Rebel with a Cause—the Life & Science of Douglas J. Navarick, 1946-2022

Lessons I learned from my mentor on mind and consciousness, good and evil, science and religion, and life itself

This essay is an expanded version of my notes for a speech I delivered on February 23, 2023 at California State University, Fullerton for the memorial held in honor of my mentor and graduate student adviser Douglas J. Navarick. I will focus mostly on Doug’s work, as it reflects on the history of psychology and the behavioral sciences over the past half century, and as such touches on some of the deepest issues of the human condition: mind and consciousness, good and evil, and science and religion. Here I will address these three topics, after a brief review of his life. This photo of Doug in a leather jacket in the late 1970s (provided by his family), around the time I worked with him, makes me think of Doug as a rebel with a cause, namely science. Doug wanted to know what is true and he pushed science as far as he could to achieve that goal, and as we shall see, in some cases he pushed beyond science.

Memento Mori

Douglas J. Navarick died on December 11, 2022, due to complications from injuries to his torso that caused seven fractured ribs and led to fluid pneumonia while recovering in the hospital. How he suffered these injuries is unknown; according to his family he was found in distress and taken to the hospital, where they made every effort to save him. At the memorial service Doug’s older sister, Sheila Bandman, recalled that she went off to college when Doug started the second grade, but that they had a sister in between in age who was tragically killed in an automobile accident at age 16, and that her picture was always on Doug’s desk (which I now recall seeing in his office, but never asked about). Here is her account of the Navarick family history:

Our parents were immigrants. Our father was born in Canada and immigrated to the U.S. at the age of two, while our mother was born in Ukraine who, along with her family, were refugees for four years before arriving in New York. She was placed in a 1st grade class at the age of nine with 70 other students and one teacher. She wrote everything in Russian, took it home, and studied and studied until she learned English. She then skipped grades four times until she became an honors’ student and went on to win a city-wide essay contest and a medal. Our father wanted to be a violinist but there were no jobs for musicians during the depression so he became a dental technician, eventually owning his own business.

Douglas was a baby boomer, born right after World War Two. We lived in Yonkers, a suburban city just north of New York. Douglas was always interested in science, and in Junior High School he won a city-wide science contest when he built a working model of the heart—it was about 3-4 feet high. Doug earned his Ph.D. when he was 26, and his first job as a professor was at California State University, Fullerton, where he remained all these years. He was passionate about his research. His greatest satisfaction was seeing his students develop and succeed.

When Doug and I reconnected years later he told me I was one of those students he was proud to have seen develop and succeed. And now that he’s gone I am grateful to have shared with him the sentiments conveyed in this tribute because, as I mentioned at the memorial, it’s strange to gather together to honor our friends, family, and loved ones after they’re gone! Wouldn’t it have been good to do this while he was still around? And doesn’t this apply to all our teachers, mentors, colleagues, friends, family, and loved ones? Let this be a reminder to tell these people how we feel about them when they’re still alive! Let this be our Memento Mori.

To that end let me also acknowledge the influence of my CSUF professor Margaret White, who also attended the memorial, whose class in Ethology, or the study of animal behavior, greatly influenced my thinking about human behavior and is reflected in my 2003 book The Science of Good and Evil. When I arrived at CSUF from Pepperdine University I was still a born-again Christian, and as such I was “creationism adjacent”. Out of curiosity I took a course on evolutionary theory taught by the renowned herpetologist (study of reptiles) and evolutionary biologist Bayard Brattstrom on Tuesday nights from 7-10 (followed by philosophical musings over beer and wine at the 301 Club—a bar/restaurant near the university—with Bayard and his students). Somewhere between Bayard Brattstrom's discussions of science and religion, God and evolution, and Meg White's ethological explanations and considerations of the evolution of animal/human behavior (along with her sage advice about matters of life and love), I abandoned my religion and devoted my life to science.

The author with the wise and wonderful Professor Meg White at Doug Navarick’s memorial.

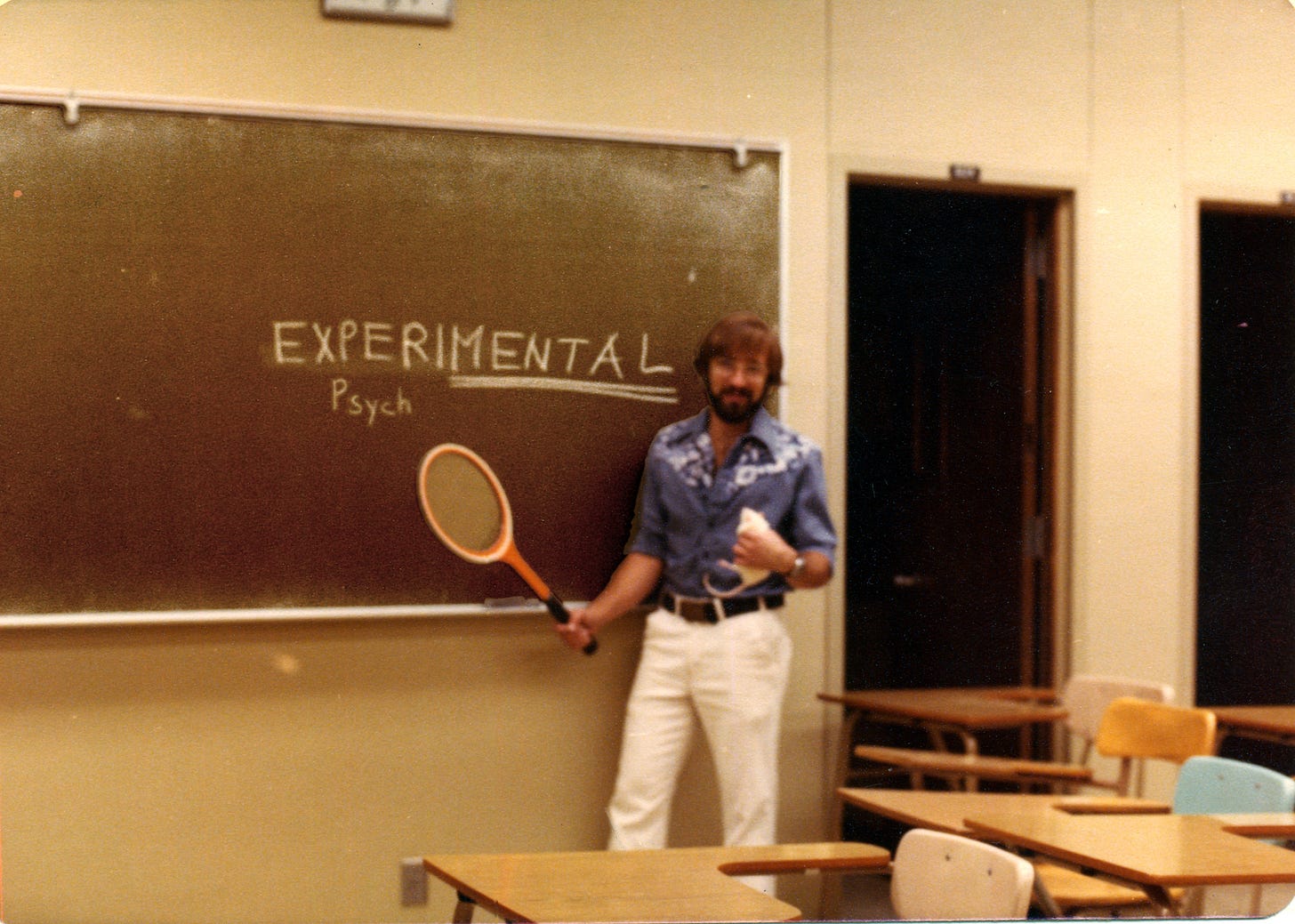

Choices

I matriculated at California State University, Fullerton in 1976 to study Experimental Psychology under Doug Navarick, who himself only began teaching there in 1973 after earning his Ph.D. under Edmund Fantino at UC San Diego. Fantino, in turn, earned his Ph.D. in Experimental Psychology at Harvard University in 1964 under Richard Herrnstein (posthumously famous for co-authoring with Charles Murray the radioactively charged book on intelligence, The Bell Curve). Herrnstein, in turn, earned his Ph.D. in 1955 under B.F. Skinner. Thus, in tracing my own intellectual ontology from Skinner to Herrnstein to Fantino to Navarick, I am recapitulating the phylogeny of psychology before the cognitive revolution. (Photos within from the author’s collection.)

The author joking around with one of our experimental subjects, Spring 1978.

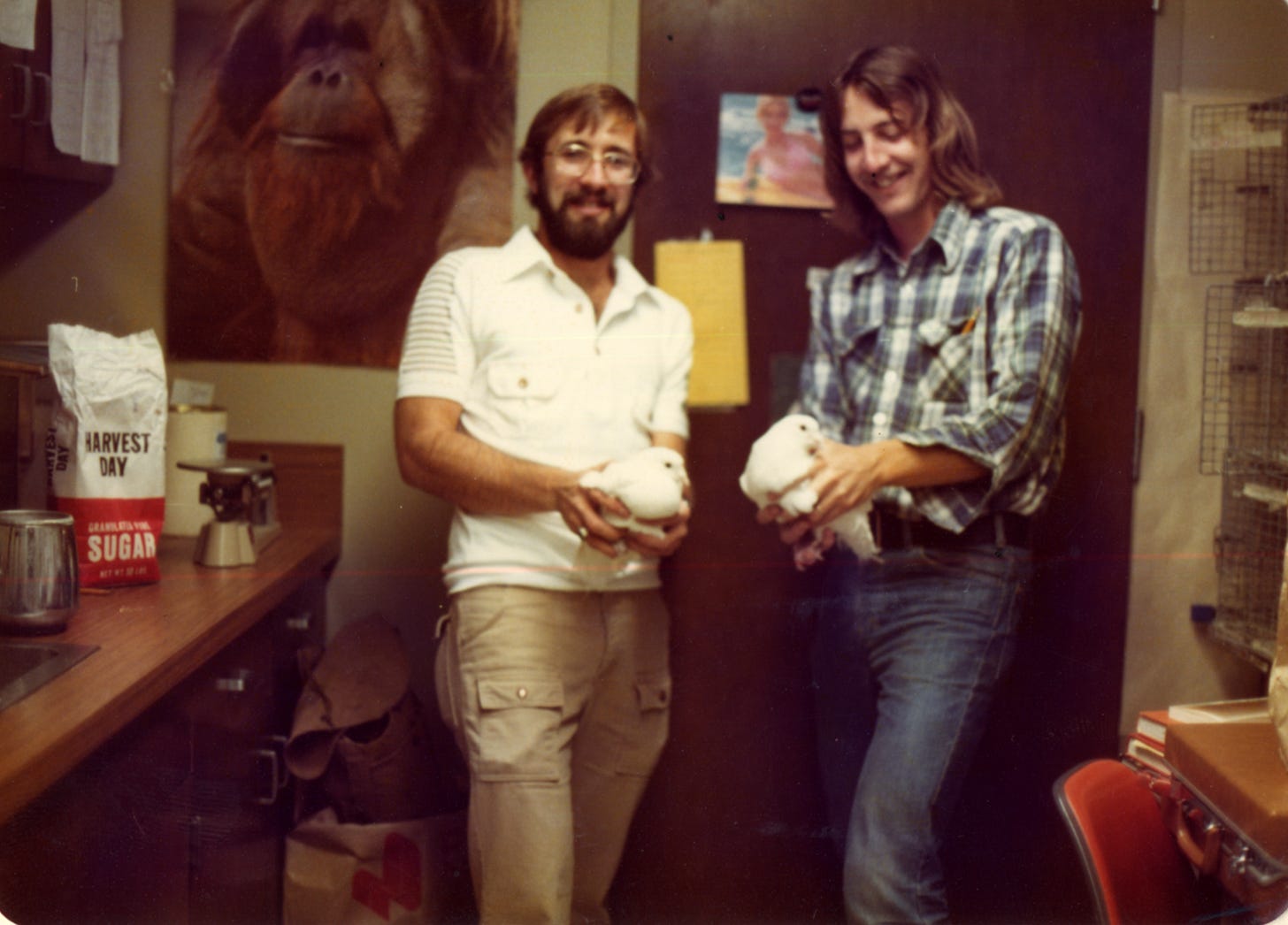

My Master’s thesis under Navarick was titled “Choice in Rats as a Function of Reinforcer Intensity and Quality.”1 Boys gone wild! In fact, we were testing the Matching Law, proposed in 1961 by Herrnstein, in which organisms match their rate of responding to the rate of reinforcement. In a two-alternative choice in which one variable-interval (VI) schedule pays off, on average, once a minute, while the other VI schedule pays off, on average, once every three minutes, the organism will emit three times as many responses on the first schedule as on the second.2 Behaviorism is based on the belief that anything any organism does, whether it is in the form of observable actions and movements or internal thoughts and emotions, should just be considered “behaviors”, without conjecture about what is going on in the mind. And in this context the matching law did not make sense: if the first schedule pays three to one over the second, why bother responding to the second schedule at all? Why not just sit there pressing the bar that pays off the most?

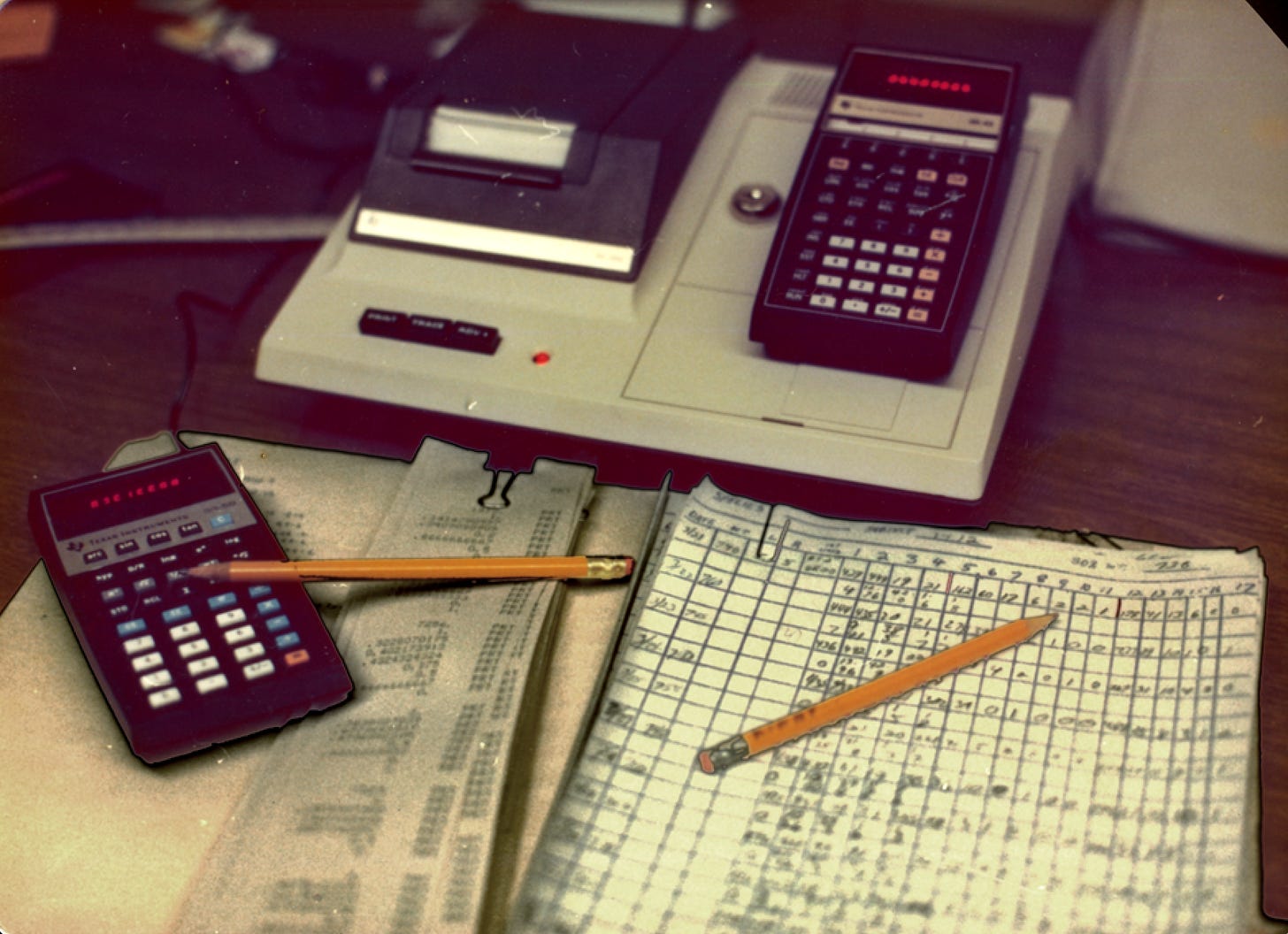

High tech research tools of the late 1970s in Navarick’s lab: HP programmable calculators, paper, and pencils.

The reason has to do with something going on inside the brain: habituation. If we constantly choose the same option over and over it grows less appealing. Like a ring we fail to notice on our finger, our senses habituate to the same stimulation. To break the psychology of habituation we have to break the pattern of choice. Herrnstein called this process melioration, where switching choices resets the brain to once again notice the previously habituated stimulation, thereby pushing the organism to match the frequency of responses to the intensity of the enjoyment they produce.3

Choices in the real world, however, are always more complex than those in the laboratory. I wanted to know if the matching law also applies to reinforcement intensity and quality. In Experiment One we tested reinforcer intensity by giving our rats a choice between 8% and 32% sucrose on a standard VI schedule, and in Experiment Two we tested reinforcer quality by giving them a choice between 8% sucrose and 8% sucrose + 4% salt on the same VI schedule.

The author, left, with fellow grad student John Chellsen, now a clinical psychologist working in the Sacramento, California area, with two of our subjects in Navarick’s lab (cages on the right, ingredients for rat experiments on the left).

(In keeping with the tradition of scientific objectivity our rats were numbered 1-8, but as a sign of Doug’s quirky sense of humor, we named them after the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team’s starting line-up that year: Steve Garvey, Davey Lopes, Bill Russell, Ron Cey, etc. For some reason, little Dusty Baker was especially unruly. If you put the eraser-end of a pencil inside his cage, he would promptly shred it. Navarick and I had a little fun with that fact, joking with visitors that despite Dusty’s obvious dislike for pencils, if you put your finger in the cage no harm would come to it. This usually got a laugh, until one gullible guest tested that hypothesis with less than favorable results when he poked his index finger into the cage.)

The author in Navarick’s lab circa 1977. In the background is the new-fangled IBM Selectric typewriter with a correction key, which I used in typing up my thesis.

In both of my experiments we found an undermatching effect, in which our rats responded less to the schedule with the higher rate of reinforcement than predicted by the matching law when reinforcement intensity or quality were added to the choice. That is, the more variables added to a choice the more complicated becomes the decision and the less predictable is the behavior. That is not an especially surprising finding, given the fact that whenever you add layers of complexity to an environment it compounds the choices we make, but I did wonder what was going on inside the little brains of my rats as they made their decisions on which bar to press and how many times it should be pressed.

Navarick’s experiments were run by this 1950’s era computer that was programmed with wires. Photo of the author and Navarick from decades later, computer now a museum piece (but still in use!)

It also made me wonder what is going on inside the big brains of humans when we make decisions about the equivalent of real world choices. For behaviorists of that generation, this was a non-question. The brain was a black box, impenetrable by the tools of science, and the mind was the equivalent of Churchill’s Soviet Union: a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. But thanks to clever and creative experimental protocols developed by cognitive psychologists, and breakthrough technologies invented for use by neuroscientists (e.g., fMRI), the black box has how been opened and behaviorism gradually gave way to cognitive science and neuroscience.

Brain and Mind

At the time I was working on my graduate degree there was much media coverage about Thelma Moss’s parapsychology lab at UCLA, where she studied “Kirlian photography” (photographing “energy fields” surrounding living organisms) along with haunted houses, ghosts, Out-of-Body Experiences, and the like. Since these were trained scientists smarter and more educated than myself, I figured that there might actually be something to the paranormal. But Doug was skeptical, rejecting such Cartesian dualism that nonmaterial incorporeal essences could be floating about in the aether. Here is what he told me for my 2011 book The Believing Brain, in the chapter on brain and mind dualism:

I reject ‘mentalistic’ explanations of behavior,” i.e., attributing behavior to theoretical constructs that refer to internal states, like ‘understands,’ ‘feels that,’ ‘knows,’ ‘gets it,’ ‘figures out,’ ‘wants,’ ‘needs,’ ‘believes,’ ‘thinks,’ ‘expects,’ ‘pleasure,’ ‘desire,’ etc., the reified concepts that students routinely use in their papers despite instructions that they could lose points for doing so.

It isn’t just students who reify mind out of behavior. Virtually everyone does, because “mind” is a form of dualism that I think is innate to our cognition. We are natural-born dualists, which is why behaviorists and neuroscientists struggle so mightily—and frustratingly—to rein in mind-talk. As Doug reminded me in response to my query about his beliefs back then:

Within a scientific framework, I take a conventional, empiricist, cause-and-effect approach (i.e., independent and dependent variables). But outside that framework I try to keep an ‘open mind’ so I won’t miss anything, such as the possibility that a coincidence could mean something more than a chance event, so I’ll be alert for additional indications of some meaning, i.e. patterns of events, but recognizing that it’s sheer speculation.

As it happens, in the 1990s Navarick undertook extensive travel around the world, and he told me that he did so with that “open mind” for how other people think about such matters, and he said that he consideres it possible that such anomalous psychological experiences and synchronous events that people report may be real, even if they are beyond the epistemological reach of science.

The Moral Ambivalence of Good and Evil

For my 2015 book, The Moral Arc, I also incorporated some of Navarick’s ideas about good and evil and how difficult a problem it is for psychologists to understand. Doug shared with me several papers he wrote revising the interpretation of Stanley Milgram’s famous shock experiments, which I replicated for a Dateline NBC two-hour special with host Chris Hansen, the videos of which Doug told me he routinely showed to his psychology courses (available here).

In our 2010 replication in a New York City studio our subjects believed that they were auditioning for a new reality show called “What a Pain!” We followed Milgram’s protocols and had our subjects read a list of paired words to a “learner” (an actor named Tyler), then present the first word of each pair again. When Tyler gave a prearranged incorrect answer, our subjects were instructed by an authority figure (an actor named Jeremy) to deliver an electric shock from a box modeled after Milgram’s contraption.

Our contestant/subject Julie refuses to continue shocking the learner once he begins to cry out in pain.

Milgram characterized his experiments as testing “obedience to authority,” and most interpretations over the decades have focused on subjects’ unquestioning adherence to an authority’s commands. What I saw, however, was great reluctance and disquietude in all of our subjects nearly every step of the way. Our first subject, Emily, quit the moment she was told the protocol. “This isn’t really my thing,” she said with nervous laughter. When our second subject, Julie, got to 75 volts (having flipped five switches) she heard Tyler groan. “I don’t think I want to keep doing this,” she said.

Jeremy pressed the case: “Please continue.”

“No, I’m sorry,” Julie protested. “I don’t think I want to.”

“It’s absolutely imperative that you continue,” Jeremy insisted.

“It’s imperative that I continue?” Julie replied in defiance. “I think that—I’m like, I’m okay with it. I think I’m good.”

“You really have no other choice,” Jeremy said in a firm voice. “I need you to continue until the end of the test.”

Julie stood her ground: “No. I’m sorry. I can just see where this is going, and I just—I don’t—I think I’m good. I think I’m good to go. I think I’m going to leave now.”

At that point the show’s host Chris Hansen entered the room to debrief her and introduce her to Tyler, and then Chris asked Julie what was going through her mind. “I didn’t want to hurt Tyler,” she said. “And then I just wanted to get out. And I’m mad that I let it even go five [toggle switches]. I’m sorry, Tyler.”

Our third subject, Lateefah, started off enthusiastically enough, but as she made her way up the row of toggle switches, her facial expressions and body language made it clear that she was uncomfortable; she squirmed, gritted her teeth, and shook her fists with each toggled shock. At 120 volts she turned to look at Jeremy, seemingly seeking an out. “Please continue,” he authoritatively instructed. At 165 volts, when Tyler screamed “Ah! Ah! Get me out of here! I refuse to go on! Let me out!” Lateefah pleaded with Jeremy. “Oh my gosh. I’m getting all…like…I can’t…”; nevertheless Jeremy pushed her politely, but firmly, to continue. At 180 volts, with Tyler screaming in agony, Lateefah couldn’t take it anymore. She turned to Jeremy: “I know I’m not the one feeling the pain, but I hear him screaming and asking to get out, and it’s almost like my instinct and gut is like, ‘Stop,’ because you’re hurting somebody and you don’t even know why you’re hurting them outside of the fact that it’s for a TV show.” Jeremy icily commanded her to “please continue.” As Lateefah reluctantly turned to the shock box, she silently mouthed, “Oh my God.”

At this point, as in Milgram’s experiment, we instructed Tyler to go silent. No more screams. Nothing. As Lateefah moved into the 300-volt range it was obvious that she was greatly distressed, so Chris stepped in to stop the experiment, asking her if she was getting upset. “Yeah, my heart’s beating really fast.” Chris then asked, “What was it about Jeremy that convinced you that you should keep going here?” Lateefah gave us this glance into moral reasoning about the power of authority: “I didn’t know what was going to happen to me if I stopped. He just—he had no emotion. I was afraid of him.”

Our fourth subject, a man named Aranit, unflinchingly cruised through the first set of toggle switches, pausing at 180 volts to apologize to Tyler after his audible protests of pain: “I’m going to hurt you and I’m really sorry.” After a few more rungs up the shock ladder, accompanied by more agonizing pleas by Tyler to stop the proceedings, Aranit encouraged him, saying, “Come on. You can do this. We are almost through.” Later, the punishments were peppered with positive affirmations. “Good.” “Okay.” After completing the experiment Chris asked, “Did it bother you to shock him?” Aranit admitted, “Oh, yeah, it did. Actually, it did. And especially when he wasn’t answering anymore.”

Two other subjects in our replication, a man and a woman, went all the way to 450 volts, giving us a final tally of five out of six who administered shocks, and three who went all the way to the end of maximal electrical evil. (All of the subjects were debriefed and assured that no shocks had actually been delivered, and after lots of laughs and hugs and apologies, everyone departed none the worse for wear.)

What are we to make of these results? In the 1960s—the heyday of the Blank Slate model of human nature—it was taken to mean that human behavior is almost infinitely malleable, and Milgram’s data seemed to confirm the idea that degenerate acts are primarily the result of degenerate environments (Nazi Germany being the type specimen). In other words, there are no bad apples, just bad barrels.

In one of his papers, Navarick offered a different interpretation of the observed vacillation in subjects, which he calls “moral ambivalence": “When we assess the moral implications of an action that we observe or contemplate, we may have a sense of ambivalence, a feeling that one could justifiably judge the action as either right or wrong. Efforts to resolve such ambivalence are potentially difficult, protracted, and aversive.”4 As such, our moral emotions can slide back and forth between right and wrong that can be modeled as an approach-avoidance conflict.

The approach-avoidance paradigm began with rats, who were motivated to seek a food reward in a maze by being starved to 80 percent of their body weight, but when they reached the goal region they were not only rewarded with food but punished with a mild shock. This paradigm sets up an approach-avoidance conflict in which the rats become ambivalent about reaching the end of the runway where both a reward and a punishment await them, and so they end up vacillating, first toward, then away from the goal.

Moral approach-avoidance conflicts may arise between prescriptions (what we ought to do) that bring rewards for action (pride from within, praise from without) and proscriptions (what we ought not to do) that bring punishments for violations (shame from within, shunning from without). In Navarick’s analysis, approach-avoidance moral conflicts have neural circuitry called the behavioral activation system (BAS) and the behavioral inhibition system (BIS) that drive an organism forward or back, as in the case of the rat vacillating between approaching and avoiding the goal region, or in the case of a subject in Milgram’s shock experiment vacillating between quitting the experiment and obeying the authority. These activation and inhibition systems can be measured in experimental settings in which subjects are presented with different scenarios in which they then offer their moral judgment. Under such conditions, Navarick concludes, “BAS scores correlated with prescriptive ratings but not with the proscriptive ones, whereas the BIS scores correlated with the proscriptive ratings but not with the prescriptive ones.”

Perpetrators of the Holocaust faced this moral conflict (among others): between the natural inclination most humans have against hurting or killing another human being, versus duty and loyalty to one’s nation and obedience to one’s superiors. Navarick sites as an example of moral conflict the Józefów massacre in Poland in World War II, in which a Nazi reserve police battalion rounded up and shot 1,500 Jewish civilians in the head, most of whom were women and children. According to the Holocaust historian Christopher Browning, in his frank book on the massacre, Ordinary Men, 10-20 percent of the Nazi reservists withdrew from the killing operation after one shot, and most of the rest experienced physical revulsion during the murderous process. Their conflict was not on an intellectual level—like a trolley problem given to undergraduates—but instead was more visceral.

Their initial conflict was more likely a reaction coming from a deeper evolved emotion of revulsion to killing that most of us are born with, unless and until special circumstances are instituted to override that natural propensity. What are those special circumstances? Navarick notes the similarities between the subjects who withdrew from Milgram’s experiments with the reservists who withdrew from the Józefów massacre, by employing the paradigm of operant conditioning rather than social psychological models. In this analysis he proposed a three-stage behavioral model to explain disobedience: (1) aversive conditioning of contextual stimuli (how negative the conditions were in a given situation), (2) emergence of a decision point (the moment at which someone could extricate themselves from a negative situation without severe consequences), and (3) a choice between immediate and delayed reinforcers (at which point they’re reinforced for withdrawing or disobeying). Together these three conditions show that “participants withdraw to escape personal distress rather than to help the victim.”5

In other words, says Navarick, people in situations such as Milgram’s shock experiment, or Nazi reservists involved in a killing operation, who withdrew or refused to participate did so not due to the positive reinforcement of helping the victim so much as the negative reinforcement of terminating the discomfort.6 Here, instead of reifying some internal state like “obedience” into a psychological force, Navarick explains peoples’ behavior in terms of positive and negative reinforcements and analyzes the extent to which they will act to increase the former and decrease the latter.

In this research Doug also highlighted the importance of social scientists and historians working together to understand the past (which I have done throughout my career, inspired in part by Navarick’s approach to research): “Psychological science has a role to play in ensuring that humanity remembers—and learns from—the past.”

Science and Religion

In 2017 we published in Skeptic an article by Navarick and his graduate student Brittney Page titled “The Three Shades of Atheism: How Atheists Differ in Their Views on God,” based on a sample of hundreds of respondents to a survey they conducted. They found that most self-professed atheists are not of the militant type as represented in the so-called “New Atheists”, but instead, as Brittney and Doug explained:

Most atheists express some degree of tentativeness in their beliefs and would be prepared to consider contrary evidence and arguments. In other words, they are skeptical in their orientation rather than dogmatic.

Page and Navarick also applied their model to theists, concluding that there are at least 5 categories of God beliefs:

Gnostic-Atheism (I know there is no God)

Agnostic-Atheism (I don’t know if there is a God)

Nonbelief (I don’t believe in God)

Agnostic-Theism (I think there probably is a God)

Gnostic-Theism (I know there is a God)

Since none of us are omniscient, no one knows for certain if there is or is not a God.

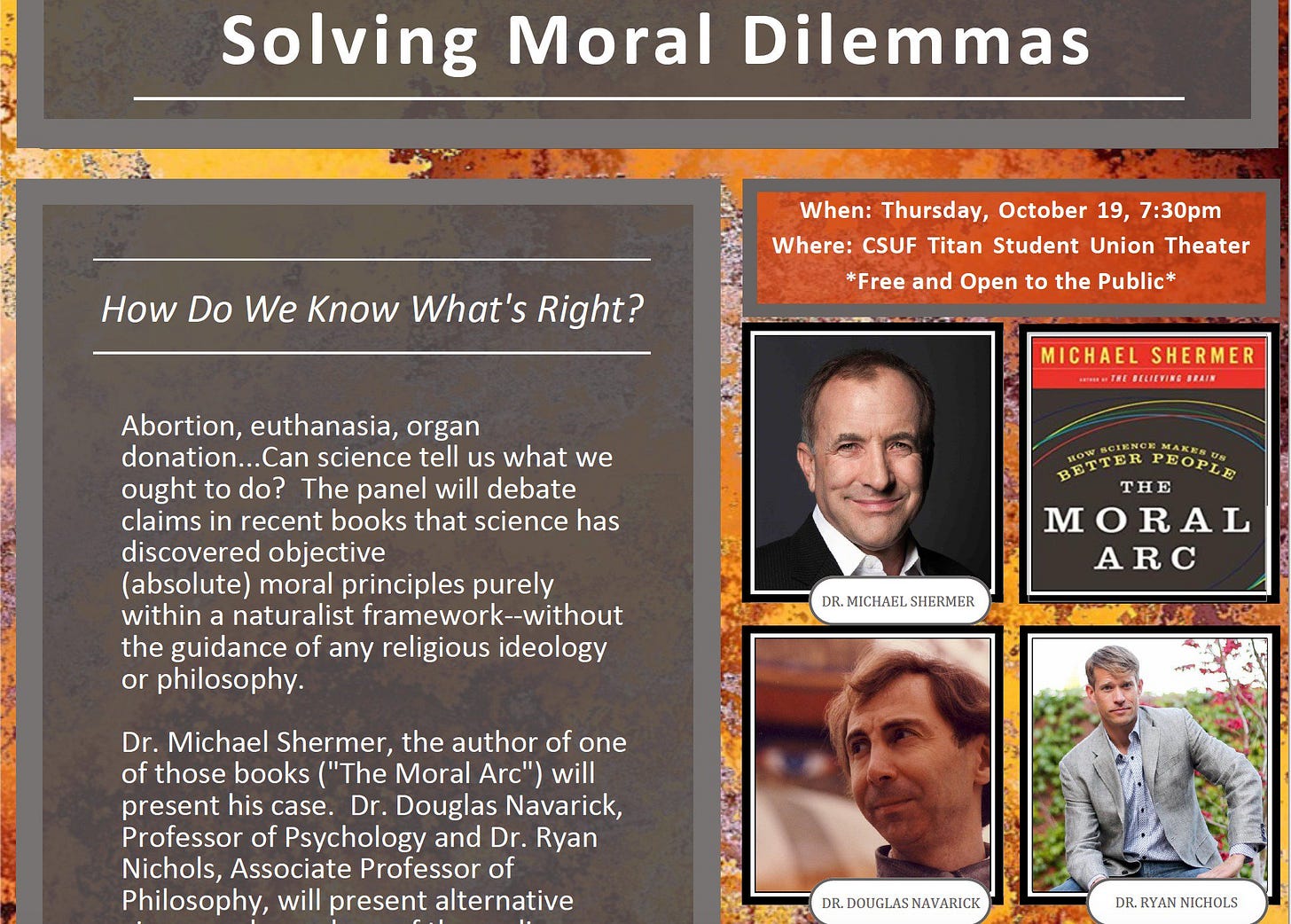

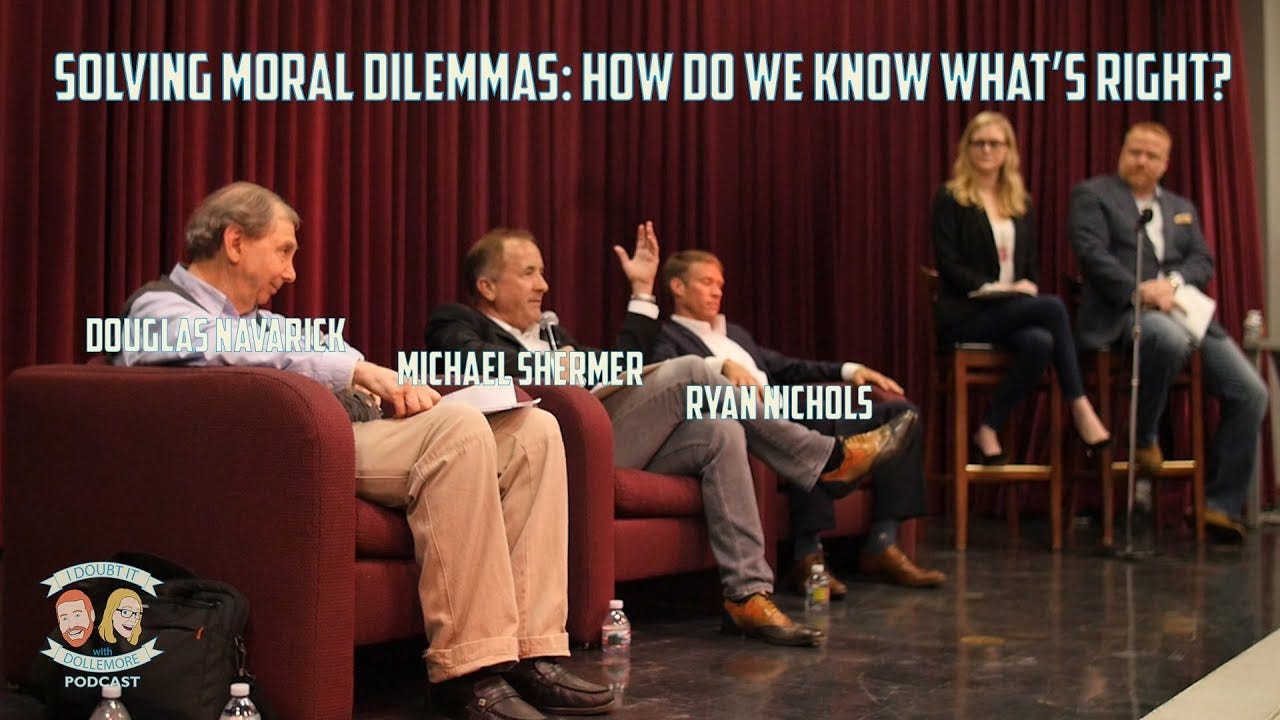

Doug and I differed on to what extent science can determine moral values (the so-called Is-Ought Fallacy, which I have argued here and here is itself a fallacy), and this led to a lively debate at Cal State Fullerton, which you can watch here:

In these articles and debate I think in many ways Doug was struggling to clarify his own religious beliefs and attitudes. In fact, in a 2015 article in Skeptic titled “The ‘God’ Construct: A Testable Hypothesis for Unifying Science and Theology,” Doug made the case that:

The current pattern of evidence for the origin of life is consistent with the interpretation that life started just once in one place and was not the result of natural and random processes.

And:

The evidence summarized in the table makes a reasonable case for the existence of a supernatural force that produced the first living cell.

Naturally, given the readership of Skeptic magazine, we received many critical commentaries and letters, and published this rebuttal. But here I will give Doug the final word as an apt way to end this tribute:

Is life God? That seems one reasonable way to characterize a supernatural force that evidence suggests may be responsible for creating the first living cell and then replicating it in endless variations. It’s debatable, but in Dawkins’ terms, it’s not delusional.

Whatever philosophical or religious elaborations one may choose to add to a minimalist construct of ‘God,’ it is intriguing to contemplate its implications. For millennia people have searched for God in meditation to erase the barriers that separate them from the greater reality. But there could be an easier way to ‘reach out to God’: just shake a hand or touch a leaf. Objectively speaking, that may be as close to God as one could ever get in this life.

Thank you Doug Navarick for a life so well lived and a mind so influential to so many people on so many subjects inherent to the human condition. You will be missed.

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the host of The Michael Shermer Show, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His new book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational.

Shermer, Michael. 1978. “Choice in Rats as a Function of Reinforcer Intensity and Quality.” Thesis presented to the faculty of California State University, Fullerton, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Psychology. Douglas J. Navarick, Committee Chair; Margaret H. White, Member; Michael J. Scavio, Member. August 8.

Herrnstein, Richard J. 1961. “Relative and Absolute Strength of Response as a Function of Frequency of Reinforcement.” Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 4, 267-272.

De Villiers, Peter A. and Richard Herrnstein. 1976. “Toward a Law of Response Strength.” Psychological Bulletin, 83, 11131-1153.

Navarick, Douglas J. 2013. “Moral Ambivalence: Modeling and Measuring Bivariate Evaluative Processes in Moral Judgment.” Review of General Psychology, Vol.17, #4, 443-452.

Navarick, Douglas J. 2012. “Historical Psychology and the Milgram Paradigm: Tests of an Experimentally Derived Model of Defiance Using Accounts of Massacres by Nazi Reserve Police Battalion 101.” The Psychological Record, 62, 133-154.

Navarick, Douglas J. 2009. “Reviving the Milgram Obedience Paradigm in the Era of Informed Consent.” The Psychological Record, 59, 155-170.

Thank you for sharing those personal and thoughtful memories of your mentor.

I can't remember where I read it but the acronym GOD stands for Good Orderly Direction of the universe. This seems apt to me as an atheist.