Abortion: The Case for Choice, Part 2

Part 2 of a 3-Part series on continuous thinking, conflicting rights, bodily autonomy, potential life v. actual life, and how to reduce unwanted pregnancies

In part 1 of this 3-part series I argued that (1) the binary-thinking of the pro-life argument that human life and personhood begins at conception is a fallacy because the development of consciousness and personhood is a continuous process, (2) even if we agree that a fetus is a human being what we have then is a conflicting-rights issue between the rights of the mother and the rights of the fetus, so (3) if rights are to be legally protected for one over the other, a stronger case can be made for a woman than a fetus because, (4) an actual human being and rights-bearing person must take precedence over a potential human being and person, and (5) the fundamental right of bodily autonomy is one that has historically been expanding to include all adult humans including and especially women.

In part 2 of this series (below) I will show that left unprotected, rights-bearing groups tend to restrict the freedoms of those in non-rights-bearing groups, historically most notably of men over women. In part 3, I will seek common ground between pro-life and pro-choice advocates by focusing on how to reduce unwanted pregnancies.

Why Men Want to Control Women’s Reproductive Choices

In the conflicting-rights model I have employed here, another reason for supporting the rights of women over the rights of fetuses has to do with what has happened in the past when men lorded it over women, especially their reproductive choices. (I explored this history in detail in The Moral Arc, so here I will provide a truncated summary.) One reason for this domination is as obvious as it is simple: In general, and on average, men are bigger and stronger than women and they have used this biological fact—as they do when they can against other males in contests over hierarchy, territory, or mates—to their advantage in exerting dominance.

One arena in which this plays out is in regard to reproduction, where men and women differ in certainty about their offspring, a concept captured by the phrase “mother’s baby, father’s maybe.”1 Women know with 100 percent certainty that they are the mothers of their children, whereas men know with less than 100 percent certainty the paternity of their issue. Much follows from this phenomenon, starting with the reason for paternity uncertainty.

Researchers estimate that anywhere between 1 percent and 30 percent of babies are the product of an “extra-pair paternity” (EPP) in which the biological father is not the partner of the mother.2 The percentage varies so wildly because of cultural differences between populations studied, along with the error margins inherent in the difficulties in collecting data on such a sensitive subject (i.e., people are generally disinclined to disclose details of their private sex lives to curious social scientists).3 The anthropologist Brooke Scelza, for example, documented an EPP rate of 17 percent of all recorded marital births among the traditional society of the Himba in Northern Namibia, and that such EPPs were “associated with significant increases in women’s reproductive success.”4 The evolutionary biologist Maarten Larmuseau and his colleagues, however, found a much lower rate of 1-2 percent in a Western European population in Flanders, Belgium, noting that “This figure is substantially lower than the 8-30 percent per generation reported in some behavioural studies on historical EPP rates, but comparable with the rates reported by other genetic studies of contemporary Western European populations.”5

To better understand this widely varying data I consulted the evolutionary psychologist Martie Haselton, who told me she estimates that “the range of nonpaternity in the West is 2-4 percent and perhaps a bit higher elsewhere in the world.” She explained the wider range of figures in nonwestern countries this way: “In addition to the strength of norms about marriage, there are norms about fidelity that vary across populations. In the Himba women marry, but there seems to be an accepted norm that people will sleep around. So, women might not suffer the extreme costs that other women suffer if their infidelities are discovered. That might allow them to be freer to pursue a dual mating strategy.” A dual mating strategy is one in which women seek to secure a sound investment in parental care and resources through one partner and obtain good genes through another partner if both sets of characteristics are not present in one man. As Haselton explained the phenomenon:

In principle, women could benefit from both material and heritable benefits conferred by male partners, but both sets of features may be difficult to find in the same mate. Men who display indicators of good genes are highly attractive as sex partners; hence, they can, and often do, pursue a short-term mating strategy that tends to be associated with reduced investment in mates and offspring. Therefore, women may often be forced to make strategic trade-offs by selecting long-term social partners who are higher in investment attractiveness than sexual attractiveness.6

Haselton also cautioned that extrapolating from modern data to ancestral environments is problematic in that “another issue to consider is that the modern world affords women more independence and privacy. Ancestral women didn’t travel on business trips or have husbands who did so.”7

Warning against adultery, Crispijn van de Passe (II), Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1611 - 1639 (Photo by: Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Whatever the rate of EPPs was historically—most likely higher in the distant past compared to today in which the institution of monogamous marriage is energetically encouraged by both church and state—the point is that a woman could, theoretically, select a dual-mating strategy, and it is this possibility that leads men to try to control women’s reproductive choices. Even if no offspring result from an EPP sexual encounter, infidelity rates are high enough the emotion of jealousy evolved as a proxy for the phenomenon of mate guarding—fending off potential mate poachers and preventing mates from defecting to another partner.8

Apollo shoots the pregnant Coronis dead. The crow denouncing her adultery flies above the shooter. Apollo takes the child Asclepius from Coronis belly. To his left is the cremation of Coronis imagined, print maker: Hendrick Goltzius (workshop of), Date 1590 (Photo by: Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

How high are rates of infidelity in the modern world? Studies vary, but according to the National Opinion Research Center in Chicago, about 25 percent of American men and 15 percent of American women have had an affair at some point during their marriage.9 Other studies find a range of between 20 percent and 40 percent of heterosexual married men, and between 20 percent and 25 percent of heterosexual married women who have philandered while married (keeping in mind the usual caveats about such self-reporting data).10 As the evolutionary psychologist David Buss notes: “Those who failed in mate guarding risked suffering substantial reproductive costs ranging from genetic cuckoldry to reputational damage to the entire loss of a mate.” The result, he argues, is a range of mate guarding adaptations, from “vigilance to violence.”11

The threat of infidelity is real, as evidenced in a survey of single American men and women that found 60 percent of men and 53 percent of women admitted to “mate poaching,” or trying to entice or charm someone out of their current relationship in order to enter into one with them.12 An anthropological survey identified mate poaching as common in at least 53 other cultures.13

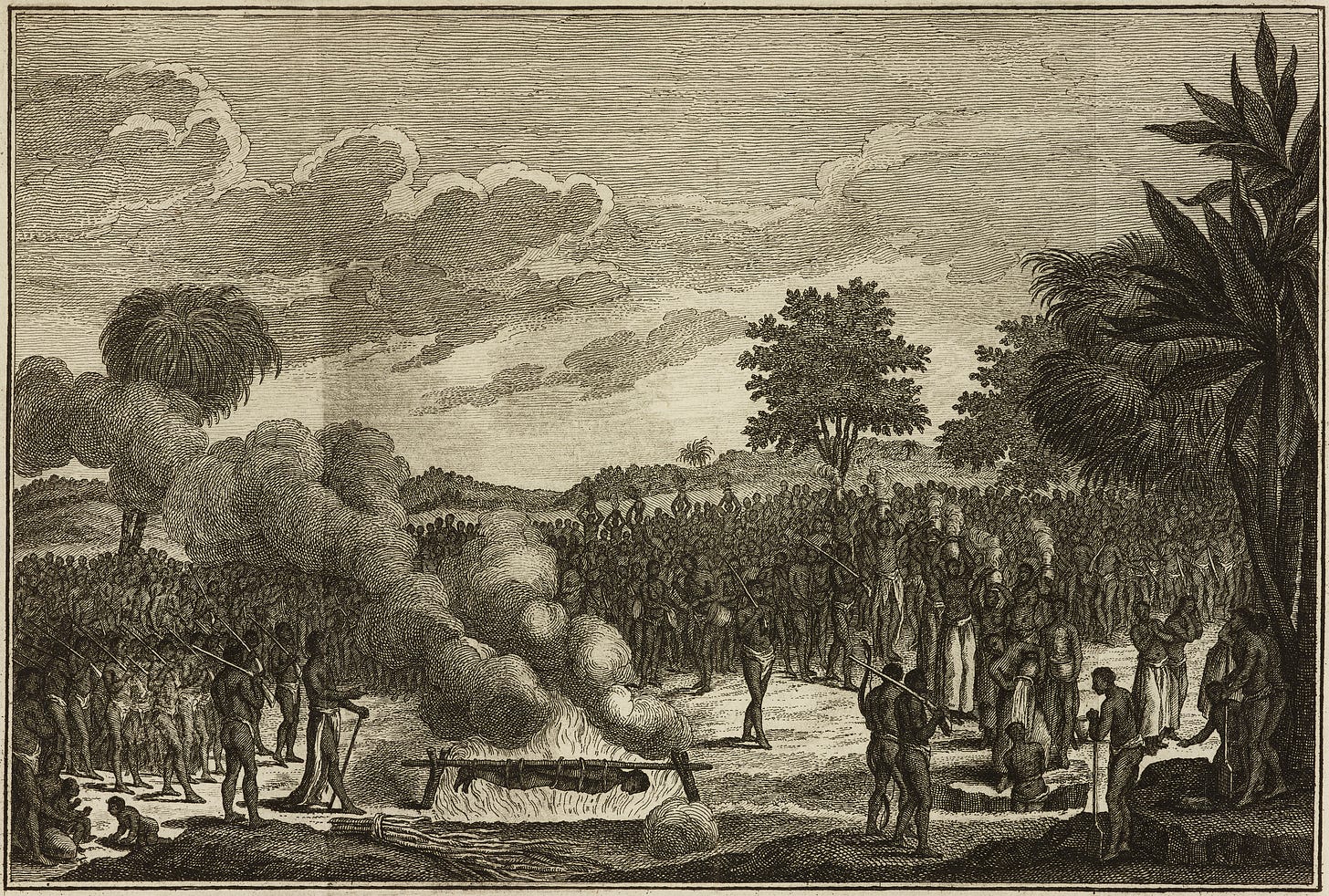

Woman burned alive, punishment for the adulterous wives of the king of Juida and their lovers, Benin, Africa, engraving from Compendio della storia generale de' viaggi (Summary of the general history of travel), volume 5, by Jean-Francois de La Harpe, 1781, Venice. (Photo by Icas94 / De Agostini Picture Library via Getty Images)

Although both men and women philander, get jealous, and mate guard, in the context of expanding women’s reproductive rights and men’s attempt to restrict them, male jealousy and mate guarding—whether through vigilance or violence—are strong causal factors. Studies show, for example, that in the U.S. more than twice as many women were shot and killed by their husband or intimate partner than were murdered by strangers using guns, knives, ropes, lead pipes, or candlestick holders.14 And women make up the majority of victims of intimate partner/family-related homicides.15

Caught in adultery, 16th century, digital improved reproduction from a publication from 1880. (Photo by: Bildagentur-online/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

From stalking to chastity belts to female genital mutilation, throughout history men have tried to control women’s sexuality and reproductive choices. And women have developed numerous strategies in response: clandestine affairs, mariticide (killing one’s husband), contraception, abortion, and infanticide.

Hardness of Life not Hardness of Heart: Infanticide and Abortion

Anthropologists and historians tell us that infanticide has been practiced by all cultures everywhere in the world throughout history, including and notably by adherents of all the world’s major religions. Historical rates of infanticide have ranged from 10 percent to 15 percent in some societies to 50 percent in others, but none lack it entirely.16

Bethlehemite Infanticide, oil on canvas, 65 x 79 cm, unmarked, Französischer Meister, 18. Jh., (?). (Photo by: Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Like all human behavior, infanticide has multiple causes, and the evolutionary psychologists Martin Daly and Margo Wilson unearthed some of the reasons in their study using an ethnographic database of 60 societies around the world. Of the 112 cases of infanticide in which anthropologists recorded a motive, 87 percent supported the “triage theory” of infanticide, which posits that mothers must make hard choices when times are hard (i.e., they kill their children when resources are too scarce to support another infant), a concept well captured in Edward Tylor’s 19th-century anthropological observation that “Infanticide arises from hardness of life rather than hardness of heart.”17

Nature is not infinite in its resources and not all organisms that are born can survive. When conditions are difficult parents, especially mothers, must decide who is most likely to survive—including future potential children who may fare better when conditions are improved—and sacrifice the rest. Daly and Wilson’s survey turned up these reasons for infanticide: disease, deformity, weakness, a twin when parents have only enough resources for one, an older sibling too close in age for resources to support both, hard economic times, no father to help raise the child, or because the infant was fathered by a different sexual partner.18

In Eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven, Uta Reinke-Hannemann notes how widely infanticide was practiced in ancient Greece and Rome, and the Catholic Church’s prohibition against it goes back to Middle Ages.19 During the historical period of the early rights revolutions, both church and state tried to do something to curb infant killings without addressing the underlying causes. Injunctions were approved and laws were passed, but just as in the bad old pre-Roe days of back alley abortions, if a woman didn’t want her baby, there was little anyone could do about it. Mothers would “accidentally” roll over on top of their infants during sleep (called “overlying”), or they dropped them off at foundling homes where the business of infant disposal was swift and private. Wet nurses and “baby farmers” were also tasked with the business of baby removal. In mid-19th-century London it was reported that public parks and other spaces were the site of as many dead babies as dead dogs and cats.

While it may seem unlikely that if Roe v. Wade is overturned and most states ban the practice that we will see the return of infanticide, given our history it is not impossible, so this too must be factored into the abortion debate, along with the more likely prospect of illegal abortions on a black market. And conservatives, of all people, should remember what happens when people want something and there is no free market exchange for it: black markets develop in response (prostitution and drugs being the most salient examples). Banning abortion will not end the practice. What will?

In Part 3 of this series I will suggest a solution that I hope both pro-life and pro-choice advocates can get behind: reducing unwanted pregnancies, which would reduce abortions, and that should be our joint goal. Instead of moralizing over the ultimately insoluble issue of whose side is right in a conflicting-rights issue like abortion, we should work toward the eminently soluble problem of unwanted pregnancies.

###

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University, the host of The Michael Shermer Show podcast, and the author of numerous New York Times bestselling books including: Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, Heavens on Earth, and Giving the Devil His Due. His next book is on conspiracy theories and why people believe them.

Buss, David. 2003. The Evolution of Desire: Strategies of Human Mating. New York: Basic Books, 266.

Hrdy, Sara. 2000. “The Optimal Number of Fathers: Evolution, Demography, and History in the Shaping of Female Mate Preference.” Annals of the New York Academy of Science 907, 75-96.

Goetz, Aaron T., Todd K. Shackelford, Steven M. Platek, Valerie G. Starratt, and William F. McKibbin. 2007. “Sperm Competition in Humans: Implications for Male Sexual Psychology, Physiology, Anatomy, and Behavior.” Annual Review of Sex Research, 18(1), 1-22.

Scelza, Brooke A. 2011. “Female Choice and Extra-Pair Paternity in a Traditional Human Population.” Biology Letters, December 23, Vol. 7, No. 6, 889-891.

Lamoreaux, M. H. D., J. Vanoverbeke, A. Van Geystelen, G. Defraene, N. Vanderheyden, K. Matthys, T. Wenseleers, and R. Decorte. 2013. “Low Historical Rates of Cuckoldry in a Western European Human Population Traced by Y-Chromosome and Genealogical Data.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B, December, Vol. 280, No. 1772.

Pillsworth, Elizabeth and Martie Haselton. 2006. “Male Sexual Attractiveness Predicts Differential Ovulatory Shifts in Female Extra-pair Attraction and Male Mate Retention.” Evolution and Human Behavior, 27, 247-258.

Personal correspondence, December 17, 2013.

Buss, David. 2001. The Dangerous Passion: Why Jealousy is as Necessary as Love and Sex. New York: Free Press.

Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. 1994. The Social Organization of Sexuality: Sexual Practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tafoya, M., A. & Spitzberg, B. H. 2007. “The Dark Side of Infidelity: Its Nature, Prevalence, and Communicative Functions.” In B. H. Spitzberg & W. R. Cupach (Eds.), The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication (2nd ed., 201-242). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Buss, David. 2002. “Human Mate Guarding.” NeuroEndocrinology Letters, December, 23(4), 23-29.

Schmitt, D. P., & Buss, David M. 2001. “Human Mate Poaching: Tactics and Temptations for Infiltrating Existing Mateships.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80:894-917.

Schmitt, DP, L Alcalay, J Allik, A Angleitner, L Ault, et al. 2004. “Patterns and Universals of Mate Poaching Across 53 Nations: The Effects of Sex, Culture, and Personality on Romantically Attracting Another Person’s Partner.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86:560-584.

Kellerman, A. L. and J. A. Mercy. 1992. “Men, Women, and Murder: Gender-Specific Differences in Rates of Fatal Violence and Victimization.” Journal of Trauma, July, 33(1), 1-5. https://bit.ly/31GiUFw

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2011. Global Study on Homicide: Trends, Contexts, Data. https://bit.ly/3dtPAES

Williamson, Laura. 1978. “Infanticide: An Anthropological Analysis.” In M. Kohl (Ed.) Infanticide and the Value of Life. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books.

Quoted in: Milner, Larry. 2000. Hardness of Heart, Hardness of Life: The Stain of Human Infanticide.” New York: University Press of America.

Daly, Martin and Margo Wilson. 1988. Homicide. New York: Aldine De Gruyter.

Ranke-Heineman, Uta. 1991. Eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven: Women, Sexuality and the Catholic Church. New York: Penguin.

GW1: Interesting article. I agree with a large part of it, but disagree with some points. I think it is important that skeptics, freethinkers, and atheists debate among themselves about important issues, like abortion, to see if we can reach some consensus.

MS1: ...(3) if rights are to be legally protected for one over the other, a stronger case can be made for a woman than a fetus because, (4) an actual human being and rights-bearing person must take precedence over a potential human being and person,...

GW1: A late-term fetus is a human being or human person, just as the pregnant woman. And a right to life should supercede a right to bodily autonomy. Without life, then no rights make any sense.

MS1: From stalking to chastity belts to female genital mutilation, throughout history men have tried to control women’s sexuality and reproductive choices.

GW1: And almost all of this control by men has been morally wrong. However, might there be cases when it is morally right? I think so.

MS1: While it may seem unlikely that if Roe v. Wade is overturned and most states ban the practice that we will see the return of infanticide, given our history it is not impossible, so this too must be factored into the abortion debate, along with the more likely prospect of illegal abortions on a black market.

GW1: I think that an increase in infanticide is extremely unlikely and that although illegal abortions are likely to increase, they are unlikely to be at the rate they were just prior to Roe v. Wade. Planned Parenthood and other similar organizations will help to transport women who want abortions to favorable states. This will become an efficient operation.

MS1: Banning abortion will not end the practice. What will?

GW1: Nothing will end the practice! In fact we should not want the end of abortion to ever happen. Why? Because there will ALWAYS be some unwanted pregnancies. We should always have safe, accessible, free, and legal abortions somewhere.

MS1: Instead of moralizing over the ultimately insoluble issue of whose side is right in a conflicting-rights issue like abortion, we should work toward the eminently soluble problem of unwanted pregnancies.

GW1: Although it is prudent to reduce unwanted pregnancies, and there are a variety of ways to do that, there are right sides in the conflict-of-rights’ situations involving abortion. Sometimes when there is a conflict in rights the mother is on the morally right side, sometimes the father is on the morally right side, and sometimes the fetal person is on the morally right side. I don’t think these conflicts are “ultimately insoluble.”