Why I Am Not a Christian

A response to Ayaan Hirsi Ali's declaration "Why I am Now a Christian"

On November 11, 2023, my friend, colleague, and hero Ayaan Hirsi Ali released a statement explaining "Why I am Now a Christian".

I have known Ayaan for many years. She has been a guest on my podcast, and I on her podcast. We have appeared together at conferences. I have read all of her books and support her heroic work defending women’s rights, civil rights, free speech, and freedom of religious expression, along with her brave stand against intolerance, bigotry, and hate, religious or otherwise. I’ll never forget when she spoke at Occidental College when I was a professor there, when during the Q&A two Muslim women dressed in the hijab accused her of Islamophobia for unfairly characterizing Islam as a religion of violence. “Then why do I have to have to travel with armed guards to protect me from death threats I receive from members of my own religion of Islam?” she rejoined understatedly and with characteristic aplomb. Ayaan has pride of place in the pantheon of greats who have had the courage of their convictions to the point of putting their own lives on the line in the name of universal principles of justice and freedom.

Nothing Ayaan has written in her essay changes my evaluation of her as a heroic figure. I simply think she is mistaken. We all are about a great many things. Maybe I am wrong here and she is right. But I think reason and history prove otherwise. Let me explain in the spirit of respect for what is on the line here, starting with the subtitle of Ayaan’s essay: “Atheism can't equip us for civilisational war.” She’s right, but not in the way she thinks.

Atheism per se can’t equip anyone for anything because it is not a belief system or worldview. Atheism just designates a lack of belief in God. Full stop. It is a purely negative statement, an indicator that someone does not believe. A lack of belief can never be the basis of a belief system. I am an atheist in the same sense that I am an a-supernaturalist or an a-paranormalist. There is no such thing as the supernatural or the paranormal. These descriptors are just linguistic place-holders for mysteries we have yet to explain. Once explained, they move into the realm of the natural and the normal. If there is a realm of the supernatural or the paranormal, there is no way for a natural and normal being like us to perceive or understand it.

From this misunderstanding of what atheism is, Ayaan deduces that it can’t handle the stressors of current events:

Western civilisation is under threat from three different but related forces: the resurgence of great-power authoritarianism and expansionism in the forms of the Chinese Communist Party and Vladimir Putin’s Russia; the rise of global Islamism, which threatens to mobilise a vast population against the West; and the viral spread of woke ideology, which is eating into the moral fibre of the next generation.

Again, she’s right. Atheism can do nothing about these threats because it is not a positive assertion of principles that counter authoritarianism, expansionism, Islamism, China, Russia, and woke ideology. What can? Ayaan mentions “modern, secular tools: military, economic, diplomatic and technological efforts to defeat, bribe, persuade, appease or surveil.” She says these are not enough because “we find ourselves losing ground.” Are we? I don’t think so. But it’s a debatable point, so let’s set aside for a moment the matter of whether or not the world is getting better or worse this week, month, or year, and take the long view of what has driven moral progress over the centuries.

In my books The Moral Arc and Giving the Devil His Due I show that it isn’t atheism bending the arc of justice and freedom, but Enlightenment humanism—a cosmopolitan worldview that places supreme value on human and civil rights, individual autonomy and bodily integrity, free thought and free speech, the rule of law, and science and reason as the best tools for determining the truth about anything. It incorporates scientific naturalism, the principle that the methods of science operate under the presumption that the world and everything in it is the result of natural processes in a system of material causes and effects that does not allow, or need, the introduction of supernatural forces. By extension from above, if God is a supernatural being outside of space and time and therefore unknowable in any rational or empirical manner, it is not possible for natural creatures like us to understand a supernatural deity.

Scientific naturalism and Enlightenment humanism made the modern world, and many of the founding fathers of the United States, for example Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, Benjamin Franklin, James Madison, and John Adams, were either practicing scientists or were trained in the sciences, and their construction of the Constitution and the principles on which it is based were thoroughly secular and based on the best science and philosophy of the day. It is my hypothesis that in the same way that Galileo and Newton discovered physical laws and principles about the natural world that really are out there, so too did the founders discover moral laws and principles about human nature and society that really do exist.

Just as it was inevitable that the astronomer Johannes Kepler would discover that planets have elliptical orbits—given that he was making accurate astronomical measurements, and given that planets really do travel in elliptical orbits, he could hardly have discovered anything else—scientists studying political, economic, social, and moral subjects will discover certain things that are true in these fields of inquiry. For example, that democracies are better than autocracies, that market economies are superior to command economies, that torture and the death penalty do not curb crime, that burning women as witches is a fallacious idea, that women are not too weak and emotional to run companies or countries, that blacks do not like being enslaved, and that the Jews do not want to be exterminated. Why?

The answer is that it is in human nature to struggle to survive and flourish in the teeth of nature’s entropy, and having the freedom, autonomy, and prosperity available in free societies—built as they were on the foundation of scientific naturalism and Enlightenment humanism that seek to discover the best way for humans to live— enables individual sentient beings to live out their evolved destinies. This is moral realism, and it doesn’t require a deity to justify its validity. Steven Pinker explains the logic:

If I appeal to you to do anything that affects me—to get off my foot, or tell me the time or not run me over with your car—then I can’t do it in a way that privileges my interests over yours (say, retaining my right to run you over with my car) if I want you to take me seriously. Unless I am Galactic Overlord, I have to state my case in a way that would force me to treat you in kind. I can’t act as if my interests are special just because I’m me and you’re not, any more than I can persuade you that the spot I am standing on is a special place in the universe just because I happen to be standing on it.

This is the principle of the interchangeability of perspectives (developed in Pinker’s 2018 book Enlightenment Now), which is the core of the oldest moral principle discovered multiple times around the world throughout history: the Golden Rule. Pinker notes that it also forms the basis of “Spinoza’s Viewpoint of Eternity, the Social Contract of Hobbes, Rousseau and Locke; Kant’s Categorical Imperative; and Rawls’s Veil of Ignorance. It also underlies Peter Singer’s theory of the Expanding Circle—the optimistic proposal that our moral sense, though shaped by evolution to overvalue self, kin and clan, can propel us on a path of moral progress, as our reasoning forces us to generalize it to larger and larger circles of sentient beings.”

Thus, there are perfectly rational reasons to ground morals and values in universal humanistic principles, and these do not depend on adherents being theists or atheists. That they are universal principles mean that they apply to all people—Jews, Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, pantheists, deists, agnostics, and atheists. Whether or not there is a God—much less the Christian God—is irrelevant. That’s what universal means.

Are there good reasons to believe in God? Theists certainly think that there are, but atheists are just as certain that there are not. Who is right? I have written numerous articles, essays, reviews, and book chapters on this subject, and in my next book, Truth: What it is, How to Find it, Why it Matters (forthcoming from Johns Hopkins University Press in 2025) I review the top 20 philosophical and scientific arguments for God’s existence and the counterarguments against them, so I won’t adjudicate the matter here. I will simply note that both sides have strong arguments and that, ultimately, it is not a question that can be definitively answered in the affirmative through philosophy or science, so it comes down to faith—one either makes the leap for personal reasons, or not.

As for Christianity, since Ayaan has declared her fielty to that particular faith over all others, I will concede her point that on the three threats facing the West that concern her (and me)—(1) the authoritarianism/expansionism of Islamism, (2) China and Russia, and (3) woke ideology—Christian conservatives have a clearer vision than atheist (or even theist) Leftists about the threat that Islamism, China and Russia, and woke ideology pose to the West (including and especially the LGBTQ community that would not fare well under such regimes). But this is political pragmatism pure and simple—“Say what you want about Christian conservatives, at least they know what a woman is!” I’m sympathetic to the sentiment, but is it a basis for a worldview? I think not. We should believe things because they are true, not just because they are politically pragmatic.

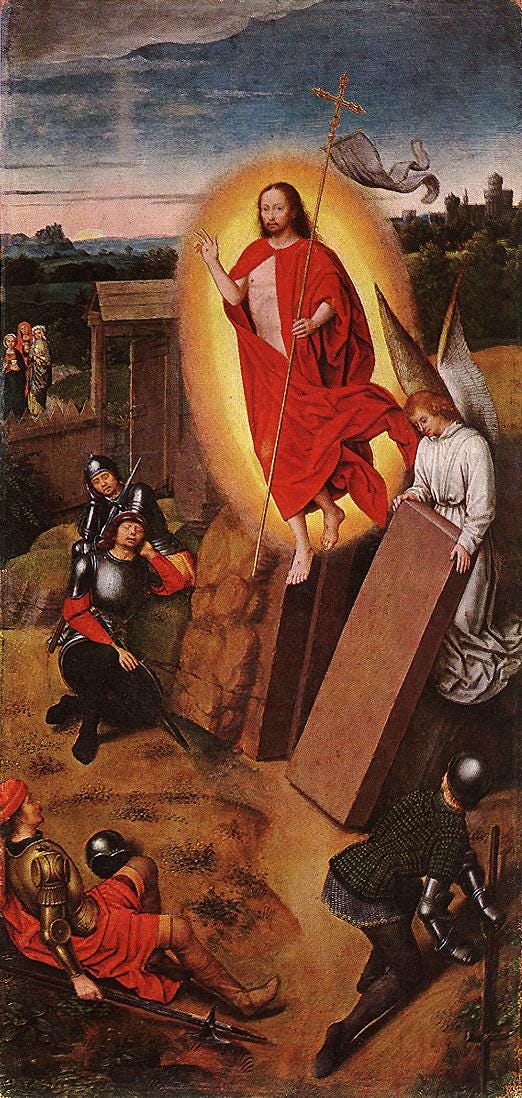

Consider what’s on demand in Christianity—that Jesus was the Messiah, was crucified, and was resurrected from the dead. (As the apostle Paul said in 1 Cor. 15:13-19: “if there is no resurrection of the dead, then Christ is not risen. … And if Christ is not risen, your faith is futile; you are still in your sins!”) Is that true? My first question is this: Why don’t Jews accept the resurrection as real, either in Jesus’ time or in ours? Jews believe in the same God as Christians. They accept the same holy book as Christians do (the Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament). They even believe in the Messiah. They just don’t think the carpenter from Galilee was him. Jewish rabbis, scholars, philosophers, and historians all know the arguments for the resurrection as well as Christian apologists and theologians, and still they reject them. That’s telling.

What would it take for a rational person to accept the resurrection? Let’s put some numbers on it. Demographers estimate that throughout all of human history approximately 100 billion people have lived before the 8 billion people alive today. Not one has died and returned from the dead, unless you are a Christian, in which case you believe that one person did—Jesus of Nazareth. So the claim that one person out of those 100 billion people who died came back from the dead would be extraordinary indeed—100 billion to 1. Is the evidence extraordinary for the resurrection? No. It’s not even ordinary.

According to the University of Wisconsin-Madison philosopher Larry Shapiro in his 2016 book The Miracle Myth, “evidence for the resurrection is nowhere near as complete or convincing as the evidence on which historians rely to justify belief in other historical events such as the destruction of Pompeii.” Because miracles are far less probable than ordinary historical occurrences like volcanic eruptions, “the evidence necessary to justify beliefs about them must be many times better than that which would justify our beliefs in run-of-the-mill historical events.” But, says Shapiro, it isn’t. In fact, it’s not even as good as ordinary historical events.

What about the eyewitnesses? Maybe, Shapiro suggests, they “were superstitious or credulous” and saw what they wanted to see. “Maybe they reported only feeling Jesus ‘in spirit,’ and over the decades their testimony was altered to suggest that they saw Jesus in the flesh. Maybe accounts of the resurrection never appeared in the original gospels and were added in later centuries. Any of these explanations for the gospel descriptions of Jesus’s resurrection are far more likely than the possibility that Jesus actually returned to life after being dead for three days.”

The principle of proportionally—or extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence—also means we should prefer the more probable explanation over the less, which these alternatives surely are. Therefore, I am not a Christian because there is not enough evidence to believe that the core doctrines about Jesus’s resurrection are true. And I don’t want to believe in things that have to be believed in to be true.

What about the moral and political principles of Christianity upon which the West is claimed to be based? In The Moral Arc I make the case that Christianity went through the Enlightenment and came out the other end with the values so revered today by Westerners. This was not due to some new revelation from God (“thou shalt grant women equal rights as men”, “thou shall not enslave thy fellow humans”) or interpretation of scripture (“Galatians 3:28, ‘There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus,’ is actually channeling the 1964 Civil Rights act that prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin.“) Rather, once moral progress in a particular area is underway due to secular forces, most religions eventually get on board—as in the abolition of slavery in the 19th century, civil rights and women’s rights in the 20th century, and gay rights in the 21st century—but this often happens after a shamefully protracted lag time.

The world’s religions are tribal and xenophobic by nature, serving to regulate moral rules within the community but not seeking to embrace humanity outside their circle—unless they have inculcated the secular values of the Enlightenment, which most Christians have. Religion, by definition, forms an identity of those like us, in sharp distinction from those not like us, those heathens, those unbelievers. Most religions were pulled into the modern Enlightenment with their fingernails dug into the past. Change in religious beliefs and practices, when it happens at all, is slow and cumbersome, and it is almost always in response to the church or its leaders facing outside political or cultural forces.

Even if our morality does not originate in the Bible, religious believers will often argue that Christianity gave Western civilization its most precious assets: art, architecture, literature, music, science, technology, capitalism, democracy, equal rights, and the rule of law. First, no one disputes the magnificence of countless works of art, architecture, literature, and music that were inspired by Christianity: the great cathedrals that make the spirit soar, the requiems that capture the heartache of loss, the psalms of joy that unite listeners, the paintings that dazzle with light and human emotion.

But artists who live in a Christian world, who are surrounded by other Christians, who understand next to nothing beyond Christianity, and who are likely being supported by Christian patrons, are going to produce Christian work. Christianity was the dominant religion at a moment in history when Europe was going through a Renaissance and an explosion of discoveries of new lands and new political and economic systems; no wonder it ended up being the great patron. The fact that artists living in Christendom were inspired by the life and death of Jesus by crucifixion, and not, say, by the life and death of the Buddha by mushrooms, is not a surprise. Christianity was the only game in town.

As for Christianity forming the basis of democracy and capitalism, we can run the historical counterfactual and make a prediction: if this hypothesis is true, then societies in which Christianity is or was the dominant religion should show Western-like forms of democracy and capitalism. They don’t. The Byzantine Empire, for example, was predominantly Eastern Orthodox Christian from the early A.D. 300s, and for seven centuries produced nothing remotely like democracy and capitalism as practiced in modern America. Even early America wasn’t like it is today when, a mere two centuries ago, women couldn’t vote, slavery was legal and widely practiced, and capitalism’s wealth was vouchsafed to only a tiny minority of land holders or factory owners. Throughout the late Middle Ages and well into the Early Modern Period, all the nation states, city states, and various political conglomerates of Western and Central Europe were not only Christian but Western Christian, and yet as late as the 19th century the only quasi-democratic republics in Europe were England, Holland, and Switzerland. In Christian Europe, both England and Spain profited handsomely from their overseas colonial empires, made more profitable yet by the decimation of the native populations and the looting of their troves of precious metals, gems, and other natural resources—actions that by today’s moral standards are condemned.

Finally, social scientist Gregory S. Paul conducted a correlational study of the societal health of 17 first-world prosperous democracies—Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Holland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United States—and religiosity (to what extent the citizens in each believe in God, are biblical literalists, attend religious services at least several times a month, pray at least several times a week, believe in an afterlife, and believe in heaven and hell, ranking them on a 1-10 scale). The results were striking…and disturbing. Far and away—without having a close second—the United States is not only the most religious of the 17 nations but also the most dysfunctional, scoring the worst on a wide range of 25 different indicators of social health and well being (on a 1-9 scale from dysfunction to healthy), including homicides, suicides, life expectancy, STDs, abortions, teen births, fertility, marriage, divorce, alcohol consumption, life satisfaction, corruption indices, adjusted per capita income, income inequality, poverty, employment levels, incarceration, and others.

Correlation is not causation, of course, and each of these measures has multiple causes having nothing to do with religion (or the lack thereof), but if religion is such a powerful force for societal health as Christian commentators claim, then why is America—the most religious nation in the Western world—also the unhealthiest on all of these social measures? If religion makes people more moral, then why is America seemingly so immoral in its lack of concern for its poorest, most troubled citizens, notably its children? While it would be too much to say “religion poisons everything,” as Christopher Hitchens famously concluded in his book God is Not Great, it is problematic enough to conclude that it is not needed to create a healthy society.

Atheism isn’t the alternative to the Judeo-Christian worldview, Enlightenment Humanism is. We can ground human morals and social values not just in philosophical principles such as Aristotle’s virtue ethics, Kant’s categorical imperative, Mill’s utilitarianism, or Rawls’ fairness ethics, but in science as well. From the Scientific Revolution through the Enlightenment, reason and science slowly but systematically replaced superstition, dogmatism, and religious authority. As the German philosopher Immanuel Kant proclaimed: Sapere Aude!—dare to know! “Have the courage to use your own understanding.” As he explained: “Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity.” The Age of Reason, then, was the age when humanity was born again, not from original sin, but from original ignorance and dependence on authority and superstition. Never again need we be the intellectual slaves of those who would bind our minds with the chains of dogma and authority. In its stead we use reason and science as the arbiters of truth and knowledge. As I said in my 2012 Reason Rally speech before a crowd of over 20,000 humanists and science enthusiasts on the mall in Washington DC:

Instead of divining truth through the authority of an ancient holy book or philosophical treatise, people began to explore the book of nature for themselves.

Instead of looking at illustrations in illuminated botanical books scholars went out into nature to see what was actually growing out of the ground.

Instead of relying on the woodcuts of dissected cadavers in old medical texts, physicians opened bodies themselves to see with their own eyes what was there.

Instead of human sacrifices to assuage the angry weather gods, naturalists made measurements of temperature, barometric pressure, and winds to create the meteorological sciences.

Instead of enslaving people because they were a lesser species, we expanded our knowledge to include all humans as members of the species through evolutionary sciences.

Instead of treating women as inferiors because a holy book says it is a man’s right to do so, we discovered natural rights that dictate that all people should be treated equally through the moral sciences.

Instead of the supernatural belief in the divine right of kings, people employed a natural belief in the legal right of democracy, and this gave us political progress.

Instead of a tiny handful of elites holding most of the political power by keeping their citizens illiterate and unenlightened, through science, literacy, and education people could see for themselves the power and corruption that held them down and began to throw off their chains of bondage and demand their natural rights.

The constitutions of nations ought to be grounded in the constitution of humanity, which science and reason are best equipped to understand. That is the heart and core of scientific naturalism and Enlightenment humanism.

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, Executive Director of the Skeptics Society, and the host of The Michael Shermer Show. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His new book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational.

I've seen this notion by various atheists including Shermer and Peter Boghossian that the Christian argument goes something like this:

1. I believe in the core tenets of Christianity but it's a faith-based decision, not based on rationality

2. Having lost point 1, I now turn to the practical benefits of Christianity

I think this is a misread, and because I believe that Shermer and Boghossian are both smart enough to know better, it comes off as intellectually dishonest. It's treating a "yes, and" argument as a "yes, but" argument, as though point 2 is meant to salvage the argument after point 1 has failed. That isn't what's going on in the mind of a Christian and they know that.

Fundamentally, Christianity a matter of faith, not rationality. Christians aren't hiding the ball here, they say it outright in the writings of Paul and other places. They say that there is no way to salvation but faith in Christ, and that this is a stumbling block to the Jews and foolishness to the Gentiles. When, thousands of years later, nonbelievers on Substack call it foolishness, that's not some new idea, but rather a very, very old one.

So we get the same dance every time. Shermer says that the only path to truth is rationality, and no other standard is valid. Christians say that God created a world that follows consistent natural laws, which is important, but that rationality isn't everything, and when it comes to what sort of person to be, they live by a different standard, faith. Shermer says, "aha, you cannot prove by rationality that your worldview is true!". Well, duh. In literally any situation where two groups are looking at an issue by different standards, they will come to different conclusions about who is right.

But then atheists will say, "but rationality is a better standard that faith". Sure, but that's a false binary. The difference between Christians and atheists isn't that one only accepts truth by faith and the other only accepts truth by evidence. Both do both, it's just that the latter category denies it.

Christians are perfectly comfortable using science as a tool to unravel truths about the natural world. I'm a Christian and a chemist. No problem. But then Shermer claims that atheism is completely a negative proposition, and that his decisions in life are rationally determined. Sure. I'm sure it's "the most advanced findings on the topic" that makes him love his family.

That really doesn't wash when you behold the complexity of existence, the limitations of our understanding, and the finite nature of existence on Earth. There are some things that science may never figure out. There are other things that science will not figure out in our lifetimes. For those things will we choose not to engage with them? In some cases it's impossible. Instead, we will rely on tradition, heuristics, or often just gut feelings, as Shermer and literally everyone else does on a daily basis.

Read more Nietzsche, Michael. The problem with your argument is that the enlightenment is the consequence of Christian values and aligned values from other religions. There can be no deriving morality without God. Nietzsche tried and knew the project could not succeed. Ayn Rand tried and failed. Marx and Marxists tried and failed. We have a choice between religions of God or religions that make a God out of a man, an idea, or a nation. There is a cosy humanist conceit that they can derive morality independently, when in fact these humanists are just echoing the Christian moral culture of their birth. With every generation distant from religion this birth-culture fades. Morality degenerates into the worship of self or the worship of power, or both. As Nietzsche saw, as Rand found out. If your intellect is superior to these two (to name but two), the burden of proof (not mere assertion) is on you.