Slavery and a Moral Science of Freedom

On the 95th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday, an example of how facts and reason can determine values and morals

“In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free—honorable alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth. Other means may succeed; this could not fail. The way is plain, peaceful, generous, just—a way which, if followed, the world will forever applaud.”

—Abraham Lincoln, Annual Message to Congress, December 1, 1862

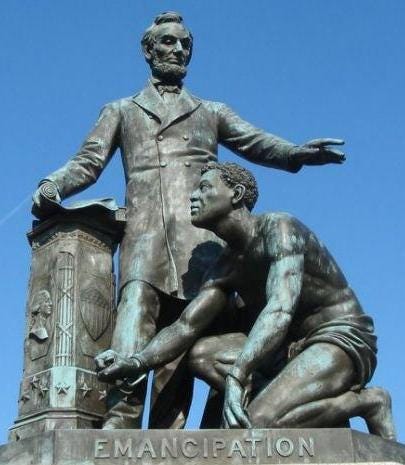

Emancipation Memorial in Lincoln Park, Washington DC

Of the many and various abuses and usurpations of humans by other humans, there is perhaps none so odious and oppressive as the ownership of one human being by another. This is slavery and it has existed for as long as there have been those who, for the life of them, can’t see the problem with having a bunch of people that they don’t have to pay doing work for them. It is a custom that relies on an unspeakable lack of empathy, on the existence of a class or caste-based, socially stratified society, and on a population and economy large enough to support it. Older than any written record, institutionalized slavery very possibly began around the time of the agricultural revolution (with its accompanying ideas about ownership) around 10,000 years ago.

Throughout these latest few millennia, religions in general, and Jewish, Christian, and Islamic churches in particular, have had little problem with the forced enslavement of hundreds of millions of people. It was only after the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment that rational arguments were proffered for the abolition of the slave trade, influenced by and citing such secular documents as the American Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man. After an unconscionably long lag time, religion finally got on board the abolition train and became instrumental in helping to propel it forward. How this unfolded is a convoluted history that I trace in Chapter 5 of my 2015 book The Moral Arc, but for this tribute to Martin Luther King Jr. on the 95th anniversary of his birth, I present a rational science-based case for why slavery is objectively and absolutely wrong.

Enlightenment Reason and the Abolition of Slavery

There is considered and considerable debate among scholars and historians about what led, ultimately, to the abolition of slavery. However, focusing strictly on the arguments, a brief review is instructive with an eye toward the arguments that were used against the institution.

Starting with religion, as the British historian Hugh Thomas noted in his monumental study The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440-1870: “There is no record in the seventeenth century of any preacher who, in any sermon, whether in the Cathedral of Saint-André in Bordeaux, or in a Presbyterian meeting house in Liverpool, condemned the trade in black slaves.”1

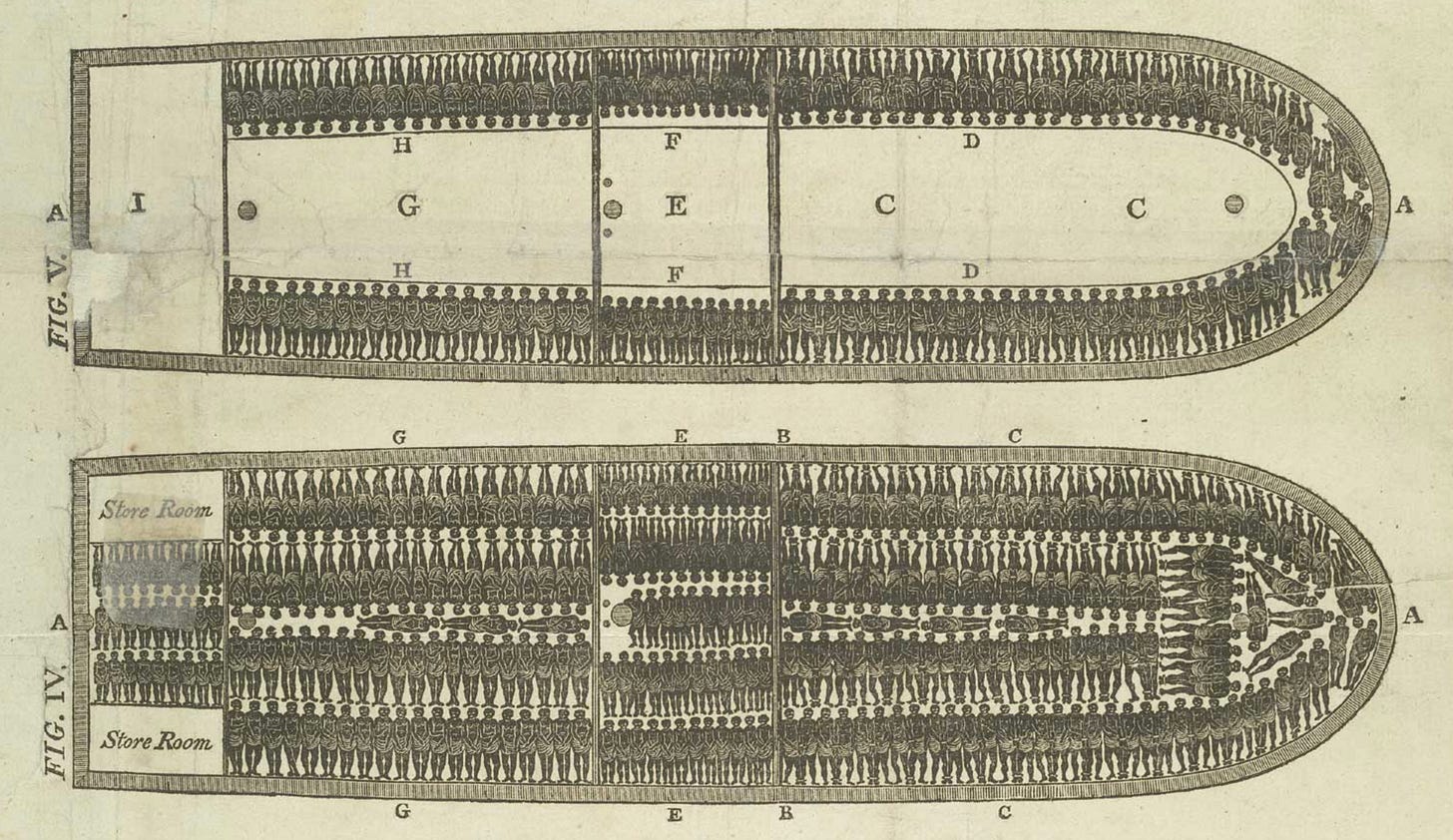

Instead, what few objections there were often had a ring of pragmatism to them, as in a 1707 letter from the secretary of the Royal Africa Company, Colonel John Pery, to his neighbor William Coward, who was considering sponsoring a slave voyage. It was “morally impossible that two tier of Negroes can be stowed between decks in four feet five inches,” he said. One tier, however, was perfectly acceptable in terms of profitability, given that the death rate on over-packed slave ships was a whopping 10 to 20 percent in the Middle Passage between Africa and America. Even religious-sounding objections were suspiciously expedient in their reasoning, as reflected in this observation by ship’s surgeon Thomas Aubrey, a doctor on the slave ship Peterborough, when he mused that the inhumanity suffered by their cargo might be compensated for in the next life: “For, though they are heathens, yet they have a rational soul as well as us; and God knows whether it may not be more tolerable for them in the latter day [of judgment] than for many who profess themselves Christians.”2

From the British Library: "This diagram of the 'Brookes' slave ship, which transported enslaved Africans to the Caribbean, is probably the most widely copied and powerful image used by those who campaigned to end the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Traders knew that many of the Africans would die on the voyage and would therefore pack as many people as possible on to their ships—in total there were 609 enslaved men, women and children on board this ship. The conditions would have been appalling. Each person occupied a tiny space in the hold. In this case they had to lie in spaces just 10 inches high and were often chained or shackled together in pairs, making movement even more difficult. The cramped conditions meant that there were high incidences of diseases such as smallpox, measles, scurvy and dysentery. Because of the long distances involved food and water was rationed and always in short supply or ran out completely."

It was not until late in the 18th century that objections to slavery were marshaled on ethical grounds, as noted by one prominent Bostonian: “About the time of the Stamp Act [1765], what were before only slight scruples in the minds of conscientious persons, became serious doubts and, with a considerable number, ripened into a firm persuasion that the slave trade was malum in se.” Evil in itself. That attitude was slow in coming. As late as 1757, the Huguenot rector of Westover, Peter Fontaine, wrote to his brother Moses about their “intestine enemies, our slaves,” noting “To live in Virginia without slaves is morally impossible.” It was also economically problematic, and as Hugh Thomas notes: “None of these prohibitions…was decided upon for reasons of humanity. Fear and economy were the motives.”3

What ultimately brought about the abolition of slavery? According to Thomas, “The great wave of ideas, and emotions, known in France, and those who followed her, as the Enlightenment, was (in contrast to the Renaissance) hostile to slavery, though not even the most powerful intellects knew what to do about the matter in practice.”4 Enlightenment ideas transformed into laws, coupled with state enforcement, is what ultimately secured the end of the practice—an end that unfolded in ever more rapid escalation once it took off in the late 18th century. Here are a handful of non-religious (secular) arguments against slavery proffered by Enlightenment philosophers that were highly influential in the abolition of slavery.

In his fictional 1756 Scarmentado, the widely read Voltaire had his African character turn the tables on a European slave trading ship captain, explaining to him why he enslaved the white crew: “You have long noses, we have flat ones; your hair is straight, while ours is curly; your skins are white, ours are black; in consequence, by the sacred laws of nature, we must, therefore, remain enemies. You buy us in the fairs on the coast of Guinea as if we were cattle in order to make us labor at no end of impoverishing and ridiculous work…[so] when we are stronger than you, we shall make you slaves, too, we shall make you work in our fields, and cut off your noses and ears.”5

The Enlightenment philosopher Montesquieu, in his highly-influential 1748 work, The Spirit of the Law, argued that slavery was bad not only for the slave but for the slave master; the former for the obvious reason that slavery prevents a person from doing anything virtuous; the latter because it leads a person to become proud, impatient, hard, angry, and cruel.6

In the entry for the slave trade in Denis Diderot’s monumental 1765 Encyclopédia, which was devoured by intellectuals throughout the continent, Great Britain, and the colonies, the author wrote, “This purchase is a business which violates religion, morality, natural law, and all human rights. There is not one of those unfortunate souls…slaves…who does not have the right to be declared free, since in truth he has never lost his freedom; and he could not lose it, since it was impossible for him to lose it; and neither his prince, nor his father, nor anyone else had the right to dispose of it.”7

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in his 1762 Du Contrat Social (The Social Contract)—which was so influential in the intellectual foundation of the United States Constitution—rejected slavery as being “null and void, not only because it is illegitimate, but also because it is absurd and meaningless. The words ‘slavery’ and ‘right’ are contradictory.”8

From the European continent secular sentiments against slavery migrated to the British Isles and were inculcated and expanded upon in the Scottish Enlightenment. In A System of Moral Philosophy, the Scottish philosopher Francis Hutcheson concluded that “all men have strong desires of liberty and property” and that “no damage done or crime committed can change a rational creature into a piece of goods void of all right.”9 Hutcheson’s student, Adam Smith, applied this principle in his first book in 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, to argue: “There is not a negro from the coast of Africa who does not…possess a degree of magnanimity which the soul of his sordid master is scarce capable of conceiving.”10

In time, such arguments found their way into the legal system, such as through the writings of the jurist and legal scholar Sir William Blackstone, whose 1769 Commentaries on the Laws of England outlined a legal case against slavery, then pronounced that “a slave or a negro, the moment he lands in England, falls under the protection of the laws and, with regard to all natural rights, becomes, eo instanti [instantly], a freeman.”11

Slavery and the Principle of Interchangeable Perspectives

Slavery is morally wrong because it’s a clear-cut case of decreasing the survival and flourishing of sentient beings. But why is that wrong? It is wrong because it violates the natural law of personal autonomy and our evolved nature to survive and flourish; it prevents sentient beings from living to their full potential as they choose, and it does so in a manner that requires brute force or the threat thereof, which itself causes incalculable amounts of unnecessary suffering. How do we know that’s wrong? Because of what Steven Pinker calls the “interchangeability of perspectives,”12 which we might elevate to a principle of interchangeable perspectives: I would not want to be a slave, therefore I should not be a slave master. If this sounds familiar, it’s because it is, in fact, the very argument made by the man who did more than anyone else in this country to put an end to slavery, Abraham Lincoln, who in 1858, on the eve of the American Civil War that would be fought to end the institution, declared: “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master.”13

This is also another way to formulate the Golden Rule: “As I would not want someone else to make me a slave, so I should not make someone else be a slave.” In modern parlance, it is a description of the evolutionary stable strategy of reciprocal altruism: “I will scratch your back instead of being your master, if you will scratch my back and not make me a slave.” It is the behavioral game theory strategy of tit-for-tat: “I won’t make you a slave if you don’t become my master.”

The principle of interchangeable perspectives is also a restatement of John Rawls’ “original position” and “state of ignorance” arguments, which posit that in the original position of a society in which we are all ignorant of the state in which we will be born—male or female, black or white, rich or poor, healthy or sick, Protestant or Catholic, slave or free—we should favor laws that do not privilege any one class because we don’t know which category we will ultimately find ourselves in.14 This can be restated in this context thusly: “As I would not want to live in a society in which I am a slave, so I will vote for laws that outlaw slavery.”

In an unpublished note penned in 1854, Lincoln outlined the argument in what to our modern ears sounds like a perfect articulation of a behavioral game analysis. In his refutation of the arguments made in his day that the races should be ranked by skin color, intellect, and economic “interest”, Lincoln wrote the following:

If A. can prove, however conclusively, that he may, of right, enslave B.—why may not B. snatch the same argument, and prove equally, that he may enslave A?

You say A. is white, and B. is black. It is color, then; the lighter, having the right to enslave the darker? Take care. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with a fairer skin than your own.

You do not mean color exactly?—You mean the whites are intellectually the superiors of the blacks, and, therefore have the right to enslave them? Take care again. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with an intellect superior to your own.

But, say you, it is a question of interest; and, if you can make it your interest, you have the right to enslave another. Very well. And if he can make it his interest, he has the right to enslave you.15

Lincoln is here making a clearly secular argument for equality, reasoning his way from premises to a conclusion, reflecting the influence on Lincoln of Euclid’s Elements of Geometry, of which he was an avid reader and made reference to the mathematical propositions and how such reasoning might apply to human affairs. In the above passage, A and B are interchangeable elements of the proposition of the right to enslave—as A would not be a slave to B, A cannot be a master to B.16

In fact, the subsequent lines to Lincoln’s formulation of the principle of interchangeable perspectives—“As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master”—are usually left off: “This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.” Lincoln’s ultimate moral avowal was simple, and he made it in April of 1864 while the body count of the Civil War had ticked up to over half a million dead:

“If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.”17

The rational arguments and scientific refutations of slavery in the 18th and 19th centuries that led to it’s legal abolition and universal denunciation set the stage for the other rights revolutions that led to greater justice and freedoms for blacks and minorities, women and children, gays and lesbians, and now even animals, and expanded the moral sphere to include more sentient beings than ever before in human history.

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, Executive Director of the Skeptics Society, and the host of The Michael Shermer Show. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His latest book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational. His next book is: Truth: What it is, How to Find it, Why it Matters, to be published in 2025.

References

Thomas, Hugh. 1997. The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440-1870. New York: Simon and Schuster, 451.

Ibid, 454-455.

Ibid, 457.

Ibid, 464.

Voltaire. Complete Works of Voltaire. (Theodore Besterman (Ed.). Banbury. 1974, Vol. 117, 374.

Montesquieu. Oeuvres Complétes. Edouard Laboulaye (Ed.). 1877. Paris, Vol. iv, I, 330.

Encyclopedie, 1765. Vol. xvi, 532.

Rousseau. Du Contrat Social. In Oeuvres Complétes. Pléide (Ed.), Vol. I, iv.

Hutcheson, Francis. 1755. A System of Moral Philosophy. London, II, 213.

Smith, Adam. 1759. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. London, 402.

Backstone, William. 1765. Commentaries on the Laws of England. I, 411-412.

Pinker, Steven. 2008. “The Moral Instinct.” The New York Times Magazine, Jan. 13, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/13/magazine/13Psychology-t.html

Lincoln, Abraham. 1858. In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. 1953 Roy P. Basler (Ed.), Volume II, August 1, 532.

Rawls, J. 1971. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge: Belknap/Harvard University Press.

Lincoln, Abraham. 1854. Fragment on Slavery. July 1. http://www.nps.gov/liho/historyculture/slavery.htm

For a book-length defense of this connection between Lincoln and Euclid see: Hirsch, David and Dan Van Haften. 2010. Abraham Lincoln and the Structure of Reason. New York: Savas Beatie.

Lincoln, Abraham. 1864. Letter to Albert G. Hodges. Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/trt027.html The line appears in the opening of a letter to the editor of the Frankfort, Kentucky, Commonwealth, Albert G. Hodges, who had journeyed from Kentucky to meet with Lincoln to discuss the recruitment of slaves as soldiers in Kentucky, which was a border state and thus the Emancipation Proclamation did not apply. Nevertheless, slaves who entered the military could gain their freedom. Lincoln wrote: “I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel. And yet I have never understood that the Presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgment and feeling.”

The author quotes: “There is no record in the seventeenth century of any preacher who, in any sermon, whether in the Cathedral of Saint-André in Bordeaux, or in a Presbyterian meeting house in Liverpool, condemned the trade in black slaves.”¹ Better research would have shown this to be inaccurate. But there are records of Quaker opposition in particular. In 1688 Dutch Quakers in Germantown, Pennsylvania, sent an antislavery petition to the Monthly Meeting of Quakers. Three Quaker abolitionists, Benjamin Lay, John Woolman, and Anthony Benezet, devoted their lives to the abolitionist effort from the 1730s to the 1760s. In 1787 the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed.

It is tragic that some modern day thinkers, people exalted by others, question and even dismiss the Enlightenment and its values.