The past couple of months of 2024 has to be one of the wildest periods in political history, comparable to 1968 with the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, the announcement by President Lyndon Johnson that he would not run again as his party’s nominee for the highest office in the land, and of course the seemingly endless overseas war in Vietnam. I have already penned two Skeptic columns on the assassination attempt of President Trump, one a brief history of lone assassins and the other comparing the two hypotheses for how it happened—conspiracy or incompetency? In this column, my colleague Kevin McCaffree takes a deeper look into what is behind the apparent chaos of our current politics and the deeper cost of what he calls political pretending.

Dr. Kevin McCaffree is a professor of sociology at the University of North Texas. He is the author or co-author of five books, co-editor of Theoretical Sociology: The Future of a Disciplinary Foundation and series co-editor (with Jonathan H. Turner) of Evolutionary Analysis in the Social Sciences. In addition to these works, he has authored or co-authored numerous peer-reviewed journal articles and handbook chapters on a variety of topics ranging from cultural evolution to criminology to the sociology of empathy. His two books include Cultural Evolution: The Empirical and Theoretical Landscape, and The Dance of Innovation: Infrastructure, Social Oscillation, and the Evolution of Societies. Along with Anondah Saide, he is one of the two chief researchers for the Skeptic Research Center, and I had the honor of serving on his dissertation committee for his Ph.D. thesis on the rise of the Nones—those who hold no religious affiliation.

The Social Cost of Political Pretending

By Kevin McCaffree

Former president Donald Trump narrowly survived an assassination attempt on July 13th 2024, and though the media’s attention has mostly focused on Trump, it was Corey Comperatore who lost his life trying to shield his family from flying bullets. In response, President Joe Biden, former President Barack Obama, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, former speaker Nancy Pelosi, Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and many mainstream journalists—from MSNBC anchors to the New York Times editorial board—were quick to express their concern for Trump in the wake of the shooting.

Biden was “grateful” that Trump was safe and was “praying for him.” Obama and Schumer were both “relieved” that Trump hadn’t been seriously hurt, Pelosi thanked God “that former President Trump is safe,” and Ocasio-Cortez rushed to Twitter to wish Trump a “speedy recovery.” The New York Times editorial board announced they “hope Mr. Trump recovers quickly and fully,” and among others, MSNBC anchor Chris Hayes quickly offered his condolences, saying he was hoping for Trump’s “swift recovery.”

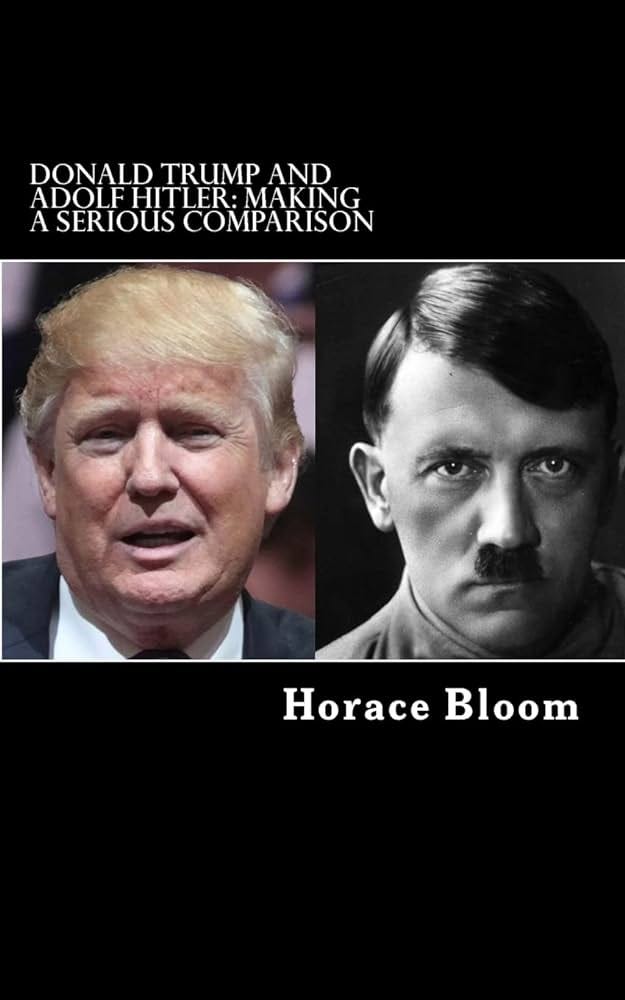

Though heartening, this outpouring of sympathy for Trump is an odd reversal of the rhetoric leading up to the assassination attempt. About two weeks prior to the assassination, President Biden insisted that Trump was a “genuine threat” to the nation, a “threat to our freedom,” a “threat to democracy,” and “literally a threat to everything America stands for.” This had become a consistent slogan of Biden’s re-election campaign. In fact, a few months prior, Biden’s official promotional account on Twitter directly compared Trump to Adolf Hitler, the German dictator who was responsible for the deaths of tens of millions of people from 1933-1945. And, apparently, among Biden staffers, Trump’s nickname is “Hitler Pig.” (The above image is from the Washington Post and the one below is from The Telegraph, both mainstream newspapers read by millions.)

This portrayal of Trump as a violent and dangerous fascist akin to Hitler—an existential threat to the country—is not new. In her 2016 campaign for president, Hillary Clinton described Trump as “dictatorial” and “authoritarian,” noting that even if Trump was duly elected we must remember that “Hitler was [also] duly elected.” After Trump was elected, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez alarmed the public with reports that Trump was building “concentration camps” along America’s southern border. She’d insisted she wasn’t “using those words lightly,” but was earnestly reporting that Trump had begun building actual concentration camps in America.

Journalists were quick to support and spread this rhetoric. A few months before the assassination attempt, the New York Times editorial board stated unequivocally that Trump was “dangerous in word, deed and action.” MSNBC anchor Chris Hayes regularly suggested that a Trump presidency would “destroy” democracy and that Trump would likely “act with near-total criminal impunity” if given a second term in office. Hayes’ colleague, Joy Reid, has made it something of a personal mantra to refer to Trump as Hitler.

And, of course, university professors, for their part, have long painted Trump and his supporters as racists and fascists. A full accounting of the descriptions of Trump as a Hitler-esque figure could fill many more columns here.

The absurd, but powerful, conclusion to draw from this is that Thomas Matthew Crooks, Trump’s would-be assassin, may well have been operating with bounded rationality, with genuinely moral intentions, believing Trump to be, as he was told by the elites in his society, the second coming of Hitler. Crooks was a young adult who had spent no time cavorting in the shiny halls of congress, academia, or J schools. He may well have been a delusional schizophrenic, but the fact that our elite discourse was consistent with his actions should be a wakeup call. Let’s consider this problem a little deeper.

The Thought Experiment

A well-tread thought experiment in popular culture is to consider the ethics of killing baby Hitler. The thought of murdering a child is rightly regarded as abhorrent, but what if that child were Adolf Hitler? Then would it be justified? Tens of millions of people might plausibly be saved. In the runup to the 2016 election, even beloved actor Tom Hanks opined that, should a presidential candidate be able to invent such a time machine, “I am going to vote the pro-going-back-in-time-killing-Hitler ticket!”

Who could blame him? It is a genuine moral dilemma: (1) killing babies is morally wrong, however, (2) killing Hitler would have been a net moral good. It is a dilemma because we can all agree on proposition (1) as well as on proposition (2), though their combination introduces a moral approach-avoidance conflict. But suppose this modern Hitler wasn’t a baby? Suppose Hitler was running for president in America in 2024. Then would it be wrong to kill him? Wouldn’t we face a moral obligation to do so?

Thus, it is necessary to state that Donald Trump is not Adolf Hitler. He might fairly be regarded as odious in personality, impulsive in behavior, and wayward in his policies. But there is zero credible evidence that he is a white supremacist (his supposed racism as evidenced by the “very fine people on both sides” Charlottesville speech has been debunked endlessly and he condemned white supremacists over thirty times in his presidency) or that he built concentration camps.

Whether Trump is an existential threat to democracy seems to hinge on his reluctance to accept the results of the 2020 election. We should all agree that his reluctance was ill-advised, but what motivated it? If you ran for re-election as President and most of the mainstream institutions in your country—from journalism to entertainment to academia—worked tirelessly to oppose you as some deranged second-coming of Hitler, would it be completely irrational to suspect some kind of election malfeasance?

The point is not that Trump was correct to denounce the election results—the election was fair and Trump legitimately lost—the point is that a charitable interpretation of his behavior is that he was defiant and exhausted from the attacks against him. Not the second coming of Hitler, but rather, a prideful man who accurately perceived the social influence of the many mainstream institutions working daily to skewer him in the most exaggerated way possible. And the bevy of lawsuits and charges against him since the 2020 election has only accentuated the problem.

The Politics of Pretending

Politicians, journalists, academics and other cultural elites take for granted that the public knows what they know, namely that politics is a playful theatre for them to be naughty to each other in pursuit of popularity points. It is a luxury to be able to internalize the fact that politics, journalism, and academia is often a world of pretend, a sphere of make-believe. Internalizing this process is a marker of social status, a sign that one has spent time in the hallowed halls of congress or academia or media. It is a signal one sends indicating you know that such political discourse doesn’t really, and isn’t supposed to, map onto actual reality. Wink, wink, nudge, nudge.

The average American who works a real job and takes care of a real family, relies on politicians, journalists, and academics to tell the truth, to be honest, to describe one another with a modicum of accuracy. When most Americans try to learn about this or that political issue, they might not take for granted that politicians are just pretending, just playing. Perhaps they’d have had to waste time in graduate school, or in journalism circles, or seeking celebrity status in L.A., or have canvassed for a politician, to fully recognize the depth of make-believe.

Unsurprisingly, amidst this onslaught of pretending, political polarization in the public has steadily increased. “Affective” polarization, or emotional coldness towards those perceived as having opposed politics, is reaching some of its highest levels ever measured in the public (despite the fact that, ironically, on the actual issues, people don’t differ much).

There is plenty of pointless debate over whether this polarization was sparked by liberal elites (think “defund the police,” “Abolish ICE,” “smash capitalism,” and, of course, “Trump is Hitler”) or by conservative elites (think Bible study in public schools, calls for full abortion bans, or Trump’s overturning of Roe v. Wade). Finger pointing in this way misses the deeper issue. Polarization occurs in a feedback cycle, so whichever political party “started it” is less important than the reciprocal extremism which builds in response to one another’s most outlandish excesses.

The Social Cost of Political Pretending

Children pretend because pretending is a fun form of play. They engage in make-believe as a way to let loose, connect socially, and explore freely. Pretend and make-believe are entertaining and constructive for children because the stakes are low and the only consequence is unanticipated fun or hilarity.

In this way adults play too, and play a bit too much, when they find themselves in occupations that require minimal accountability, afford maximal social status, and allow for substantial distance from the everyday public. The only problem is that when these adults play, the stakes aren’t always low and the consequences can be severe. Over time, as politicians and others play make-believe in their official capacities, a number of things happen:

They lose their legitimacy in the eyes of the public.

Political discourse takes on an air of superficiality and uselessness.

Young people become disillusioned and disinterested.

The public becomes prone to misinformation and conspiracy theories.

Our national sense of unity falls apart.

Affective polarization increases and even families begin to dissolve (yes, really: politically polarized family members avoid contact with loved ones with whom they disagree).

Trump will not be the last president to be the target of an assassination attempt—given the sad reality of mental illness, such political violence will never fully disappear regardless of public policy, or improvement to our discourse, that we might pursue. But, at a minimum, our cultural elites can stop playing pretend with our national political discourse. Or, at a minimum, the public might finally accept that to be a cultural elite is to be sheltered, coddled, enabled, and incentivized to play, play, play, like Peter Pan with a graduate degree.

This opinion peice is mostly nonsense. Take this paragraph:

"Whether Trump is an existential threat to democracy seems to hinge on his reluctance to accept the results of the 2020 election. We should all agree that his reluctance was ill-advised, but what motivated it? If you ran for re-election as President and most of the mainstream institutions in your country—from journalism to entertainment to academia—worked tirelessly to oppose you as some deranged second-coming of Hitler, would it be completely irrational to suspect some kind of election malfeasance?"

Would it be irrational to suspect election malfeasance? Yes. If all evidence led to the conclusion that there was virtually no malfeasance—as the evidence showed in the 2020 election—it would be completely irrational to claim fraud—as Trump relentlessly did (and continues to do.)

And were all "mainstream institutions" (whatever they are) working tirelessly to oppose him? I guess it needs to be pointed out that the most popular news channel in America, Fox News, worked tirelessly to support him, as did popular blogs, podcasts and Twitter accounts.

Further, weren't thoughtful people correct in opposing him? That was clear four years ago and even more clear now. Sam Harris summed it up perfectly last week on Substack:

"No one has done more to destroy civility and basic decency in our politics than Donald Trump. No one, in fact, has done more to increase the threat of political violence. Unlike any president in modern history, Trump brings out the worst in both his enemies and his friends. His influence on American life seems almost supernaturally pernicious."

Comparing Trump to Hitler is probably over the top, although J.D. Vance did it privately four years ago. On the other hand, the hypothesis that Trump is an existential threat to our traditional liberal democracy is valid and supported by the facts.

Some good points, but I can't take a lot of it seriously. There is "charitable" and then there's believing in unicorns. Even if Trump had honest suspicions about the election's integrity, those doubts should have been alleviated by the outcomes of over 60 court cases that found no evidence of widespread fraud. Furthermore, several members of his own administration and party, including William Barr, Chris Krebs, Mark Meadows, Mitch McConnell, Dan Coats, etc., affirmed that the election was fair and that Trump lost. Additionally, the fake elector scheme, asking Raffensperger to find votes, and the attempt to interrupt the certification of the Electoral College votes with a mob, aiming to throw the election back to the House, demonstrate a clear intent to hold on to power and a complete disregard for democratic processes; both of which, by definition, are a threat to democracy. To imply there were no legitimate grounds to call out Trump's illiberal impulses is the definition of "pretending." True, Trump isn't Hitler, but by this logic, even Hitler could charitably be said to have just been a dedicated summer camp organizer.