The Spy Who Came in From the Cold War

A brief history of spies, lies, and intelligence, from Stalin to Putin and from Truman to Trump, by guest columnist Michelle Ainsworth

Review of:

Spies, Lies and Algorithms: The History and Future of American Intelligence by Amy Zegart

Spies: The Epic Intelligence War Between East and West by Calder Walton

Reviewed by Michelle E. Ainsworth

Michelle E. Ainsworth holds an MA in history and has been a regular contributor to Skeptic for many years. She enjoys learning about intellectual history, and is currently researching the cultural history of stage magic in the United States. She is a member of the New York Society for Ethical Culture. She blogs at humanistchick.blogspot.com

“Intelligence failures result from “the natural variations in the predictability of human events and the limitations of human cognition.” —Amy Zegart, Spies Lies and Algorithms

“Western powers can be in a cold war …before they realize it.” —Calder Walton, Spies: The Epic Intelligence War Between East and West

How is the history of espionage relevant to the present? How does recent document declassification change our understanding of the Cold War? Amy Zegart’s Spies Lies and Algorithms broadly and concisely surveys the whys and hows of the US intelligence community from multiple perspectives. Calder Walton’s Spies: The Epic Intelligence War Between East and West deeply surveys a century of espionage by Russia against the US and Britain. Both books offer new information and conclude with sharp warnings for the present.

When I was in graduate school, the professor of a class on the history of the Cold War commented that a book that he had initially assigned had already been rewritten with a new title due to information declassified just after the first one had gone to press. I recalled this often as I read Calder Walton’s Spies, noting that his sources were documents which had only been accessible or declassified as recently as 2022. As such, Walton’s book rewrites history, from Lenin to Putin. Dr. Walton’s thesis is that Russian espionage against the US and Britain was as aggressive before and after the Cold War as it was during it.

Some of the book’s new or strengthened conclusions will please partisans of either side in US debates. Conservatives might take grim validation in the relentlessness and depth of Soviet (and then Russian) espionage. For example, Russian archives have not only proven the guilt of President Franklin Roosevelt’s advisers Laughlin Currie and Treasury Secretary Harry Dexter White (among many others of the Cold War era), but also reveal compelling new evidence of Russian assistance to liberal politician Henry Wallace, as well as to later left-wing intellectuals and the multi-country anti-nuclear movement, and that the Soviet Union used détente (and later the Soviet Union’s collapse) to increase its espionage. Liberals, on the other hand, may be pleased by new evidence that US Cold War policy did not consider Soviet perception of NATO, and that the founding US Cold War document’s “domino theory” was based on a false premise (Kremlin documents now show that Soviets did not initiate wars in the Third World).

Newly released material also suggests that from Lenin to Putin, Russian leaders’ refusal to tolerate criticism and alternative points of view severely damaged the Soviet Union (and then Russia) internally and externally. In contrast, the openness of the US and Britain made it smart for Russia to focus its efforts on human spies. Walton points out, for an example perhaps of particular interest to Skeptic readers, that Russian spies in the US were remarkably successful in their technological espionage, not just in accelerating the Russian development of the atomic bomb, but also of stealing military technology more recently, so that “US science and technology effectively drove both sides of the Cold War.”

One revelation that startled me was new evidence that Truman was never briefed on Korea prior to the outbreak of war, and that throughout the Cold War and since, in Russia and the US most spies who were caught was due to the opposing side’s defectors (and that both sides blundered in promoting people who committed treason). By contrast, Walton argues that, in most other areas, even intelligence historians continue to over emphasize the role of human spies and underestimate the role of communications interception (“signals intelligence”, or SIGINT).

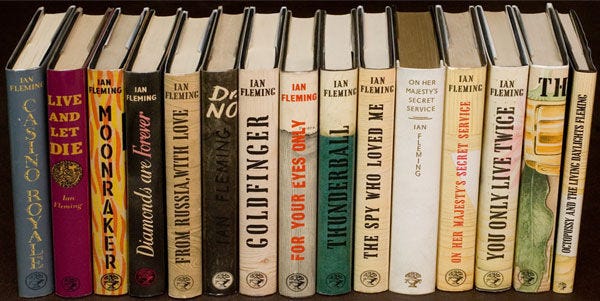

One reason for the overemphasis on human spies highlighted by Professor Amy Zegart in Spies Lies and Algorithms is the explosion in popularity of spy entertainment in recent decades (which she dubs “spytainment”), where individuals save the world. The ticking time bomb scenario is a staple of fiction, but has vanishingly few analogs in real life where, according to Zegart, real intelligence work involves multiple sources weighed against each other.

Walton’s most dramatic example of how both human and technological methods complement one another is new evidence of how and why President Kennedy was able to defuse the Cuban Missile Crisis. But this is not how it is portrayed in fiction. In a point familiar to skeptics in other contexts, Zegart acknowledges how terrific it would be if fantasy were reality, and cites alarming evidence that the general public confuses the two. Her even more damning indictment is that entertainment has been mistaken for fact by senior policy makers in the 21st century, including by a US Supreme Court Justice and in a confirmation hearing for a CIA director.

With both public ignorance of intelligence matters, and in the later chapter on Congressional oversight, Zegart diagnoses the root of the problem as the necessity of secrecy: most current intelligence documents are illegal for political scientists to examine, while older declassified documents sought by historians can arrive years after their request, and even then be heavily redacted. Thus, Zegart finds it unsurprising that there are remarkably few articles about intelligence in academic journals, and incredibly few college courses on the history or politics of espionage. Zegart sees a similar dynamic at work with Congressional oversight, where elected representatives can’t talk about secret material and there is no voting constituency clamoring for information about non-classified intelligence and espionage matters.

As background, Zegart discusses the history of US intelligence, including an additional chapter on highly placed traitors. The heart of the book is a chapter-by-chapter discussion of issues in the world of espionage. Her discussion of what real life intelligence work is (mostly mundane), and what its results can and cannot do, is nuanced and sobering. Skeptic readers will not be surprised by the challenge of overcoming confirmation bias, human frailty at estimating size and probability. Evidence, she suggests, is that such cognitive shortcomings are best overcome by outsider “devil’s advocate type counter-scenario planning,” just one of many stresses of working in intelligence sympathetically told. The paradox of the Presidential use of covert action explains why Presidents of opposing parties, in different times and facing different challenges, all criticize secret, morally questionable “active measures”, but end up using it anyway.

The severity of government sanctioned hacking (such as by Russia against the US) has been in the headlines, so I won’t dwell on her chapter on it here, though she of course gives it scholarly depth, concluding that it poses a greater threat than terrorism.

Walton and Zegart agree that governments are losing their monopoly on intelligence gathering, essentially due to new technology. Zegart sees Google Earth, smart phones, and other public technology as having broken the monopoly that governments (and news media) once had on the discovery of nuclear weapons sites and other military matters, and she discusses the potential dangers premature revelation of that information, even if it is true, poses. Here and elsewhere, she emphasizes that the analysis of images and other data is highly specialized among intelligence professionals, with many traps that even well-meaning amateurs can fall into. Where Zegart focuses on private citizens, Walton sees the future of intelligence as being in multinational private companies, selling satellite access or high-end encryption programs to whatever government or business will pay their prices, and with no chance of government oversight.

Both books cite FBI statistics to show that China is by far the greatest threat to the US via government and business allied intelligence agencies sending a seemingly endless number of highly trained agents to steal military and technological secrets from the US. Both authors also discuss the difficulty and urgency of reorienting an intelligence bureaucracy to new realities. More on point, both authors agree that history and current practice both indicate that intelligence is most effective when multiple techniques—human spying, satellite imagery, and much more—are used in combination, and both authors agree that cuts to intelligence budgets end up costing more than they save.

I should also note that both authors mention the relationship between intelligence and conspiracy theories. First, both mention a few conspiracy theories that were real, including the recent revelation of a Cold War deal with a leading manufacturer of government encoding machines. But people too often see conspiracies where none exist. Part of Walton’s data comes from England, and he suggests that “Those who tend to see…conspiracy overestimate the competency of those in Whitehall.” Zegart quips that from her analysis of the impact of “spytainment” and her survey of Ivy League courses, students are more likely to hear a professor discuss U2 the rock band than U2 the spy plane, one point of which is that ignorance of espionage history and practice is a great breeding ground for conspiracy theories. While Stalin’s paranoia is well known, Walton provides evidence of Lenin’s as well, while concluding that Putin is “a naturally inclined conspiracist.” From the Russian Revolution to World War II and Putin’s attacking Ukraine, Walton concludes that the West doesn’t have a “Putin problem”, it has a Russia problem.

As outstanding as both books are, no texts of such depth can be perfect. The most serious problem with Walton’s Spies is that the bibliography is solely online, and the entries on it do not always include dates and publisher information. Worse, the website has often been inaccessible (though thankfully the book does contain extensive endnotes). In the book itself, if part of Walton’s thesis is that the Cold War started in 1917, shouldn’t he have offered more than one example of early espionage? A subtitle of “Russia and the West” would have been more accurate than its actual subtitle of “East and West.” Recent scholarship in most areas is thorough (based on his endnotes), but at least two books are missing, including G-Man by Beverly Gage (for its new data about FBI work abroad, which I reviewed in Skeptic). Though Walton and Zegart are both good writers, and I don’t usually mind typos or occasional inelegant sentences, each book also has a few substantive sentences the meaning of which are unclear, which should have been caught by a copy editor.

Most of Walton’s 548 pages of main text are well used, but some ancillary material (such as recently declassified World War II British intelligence work unrelated to Russia) might have been edited for length, however fascinating and new it is. I also wonder if, in a work of history, it is best practice for an author to explicitly discuss implications for the present, which he does, with several opening pages on Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine and a closing chapter on the relevance of the book’s conclusions to 21st century Chinese espionage. That said, in two sentences this is telling or at least amusing: for this book, it was discovered that a World War II Russian operative in Ukraine was named Nikita Khrushchev, who might not have become future Soviet leader if he had tried to warn Stalin of German troops massing on the border of Russia prior to the Nazi invasion on June 22, 1941 (Operation Barbarossa). Another likely case of the futility of speaking truth to power in the Soviet Union is the anecdote about a lone high-placed Czech who tried to warn the public about Soviet tyranny but who soon died from falling out a window. Sound familiar?

Elements of the German 3rd Panzer Army on the road near Pruzhany, June 1941.

More to the point, Walton offers two examples of recent or new evidence that the world came closer to nuclear war than previously known, not only during the Cuban Missile Crisis, but, perhaps, also in a 1980’s military exercise that may have been mistaken for the real thing (the 1983 NATO war game exercise called Able Archer 83, that simulated a nuclear attack on the Soviet Union.

A Soviet SS-20 IRBM, on display near the Great Patriotic War Museum

Both resulted in increased dialog between the US and Russia.

President Ronald Reagan’s July 21, 1987 meeting with MI 6 asset double agent Oleg Gordievsky. Wikimedia commons.

It is too early into the Trump administration to know how US-Russian relations will play out, but no doubt that spies, lies, and intelligence will continue to influence international relations.

I like the new website. Unfortunately you still have me listed as a free subscriber instead of paid.

{ must still get round to reading this but i like the tone - please retain me as a free subscriber