Easter Sunday, April 17, 2022

This morning I posted a series of tweets about the resurrection that in retrospect I fear may have been received as disrespectful or trolling, which was not my intention. Here are the tweets in question (slides from my PPT lecture on religion):

Perhaps, however, such a syllogistic analysis only applies to those who believe that the resurrection literally happened; that is, the raising of the body of Jesus of Nazareth after his crucifixion is an empirical truth. But what if it was never meant to be that type of truth? What if it was meant to be something like a metaphorical or mythic truth, in which readers might be inspired to “bear your own cross” or admonished not to be “crucified” by your enemies, or warned not to “resurrect” bad habits, or encouraged to become “born again” by starting your life anew after a troubling past?

Such mythic, metaphorical, and literary truths play a central role in human culture through the arts, literature, religion, and even politics. Recall that Jesus suggested to his oppressed peoples that redemption was coming, that the Kingdom “has come upon you” (Luke 11:20), and especially in Luke 17:20-21, where Jesus seems to infer that heaven is a state of mind:

“And when he was demanded of the Pharisees, when the kingdom of God should come, he answered them and said, The kingdom of God cometh not with observation: Neither shall they say, Lo here! or, lo there! for, behold, the kingdom of God is within you.”

What if the greatest religious truth in all of Western Christendom—that if you accept Jesus as your savior you go to heaven where you will spend an eternity with God—was never meant to be taken literally? If so, perhaps it illuminates the tantalizing passage in Matthew 16:26 in which Jesus told his disciples…

“Verily I say unto you, ‘There be some standing here, which shall not taste of death, till they see the Son of man coming in his kingdom’.”

Maybe Christians have been misreading passages like this for centuries. Maybe the “kingdom” to which Jesus refers is the heaven within ourselves, or the heavenly communities we build here on Earth. As I wrote in my 2018 book Heavens on Earth:

“Heaven is not a paradisiacal state in the next world, but a better life in this world. Heaven is not a place to go to but a way to be. Here. Now. Since no one—not even the devoutly religious—knows for certain what happens after we die, Jews, Christians, and Muslims might as well work toward creating Heavens on Earth.”

Consider the 1890 Native American Ghost Dance. On the plains of North America there arose a divine savior, a Paiute Indian named Wovoka, who during a solar eclipse and fever-induced hallucination received a vision from God “with all the people who had died long ago engaged in their old-time sports and occupations, all happy and forever young. It was a pleasant land and full of game.” Wovoka’s followers believed that in order to resurrect their ancestors, bring back the buffalo, and drive the white man out of Indian lands, they needed to perform a ceremonial dance that went on for hours and days at a time. This Ghost Dance united the oppressed Indians but alarmed the oppressive government agents, and this tension led to the massacre at Wounded Knee.

Naturally, modern readers do not accept the account of the resurrection of dead Native American ancestors as a literal truth, but what if it was never intended to be treated as such? Consider this interpretation of the Ghost Dance by the anthropologist James Mooney in his 1896 book The Ghost-Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890:

And when the race lies crushed and groaning beneath an alien yoke, how natural is the dream of a redeemer, an Arthur, who shall return from exile or awake from some long sleep to drive out the usurper and win back for his people what they have lost. The hope becomes a faith and the faith becomes the creed of priests and prophets, until the hero is a god and the dream a religion, looking to some great miracle of nature for its culmination and accomplishment. The doctrines of the Hindu avatar, the Hebrew Messiah, the Christian millennium, and the Hesunanin of the Indian Ghost dance are essentially the same, and have their origin in a hope and long common to all humanity.

In my 1999 book How We Believe I called such stories oppression-redemption myths and there are many such examples. The anthropologist Weston La Barre notes that during the colonial domination of parts of Africa by the English, a South Xhosa girl encountered spirit entities while obtaining water at a nearby stream. She told her uncle, who in turn spoke to the deities who informed him that they would help the Xhosa drive the English from the country. In this version, the ritual ceremony that would trigger the English departure was the slaughter of cattle. The girls uncle, Umhlakaza, ordered his tribesmen to destroy all of their herds as well as the granaries of corn. If this ritual was carried out properly, the dead would be resurrected, the old would become young again, illnesses would disappear, herds of fattened cattle would rise from the Earth, and ready-for-harvest millet fields would suddenly appear. Oppression-Redemption.

A similar story unfolded in a Maori village in New Zealand at the end of August, 1934, when a visionary member of the tribe had a dream in which an angel told him that a Holy Ghost would deliver his people from the whites and return their confiscated lands to them. For days following the dream, the Maori fasted, chanted, danced, and waited for the day of deliverance. White administrators got wind of the ceremonies and came to investigate. Finding starving children and deprivation-crazed adults, they declared the visionary insane and shipped him off to a mental hospital. Oppression-Redemption.

My favorite example of the Oppression-Redemption myth is the Cargo Cults of the South Pacific. Most people are familiar with those that arose during and after World War II, but according to the anthropologist Marvin Harris, Cargo Cults began centuries ago with Pacific islanders scanning the horizon for phantom canoes delivering goods. As the times changed so too did the delivery vessels. In the 18th century the Polynesians watched for the sails of sailing ships. In the 19th century they scanned for the smoke from steamships. And in the 20th century they sought the tell-tale signs of airplanes. The cargo also evolved: First it was matches and steel tools, then shoes, knives, rifles, ammunition, and food stuffs like canned meat, and finally it became radios, appliances, and modern tools.

The Ghost Dance leitmotif intertwined with the Cargo Cults in places like Papua New Guinea, where the indigenous peoples built a thatch-roofed hanger, a bamboo beacon tower, an airstrip manned all day by natives wearing simulated uniforms, and even an airplane made out of sticks and leaves. Long dominated by whites who seemed to possess the mysterious power to produce such cargo, the natives envisioned the day when their ancestors would return with cargo for them, along with, in Harris’ description, “the downfall of the wicked, justice for the poor, the end of misery and suffering, reunion with the dead, and a whole new divine kingdom.” Oppression-Redemption.

With this background let’s reexamine the crucifixion-resurrection story as a type of Oppression-Redemption myth. By the 1st century CE the Jewish people were engulfed within the Roman empire and feared for their very existence. The regions around and including Nazareth were ruled by King Herod, who responded with violence to numerous Jewish revolts against their oppressors. By CE 6 Judea was under direct Roman rule.

A youthful Jesus must have been painfully aware of the tensions between his people and their oppressors, as well as the biblical promise of a Messiah who would drive out the Romans and reestablish the Kingdom of God on Earth. By the time of his three-year ministry from CE 27-30, after which he was executed by the Romans, Jesus had codified a new theology and eschatology to sustain his followers. The theologian Burton Mack identified in this new theology three interconnected ideas that arose following Jesus’ death:

1. A perfect society conceptualized as a kingdom. The Jesus people latched onto this idea and acted as if the kingdom they imagined was a real possibility despite the Romans. They called it the kingdom of God.

2. Any individual, no matter of what extraction, status, or innate capacity, was fit for this kingdom and could act accordingly if only one would

3. The novel notion that a mixture of people was exactly what the kingdom of God should look like.

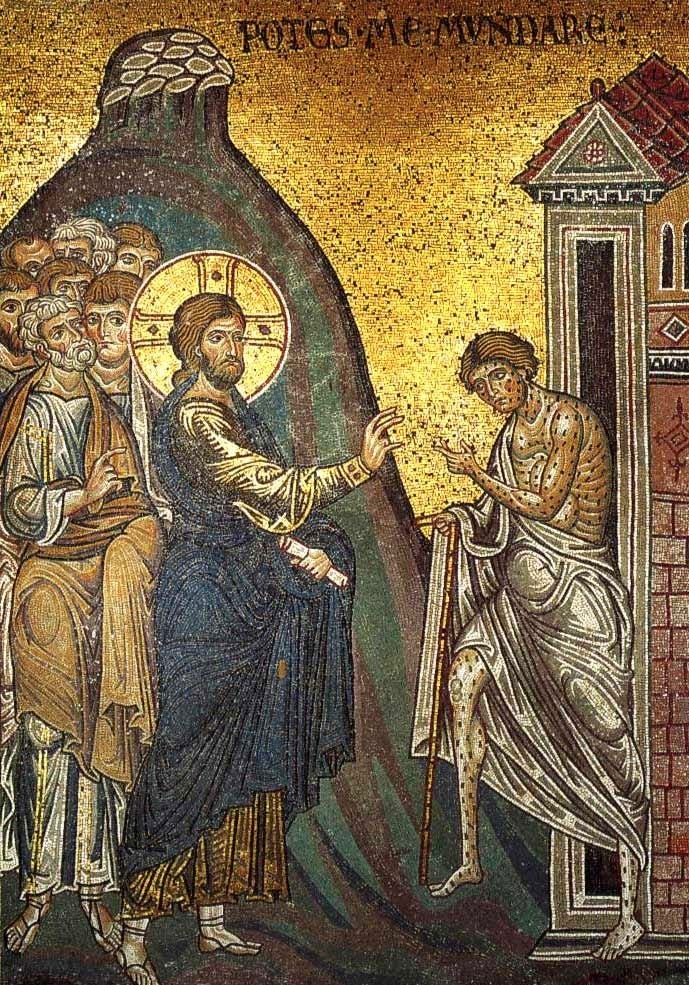

Jesus cleans leper man. Byzantine

Mack concludes that “this was a notion that many groups had used to imagine a better way to live than suffering under the Romans.” Oppression-Redemption.

Who did Jesus and his followers think he was? In Matthew 16:15-16 Jesus asks his disciples “Who do men say that I am?” and they respond “Thou art the Christ.” Christos is Greek for messias, from masiah, Hebrew for Messiah. To many early Christians, the Hebrew Bible spoke to them of a returning Messiah:

“Behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that I will raise unto David a righteous branch, and a King shall reign and prosper, and shall execute judgment and justice in the earth.”

Such prophecies must have been especially reassuring to a people under the yoke. Indeed, Christianity’s founding father, Paul, told the Colossians (1:14): “In whom we have redemption through his blood, even the forgiveness of sins.” To the Hebrews Paul said (9:12): “Neither by the blood of goats and calves, but by his own blood he entered at once into the holy place, having obtained eternal redemption for us.” Redemption was not only for individuals, but for all Israel, as Luke notes (24:19-21):

“Concerning Jesus of Nazareth, which was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people. And how the chief priests and our rulers delivered him up to be condemned to death, and have crucified him. But we trusted that it had been he which should have redeemed Israel.”

Oppression-Redemption.

When social and political conditions include the oppression of an entire people, we should not be surprised when the response comes in the form of a belief in a rescuing messiah delivering redemption. Call it the Messiah Myth. Like all myths, it may be a fictitious narrative, but it represents something deeply true about human nature and history.

It's an interesting view on things, but if you take Mark to be the first gospel you'll notice that from 15:40 on he does only one single thing: put 3 women on stage, 2 of them in a cameo appearance even, with the sole goal to blame them for the fact that no one had ever heard of a dead Jesus rising from the grave

There's nothing more to it than that really

Compare Mark to Luke, and to Matthew, and you'll find that they move away from everything in his story. Luke shifts the blame on the apostles instead, Matthew has Jesus appear straight away to evade the entire blame game

Mark is merely countering Marcion, who highly likely ended around Mark 15:37 / Luke 23:46

I'm aware that Tertullian etc attest to the resurrection, but it would have greatly hurt their case if they hadn't, re docetism

https://www.academia.edu/76105160/The_self_evident_emergence_of_Christianity

“This morning I posted a series of tweets about the resurrection that in retrospect I fear may have been received as disrespectful or trolling, which was not my intention.”

Regardless of your intentions, if you express a view of the alleged resurrection which is outside of the Christian mainstream, then you will be considered disrespectful by Christians, at least most of them. This applies even to the metaphorical view you express here in substack.

“What if it was meant to be something like a metaphorical or mythic truth,...”

But the evidence weighs against that hypothesis. It appears that Paul and the Gospel writers intended their stories to be taken literally.