“But I thought I had tenure!” RIP Frederick Crews, 1933-2024

The quintessential skeptic, Fred Crews was unrelenting in his pursuit of truth and fearless in his debunking of pseudoscience and pretentious nonsense

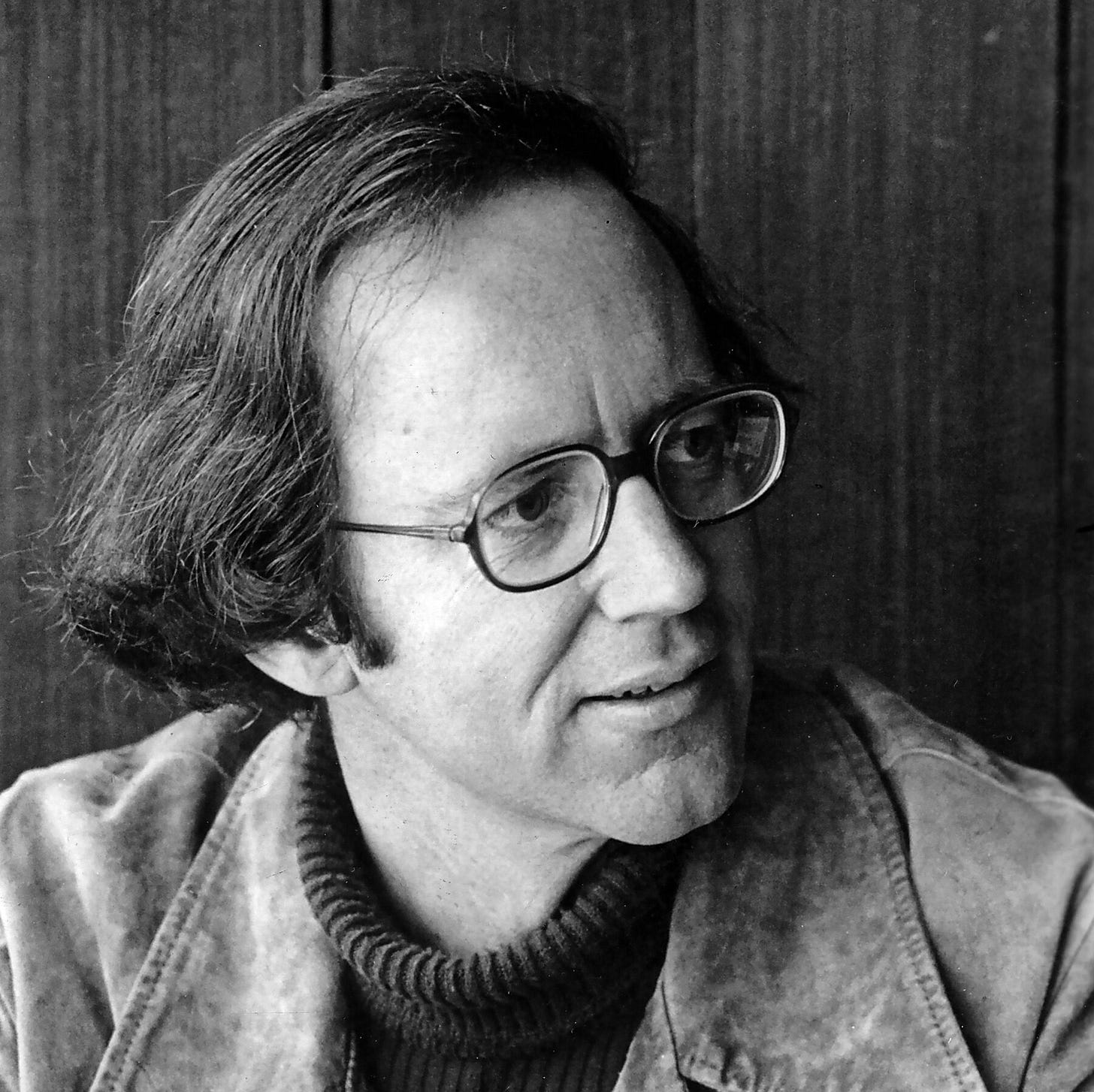

At Skeptic we were saddened to learn this week of the death of our long-time friend, contributor, and skeptical icon Frederick Crews, an admired professor of literature and the author of 14 books, many of which were widely read, discussed, and criticized for their satirical or argumentative import, and for their debunking of pretentious nonsense—from Freud, postmodernism, and repressed memories to creationism, theosophy, and UFOs. Fred died peacefully in the hospital at age 91 after a brief illness. His daughter, Gretchen Detre, provided details of her father’s life and career to us, along with these photographs, for which we are grateful. In addition to being a professor and public intellectual, Crews was a lifelong outdoorsman who ran in road races until age 72, remained a skier, swimmer, bodysurfer, and mountain hiker into his mid-80s, and rode his motorcycle until age 87, a true bon viviant.

Fred Crews was educated at Germantown Academy in Pennsylvania, where he was valedictorian and co-captain of the tennis team. At Yale, he won six academic prizes and graduated summa cum laude in 1955. His prizewinning senior thesis on Henry James was published as a book in 1957.

Crews acquired a Princeton Ph.D. in English in a record three years and then permanently moved to California, where he served on the UC Berkeley faculty from 1958 until his retirement, as chair of the English department, in 1994. In 1959 he married Elizabeth (Betty) Peterson, with whom he had two daughters and who became a successful photographer for child development textbooks.

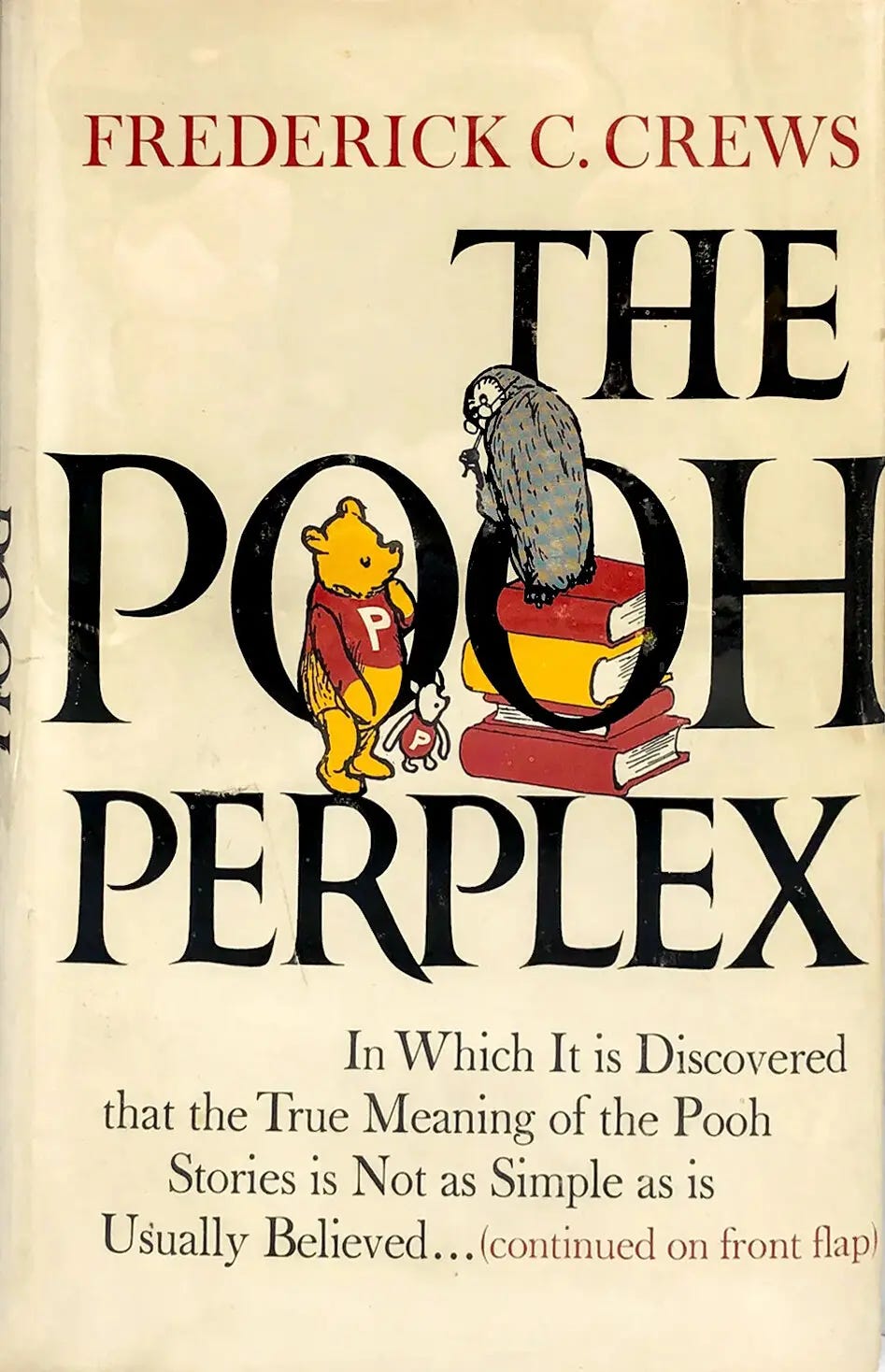

Crews began his academic career in a conventional way, publishing a monograph on the novelist E. M. Forster in 1962. In 1963, however, he surprised the world with a bestselling satire on literary criticism, The Pooh Perplex, which remains in print today.

Many years later, in 2001, it would find a successor in the mordant Postmodern Pooh. Both books employed parody to lampoon fashionable trends in academic discourse.

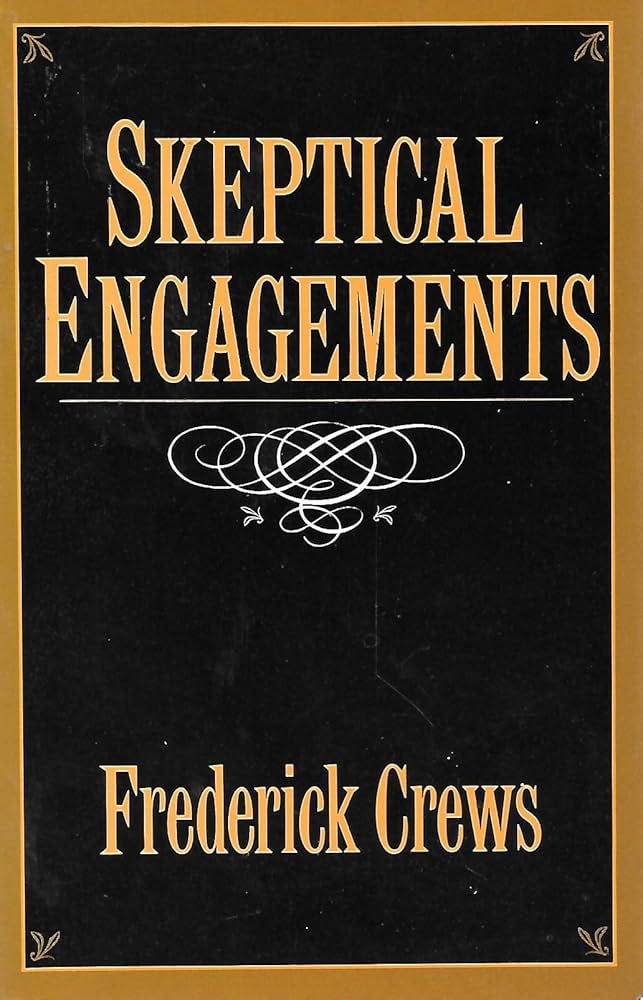

In the mid-1960s Crews became an outspoken activist against the Vietnam war, and his intellectual interests centered on Freudian psychoanalysis, which he adapted to literary explanation in an influential study of Nathaniel Hawthorne in 1966. Soon, however, Crews developed doubts about the cogency of Freudian doctrine, and in 1980 he began to publish critiques of what he now regarded as a pseudoscience. One result was Skeptical Engagements (1986), and another was a 1993 article in The New York Review of Books entitled “The Unknown Freud.”

That piece, and a later denunciation of “recovered memory” psychotherapy, elicited more controversy than any others in the history of the New York Review of Books. The whole affair, with protesting letters and Crews’s ripostes, became The Memory Wars (1995).

In 2017 Crews published a lengthy biographical study Freud: The Making of an Illusion, the aim of which was to trace the steps by which the founder of psychoanalysis gradually abandoned the empirical ethos. Writing in The New Yorker, Louis Menand characterized the book as having driven a stake “into its subject’s cold, cold heart.”

Historian of science and Freud scholar Frank Sulloway (Freud: Biologist of the Mind), a colleague of Crews at UC Berkeley, sent us this assessment of his work and influence:

What most impressed me about Fred Crews was the degree to which he systematically retooled himself by reading and carefully studying the modern scientific literature in neurology and psychology that had increasingly upended Freud’s most fundamental psychoanalytic assumptions. The same level of dedication was also true of Crews’s immersion in the history of science, which, beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, provided a critical reassessment not only of the intellectual sources of Freud’s thinking, but, more importantly, a far deeper understanding of the many fundamentally flawed biological theories that Freud carried over into his psychoanalytic model of human development.

Crews not only drew very effectively on this prior literature, but he also did the whole field of scholarship a considerable service by reprinting some of the most important publications from this literature in his 1998 edited volume Unauthorized Freud: Doubters Confront a Legend (Viking).

As Crews fully understood, a prime example of Freud’s mistaken application of biological theory to the human mind was his endorsement of the “biogenetic law,” a post-Darwinian theory that is most closely associated with German biologist Ernst Haeckel and that is known, more popularly, as ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny (individual development repeats the evolution of the species and all of its remote ancestors). For Freud, this supposed law of evolution provided a fundamental biological rational for his theory of psychosexual development—that children pass through the same three evolutionary stages of sexuality (oral, anal, and phallic) that can be found in our most distant ancestors, and that memories of such experiences can be inherited and then reexperienced by a child.

As Crews has noted, when Joseph Wortis, among others, confronted Freud in 1934 with the fact that any assumption that human memories can be inherited from one’s ancestors depends on Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s rejected belief in the inheritance of acquired characteristics, Freud responded bluntly, “But we can’t bother with the biologists. We have our own science.”

In addition, and throughout his writing and his scholarship, Crews had a way of leaving no stone unturned in the way he sifted through the prior literature on Freud and then reformulated its central ideas and findings in what was almost always a much more forceful and entertaining manner than before. His gift for critical literary expression, especially for zeroing in on the intellectual jugular vein of his victim (Freud), had an often devastating effect, while at the same time bringing new meaning and import to the previous scholarship on which he so effectively drew.

Crews’s other works include The Critics Bear It Away: American Fiction and the Academy (1992), which won a PEN award, and Follies of the Wise: Dissenting Essays (2006), endorsed by the renowned social psychologist Carol Tavris, who sent us this remembrance of her colleague:

Fred Crews was the consummate skeptic: deeply informed, fearless in calling bullshit, tireless in pursuit of justice and reason, always laced with humor and charm. Except, perhaps, when he was going after his Freudian adversaries, when his anger at the aforesaid bullshit occasionally got the better of him. (Actually, that passionate anger was the better of him.) In praising his book Follies of the Wise, I wrote, “Forget intelligent design. We need intelligent dissent.” That is Fred’s glowing legacy—illuminating in his words and actions the importance of dissenting from beliefs decades past their shelf life, especially those that fuel hysteria and cruelty. Whether exposing the flaws of an entire philosophy (Freudianism) and the “follies” of its practitioners or defending one lone soul railroaded into prison on waves of righteous hysteria (Jerry Sandusky), Fred was always steadfast, calm, and determined to speak truth as he saw it—truth to power, truth to ignorance, truth to cowardice. And what a gorgeous writer, equally skilled with the deft jab as with the prolonged argument! The forces of skepticism have lost a great warrior and I have lost a beloved friend.

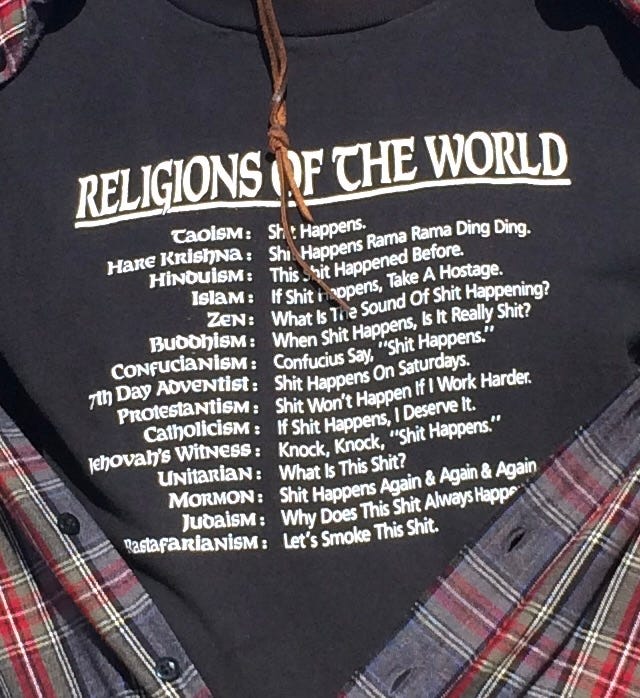

At Berkeley, Crews won a Distinguished Teaching Award, a Faculty Research Lectureship, and the Berkeley Citation, and he was named a Berkeley Fellow. He was also a Fulbright Scholar, received a Guggenheim fellowship, and was elected to membership in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was also an activist for skepticism and atheism, as evidenced in his proudly worn assessment of the world’s religions…

Late in his career Crews investigated the conviction of Jerry Sandusky, which he grew skeptical of the deeper he dug into the case. In 2018 Skeptic published a review by Crews of the science writer and journalist Mark Pendergrast’s 391-page book The Most Hated Man in America: Jerry Sandusky and the Rush to Judgment. (Pendergrast wrote two previous books on the debunked notion of “recovered memories”, which were invoked in the Sandusky trial: Victims of Memory: Sex Abuse Accusations and Shattered Lives and Memory Warp: How the Myth of Repressed Memory Arose and Refuses to Die.) Crews’s review essay for Skeptic, “Trial by Therapy: The Jerry Sandusky Case Revisited,” is long but well worth reading, as his agile mind grinds through the mountain of evidence presented in the trial and shows that there was “reasonable doubt” in the charges against him. Here is Fred’s summary:

Many factors contributed to the Sandusky debacle: a prurient misconstruction of well-meant deeds; excessive zeal by officials, police, social workers, and therapists; scandal mongering by the media that preempted the judicial process; the greed of abuse claimants and their lawyers; and a political vendetta against Penn State’s President Spanier by then Governor Tom Corbett. But the main ingredient in the witches’ brew, the one that rendered it most toxic, was something else: bogus psychological theory.

The indefinite and unsupported concepts of dissociation and repression, wielded without allowance for the distorting effects of suggestion and autosuggestion, lent forensic weight to nightmarish scenes that were “retrieved” in a climate of fright. Without that bad science, imparted first by therapy (Fisher) and then by social contagion (McQueary), there would have been no case at all against Sandusky. Attorney General Linda Kelly acknowledged as much in her triumphant press conference following the conviction. She praised the accusers for their courage and persistence in struggling toward a negation of their original statements to authorities. “It was incredibly difficult,” she proclaimed, “for some of them to unearth long-buried memories of the shocking abuse they suffered at the hands of this defendant.”

As Fred also noted, victims of abuse in everything from wars and genocides to domestic abuse and police violence do not have to “unearth long-buried memories” because said memories were never repressed in the first place, which is why PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) is a viable diagnosis and a serious problem. (Editor’s note: Even if one accept’s Crews’s assessment of the evidence presented in the trial, we cannot conclude that Sandusky was “innocent”; only that there is a “reasonable doubt” of his guilt.)

Fred Crews was a national treasure who will be dearly missed in the skeptical community and the wider society. He is survived by Elizabeth (Betty) Crews, his wife of almost 65 years; his children Gretchen Detre and Ingrid Crews; his grandchildren, Alejandro and Rebeca Márquez and Isabel and Aaron Detre; his great-granddaughter Yael Medrano Márquez; his sister, Frances James; and his nieces, Sigrid Bonner, Helen James, and Avis James.

Long ago, Fred Crews chose the sardonic text for his tombstone: “But I thought I had tenure!” We chose that for the title of this tribute. RIP Fred Crews.

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, Executive Director of the Skeptics Society, and the host of The Michael Shermer Show. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His latest book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational. His next book is: Truth: What it is, How to Find it, Why it Matters, to be published in 2025.

Thank you for this warm and fascinating remembrance of your friend. You’ve made me want to seek out some of Fred’s books and learn more.

> “But I thought I had tenure!”

👍🙂 Destined to be a classic right up there with "On the whole (in it?), I'd rather be in Philadelphia."

But some solid book recommendations -- bookmarked.