The Fallacy of the Enneagram Personality

Guest columnist John F. Howe debunks the highly popular enneagram of personality system, popular with corporations, intelligence agencies, and mental health professionals

John F. Howe is a former business executive and management consultant certified in multiple personality tools for organizational development and executive coaching. He has taught a non-mystical, scientific version of the enneagram of personality for 30 years. A native of Britain, John has spent half his life in the U.S. and now lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. www.knowhowe.com Correspondence: howe.jf@gmail.com

The enneagram of personality (EoP) is a huge and growing global phenomenon,1 and recently “interest in the enneagram is exploding.”2 “The enneagram” has been taught at top universities, major corporations, and government intelligence agencies such as the FBI and CIA.3 It purports to provide deep insight into human nature, and its nine type profiles resonate strongly with millions of people. It is increasingly used by mental health professionals with their patients and clients.

The consensus among academic and scientific communities, however, is to reject the EoP as pseudoscience because it lacks validation and is partly based in symbology and numerology.4 Summarily dismissing the EoP, however, ignores its proven benefits and the value many gain through better understanding themselves and others. Over the last half century, as the EoP became immensely popular, a conundrum developed: how can the enneagram of personality, considered by many to be a deeply insightful model of human nature, and used by therapists, legal profilers, and intelligence analysts, stand on such a questionable foundation of mysticism?

Unlike typologies with some academic acceptance—such as the Big Five (Five-Factor Model of Personality) or the MBTI (Myers-Briggs Type Indicator)—the EoP is not a personality test. It is a set of personality profiles associated with a geometric figure (see Figure 1). Although EoP tests exist, they arrived decades after the EoP. Even the leading EoP tests—the RHETI (Riso-Hudson Enneagram Type Indicator) and the WEPSS (Wagner Enneagram Personality Style Scales) are relatively ineffective at identifying personality types.5 One best learns one’s type through reflection and insight requiring much time, study and effort. Many people report, however, that the process of discovering their enneatype was the most valuable part of their enneagram expience as they peeled back layers masking the deeper self.

Ichazo’s Blunder

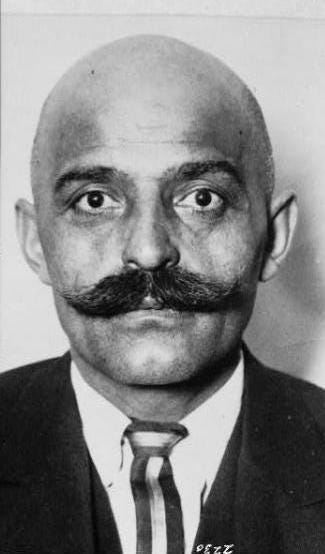

In the 1950s, the EoP was first devised by the Bolivian mystic Oscar Ichazo when he identified nine ego-types, each of which emphasizes a particular emotion: the seven deadly sins of anger, pride, envy, avarice, gluttony, lust and sloth, plus deceit and fear.

Oscar Ichazo. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Each type has a “chief feature”, which the Greek-Armenian spiritual teacher George Gurdjieff had previously described as “an axis round which everything turns.”16 Ichazo identified these chief features as the ego-fixations of resentment, flattery, vanity, melancholy, stinginess, cowardice, planning, vengefulness, and indolence.17

George Gurdjieff. Source: Wikimedia commons.

In the 1970s, the Chilean psychiatrist Claudio Naranjo M.D. mapped these nine ego-types to the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual), used by mental health professionals as a diagnostic tool,18 and expanded Ichazo’s brief type descriptions into the modern psychological type profiles of the EoP that today resonate strongly with so many people. If this was the whole story, those nine ego-types might now have been validated and scientifically accepted.

Claudio Naranjo M.D. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Unfortunately, Ichazo was very much enamored with Gurdjieff’s beloved enneagram symbol. Gurdjieff endowed the enneagram symbol with great significance, proclaiming: “What a man cannot put into the enneagram, he does not understand."9 The folly of Ichazo and Naranjo was in associating the ego-types with the enneagram symbol. There is no connection between them and no support for placing the types on the diagram. The consequences of this have been profound and have limited the utility and credibility of the EoP typology.

Strong Face Validity

The EoP’s popularity, and the passion it generates, is largely due to its high degree of apparent face validity (the extent to which an assessment tool appears to measure what it says it measures), in this case the way in which its insights resonate with people. That personal EoP experience is powerful, and for many, it is intoxicating. As people learn about the nine types, they recognize aspects of themselves, family members, and friends in a series of realizations prompting moments of profound understanding, empathy, and acceptance.

Some of these people had spent decades trying to understand themselves: their automatic thoughts, emotional patterns, and unwanted behaviors. Some had an inch-thick file of self-observations, personality test results, and personal writings, and in some cases decades spent in therapy. The nine profiles of the EoP depict personality structures that join up our islands of self-knowledge into an integrated self-concept. Spiritual teachers such as Gurdjieff spoke about the disparate “selves” or “I’s” inside each of us.9 The EoP shows how to fit together these apparently diverse aspects of self, revealing the attentional focus of one’s ego.

The Conundrum of the Enneagram

Many thousands of psychiatrists, psychologists, and therapists now use the EoP with their patients and clients because among its proven benefits reviewed by Hook, et al.,5 the EoP can “(a) promote the therapeutic alliance; (b) identify relational themes; (c) identify client strengths;10 (d) improve communication among couples and families;11 (e) provide a map of the therapeutic process; (f) help normalize clients' emotional pain; and (g) encourage clients to take ownership over their healing process.”12 Hook, et al. conclude, however, that medical authorities and professional certification bodies view clinical EoP use as a science-practice gap because of the EoP’s questionable predictive validity (the extent to which an assessment tool predicts future outcomes) and reliability (the extent to which an assessment tool consistently measures dimensions of a person over time), especially when compared to validated personality tests like the Big Five.5

This science-practice gap of the EoP has far-reaching implications. Lacking proven validity and reliability, should the EoP be used by therapists and law enforcement profilers? How does something resembling an astrological chart deliver genuine insights with predictive value? Why, after fifty years, are we no closer to resolving the paradox of the EoP’s apparent face validity versus the mysticism of its symbology and numerology?

This paper resolves the enneagram conundrum by examining the following questions:

Which aspects of EoP theory are supported by research and which are not?

Why have investigators failed to evaluate the EoP’s fundamental assumptions?

How can mental health professionals avoid the EoP science-practice gap?

How can this typology move past its pseudoscience and gain academic acceptance?

The Religion of the Enneagram

The EoP’s validity conundrum has resisted resolution for more than fifty years because there exists: (1) a multitude of layered and interrelated EoP theories that complicate study and analysis; (2) a lack of rigorous, objective analysis to separately evaluate individual aspects of EoP theory and its fundamental assumptions; and (3) as review papers state: only two of the more than 100 published EoP papers are based on formal studies.5

Most traditional enneagram teaching is common across authors and teachers. It is repeated in more than a thousand published books, in professional enneagram trainings, and in public classes, claiming that the enneagram system of personality has ancient roots (incorrect: only the geometric figure itself is old), and that it is timeless wisdom originating from the Sufis, mystical Christianity, or the Kabbalah13 (incorrect: the personality model was developed in the 1950s through the 1970s by Oscar Ichazo and then Claudio Naranjo).

The leading EoP authorities say, often in reverential tones, that the enneagram symbol itself is sacred (incorrect: it is inherently no more sacred than a parallelogram) and that the position of each personality type on the symbol is pre-ordained by numerology from the Law of Three and the Law of Seven’s cyclic decimal 14285714 (incorrect: the numbers were deliberately arranged that way on the diagram about sixty years ago by Ichazo because he believed in numerology).

Enneagram teachers explain that the numbers adjacent to each type are their “wings” (see Figure 2). Some say personalities are influenced by one or both wings, and others15 state every person has one wing but not the other, so, in fact, there are not nine types, but eighteen (incorrect: there is no evidence whatsoever for the existence of wings, which depend entirely on the mistaken association of the ego-types with the enneagram symbol).

Enneagram authors and teachers15 claim that the lines connecting the types (see Figure 3) can be seen as arrows (of integration/disintegration) showing characteristics each type displays when at their best and worst (incorrect: according to his student Mel Risman, Naranjo first sketched the arrows “as a doodle” and was shocked others then taught this). It is also standard teaching15 that the position of the types on the symbol indicates whether each type is in the gut (8, 9, 1) heart (2, 3, 4) or head (5, 6, 7) triad (incorrect: there is no scientific support for the triad conjecture).

Enneagram Mythmaking

The preceding information is standard EoP teaching. It has been widely published and taught to millions of people. Not one word of it is correct. In court records,16 Ichazo said he received the enneagram of personality from the Jewish archangel Metatron in “a vision of 108 enneagons.” By claiming he did not invent the enneagram of personality, but discovered it through this mystical vision, Ichazo undermined his intellectual property claims and, worse, he implied the enneagram of personality had an ancient, mystical backstory, which it doesn’t.

Later, Ichazo changed his mind, saying “I did not receive this material from any archangel or entity whatsoever ... it was the fruit of a long, careful, and dedicated study of the human psyche and the main problems of philosophy and theology.”17 Naranjo elucidated: “Lately Ichazo has been claiming more authorship of the enneagram than he did,” explaining this was an appropriate reaction to how his teaching was distorted and popularized against his wishes by those who attended his early groups.14

The widely taught enneagram of personality endorsed by the International Enneagram Association (IEA) bears the hallmarks of a fringe religion. It is based on a mystic’s vision, involves otherworldly beings, requires unsubstantiated belief, uses numerology and symbology, and continues to accrete increasingly bizarre theories. As with many such belief systems, it has a large number of devout adherents.

Research suggests the EoP’s nine ego-types have at least some validity, but their inter-relationship and all secondary and tertiary aspects of enneagram theory are invalid.5 In other words, the problem with the enneagram of personality is the enneagram symbol itself. Removing the symbol and everything associated with it resolves the EoP conundrum and demystifies the typology. This is as easy to write as it is difficult for the EoP community to accept.

The Entrenchment of the Enneagram Industry

When discussing such demystification with people in the enneagram community—such as EoP authors and teachers, members of the IEA (International Enneagram Association), or those who make much of their income from EoP-related activity—one is met with wide-eyed stares and incredulity. Perhaps they perceive such objective assessment of the EoP as an existential threat to their livelihood, belief system, or self-esteem. Most will not even engage in such a discussion.

Instead, they argue that it does not matter whether there is evidence to support its numerology and symbology, because the enneagram “works”, and because people “find value” in the elegance of the symbol along with its triads, wings, arrows and other ancillary theories. But, according to the results of EoP research,5 it is only the core nine ego-types that might actually “work”. Tertiary theories such as TriTypes, Dyads, and Harmonic Types can therefore be summarily dismissed because they are constructed on the unsupported secondary conjectures.

The scientific skeptic Robert Todd Carroll included the Enneagram in The Skeptic’s Dictionary, a book of pseudoscientific theories that "can't be tested because they are so vague and malleable that anything relevant can be shoehorned to fit the theory."18 Those “pseudoscientific theories” are the folly associated with, or constructed upon, the symbology and numerology of the enneagram of personality. When they are removed, we are left with a testable typology of nine ego-types.

Wings and Arrows

As with astrological charts and horoscopes, many people see aspects of themselves in the enneagram’s wings and arrows. This is exactly what one would expect from the Barnum Effect and confirmation bias.19 The enneagram industry protests: “But what is the harm if some people find value in wings and arrows?” The harm is very great. Without a validated, reliable test instrument, it is a difficult exercise for most people to correctly type themselves, an exercise made vastly more difficult by the misinformation of wings and arrows. A woman thinks to herself:

I care a lot about my appearance. I’m high energy and when I get on a roll I can really perform. This seems like the Type 3. But once in a while, I get depressed, which isn’t like a 3. Of course, that must be my 4 wing expressing itself, 4s get depressed. Okay, I’ve got it—I’m a 3w4: a 3 with a 4 wing. The thing is though; this doesn’t explain why I sometimes feel edgy and need to go through future scenarios, over-planning things in my head. Ah, I get it now: that’s when my 3 goes to 6 along the arrow.

The trouble with all this convoluted reasoning is that this poor woman is actually a 7, which better explains these self-observations. Without the wings and arrows that she has introduced to justify her mistyping as a 3, it would be much easier for her to see her correct type.

Theories of Childhood Origin

Enneagram authors posit varying theories about how enneatype develops and why someone is a particular enneagram number. Most of these theories relate how childhood experiences shape a person’s ego as a means of coping with life, such as Helen Palmer’s “1s report being heavily criticized or punished when they were young then became obsessed with trying to be good,”20 Don Riso and Russ Hudson’s “Everyone’s basic personality type is the result of having had a primary orientation to his or her nurturing-figure,”21 and Michael Goldman’s “Unlike Ones and Eights who were punished as children....”22

These theories of “childhood origin” assume a baby is born as a blank slate with few, if any, personality predispositions, but those theories are not supported by scientific research. Beyond the obvious errors in these writings, is the untold damage done to those who believe them and consequently view their personality as pathology, and blame their childhood caregivers for perceived issues. What these authors have failed to understand is that what is remembered from one’s childhood is not the cause of ego-type; it is the result of ego-type. The experiences we encode as memories, according to the arousal theory of memory formation, are those we felt strong emotion around, and we recall what we were most sensitive about.23

Type 1s are not 1s because they were criticized by their parents; Type 1s recall being criticized by their parents because they are Type 1s. When Type 1s are interviewed, those moments of childhood criticism are what they recall because of the selectivity of memory, both in terms of which memories were originally formed and what is later recalled. In fact, those recalled incidents did not cause the Type 1 fixation; they are recalled because the Type 1 fixation was already operating at that time, and the child was therefore sensitive to such events. And that is why such experiences were more deeply and frequently encoded as memory engrams.

So what does cause someone to be a type 1? The late Professor David Daniels, Head of Stanford University’s psychiatry department, wrote about a study conducted on newborn infants by Thomas and Chess.24 It discerned nine distinct behavior patterns in the babies that map directly to the nine ego-types of the EoP:

Rhythmicity/Regularity 1 - Perfectionist

Approach 2 - Helper

Activity Level 3 - Performer

Quality of Mood 4 - Individualist

Threshold of Response 5 - Observer

Attention Span 6 - Defender

Adaptability 7 - Enthusiast

Intensity of Response 8 - Asserter

Distractability 9 - Mediator

The researchers had no knowledge of the EoP or its ego-types. This study suggests that our ego-type, as defined by the nine attentional styles of the EoP, is not something formed during childhood, but something innate. David Daniels explained it this way:

Studies repeatedly demonstrate that temperament is largely the result of heredity and what is called “the non-shared family environment.” … I believe that what the behavioral geneticists and developmental psychologists call inherited temperament traits are the result of inborn propensities to develop an attentional style or habit of attention. These styles are the lenses with which we view or perceive the world, literally from birth.25

These analyses suggest that our attentional ego-type—far from being determined by childhood caregivers—was likely already set by the time we are born, and probably determined by genetic predispositions shaped by environmental factors, substantially in vitro.

Conclusion

The enneagram community wants reconciliation between the EoP and science, but that cannot happen because the enneagram is inherently mystical in nature. Such scientific acceptance can only be achieved by removing the enneagram symbol along with the numerology and all associated secondary and tertiary aspects of EoP theory. Although what remains may not make a pretty diagram with mass-market appeal, it is a more powerful typology that might be properly validated and integrated with existing research.

The science-practice gap of mental health professionals using the EoP with patients can be resolved by focusing on only the core nine ego-types, ignoring the enneagram symbol along with secondary aspects such as wings, arrows, and triads, and rejecting theories of childhood type origin. By doing so, we might, as Sam Harris wrote, “pluck the diamond from the dunghill of esoteric religion.”26

References

1. Alexander, M & Schnipke, B. (2020). The Enneagram: A Primer for Psychiatry Residents. The American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal, March.

2. Gerber, M. (2020). The Enneagram is having a moment. You can thank millennials. Los Angeles Times. April 22.

3. Seligman, J. & Joseph, N. (1994). To Find Self, Take a Number. Newsweek, September 12.

4. Thyer, B. A. & Pignotti, M. (2015). Pseudoscience in Clinical Assessment. Science and Pseudoscience in Social Work Practice. Springer Publishing.

5. Hook JN, Hall TW, Davis DE, Van Tongeren DR, Conner M. (2020). The Enneagram: A systematic review of the literature and directions for future research. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2020; 1–19.

6. Ouspensky, P. D. (1957). The Fourth Way. Routledge and Kegan Paul.

7. Naranjo, C. (1990). Ennea-type Structures: Self-Analysis for the Seeker. Gateways/IDHHB Inc.

8. Naranjo, C. (1994). Character and Neurosis – An Integrative View. Gateways/IDHHB Inc.

9. Ouspensky, P. D. (1949). In Search of the Miraculous. Harvest/HBJ Book.

10. Tapp, K., & Engebretson, K. (2010). Using the Enneagram for client insight and transformation: A type eight illustration. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 5(1), 65–72.

11. Matise, M. (2018). The enneagram: An enhancement to family therapy. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-018-9471-0

12. Choucroun, P. M. (2012). An exploratory analysis of the enneagram typology in couple counseling: A qualitative analysis (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Texas at San Antonio, TX.

13. Palmer, H. (1991). The Enneagram: Understanding Yourself and the Others In Your Life. HarperOne.

14. Naranjo, C. (1996). The Distorted Enneagram (interview). Gnosis Magazine. Fall.

15. Enneagram Institute, The. (2024). How the enneagram system works. February 28. https://www.enneagraminstitute.com/how-the-enneagram-system-works/

16. Arica Institute, Inc. v. Palmer, 761 F., Supp. 1056 (S.D.N.Y. 1991), April 9. https://shorturl.at/axCmF

17. Ichazo, O. (n.d.) https://www.skepdic.com/enneagr.html

18. Carroll, R. T. (2011). The Skeptic's Dictionary: A Collection of Strange Beliefs, Amusing Deceptions, and Dangerous Delusions. John Wiley & Sons.

19. Fayard, J. (2019). When Personality Test Results Are Wrong, But Feel So Right. Psychology Today. Sept. 29. https://shorturl.at/3U0wd

20. Palmer, H. (1991). The Enneagram: Understanding Yourself and the Others In Your Life. HarperOne.

21. Riso, D. & Hudson, R. (1996). Personality Types — Using the Enneagram for Self-Discovery. Houghton Mifflin.

22. Goldberg, M. (1999). The 9 Ways of Working. Da Capo Lifelong Books.

23. Tambini, A., Rimmele, U., Phelps, E. A. & Davachi, L. (2017). Emotional brain states carry over and enhance future memory formation. Nature Neuroscience, 20, pp. 271–278

24. Thomas, A., Chess, S. and Birch, H. G. (1970). The Origin of Personality, Scientific American, August, pp 102-109.

25. Daniels, D. (2001). Ch. 14: Nature and Nurture: On Acquiring a Type. Enneagram Applications. Metamorphous Press.

26. Harris, S. (2015). Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion. Simon & Schuster.

Most licensed mental health professionals I know consider these personality assessments a form of astrology and don’t take them seriously.

Your article touches on an important issue, but it brings to mind a broader concern in scientific discourse today—the increasing emphasis on measurement over value. The sheer volume of studies, data, and publications is staggering, yet how much of it truly advances our understanding? Science, like literature, should strive for lasting impact, not just accumulation.

This reminds me of Alice’s conversation with the Caterpillar in Alice in Wonderland:

“Who are you?” said the Caterpillar.

This was not an encouraging opening for a conversation. Alice replied, rather shyly, “I—I hardly know, Sir, just at present—at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.”

“What do you mean by that?” said the Caterpillar, sternly. “Explain yourself!”

“I can’t explain myself, I’m afraid, Sir,” said Alice, “because I am not myself, you see.”

This is particularly relevant to the Enneagram. It is a tool with great potential for insight, but its value lies in the depth of understanding it encourages, not in an attempt to quantify every nuance. When something designed to illuminate personal and psychological growth is reduced to mere metrics, it risks losing its transformative power. The Enneagram should be used as a guide for meaningful self-discovery, not as a system to be battered into rigid categorisations. With respect, I believe adding celebrity names to the Enneagram diagram detracts from its purpose.

Perhaps it is time to step back and ask: are we truly seeking knowledge, or merely accumulating data? Depth of understanding, not just measurement, is what gives knowledge its true worth. In focusing too much on quantifying everything, we risk losing the richness that makes exploration—whether scientific or personal—so valuable.