Remembrance of Nuclear Things Past

Putin's elevation of his nuclear arsenal to high alert forces us to recall what's at stake in the Ukraine crisis

How quickly things change. Less than a year ago, at their Geneva summit on June 15, 2021, Presidents Vladimir Putin and Joe Biden seemed to agree that the threat of nuclear war was a Cold War relic, declaring: “Nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.” Eight months later, on February 27, 2022, Putin told his top defense and military officials to put Russia’s nuclear forces in a “special regime of combat duty,” elevating to alert status his trifecta of land-, sea-, and air-based nuclear delivery systems (comparable to our own nuclear triad of land-based missiles, nuclear-missile-armed submarines, and strategic aircraft with nuclear bombs and missiles). According to Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association:

Inserting nuclear weapons into the Ukraine war equation at this point is extremely dangerous, and the United States, President Biden, and NATO must act with extreme restraint. This is a very dangerous moment in this crisis, and we need to urge our leaders to walk back from the nuclear brink.

Even if Putin is not as unhinged as many are accusing him of being for invading Ukraine, and this time he’s merely rattling his saber, accidents and contingencies could readily lead Russia, NATO, and the United States to stumble into a nuclear exchange, even if no one actually wants it. Here is how Tom Nichols, Professor of National Security Affairs at the US Naval War College, described it in an analysis in The Atlantic:

War is always a risky and unpredictable affair, even when one side is far stronger than the other. Human beings and their machines make mistakes, sometimes with dire results. In 2015, Turkey, a NATO nation, shot down a Russian jet that had strayed over the Turkish border. Two years ago, during the crisis between Iran and the United States after U.S. forces killed Qassem Soleimani, the Iranians shot down a commercial airliner—from Ukraine, no less—in their own country. And let us not forget that the Russian forces now on the march belong to the same military that in 2014 managed to screw up and shoot down a commercial airliner over Ukraine while claiming that it wasn’t even there in the first place.

There are countless opportunities for such errors in the chaos now overtaking Ukraine. The Russians might shoot at NATO aircraft after misidentifying them. Or they might incorrectly believe that Russian aircraft have been attacked by NATO forces. They might suffer a misfire or a targeting error of some kind that puts Russian ordnance on NATO territory. Europe’s a crowded continent, and no place for a jumpy trigger finger, but accidents are an unavoidable part of warfare.

Accidents are an unavoidable part of all human affairs, but nuclear weapons carry an additional risk of being the only true civilization-ending threat deserving of the adjective existential. Thus, let’s use this crisis to recall what all is at stake, which I did in the halcyon days of 2015 in my book The Moral Arc, in which I treated the threat of nuclear weapons as a relic of the Cold War, on pace with other declines in violence and aggression. Unfortunately, what I wrote then about the utter destructiveness of nuclear weapons and the madness of MAD, still applies….

The figure above shows a Civil Defense Air Raid card from the 1950s, instructing citizens to “drop and cover” in the event of a nuclear attack. As a child growing up in the early 1960s I recall our periodic Friday morning drills at Montrose Elementary School, trusting my teacher that our flimsy wooden desks would protect us from a thermonuclear blast over Los Angeles.

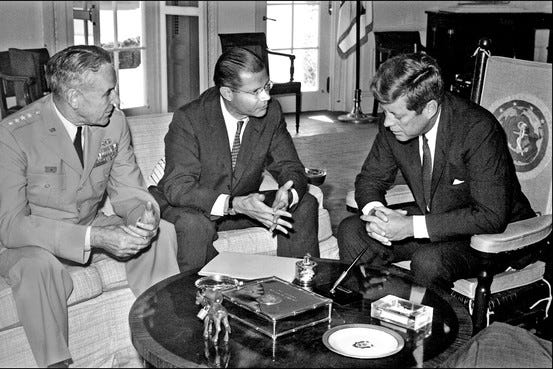

When I was an undergraduate at Pepperdine University in 1974, the father of the hydrogen bomb—Edward Teller—spoke at our campus in conjunction with the awarding of an honorary doctorate. His message was that deterrence works, even though at the time I remember thinking—like so many politicos were saying—“yeah, but a single slip-up is all it takes.” Popular films such as Fail Safe and Dr. Strangelove reinforced the point. But the slip-up never came. MAD has worked because neither side has anything to gain by initiating a first strike against the other nation—the retaliatory capability of both is such that a first strike would most likely lead to the utter annihilation of both countries (along with much of the rest of the world). “It’s not mad!” proclaimed Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara. “Mutual Assured Destruction is the foundation of deterrence. Nuclear weapons have no military utility whatsoever, excepting only to deter one’s opponent from their use. Which means you should never, never, never initiate their use against a nuclear-equipped opponent. If you do, it’s suicide.”1

The logic of deterrence was first articulated in 1946 by the American military strategist Bernard Brodie in his appropriately titled book The Absolute Weapon, in which he noted the break in history that atomic weapons brought with their development: “Thus far the chief purpose of our military establishment has been to win wars. From now on, its chief purpose must be to avert them. It can have almost no other purpose.”2 As Dr. Strangelove explained in Stanley Kubrick’s classic Cold War film (in the famous war room scene where fighting is not allowed): “Deterrence is the art of producing in the mind of the enemy the fear to attack.” Said enemy, of course, must know that you have at the ready such destructive devices, and that is why “The whole point of a doomsday machine is lost if you keep it a secret!”

Dr. Strangelove was a black comedy that parodied MAD by showing what can happen when things go terribly wrong, in this case when General Jack D. Ripper becomes unhinged at the thought of “Communist infiltration, Communist indoctrination, Communist subversion, and the international Communist conspiracy to sap and impurify all of our precious bodily fluids;” thus he orders a nuclear first strike against the Soviet Union. Given this unfortunate incident and knowing that the Russians know about it and will therefore retaliate, General “Buck” Turgidson pleads with the president to go all out and launch a full first strike. “Mr. President, I’m not saying we wouldn’t get our hair mussed, but I do say no more than ten to twenty million killed, tops, uh, depending on the breaks.”

He wasn’t far off from real projected casualties (Kubrick was a student of Cold War strategy), as computed by Robert McNamara: “What kind of amount of destruction must we be able to inflict upon the attacker in the retaliation to insure that he would indeed be deterred from initiating such an attack? In the case of the Soviet Union, I would judge that a capability on our part to destroy, say, one-fifth to one-fourth of their population and one-half of her industrial capacity would serve as an effective deterrent.”3 When he spoke these words in 1968 the population of the U.S.S.R. was about 128 million, which translates to 25-32 million dead.

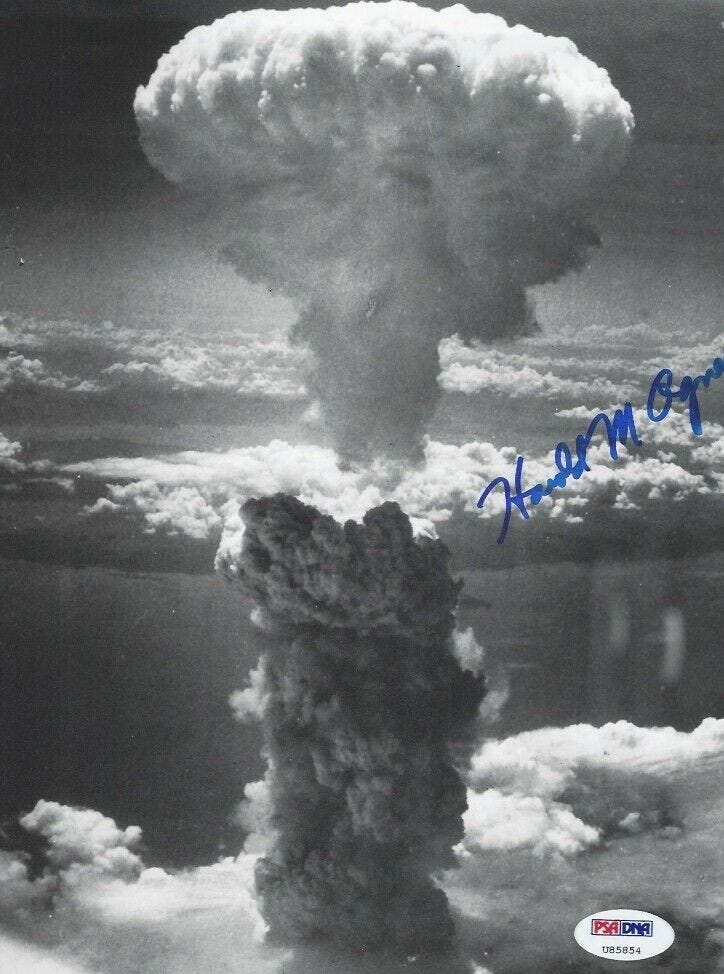

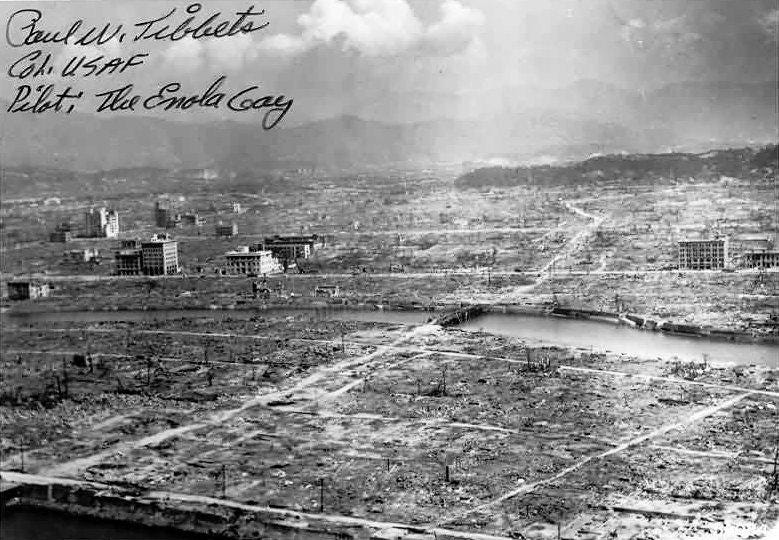

The difference was fully appreciated by Harold Agnew, who was something of a real-life Dr. Strangelove. Director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory for a decade, prior to that he worked on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos building the first atomic bombs—Fat Man and Little Boy—and he flew in a B-29 plane parallel to the Enola Gay bomber to observe and measure the yield of the explosion over Hiroshima; he even snuck onto the plane his own 16-millimeter movie camera and captured the only footage of the explosion that killed 80,000 people. Deterrence is what Agnew had in mind when he said that he would require every world leader to witness an atomic blast every five years while standing in his underwear “so he feels the heat and understands just what he’s screwing around with because we’re fast approaching an era where there aren’t any of us left that have ever seen a megaton bomb go off. And once you’ve seen one, it’s rather sobering.”4

A 1979 report from the Office of Technology Assessment for the U.S. Congress, entitled The Effects of Nuclear War, estimated that 155 to 165 million Americans would die in an all-out Soviet first strike (unless people made use of existing shelters near their homes, reducing fatalities to 110-120 million). The population of the U.S. at the time was 225 million, so the estimated percent that would be killed ranged from 49 percent to 73 percent. Staggering. The report then lays out a scenario for what would happen to one city the size of Detroit if it were hit by a 1-megaton (Mt) nuclear bomb. By comparison, Little Boy—the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima—had a yield of 16 kilotons. A 1-Mt bomb is a thousand kilotons, or the equivalent of 62.5 Little Boy bombs. Read this and consider what life would be like if this happened to your city:

A 1-Mt [megaton] explosion on the surface leaves a crater about 1,000 feet in diameter and 200 feet deep, surrounded by a rim of highly radioactive soil about twice this diameter thrown out of the crater. Out to a distance of 0.6 miles from the center there will be nothing recognizable remaining …. Of the 70,000 people in this area during nonworking hours, there will be virtually no survivors. … Individual residences in this region will be totally destroyed, with only foundations and basements remaining. … Whether fallout comes from the stem or the cap of the mushroom is a major concern in the general vicinity of the detonation because of the time element and its effect on general emergency operations. … The near half-million injured present a medical task of incredible magnitude. Hospitals and beds within 4 miles of the blast would be totally destroyed. Another 15 percent in the 4- to 8-mile distance range will be severely damaged, leaving 5,000 beds remaining outside the region of significant damage. Since this is only 1 percent of the number injured, these beds are incapable of providing significant medical assistance. … Burn victims will number in the tens of thousands; yet in 1977 there were only 85 specialized burn centers, with probably 1,000 to 2,000 beds, in the entire United States.

The report goes on like this for pages. Multiply those effect by 250 (the number of American cities believed to be targeted by the Soviet Union) and you get the report’s stark conclusion: “The effects on U.S. society would be catastrophic.”5 The catastrophe would be no less so for the Soviet Union and its allies. A 1957 report by Strategic Air Command (SAC) estimated that between 360 and 525 million casualties would be inflicted in the first week of a nuclear exchange with the Soviet block.6 Such figures are so unimaginable that it is hard to wrap our minds around them.

Post Apocalyptic Urban Landscape. Digitally generated post apocalyptic scene depicting a desolate urban landscape with buildings in ruins and cloudy sky. The scene was rendered with photorealistic shaders and lighting in UE4 (Unreal Engine 4.23) with some post-production added. Getty Images.

Deterrence has worked so far—no nuclear weapon has been detonated in a conflict of any kind since August, 1945—but it would be foolish to think of deterrence as a permanent solution.7 As long ago as 1795, in an essay entitled Perpetual Peace, Immanuel Kant worked out what such deterrence ultimately leads to: “A war, therefore, which might cause the destruction of both parties at once … would permit the conclusion of a perpetual peace only upon the vast burial-ground of the human species.”8 Kant’s book title came from an innkeeper’s sign featuring a cemetery—not the type of perpetual peace most of us strive for.

In game theory, when two players are each incentivized to up the stakes of their involvement even when neither one wants to it is called an escalation game (our wars in Vietnam and Afghanistan are examples). Coupled to loss aversion (in which losses hurt twice as much as gains feel good) and the sunk-cost bias (the tendency to continue a losing strategy because of the cost sunk into that action, as in failing investments, businesses, and marriages), such escalation games can lead to ruinous outcomes in which no one wins. Let’s hope cooler heads and rational brains prevail and Putin backs down from his nuclear saber rattling before this unfolding tragedy in Ukraine spills out into Europe and from there to the rest of the world.

Quoted in Cold War: MAD 1960-1972. 1998. BBC Two Documentary. Transcript: http://www.docusam.com/hist3209/cw12.pdf

Brodie, Bernard. 1946. The Absolute Weapon: Atomic Power and World Order. New York: Harcourt Brace, 79.

McNamara, Robert S. 1969. “Report Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Fiscal year 1969-73 Defense Program, and 1969 Defense Budget, January 22, 1969.” Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 11.

Quoted in Obituary, Los Angeles Times, October 2, 2013, AA6.

“A Soviet Attack Scenario.” 1979. The Effects of Nuclear War. Washington, D.C.: Office of Technology Assessment. Reprinted in: Swedin, Eric G. (Ed.). 2011. Survive the Bomb: The Radioactive Citizen’s Guide to Nuclear Survival. Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press, 163-177.

Brown, Anthony Cave (Ed.). 1978. DROPSHOT: The American Plan for World War III Against Russia in 1957. New York: Dial Press; Richelson, Jeffrey. 1986. “Population Targeting and US Strategic Doctrine.” In Desmond Ball and Jeffrey Richelson (Eds.). Strategic Nuclear Targeting. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 234-249.

For a scholarly analysis of and an alternative view to deterrence see: Kugler, Jacek. 1984. “Terror Without Deterrence: Reassessing the Role of Nuclear Weapons.” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 28(3), September, 470-506.

Kant, Immanuel. 1795. “Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch.” In Perpetual Peace and Other Essays. Indianapolis: Hackett, I, 6.

Born during WW2, I grew up in a world terrified of a nuclear war. In my analysis deterrence works for one reason only.

The crazy pack of psychopaths we call world leaders always act in what they see as their own best interest. Sun Tzu put it perfectly when he wrote "An evil enemy, will burn his own nation to the ground... to rule over the ashes".

Deterrence works not because of the massive destruction or the loss of life, these are factors that don't enter into the calculations of psychopaths. It works only because a nuclear war targets the leaders. If the leaders had to lead their troops into battle wars would be very rare. A nuclear exchange puts the monsters on the front line, and that works.

MMK

Scary indeed. We should consider deterrence as part of the carrot and stick combo. On the news a US general said we need to give Putin a face-saving 'way out' because if he winds up in a no-win situation no one knows what he may do.

There are many options other than Nuclear Weapons: Consider Russia's TOS thermobaric weapons - they could be nearly as devastating against a civilian population as a tactical nuke.

If Russia's troops experience more humiliation at the hands of Ukrainians defending their homes, Putin may feel the need to do something atrocious to re-establish the Russian army's reputation. He may stop short of Nukes but still do some very awful things. These things may not affect Americans but they will affect humans.