelling and touching them with their trunks. In a second condition a different set of 19 elephant families were confronted with a piece of wood, a piece of ivory, and an elephant skull. Predictably, their interests scaled from most to least relevant: ivory, skull, wood. But, McComb notes, “Their preference for ivory was very marked, with ivory not only receiving excessive attention in comparison with wood but also being selected significantly more than the elephant skull.”

When Elephants Grieve. The animal behaviorist Karen McComb photographed these elephants mourning the loss of family and group members. Photograph courtesy of Karen McComb.

These elephants also habitually touched and rolled the ivory with the sensitive soles of their feet, and picked it up in their trunks to hold and carry. Why? “Interest in ivory may be enhanced because of its connection with living elephants, individuals sometimes touching the ivory of others with their trunks during social behavior,” McComb hypothesizes. “Elephants may, through tactile or olfactory cues, recognize tusks from individuals that they have been familiar with in life.”

Imagine that: mourning the remains of someone you once knew. How human.

As for your own mortality, Nicholas, it is also perfectly natural to imagine yourself (or your soul) continuing on after the death of your body. Here is how I broached the subject in the opening lines of Heavens on Earth:

Imagine where you were before you were born. You can’t because you didn’t exist before you were born. The same problem arises in imagining your death. Try it. What comes to mind? Do you see your body as part of a scene, perchance presented in a casket surrounded by family and friends at your funeral? Or maybe you see yourself in a hospital bed after expiring from an illness, or on the floor of your home following a fatal heart attack? None of these scenarios—or any others your imagination might conjure—are possible, because in all cases in order to observe or imagine a scene you must be alive and conscious. If you are dead you are neither. You can no more visualize yourself after you die than you can picture yourself before you were born.

To experience something you must be alive, so we cannot personally experience death. Thus, to your question Nicholas, there’s nothing to fear about death because you can’t experience it, and if there is no afterlife you’ll never know it (and if there is, you’ll find out then and there). Yet, we know death is real because every one of the 100 billion people who lived before us is gone. This leads us to concoct various solutions to this paradox, including that death is not final and that “you”—whatever that may be, which has been imagined to be anything from a non-material soul to a resurrected physical figure (one Christian denomination even suggests you’ll be resurrected as a 30-year old body in heaven because that is the age Jesus was when crucified, plus we’re at our physical peak around that age…alas). Some psychologists have even postulated that awareness of our own mortality is so existentially devastating that it leads to “terror management” in the form of creative construction of everything from personal legacies to civilization. This idea even has a name: Terror Management Theory, inspired by Ernst Becker’s book The Denial of Death. In my book I explain why I’m skeptical of this theory, but the point here is that most people don’t just want to “live on through the hearts of their countrymen,” as Woody Allen griped, they want to live on in their apartments.

It is the continuation of self that most people have in mind for immortality and the afterlife. And here I am also skeptical of the science fiction scenario of uploading your mind and memories (your MEMself) to the cloud in some giant digital computer file, because that wouldn’t be you per se; it would just be a copy of you. If such a brain scan of your connectome (the cognitive equivalent of the genome) could be made while you are alive (through some super sophisticated MRI brain scanning machine), and said copy were uploaded to the cloud and turned on (none of this is even remotely possible), you’d be lying there in the scanner still experiencing the world through your point of view (your POVself) while your duplicate began a new existence that would veer from your life course. Religious afterlife scenarios face the same problem: if God copies your MEMself, then that’s just a duplicate of you in heaven while the real you remains in the grave. A deity would need to transport to heaven your POVself, with a continuity of existence from one moment to the next in tact (with, perhaps, a short sleep break in which you dream for awhile and then wake up in some other place).

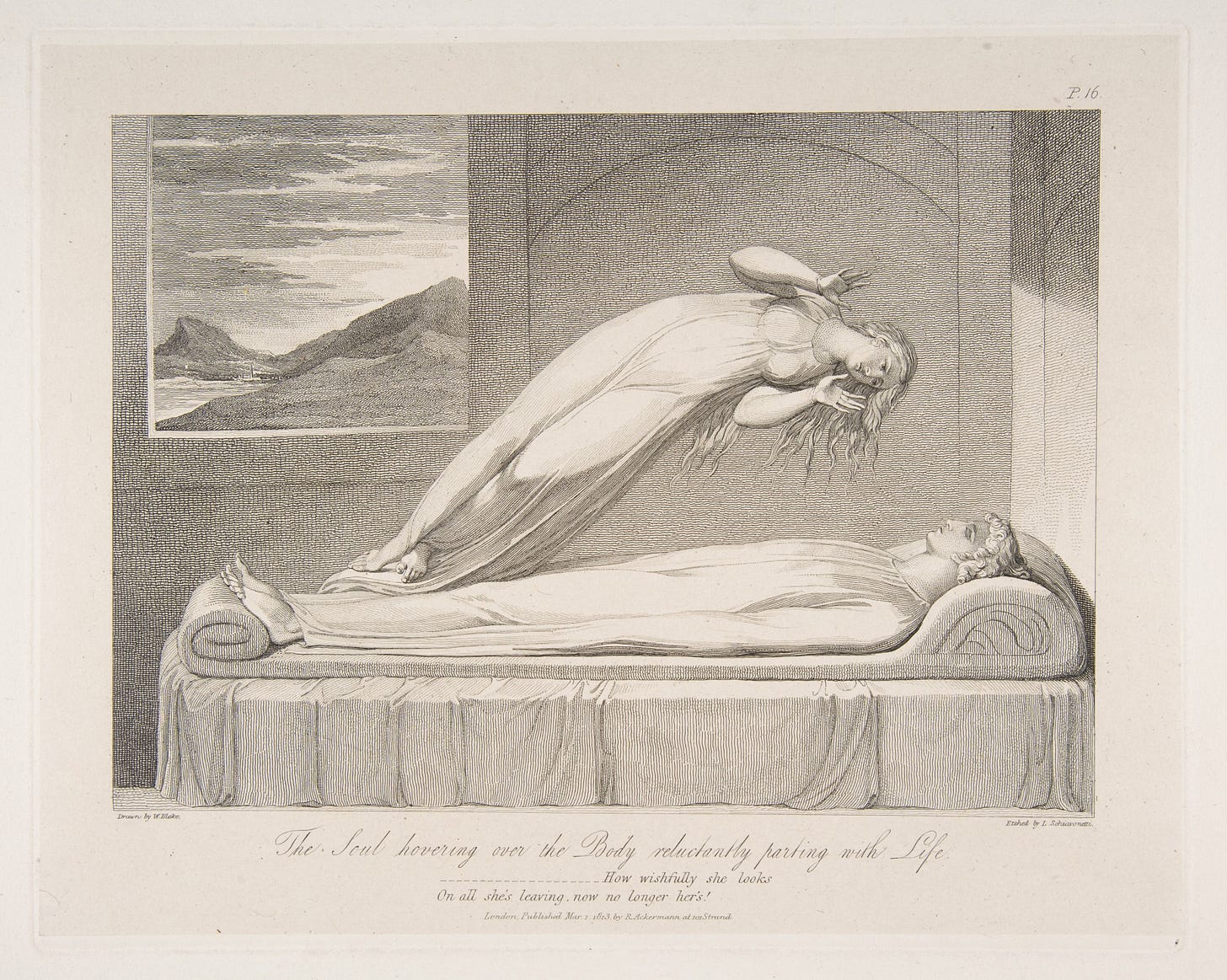

The Soul. William Blake’s portrayal of the soul departing the body upon death captures what most people believe to take place. An illustration from a series designed by Blake for an edition of the poem “The Grave” by Robert Blair, engraved by Louis Schiavonetti in 1813, titled The Soul Hovering over the Body, Reluctantly Parting with Life. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

When most people think of life after death they think of their POVself somehow continuing. They close their eyes for the last time on this dusty Earth, slip its surly bonds and ascend to some paradisiacal state where they will see their loved ones again and enjoy the fruits of their faith for eternity with their God and savior (assuming they chose the right one, which is almost entirely determined by what epoch and geographical location where one happened to have been born and raised). The only science-based proposal that stands any chance whatsoever of continuing the POVself (and even that is vanishingly slim) is cryonics, in which you have your brain and body frozen (don’t do the brain-only freeze because you will need your body for your complete self, as in the “embodied self”!) and reanimate at some future date when whatever it was that killed you can be cured. Of course, this still won’t leave you an eternal being because the Second Law of Thermodynamics will continue to chip away at your mortal body, leaving you forever chasing the elixir of immortality that science can never—not even in principle—conquer.

I might also comment briefly on the idea of living “forever” in “eternity.” Most people don’t give this much thought, content with the enchanted notion of continuing on in some state with those we love forever. That seems innocuous enough until you think about it for a moment. First, as Julia Sweeney notes in her Letting God of God monologue, when told by Mormon missionaries that if she accepts their faith she gets to spend eternity with her family, she replied, “Oh dear. That wouldn't be such a good incentive for me.” Julia’s monologues recount the many challenges she faced with her parents and siblings growing up, affirming the Anna Karenina principle, articulated by Leo Tolstoy: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” It’s hard to imagine families remaining happy…forever.

Second, my first college professor, Richard Hardison, had this question about heaven (when I “witnessed” to him about Jesus): “Are there tennis courts and golf courses?” In other words, are there any challenges? If there is no disease, sickness, aging, or death in heaven, if there are no obstacles to overcome and nothing to work for, what is there to do? Forever is a long time to be blissfully bored.

Third, if the Christian version of heaven is correct and you get to spend eternity with an omniscient and omnipotent deity who knows and controls everything you think, do and say, then as Christopher Hitchens famously opined, that would make heaven a “celestial North Korea” from which “you would never be able to escape,” a “place of endless praise and adoration, limitless abnegation and abjection of self.”

Like most people, I want to live a long and healthy life, and when the end comes I would prefer it be swift and painless rather than stretched out over months or years on life support systems that bankrupt families emotionally and financially. Nevertheless, I get the desire to continue indefinitely. If my four score and seven years were up and you asked if I’d like an extra year, assuming I had my bodily health and cognitive faculties about me, I would assent to the gift. How about an extra decade? Sure, I could go for that—write another book or two, time with my friends and family, maybe take up a new sport or hobby. How about a century? I wouldn’t turn it down, but it does bring up some awkward questions, like how many careers, marriages, hobbies, and homes would I have in that extra century? Offer me an extra millennium and now the visage begins to blur—I can’t see out that far. How about a thousand millennia? I have no idea what I would do for a million years! How about a thousand million years? That’s not even a quarter the age of the Earth, and less than one-thirteenth the age of the universe. And that’s still no where near eternity! You see where I’m going with this. The concept of an immortal being is literally inconceivable, and thus meaningless.

Nicholas, I don’t know what will happen to you after you die. No one does. Maybe there is an afterlife, maybe there isn’t. In a way, it doesn’t really matter because the only thing you can experience is the here and now. The past has already happened and the future has yet to unfold. That sounds anodyne, but in fact not to do so is a grave error in thinking I call Alvy’s Error (which I first defined in Scientific American), from Woody Allen’s character in his 1977 film Annie Hall, who in a flashback scene as a depressed young boy won’t do his homework because, he explains to the family doctor, “The universe is expanding. Well, the universe is everything and if it’s expanding some day it will break apart and that will be the end of everything.” His exasperated mother upbraids the youth, “What has the universe got to do with it?! You’re here in Brooklyn. Brooklyn is not expanding!”

Alvy’s Error is assessing the purpose of something at the wrong level of analysis. The level at which we should assess our actions is the human time scale of days, weeks, months, and years—our four-score ± 10 lifespan—not the billions of years of the cosmic calendar. The mistake is often made by theists when arguing that without a source external to our world to vouchsafe morality and meaning, nothing really matters. My type specimen of the error comes courtesy of William Lane Craig in his 2009 debate at Columbia University with the Yale philosopher Shelly Kagan. According to Craig:

On a naturalistic worldview everything is ultimately destined to destruction in the heat-death of the universe. As the universe expands it grows colder and colder as its energy is used up. Eventually all the stars will burn out, all matter will collapse into dead stars and black holes, there will be no life, no heat, no light, only the corpses of dead stars and galaxies expanding into endless darkness. In light of that end it’s hard for me to understand how our moral choices have any sort of significance. There’s no moral accountability. The universe is neither better nor worse for what we do. Our moral lives become vacuous because they don’t have that kind of cosmic significance.

Kagan properly nailed Craig, referencing the latter’s example of godless Nazi torturers: “This strikes me as an outrageous thing to suggest. It doesn’t really matter? Surely it matters to the torture victims whether they’re being tortured. It doesn’t require that this make some cosmic difference to the eternal significance of the universe for it to matter whether a human being is tortured. It matters to them, it matters to their family, and it matters to us.”

Craig committed a related mistake when he argued that, “Without God there are no objective moral values, moral duties, or moral accountability.” And: “If life ends at the grave then ultimately it makes no difference whether you live as a Stalin or a Mother Teresa.”

Call this Craig’s Categorical Error: assessing the value of something by the wrong category of criteria. We live in the hear-and-now, not the hearafter, so our actions must be judged according to the criteria of this category, whether or not the category of a God-granted hereafter exists. Whether you behave like a Russian dictator who murdered tens of millions of people, or a Roman Catholic missionary who tended to the poor, matters very much to the victims of totalitarianism and poverty.

Why does it matter? Because we are sentient beings designed by evolution to survive and flourish in the teeth of entropy and death. The Second Law of Thermodynamics (entropy) is the First Law of Life. If you do nothing, entropy will take its course and you will move toward a higher state of disorder that ends in death. So our most basic purpose in life is to combat entropy by doing something extropic—expending energy to survive and flourish. In our evolutionary past, being kind and helping others was one successful strategy, and punishing Paleolithic Stalins was another, and from this we evolved morality. In this sense, evolution bestowed upon us a moral and purpose-driven life by dint of the laws of nature. We do not need any source higher than that to find meaning or morality.

In the end, Nicholas, you will never know for certain that there is an afterlife, but you can take some comfort in knowing that no one else knows either. In the teeth of such uncertainty, how should we live? Here is how I ended Heavens on Earth. I hope it brings you some solace:

Facing death—and life—with courage, awareness, and honesty can bring out the best in us and focus our minds on what matters most: gratitude and love. Gratitude for a chance at life, given the biological reality that those hundred billion people who lived before us were, in fact, only a tiny fraction of the many trillions of people who could have been born but were not. The chance encounter of sperm and egg that led to each of us could just as well have produced someone else, and you would never know it because there would be no you to know. Once born, we are each unique, a concatenation of genes and brains with thoughts, feelings, memories, histories, and points of view that can never be duplicated, here or in the hereafter. Our sentience—yours, mine, everyone’s—is ours alone and like no other anywhere in the cosmos. We are given this one chance to live, some four score trips around the sun, a brief but glorious moment in the cosmic drama unfolding on this provisional proscenium. Given all we know about the universe and the laws of nature, that is the most any of us can reasonably hope for. Fortunately, it is enough. It is the soul of life. It is heaven on earth.

###

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University, the host of The Michael Shermer Show, and the author of numerous books. His next book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational, which you can pre-order here.

Wow. I need to write you a letter. Excellent. Thanks for publishing this.

What a wonderful essay! I wish I could like it twice...