Was the Great Scientist E. O. Wilson a Racist? NO!

Because Wilson corresponded with the notorious race differences psychologist Phillippe Rushton, critics claim it proves Wilson was a racist. Here’s why the critics are wrong, dangerously wrong

“To keep the record straight, I am happy to point out that no justification for racism is to be found in the truly scientific study of the biological basis of social behavior.”

—Edward O. Wilson, Nature, February 19, 1981, Vol. 289, p. 627

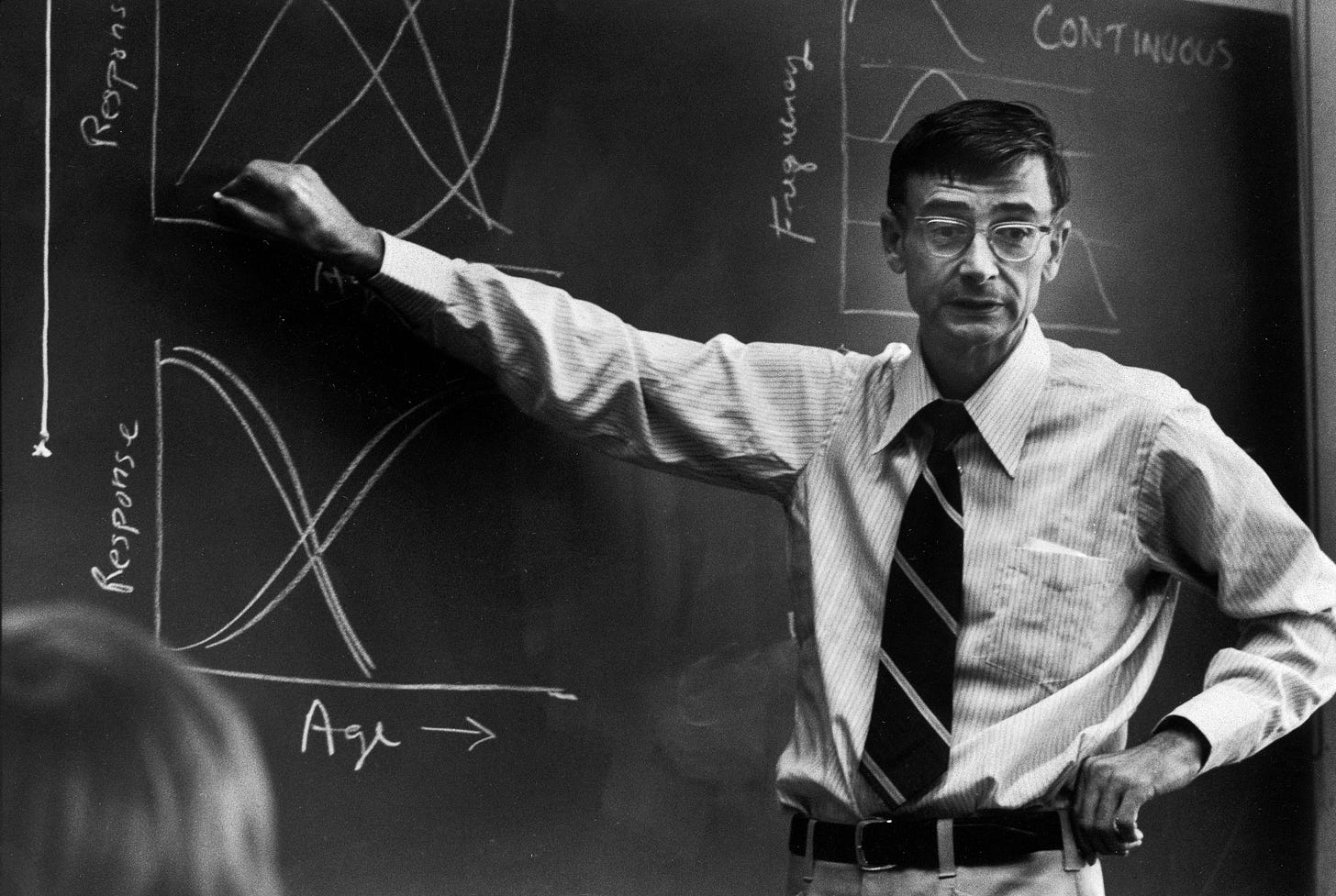

Sociobiologist Edward O. Wilson teaching class at Harvard University. (Photo by Hugh Patrick Brown/Getty Images)

On December 26, 2021, the renowned Harvard University evolutionary biologist, conservationist, and two-time Pulitzer Prize winning writer Edward O. Wilson died at the age of 92. Three days later Scientific American, for which I penned a monthly column for nearly 18 years, opined on “The Complicated Legacy of E. O. Wilson” through the voice of Monica R. McLemore, who with no engagement with any of Wilson’s scientific theories announced that “we must reckon with his and other scientists’ racist ideas if we want an equitable future.” No examples of said racism were provided. She even branded as a racist Gregor Mendel—the 19th century scientist who established the role of genetics in pea plants—although there is absolutely no evidence for this extraordinary claim, unless it is racist to demonstrate that pea color is genetically determined.

Shortly after that hit piece, the publication Science for the People, whose website self-describes as “an organization dedicated to building a social movement around progressive and radical perspectives on science and society,” declared that it has “new evidence of E. O. Wilson’s intimacy with scientific racism.” The charge is not new. In 1975 this same group accused Wilson of promoting race science and eugenics upon the publication of his book Sociobiology, which viewed all creatures—including humans—as biological beings, part of evolved life on Earth. In the final chapter Wilson argued that human capacities for culture and behavior, including aggression and xenophobia, along with altruism and love, are facilitated by biological capacities.

The ensuing “sociobiology wars”, as the science historian Ullica Segerstråle characterized the conflict in her 2001 book Defenders of the Truth, erupted when Wilson’s Harvard colleagues Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin launched their Sociobiology Study Group through Science for the People. Opening salvos against Wilson appeared in the New York Review of Books, culminating in the now notorious incident at the 1978 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C. When Wilson advanced to the podium to speak demonstrators chanted “Racist Wilson you can’t hide, we charge you with genocide!” Someone leapt up on the dais, grabbed a cup of water, and dumped it on Wilson’s head, shouting, “Wilson, you are all wet!” This was too much even for Gould, who remonstrated the demonstrators, telling them their actions were what Lenin had dismissively called “Infantile Leftism.”

The critics’ strategy ultimately backfired because Wilson never said anything to suggest racial superiority. Still, based largely on the attacks by Gould and Lewontin, some people conflated Wilson’s discourse on the biological roots of human behavior with racist ideas. In response, Wilson took pains to explicitly denounce those claims. He said, explicitly, that racist pronouncements find no support in biology (see the epigraph above and the ending below). For decades, until his death, Wilson’s clarification sufficed. But since he can no longer defend himself, the critics are back reiterating the same accusations, now purportedly bolstered by a correspondence Wilson carried on with a Canadian psychologist named J. Philippe Rushton, whose research on racial group differences ignited a firestorm in the 1990s. In fact, the tranche of unpublished letters between Wilson and Rushton was donated to the Library of Congress by Wilson himself, including letters that critics purport demonstrate he was a racist and promoter of race science, a peculiar thing to do if one is actually a racist trying to cover over one’s tracks.

The controversy surrounds Rushton’s application of Wilson’s r/K selection theory. In a nutshell, r-selected species produce many offspring, each of which has a relatively low probability of passing on their genes into the next generation, so parental investment is low but with enough opportunities, particularly in less-crowded ecological niches, some offspring will survive and reproduce. K-selected species have fewer offspring and the parents invest more in each. Characteristics of r-selected species include high fecundity, early maturity onset, shorter generation time, and low parental investment. K-selected species have lower fecundity, later maturity onset, longer lives, and high parental investment, a strategy generally required in more stable environments. The distinction can apply to individuals as well as species and has been rigorously debated in the scientific literature, mostly regarding nonhuman species. For example, see this analysis of guppy fish by David Reznick, Michael J. Bryant, and Farrah Bashey in the journal Ecology.

But Rushton didn’t apply Wilson’s r/K selection theory to guppies; his subjects were human racial groups, which he first addressed in a 1985 paper in the journal Personality and Individual Differences (“Differential K theory: The sociobiology of individual and group differences”) and then the full-throated version in a 1994 book titled Race, Evolution and Behavior. Again, to oversimplify, Rushton argued that while all humans are K-selected, some are more K-selected than others, suggesting that Blacks lean more toward r-selection compared to Whites and especially to Asians. This is why he called it “Differential K theory.” The implications were that Blacks are more promiscuous, have more babies, allocate fewer parental resources in each, develop sexual maturity earlier and, as if that wasn’t enough to ignite a radioactive cultural China Syndrome, are less intelligent and have longer penises, compared to Whites in the middle and Asians at the top (with, again, correspondingly higher intelligence and shorter penises). So incendiary was Rushton’s research that the Ontario Provincial Police were called in to investigate and his university launched an investigation, as evidenced in this newspaper clipping (also in the Wilson archives).

I well remember the Rushton affair as it unfolded—with everything from student protests at his university to death threats—and I too just assumed that anyone making such a case must surely harbor unconscious racist propensities, if not overt bigotries. And Rushton didn’t help his case when, long after his correspondence with Wilson, he wrapped up his career with a stint as the director of the Pioneer Fund and wrote articles for Mankind Quarterly, both of which fund and publish (respectively) the study of race differences in intelligence, among other incendiary topics. In a 1995 issue of Skeptic magazine with a special section dedicated to the claims made in Charles Murray’s and Richard Herrnstein’s book The Bell Curve, I equated Rushton’s theory with the “19th century pleadings for racial supremacy and the White Man’s Burden,” and his affiliation with Mankind Quarterly as highly suspect given that one of the early editors of that journal, Roger Pearson, at one time claimed that he’d help hide Josef Mengle after the war, and fantasized about the formation of a Fourth Reich for the benefit of “Pan-Nordicism.” There’s much more to Philippe Rushton’s life and ideas, but this should be enough to make the point that anyone wishing to engage with—much less defend—Rushton, risks being tarred by association.

Which is exactly what was done to Ed Wilson in a recent New York Review of Books exposé by Mark Borrello and David Sepkoski, telegraphically titled “Ideology as Biology.” The authors claim that their interpretation of the correspondence leaves unresolved “the question of whether Wilson espoused racist ideas.” Although Borrello and Sepkoski don’t call Wilson a racist directly, the charge by association with Rushton is unmistakable. And their insistence that Wilson not be “canceled” echoes the opposite of their intentions, inasmuch as they well know that in the current cultural milieu of sensitivity about all matters related to race what would happen. Indeed, the immediate response to that article was calls for Wilson’s cancelation, including by that of a conservation organization that bears his name—the E. O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation—whose President and CEO promptly issued a statement that even though they had not reviewed the Wilson-Rushton correspondence, they nevertheless denounced their founder’s correspondence with and support of Rushton to be “hurtful and harmful” and part of “the insidious effects of systemic racism” and they welcome “robust examination and reflection on the legacy of E. O. Wilson.” I am told that another major environmental organization was about to bestow a posthumous award to Wilson but is now thinking of withdrawing it after reading the NYROB article.

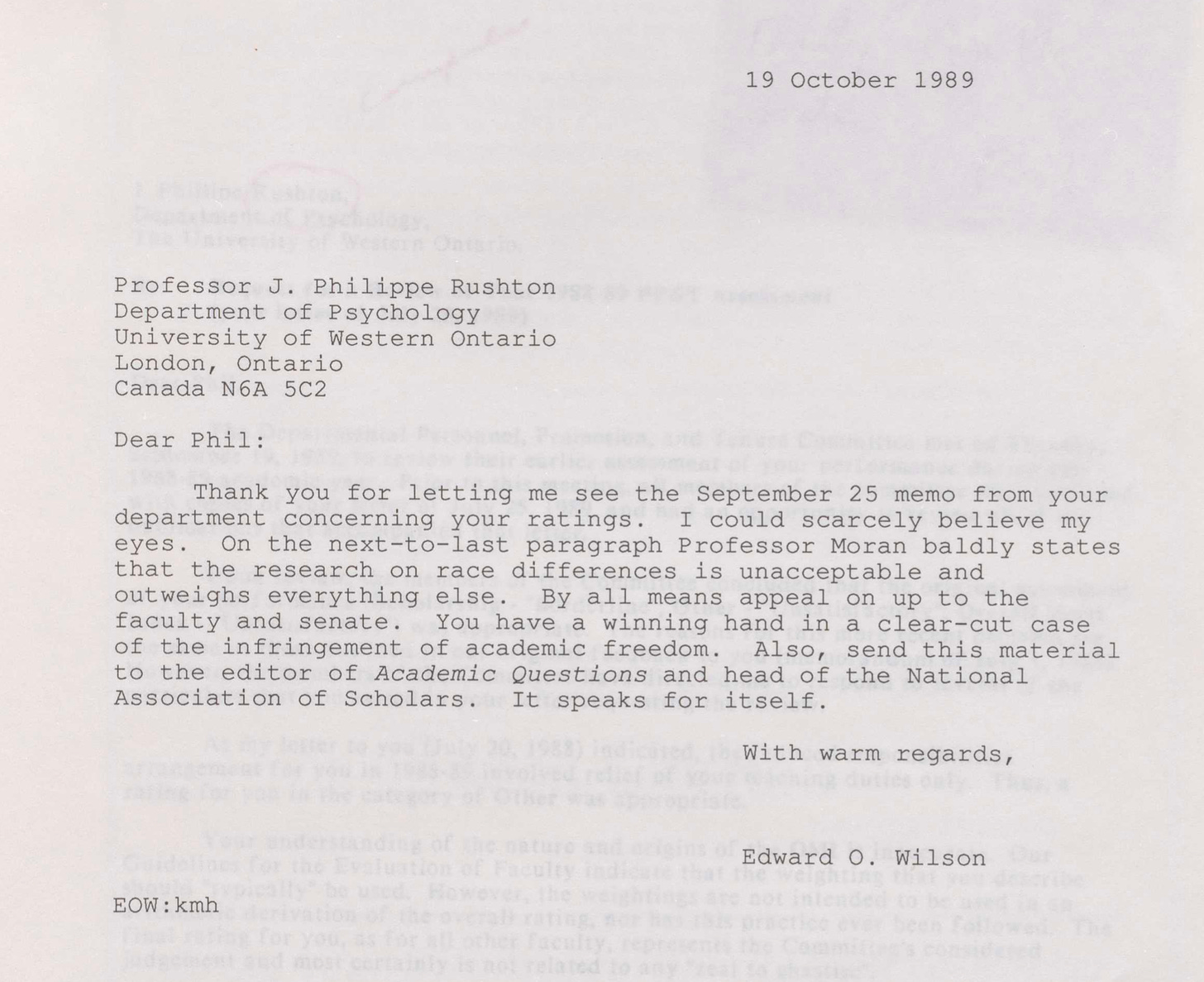

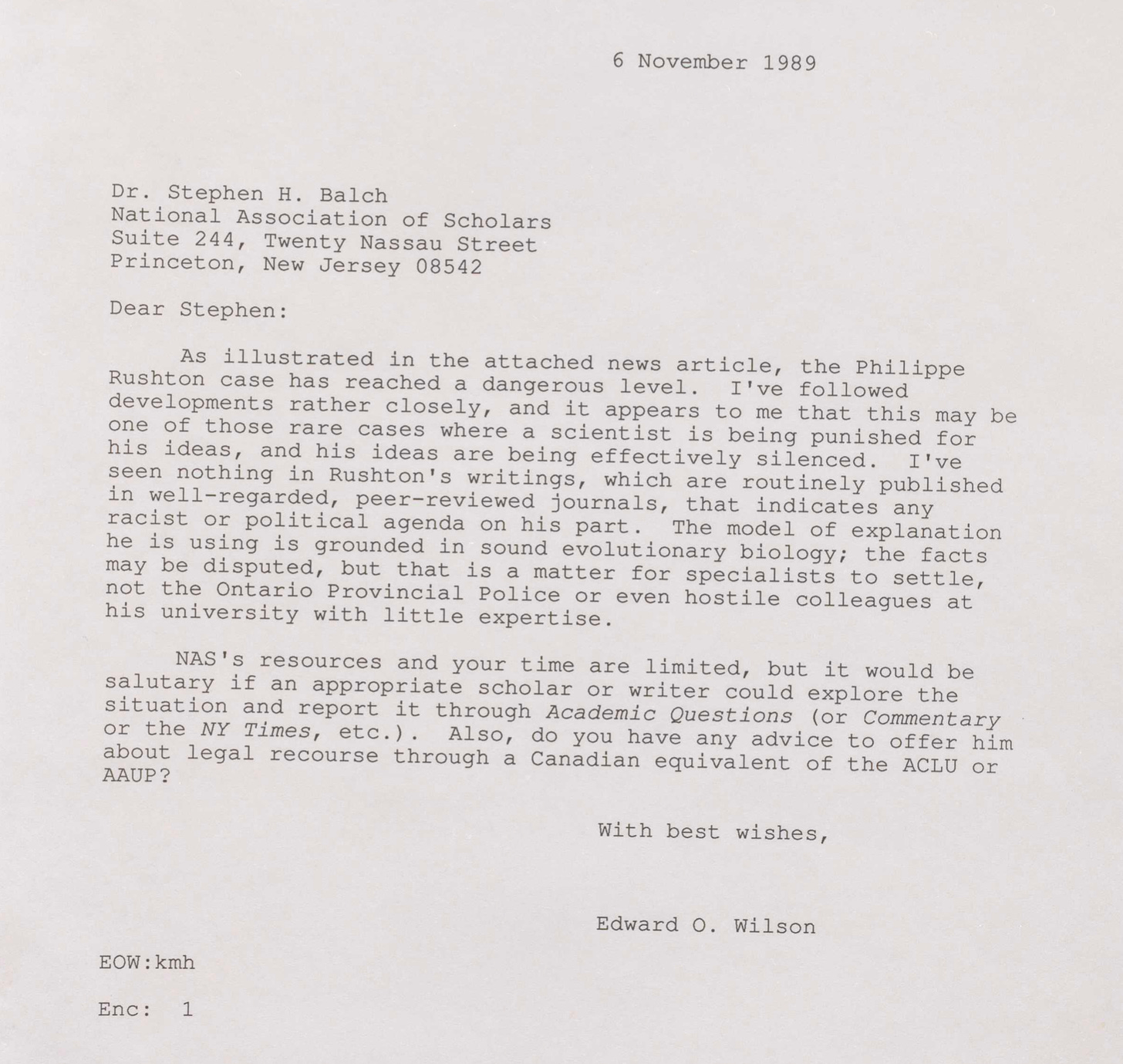

As for the correspondence itself, Borrello and Sepkoski conspicuously fail to reproduce even one of these letters in their article, nor do they provide any lengthy indented quotes by either Wilson or Rushton to give readers a sense of the context of the snippets of letters from which they quote. Nor do they situate any of the letters in the environment of the times, which as we shall see matters very much in assessing the inner motive of the man. At my request the Library of Congress sent me copies of many of these letters, the most important of which I reproduce in full below so you can judge for yourself if Wilson was corresponding with Rushton because he was a closeted promoter of race science (or worse), or because he actually believed in academic freedom and the autonomy to pursue a line of research wherever it may lead. A thorough reading of the Wilson-Rushton correspondence makes it abundantly clear that it is the latter. For example:

19 October 1989, Wilson to Rushton:

You have a winning hand in a clear-cut case of the infringement of academic freedom. Also, send this material to the editor of Academic Questions and head of the National Association of Scholars. It speaks for itself.

6 November 1989, Wilson to Stephen H. Balch, National Association of Scholars:

I’ve followed developments rather closely, and it appears to me that this may be one of those rare cases where a scientist is being punished for his ideas, and his ideas are being effectively silenced. I’ve seen nothing in Rushton’s writings, which are routinely published in well-regarded, peer-reviewed journals, that indicates any racist or political agenda on his part. The model of explanation he is using is grounded in sound evolutionary biology; the facts may be disputed, but that is a matter for specialists to settle, not the Ontario provincial Police or even hostile colleagues at his university with little expertise.

5 December 1989, Wilson to Rushton:

Much as they like, your critics simply will not be able to convict you of racism; and there will come a day when the more honest among them will rue the day they joined this leftward revival of McCarthyism. Like you, I am astonished that so many of our colleagues are staunch defenders of academic freedom until their own beliefs are threatened. Academic freedom means academic freedom--period.

As for Rushton’s application of r/K selection theory to humans, in a 1 March 1990 letter to John B. Conway, Editor of the journal Canadian Psychology, Wilson affirmed his conviction that “Rushton’s concept of applying r/K strategy theory to human biology is sound.” Which is not to say that Wilson agreed with it; only that the approach, which is now a legitimate field of biological research called “life history studies,” is not automatically disqualified because some readers may not like the implications, about which Wilson has elsewhere been clear has no place in justifying racism.

When Rushton’s employer—the University of Western Ontario (now Western University in Canada)—investigated him for academic misconduct, Wilson wrote to them in April of 1990 to let them know that Rushton’s ideas were “sound, being adapted in a straightforward way from well documented principle of r/K selection in biology,” adding that other unnamed biologists agreed. “You may wonder why almost none have published their opinions,” Wilson asked rhetorically. “The answer is fear of being called racist, which is virtually a death sentence in American adademia [sic] if taken seriously. I admit that I myself have tended to avoid the subject of Rushton’s work, out of fear.”

Not all scientists in support of academic freedom remained unnamed. A folder in the Wilson archives titled “On Rushton, Race and Academic Freedom: Responses from the International Academic Community,” includes letters from 45 distinguished scholars and scientists who wrote Rushton’s university to support his appeal of the “misconduct” charges. The pantheon is a veritable Who’s Who of the fields related to Rushton’s work and include the following excerpts from four of the most notable scientists who emphasize the importance of academic freedom in the pursuit of truth.

11 April, 1990, Thomas Bouchard, University of Minnesota:

It is my opinion that had Prof. Rushton published the same number of papers of equal or even lesser quality in any other area of psychology, his performance would have been rated as outstanding. … The issue here is not whether Prof. Rushton’s theory is true. No theory is true and his theory will either fall or be significantly modified in the very near future, as almost all theories are. The issue is: Will this work advance our understanding of the very serious and complex issues that he has addressed? My answer to that question is: Yes, it will. … The freedom to speak and to write about unpopular ideas is the most cherished value of intellectual institutions. In modern western societies it is the defining characteristic of such institutions. Only when the rights of those who propound unpopular ideas are protected do we really now that an institution is committed to the ideal of intellectual freedom.

4 April, 1990, I. Eible-Eibesfeldt, Max-Planck Institute:

I think it is a business of the scientific community to discuss and correct views on the basis of new data. That is the only way science proceeds, and if we want to survive on our planet, we need knowledge. I do not think that it is a matter of a faculty to put pressure on a person when he discusses issues considered as taboo to the prevailing ideology. Criticism has to come from the scientific community, and in particular from experts in the field.

10 April, 1990, James Flynn, University of Otago:

I was raised in an ethnically divided area and early developed a burning hatred of the racial prejudices that set Irishmen like myself, against Italians, against Hispanics, against blacks. … I have never relented in my commitment and am author of my own University’s policy of affirmative action in favour of our Polynesian minority and have earned the enmity of some thereby. I know how bitterly disadvantage groups resent implications that they are genetically inferior for valued human traits. … Despite the fact I disagree with Rushton’s conclusions, I would unhesitatingly rank his contribution on racial differences as above the norms that prevail among current social scientists. He has shown enormous energy in amassing a wide array of facts concerning racial differences, I have never caught him out in a clear error of fact or citation (and I’m very good at this), he has shown wide competence in mastering material from a variety of specialties, and he has developed a coherent theory to order his facts. His theory is challenging and scholarship can only benefit from the task of trying to refute him.

11 May, 1990, James Q. Wilson, UCLA:

Serious research on politically controversial topics is risky and hence scarce. It is the function of the university to bend over backwards to insure that people who engage in such research in a responsible manner are protected, not penalized.

The point is that if you refuse to protest the censorship of people whom you consider obnoxious, it will be harder for you to protest the censorship of people whom you admire but whom others consider obnoxious. The ACLU’s 1977 defense of the right of neo-Nazis to march through Skokie, Ill., a Chicago suburb full of Holocaust survivors, stands out as the paradigmatic case of principle over politics. And, in the end, pace Martin Niemöller, if you don’t protest, when they come for you who will speak out?

The letter from James Flynn is especially poignant in this context as he is the discoverer of the eponymous “Flynn Effect”—that IQ scores have been increasing on average about three points every ten years for nearly a century—a discovery he says he made by reading and refuting Arthur Jensen’s research on race and IQ, in which Jensen argued that Blacks score lower than whites on IQ tests largely because of genetic differences. Flynn attributes race differences in I.Q., along with the broader Flynn Effect, to environmental causes. Nevertheless, in an article on “Academic Freedom and Race” in the Journal of Criminal Justice, Flynn wrote:

There should be no academic sanctions against those who believe that were environments equalized, genetic differences between black and white Americans would mean that blacks have an IQ deficit. Moreover, research into this question should not be forbidden. This is so, no matter what the outcome of the race and IQ debate, that is, no matter whether the evidence eventually dictates a genetically caused deficit of nil or 5 or 10 or 20 IQ points.

What if it turns out that the primary cause of racial differences in IQ is the environment, but because of academic censorship of sensitive topics the only people doing research in this area are those who believe that all such differences are to be found in our genes? “There will be bad science on both sides of the debate,” Flynn admits. But “The only antidote I know for that is to use the scientific method as scrupulously as possible.”

Ed Wilson believed that science should be conducted honestly and without fear. And, as the April 1990 letter reveals, Wilson well knew the consequences of being labeled a racist, so here another hypothesis presents itself: Wilson supported Rushton not out of heretofore hidden or implicit racist proclivities or eugenical propensities, but out of sympathy for a fellow academic whose freedom to conduct scientific research was being threatened. Still, the hostile climate of such an association challenged even Wilson’s good will. When Rushton asked Wilson to sponsor an article he wrote for publication in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), for example, which at the time required membership support for such submissions, Wilson demurred, explaining:

You will recall that I’ve been called a racist (incorrectly, and unjustly) simply because of genetical arguments in Sociobiology, and on one occasion was physically attacked by a group of leftist brownshirts, the International Committee Against Racism. I have a couple of colleagues here, Gould and Lewontin, who would use any excuse to raise the charge again. So I’m the wrong person to sponsor the article, although I’d be glad to referee it for another, less vulnerable member of the National Academy if you locate one as a possible sponsor.

That’s it. That’s the worst of the Wilson-Rushton affiliation. Far from indicting Wilson as a racist, a properly contextualized reading of this correspondence—which responsible journalists and historians of science normally practice when unencumbered by ideology—exonerates Wilson from these calumnies hurled against his posthumous reputation. That is the assessment also made by the distinguished science writer Richard Rhodes, whose biography, Scientist: E.O. Wilson: A Life in Nature, required years of detailed research on Wilson. Here is what Rhodes told me when I queried him on this matter:

Ed wasn’t racist. More than most people, because he grew up in a racist society, he was aware of what that word means. He was, however, someone who encouraged people to pursue lines of research that might lead to breakthroughs, however unexpected or politically incorrect. He was especially eager to see research that might support his work on sociobiology. I suspect that’s why he encouraged Rushton—very carefully, if the NYRB quotes are accurate. He was as well, in those days, to use his own words, “politically naive.”

I also queried the University of California, Berkeley historian of science Frank Sulloway, who studied under and worked with Ed Wilson, and who penned a tribute to Wilson in Skeptic. Here is Sulloway’s assessment on L'affaire Wilson-Rushton:

It is exceedingly easy, without taking in the full historical and interpersonal context (Ed’s vision of applying evolutionary theory to human behavior, which was under attack) and the numerous attacks that Ed experienced personally (which essentially alleged that the mere application of evolutionary theory to human behavior was racist), to see all this new information as being very damning. But Ed was clearly coming to the defense of someone he thought had the right to consider where theory can take one in the study of human behavior, and the right to at least propose and test hypotheses whether they are socially acceptable or not.

Ed may be guilty of being rather naive in how far to go in supporting someone like Rushton, but this was part of Ed’s personality and nature—he was a very generous and enthusiastic person. Hence, I too don’t see any real racism here, unless something more concrete emerges, which—having spoken to people who knew Ed Wilson well—I doubt could possibly be the case. I also don’t think one can expect Ed to have understood in the 1990s the various research flaws that have been revealed in some of Rushton’s work during the three decades since that time. It is the nature of science that many theories, seemingly having strong support to begin with, later turn out to have been mistaken.

Because the scientific study of race differences has a history of being fueled by pseudoscientific bias in a search for justifying claims of white superiority, it may seem axiomatic that science should never touch the topic. But it is the objective study of the question of differences that has actually found biological unity among the human family, no basis for claims of racial superiority, and no justification for oppression. Science is what provides the most irrefutable biological bedrock evidence for rejecting racism. Ed Wilson knew this—and wrote of this—long before he supported Rushton.

Another student and colleague of Wilson, Mark Moffett (who also authored a tribute to his mentor and colleague in Skeptic), pointed out to me that assertions that Wilson was a racist ironically target the very man who first dismantled the legitimacy of race as a meaningful biological category in a 1953 paper titled “The Subspecies Concept and Its Taxonomic Application.” After that, Wilson never used race (or other within-species labels such as subspecies) when describing new organisms. And, in another irony, one of the two principal critics of Wilson’s sociobiology program—Richard Lewontin—wrote in an often-cited 1972 paper, “The Apportionment of Human Diversity,” that “Since such racial classification is now seen to be of virtually no genetic or taxonomic significance…no justification can be offered for its continuance.” In fact, Lewontin here is simply mouthing the conclusions that Wilson had put forward nearly two decades earlier. Indeed, it should come as no surprise that in a department, and an academic subject—ecology and evolutionary biology—that for decades has overwhelmingly attracted whites, Wilson took under his wing Hispanic, Indian, Asian, and Black Ph.D. students, who by all accounts he treated with the same respect as anyone else.

I didn’t know Ed Wilson very well, but the handful of times we met and talked I recall being surprised at his gentle and kind demeanor and complete lack of any prejudice whatsoever toward any human groups, with the possible exception of political ideologues who verbally and physically assaulted him for suggesting a seemingly self-evident thing that nearly all scientists today accept as common knowledge, namely, that the human capacity for thought and behavior has a genetic component. The evidence is overwhelming that the charges against Wilson as a promoter of race science, or worse, as a racist, are false.

A final point that shouldn’t need to be said in a liberal enlightened society like ours, but evidently does need repeating: The presumption of innocence is a bedrock of Western jurisprudence, and it should be in the court of public opinion as well, which in today’s cancel culture has a propensity to reverse William Blackstone’s ratio and conclude that it is better that ten innocent persons suffer than that one guilty person escape. Given the social, economic, and personal consequences of being labeled a racist in today’s culture—an order of magnitude worse than that during the first sociobiology wars—evidence for the charge had better be far beyond a reasonable doubt. In the case of Ed Wilson, the evidence is nonexistent. To punctuate the point, I close this investigation with the full quote from Wilson that expands on the epigraph at the top of this article:

To keep the record straight, I am happy to point out that no justification for racism is to be found in the truly scientific study of the biological basis of social behavior. As I stated in On Human Nature, “I will go further and suggest that hope and pride and not despair are the ultimate legacy of genetic diversity, because we are a single species, not two or more, one great breeding system through which genes flow and mix in each generation. Because of that flux, mankind viewed over many generations shares a single human nature within which relatively minor hereditary influences recycle through ever changing patterns, between the sexes and across families and entire populations.”

If there is a possible hereditary tendency to acquire xenophobia and nationalist feelings, it is a non sequitur to interpret such a hypothesis as an argument in favour of racist ideology. It is more reasonable to assume that a knowledge of such a hereditary basis can lead to the circumvention of destructive behaviour such as racism, just as a knowledge of the hereditary basis of haemoglobin chemistry and insulin production can lead to the amelioration of their pathological variants.

These are hardly the views of a man with even a hint of racist propensities—adjacent, unconscious, systemic, implicit, or otherwise. In short, Edward O. Wilson was not a racist, nor a promoter of race science, and to suggest otherwise is a disservice to one of the great American scientists.

###

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University, the host of The Michael Shermer Show, and for 18 years a monthly columnist for Scientific American. He is the author of a number of New York Times bestselling books including Why People Believe Weird Things, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, Heavens on Earth, and Giving the Devil His Due. His next book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational, to be published Fall, 2022.

When I studied anthropology, around the year 2000, I quickly realized that the left-wing activists in the field viewed any biological/genetic explanation to human behavior as highly “problematic”. Any time someone suggested that there were genetic bases for behavior such as rape or male aggressiveness, for example, they would immediately stand accused of “excusing” and “normalizing” said behavior, mostly by people who held purely socioconstructivist approaches and who clearly did not grasp the science presented to them.

It's clearly become worse since with the “woke” movement. Now, the mere acknowledgement that humans are biological entities at all is tantamount to holding Nazi views. Witness how even sex is now viewed as having no basis in biology, but is purely explained as a social status “imposed at birth”… Basically, any time you refer to biology to explain anything, you will be called a sexist, a transphobe, a racist, etc., depending on what you’re trying to explain. Case closed!

My wife is a biochemist/neuroscientist. A few years ago, I remember explaining these debates to her. She would roll her eyes, sighing at how childish and unserious we were in the social sciences departments. I kept telling her to watch out, because when they were done imposing their ideology in my department, they would come for hers. This is what we’re witnessing today. And the most scary part is, science seems to be caving in.

When you make it impossible for anyone who wants a successful career in science to research racial differences between groups, what you also do is give racists a killer answer to the assertion that there is no evidence for such differences:

“Of course there isn’t - you’ve stopped anyone from looking for it” they say.

All the research that shows our species to be intellectually homogeneous, everything we have discovered about the role poor environment plays in the developments of IQ, all of it counts for nothing against the assertion that of course you’ll never find what you never look for. That argument is a powerful weapon, and we’re handing it over, fully loaded, to some extremely dangerous people.