In an episode of the original Star Trek television series, entitled “Arena,” an alien species called the Gorn attacks and destroys the Earth outpost at Cestus III, leading Captain Kirk and the Enterprise to give chase in order to avenge this unprovoked and dastardly attack. Spock is not so sure about the alien’s motives, and wonders aloud about having “regard for another sentient being” but is interrupted by the more martial Kirk, who reminds him that, “out here we’re the only policemen around.”

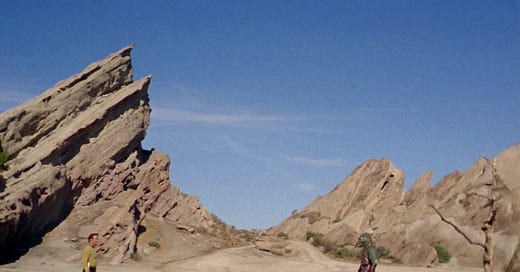

Their moral quandary is interrupted when both ships are stopped by an advanced civilization called the Metrons, who explain, “We have analyzed you and have learned that your violent tendencies are inherent. So be it. We will control them. We will resolve your conflict in the way most suited to your limited mentalities.” Kirk and the captain of the Gorn ship—a big-brained bipedal reptile—are transported to a neutral planet (that looks a lot like Vasquez Rocks on the outskirts of Los Angeles, the site of many SciFi and Western films) where they are instructed to fight to the death, at which point the loser’s ship and crew will be destroyed. The Gorn is stronger than Kirk and is easily able to rebuff his assaults that escalate from tree branch strikes to a massive boulder impact. He tells the Captain that if Kirk surrenders he will be “merciful and quick.”

“Like you were at Cestus III?”

“You were intruding! You established an outpost in our space.”

“You butchered helpless human beings.”

“We destroyed invaders, as I shall destroy you!”

Back on the ship where the crew is watching the battle unfold on the viewing screen, Dr. McCoy wonders aloud, “Can that be true? Was Cestus III an intrusion on their space?” “It may well be possible, Doctor,” Spock reflects. “We know very little about that section of the galaxy.” “Then we could be in the wrong,” McCoy admits. “The Gorn might have been simply trying to protect themselves.”

At the climax of the episode Kirk recalls the formula for making gunpowder after seeing the various elements readily available on the planet’s surface—sulfur, charcoal, and potassium nitrate, with diamonds as the deadly projectile—elements that the Metrons planted to see if judicious reason could triumph over brute strength.

Kirk puts them all together into a lethal weapon that he fires at the Gorn as the latter closes in for the kill. Now incapacitated, the Gorn drops his stone dagger, which Kirk grabs and places at the throat of his opponent in order to deliver the coup de grace. Then, at this moment of moral choice, Kirk opts for mercy. His reason drives him to take the moral perspective of his opponent. “No, I won’t kill you. Maybe you thought you were protecting yourself when you attacked the outpost.” Kirk tosses the dagger aside, at which point a Metron appears.

“You surprise me, Captain. By sparing your helpless enemy who surely would have destroyed you, you demonstrated the advanced trait of mercy, something we hardly expected. We feel that there may be hope for your kind. Therefore, you will not be destroyed. Perhaps in several thousand years, your people and mine shall meet to reach an agreement. You are still half savage, but there is hope.”1

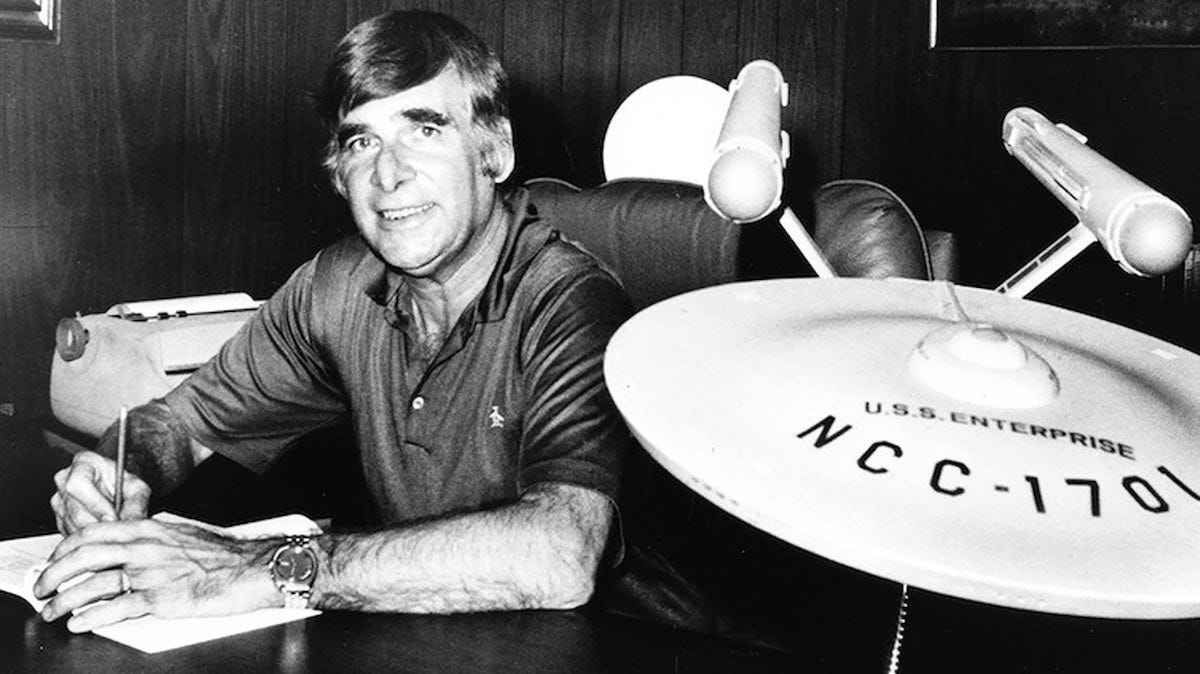

The creator of Star Trek, Gene Roddenberry, invented a genre unto itself with the creation of the magnificent Starship Enterprise, whose 23rd century mission was to expand humanity’s horizons, both physically and morally, via extraterrestrial interactions with the starship’s interracial, transnational, trans-species mixed crew. Each episode was both intrepid space adventure and thoughtful morality play, and many episodes explored the controversial issues of the age—and of all ages: war and conflict, imperialism and authoritarianism, duty and loyalty, racism and sexism, and how humanity might handle them centuries hence. Roddenberry made it clear that one of his goals with the series was to smuggle onto TV allegorical moral commentaries on current events. He said that by creating “a new world with new rules, I could make statements about sex, religion, Vietnam, politics, and intercontinental missiles. Indeed, we did make them on Star Trek: We were sending messages and fortunately they all got by the network.”2

Drama is one method, among many, of bringing about social change, and it is instructive to note that Roddenberry was personally well acquainted with war. In 1941, as a young man of 20, he’d enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps and flew 89 missions in the South Pacific, for which he was decorated with the Distinguished Flying Cross. So he knew of what he wrote when he opined:

The strength of a civilization is not measured by its ability to fight wars, but rather by its ability to prevent them.3

Hitting Back: The Evolutionary Logic of Aggression

Determining how to prevent wars very much depends on understanding the evolutionary origins and logic of aggression and violence. In my 2015 book, The Moral Arc, I worked this out, starting with a simple thought experiment.

If you were a molecule what would you do in order to survive? First you would need to build a substrate on which to generate a replication system inside of a cell that contains machinery for energy consumption, maintenance, and repair, and other features that keep the molecule intact long enough to reproduce. Once such molecular machinery is up and running the replicating molecules become immortal as long as there is energy to feed the system and an ecosystem in which these processes can take place. In time, these replicating molecules will out-survive non-replicating molecules by virtue of the very process of replication—those that don’t, die—thus the cells or bodies in which the replicators are housed are survival machines.

In modern jargon, the replicators are called genes and the survival machines are called organisms, and this little thought experiment is what Richard Dawkins means by the “selfish gene” in his book of that title.4 A cell, or body, or organism—a survival machine—is the gene’s way of surviving and perpetuating itself. Genes that code for proteins that build survival machines that live long enough for them to reproduce will win out over genes that do not. Genes that code for proteins and enzymes that protect its survival machine from assaults such as disease, help not just the organism to survive, but the genes as well. Survival, reproduction, flourishing: this is what survival machines do by their very nature. It is their—our—essence to strive to survive.

The problem is that survival machines scurrying around in, say, a liquid environment like an ocean or pond will bump into other survival machines, all of whom are competing for the same limited resources. “To a survival machine, another survival machine (which is not its own child or another close relative) is part of its environment, like a rock or a river or a lump of food,” says Dawkins. But there’s a difference between a survival machine and a rock. A survival machine “is inclined to hit back” if exploited. “This is because it too is a machine that holds its immortal genes in trust for the future, and it too will stop at nothing to preserve them.” Thus, Dawkins concludes, “Natural selection favors genes that control their survival machines in such a way that they make the best use of their environment. This includes making the best use of other survival machines, both of the same and of different species.”5

Survival machines could evolve to be completely selfish and self-centered, but there is something that keeps their pure selfishness in check, and that is the fact that other survival machines are inclined “to hit back” if attacked, to retaliate if exploited, or to attempt to use or abuse other survival machines in a preemptive first strike. So in addition to selfish emotions that drive survival machines to want to hoard all resources for themselves, they evolved two additional pathways to survival in interacting with other survival machines: kin altruism (“blood is thicker than water”) and reciprocal altruism (“I’ll scratch your back if you’ll scratch mine”).

By helping its genetically-related kin, and by extending a helping hand to those who will reciprocate its altruistic acts, a survival machine is helping itself. Thus, there was a selection for those who were inclined to be altruistic—to a point. With limited resources, a survival machine can’t afford to help all other survival machines, so it must assess whom to help, whom to exploit, and whom to leave alone. It’s a balancing act. If you’re too selfish, other survival machines will punish you; if you’re too selfless, other survival machines will exploit you. Thus, developing positive relationships—social bonds—with other survival machines is an adaptive strategy. If you are there to help your fellow group members when times are tough for them, they are more likely to be there when times are tough for you.

The Evolutionary Logic of Emotions

In this way survival machines develop networks and relationships that lead to interactions with one another that in addition to being neutral may be helpful or hurtful. From this we may derive the logic of moral emotions. In a social species such as ours, sometimes the most selfish thing you can do to help yourself is to help others, who will pay you back in kind, not necessarily out of some nebulous notion of “altruism” for its own sake, but because it pays to help others. But you can’t just fake being altruistic, as in the fullness of time others can detect your insincerity, so you must actually feel good about helping others, and here we hit bedrock of moral emotions. Our legacy is a moral emotion system that includes the capacity for us to help and hurt other survival machines, depending on what they do. Sometimes it pays to be selfish, but other times it pays to be selfless as long as you’re not a milquetoast who lies down and lets others run roughshod over your generosity.

The language I’m using to describe these interactions makes it sound like it is a rational process—a moral calculation conducted by survival machines as they interact with one another. But that is not what is going on. Organisms are driven by passions more than they are by reason. Natural selection has done the calculating for organisms, who evolved emotions as proxies for those calculations.

Emotions interact with our cognitive thought processes to guide our behaviors toward the goal of survival and reproduction. The neuroscientist Antonio Damasio has shown that at low levels of stimulation, emotions act in an advisory role, carrying additional information to the decision-making process along with input from higher-order cortical regions of the brain. At medium levels of stimulation, conflicts can arise between high-road reason centers and low-road emotion centers. At high levels of stimulation, low-road emotions can so overrun high-road cognitive processes that people can no longer reason their way to a decision and report feeling “out of control” or “acting against their own self-interest.”6

Conflicts among survival machines are an inevitable byproduct of the evolutionary logic of the essence to survive and flourish and the many different ways there are to fulfill that need in an environment of limited resources. This approach helps us see that there is a certain evolutionary logic to violence and aggression, a taxonomy of which Steven Pinker classified into five types in his book The Better Angels of Our Nature:7

(1) Predatory and Instrumental: violence as a means to an end, a way of getting something you want. Theft, for example, can grant the thief more resources necessary for survival and reproduction, and thus there evolved a capacity for cheating, stealing, and free riding (taking without giving in a social system) among some individuals in a group.

(2) Dominance and Honor: violence as a means of gaining status in a hierarchy, power over others, prestige in a group, or glory in sports, gangs, and war. Bullying, for example, can grant individuals higher status in the pecking order of social dominance.8 A reputation for being aggressive can be a credible deterrent against other aggressors. As the American singer-songwriterJim Croce explained the logic:

You don't tug on Superman's cape

You don't spit into the wind

You don't pull the mask off that old Lone Ranger

And you don't mess around with Jim

(3) Revenge and Self-Help Justice: violence as a means of punishment, retribution, and moralistic justice. Revenge, for example, is an evolved strategy for dealing with cheaters and free riders. Jealousy evolved to direct survival machines to mate guard against potential poachers of their sexual partner (and thus, for men, the bearer of their children who carry their genes), which when expressed violently can lead to spousal and intimate-partner violence and murder. Even infanticide has an evolutionary logic to it, as evidenced by the statistic that infants are 50 times more likely to be murdered by their stepfather than their natural father, an act far more common among species—including our own—than we care to admit.9

(4) Sadism: violence as a means of gaining pleasure at someone else’s suffering. Serial killers and rapists, for example, seem at least partially motived by the pain and suffering they cause, especially when it has no other apparent motive (such as instrumental, dominance, or revenge). It is not clear if sadism is adaptive or, more likely, is a byproduct of something else in the brain that evolved for some other reason.

(5) Ideology: violence as a means of attaining some political, social, or religious end that results in a utilitarian calculus whereby killing some for the sake of many is justified.

The Evolutionary Logic of Moral Emotions

Evidence that moral emotions are deeply entrenched in human nature may be found in a series of experiments with babies, succinctly synthesized in the psychologist Paul Bloom’s book Just Babies: The Origins of Good and Evil.10 Testing the theory that we have an innate moral sense as proposed by such Enlightenment thinkers as Adam Smith and Thomas Jefferson, Bloom provides experimental evidence that “our natural endowments” include: “a moral sense—some capacity to distinguish between kind and cruel actions; empathy and compassion—suffering at the pain of those around us and the wish to make this pain go away; a rudimentary sense of fairness—a tendency to favor equal divisions of resources; a rudimentary sense of justice—a desire to see good actions rewarded and bad actions punished.”11

Consider an experiment conducted in Bloom’s lab with a one-year-old baby who watched a puppet show in which one puppet rolls a ball to a second puppet, who passes the ball back to it. The first puppet then rolls the ball to a different puppet, who runs off with the ball. Next, the “nice” and the “naughty” puppets are placed before the baby, along with a treat in front of each; the baby is then given the choice of which puppet to take the treat away from. As Bloom predicted, the infant removed the treat from the naughty puppet—which is what most babies do in this experimental paradigm—but for this little moralist removing a positive reinforcement (the treat) was not enough. In his inchoate moral mind, punishment was called for, as Bloom recounts: “The boy then leaned over and smacked this puppet on the head.”12

Numerous permutations on this research paradigm (such as a puppet trying to roll a ball up a ramp, for which another puppet either helps or hinders it), show time and again that the moral sense of right (preferring helping puppets) and wrong (abjuring hurting puppets) emerges as early as 3-10 months of age—far too early to attribute to learning and culture.13 Young children who are exposed in a laboratory to an adult experiencing pain—the experimenter getting her finger caught in a clipboard say, or the child’s mother banging her knee—typically respond by soothing the injured party. Toddlers who see adults struggling to open a door because their arms are full, or to pick up an out-of-reach object, will spontaneously help without any prompting from the adults in question.14 Another experiment involved three-year old children who were asked, “Can you hand me the cup so that I can pour the water?” but the cup in question was broken. Remarkably, the youngsters spontaneously went in search of an intact cup to help the experimenter complete the task.15

Children are not always so beneficent, however, particularly with other children, with whom they clearly show awareness of an unequal distribution of rewards after a shared task (in this case a candy treat), but are not always so eager to unselfishly right the wrong by redistributing the wealth.16 But as children get older—from 3-4 year olds to 7-8 year olds—they are not only more aware of an unequal and unfair distribution of candy, they are more likely give away the extra unearned treat (50 percent of the 3-4 year olds did compared to 80 percent of the 7-8 year olds), showing that while the moral sense is inborn and instinctive, it is a capacity that can be tuned by learning and culture and brought to bear (or not) in different environments that either encourage or discourage helping or hurting behavior.17

As well, research with infants shows how early in life xenophobia takes root. Babies become wary of strangers, or anyone who doesn’t look like members of their family on whom they’ve imprinted, at a very early stage—days, in fact. In one experiment, three-day-old newborns were donned with headphones and special pacifiers that allowed them to pick audio tracks based on how rapidly they sucked on them. These infants not only figured out the connection between sucking and music selections, but they were able to transfer that learned skill to selecting a passage read to them from a Dr. Seuss book by their mother rather than a stranger. For newborns given the option to select among languages being spoken, results showed that “Russian babies prefer Russian, French babies prefer French, and American babies prefer English, and so on.” Even more remarkably, says Bloom, “This effect shows up mere minutes after birth, suggesting that babies were becoming familiar with those muffled sounds that they heard in the womb.”

Bloom’s conclusion about morality from this sizable body of research is instructive: “it entails certain feelings and motivations, such as a desire to help others in need, compassion for those in pain, anger towards the cruel, and guilt and pride about our own shameful and kind actions.”18 Of course society’s laws and customs can turn the moral dials up or down, but nature endowed us with the dials in the first place. It is as Voltaire said:

Man is born without principles, but with the faculty of receiving them. His natural disposition will incline him either to cruelty or kindness; his understanding will in time inform him that the square of twelve is a hundred and forty-four, and that he ought not to do to others what he would not that others should do to him.19

In my next column I will apply this evolutionary logic behind violence and agression to war, with an aim of understanding how to end it.

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, Executive Director of the Skeptics Society, and the host of The Michael Shermer Show. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His latest book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational. His next book is: Truth: What it is, How to Find it, Why it Matters, to be published in 2025.

References

“Arena” Star Trek. The Original Series. Season 1, Episode 19. January 19, 1967. Story by Fredric Brown. Teleplay by Gene L. Coon. Executive Producer Gene Roddenberry. The episode was film at Vasquez Rocks on the outskirts of Los Angeles, where so many SciFi films and shows are filmed. A transcript of this episode is available at: http://www.chakoteya.net/startrek/19.htm For a thoughtful discussion on the morality and ethics in Star Trek episodes see: Barad, Judity and Ed Robertson. 2001. The Ethics of Star Trek. New York Perennial Harper Collins.

Alexander, David. 1994. Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry. New York: Roc/Penguin.

The quote appears at the end of an episode entitled “Scorched Earth” of Gene Roddenberry’s television series Earth: Final Conflict.

Dawkins, Richard. 1976. The Selfish Gene. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ibid., 66.

Damasio, Antonio R. 1994. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: Putnam.

Pinker, Steven. 2011. The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, xxv, 508-509. Pinker notes that there are many taxonomies of violence citing, for example, the four-part scheme in: Baumeister, Roy. 1997. Evil: Inside Human Violence and Cruelty. New York: Holt.

Boehm, Christopher. 2012. Moral Origins: The Evolution of Virtue, Altruism, and Shame. New York: Basic Books.

Daly, Martin and Margo Wilson. 1999. The Truth About Cinderella: A Darwinian View of Parental Love. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Bloom, Paul. 2013. Just Babies: The Origins of Good and Evil. New York: Crown.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid., 7.

For a general review see: Tomasello, Michael. 2009. Why We Cooperate. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Warneken, F. and M. Tomasello. 2006. “Altrusitic Helping in Human Infants and Young Chimpanzees.” Science, 311, 1301-1303; Warneken, F. and M. Tomasello. 2007. “Helping and Cooperation at 14 Months of Age.” Infancy, 11, 271-294.

Martin, A. and K. R. Olson. 2013. “When Kids Know Better: Paternalistic Helping in 3-Year-Old Children.” Developmental Psychology, Nov., 49(11) 2071-2081.

LoBue, V., T. Nishida, C. Chiong, J. S. DeLoache, and J. Haidt. 2011. “When Getting Something Good is Bad: Even Three-Year-Olds React to Inequality.” Social Development. 20, 154-170.

Rochat, P., M. D. G. Dias, G. Liping, T. Broesch, C. Passos-Ferreira, A. Winning, and B. Berg. 2009. “Fairness in Distribution Justice in 3- and 5-Year-Olds Across Seven Cultures.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 40, 416-442; Fehr, E. H. Bernhard, and B. Rockenbach. 2008. “Egalitarianism in Young Children.” Nature, 454, 1079-1083.

Bloom, 2013, 31.

Voltaire. 1824. A Philosophical Dictionary, Vol. 2, London: John and H.L. Hunt, 258. http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/v/voltaire/dictionary/chapter130.html

Emotions set goals, rationality devises paths to achieve them. But emotions are not identical and uniform across species. The most noticable difference is between the sexes. Even a cursory aquaintence with adult males and females reveals that though they may be politically equal, they are certainly not alike. Most females are inherently drawn to infants and males turn all their activities into compititions -- who caught the biggest fish, bowled the highest score, etc. The young females obsession with looks and health compliments the young males obsession with risk as they prepare for the future they evolved to suceed in. In times of struggle, women will take their children and survive while the male will stand and fight and maybe die. He is the disposable half of the species.

You might like the sci-fi short story Arena on which the episode was based. No Gorn though.