The Magisterium of Religion

The Köln Dom is a reminder of the power of faith in a pre-modern world lit only by fire and plagued by poverty, disease, misery, and early death

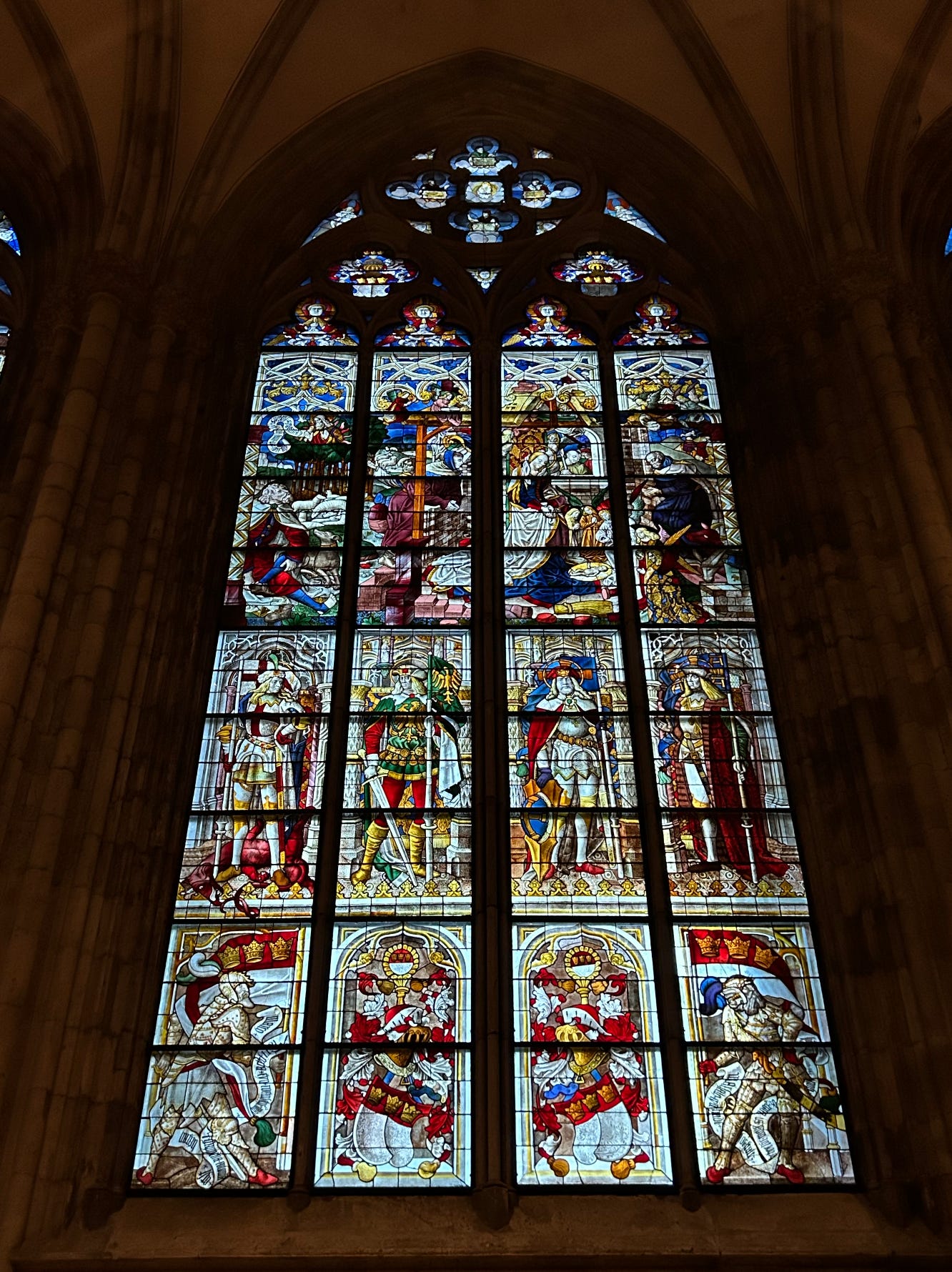

Every year for the past decade that my wife and I have returned to her home city of Köln, Germany, we make a point of visiting the magnificent cathedral in the city center that has defined the region for nearly eight centuries. Construction begun in 1248, this multi-generational project wasn’t officially completed until 1880 (and upgraded, repaired, and refurbished ever since)—six centuries of unfinished awe rising up from the banks of the mighty Rhine River that cuts through the heart of this ancient city whose pre-Medieval Roman ruins lie strewn about the landscape. It is nearly impossible for even the most jaded modern mind to be unimpressed by this architectural wonder whose ornamental details bring to life biblical chronicles and heroes.

Throughout three decades of countless articles and multiple books I have criticized religion, both its dependence on supernatural epistemology and its tribal divisiveness that led to centuries of wars, pogroms, purges, and witch hunts. But on this trip to the Cologne Cathedral I time-traveled back to the latter Middle Ages and into the late Medieval mind to imagine what it must have been like to experience the awe-inspiring magnificence of such a culturally-dominant edifice that literally and figuratively puts all other structures in the shade. Imagine walking into this sanctuary after a long and exhaustive journey from one’s provincial countryside and spartan abode…

And think about what it must have been like to hear the angelic voices of divine organ music with its 20 Hertz undertones of infrasound that unconsciously generates at once feelings of awe, fear, and trembling…

And picture the joy of children playing in the footsteps of the largest construction project anyone had ever seen or would ever experience…

To fully feel that world let’s go back to a time when civilization was lit only by fire, centuries ago when populations were sparse and 80 percent of everyone lived in the countryside and were engaged in food production, largely for themselves. (I reconstruct this worldview in detail in How We Believe and The Moral Arc.) Cottage industries were the only ones around in this pre-industrial and highly-stratified society, in which one-third to one-half of everyone lived at subsistence level and were chronically under-employed, underpaid, and undernourished. Food supplies were unpredictable and plagues decimated weakened populations.

All major cities were hit hard by disease contagions. In the century spanning 1563 to 1665, for example, there were no fewer than six major epidemics that swept through London alone, each of which annihilated between a tenth and a sixth of the population. The death tolls are almost unimaginable by today’s standards: 20,000 in 1563, 15,000 in 1593, 36,000 in 1603, 41,000 in 1625, 10,000 in 1636, and 68,000 in 1665, all in one of the world’s major metropolitan cities that had only a tiny fraction of the populations of today. Childhood diseases were unforgiving, felling 60 percent of children before the age of 17. As one observer noted in 1635, “We shall find more who have died within thirty or thirty-five years of age than passed it.” The historian Charles de La Ronciére provides examples from 15th century Tuscany in which lives were routinely cut short:

Many died at home: children like Alberto (aged ten) and Orsino Lanfredini (six or seven); adolescents like Michele Verini (nineteen) and Lucrezia Lanfredini, Orsino’s sister (twelve); young women like beautiful Mea with the ivory hands (aged twenty-three, eight days after giving birth to her fourth child, who lived no longer than the other three, all of whom died before they reached the age of two); and of course adults and elderly people.

And this does not include, La Ronciére adds parenthetically, the deaths of newborns, which historians estimate could have been as high as 30 to 50 percent.

Since magical thinking is positively correlated with uncertainty and unpredictability, we should not be surprised at the level of superstition given the grim vagaries of pre-modern life. There were no banks for people to set up personal savings accounts during times of plenty to provide a cushion of comfort during times of scarcity. There were no insurance policies for risk management, and few people had much personal property to insure anyway. With homes constructed of thatched roofs and wooden chimneys in a darkness broken only by candles, fires would routinely devastate entire neighborhoods. As one chronicler noted: “He which at one o’clock was worth five thousand pounds and, as the prophet saith, drank his wine in bowls of fine silver plate, had not by two o’clock so much as a wooden dish left to eat his meat in, nor a house to cover his sorrowful head.” Alcohol and tobacco were essential anesthetics for the easing of pain and discomfort that people employed as a form of self-medication, along with the belief in magic and superstition to mitigate misfortune.

Under such conditions it’s no wonder that almost everyone believed in sorcery, werewolves, hobgoblins, astrology, black magic, demons, prayer, providence, and, of course, witches and witchcraft. As Bishop Hugh Latimer of Worcester explained in 1552: “A great many of us, when we be in trouble, or sickness, or lose anything, we run hither and thither to witches, or sorcerers, whom we call wise men…seeking aid and comfort at their hands.” Saints were worshiped and liturgical books provided rituals for blessing cattle, crops, houses, tools, ships, wells, and kilns, along with special prayers for sterile animals, the sick and infirm, and even infertile couples. In his 1621 book, Anatomy of Melancholy, Robert Burton noted, “Sorcerers are too common; cunning men, wizards, and white witches, as they call them, in every village, which, if they be sought unto, will help almost all infirmities of body and mind.”

As well, in these late Medieval times 80-90 percent of people were illiterate. Those few who could read the local vernacular, could not read the Bible because it was written in Latin, guaranteeing that it would remain the exclusive intellectual property of an elite few. Almost everyone believed in some form of black magic. If a noble woman died, her servants ran around the house emptying all containers of water so her soul would not drown. Her Lord, in response to her death, faced east and formed a cross by laying prostrate on the ground, arms outstretched. If the left eye of a corpse did not close properly, the soul could spend extra time in purgatory (this belief led to the ritual closing of the eyes upon death). A man knew he was near death if he saw a shooting star or a vulture hovering over his home. If a wolf howled at night the one who heard him would disappear before dawn. Bloodletting was popular. Plagues were believed to be the result of an unfortunate conjuncture of the stars and planets. And the air was believed to be invested with such soulless spirits as unbaptized infants, ghouls who pulled out cadavers in graveyards and gnawed on their bones, water nymphs who lured knights to their deaths by drowning, drakes who drug children into their caves beneath the earth, and vampires who sucked the blood of stray children.

Was everyone in the pre-scientific world so superstitious? They were. As the historian Keith Thomas notes, “No one denied the influence of the heavens upon the weather or disputed the relevance of astrology to medicine or agriculture. Before the seventeenth century, total skepticism about astrological doctrine was highly exceptional, whether in England or elsewhere.” And it wasn’t just astrology. “Religion, astrology and magic all purported to help men with their daily problems by teaching them how to avoid misfortune and how to account for it when it struck.” With such sweeping power over people, Thomas concludes, “If magic is to be defined as the employment of ineffective techniques to allay anxiety when effective ones are not available, then we must recognize that no society will ever be free from it.”

That may well be, but the rise of science diminished this near universality of magical thinking by proffering natural explanations where before there were predominately supernatural ones. The decline of magic and the rise of science was a linear ascent out of the darkness and into the light. As empiricism gained status, there arose a drive to find empirical evidence for superstitious beliefs that previously needed no propping up with facts.

This attempt to naturalize the supernatural carried on for some time and spilled over into other areas. The analysis of portents was often done meticulously and quantitatively, albeit for purposes both natural and supernatural. As one diarist privately opined on the nature and meaning of comets: “I am not ignorant that such meteors proceed from natural causes, yet are frequently also the presages of imminent calamities.” Yet the propensity to portend the future through magic led to more formalized methods of ascertaining causality by connecting events in nature—the very basis of science.

In time, natural theology became wedded to natural philosophy and science arose out of magical beliefs, which it ultimately displaced. By the 18th and 19th centuries, astronomy replaced astrology, chemistry succeeded alchemy, probability theory displaced luck and fortune, insurance attenuated anxiety, banks replaced mattresses as the repository of people’s savings, city planning reduced the risks from fires, social hygiene and the germ theory dislodged disease, and the vagaries of life became less vague.

Before all this modernity came online, however, it was the magisterium of religion that soothed suffering souls, a power on poignant display in the Köln Dom.

P.S. In my 2000 book How We Believe, I argued that one role of religion is to reinforce norms, customs, and mores of a culture—along with the moral tenets of the faith—through belief of an invisible eye in the sky. On this latest visit I noticed that on the plaza surrounding the Dom, modern eyes in the sky have been added, just in case...

###

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the host of The Michael Shermer Show, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His new book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational.

Physical and social conditions in the Middle Ages certainly reinforced magical thinking. But are people much different today?

Most of us are still illiterate, especially in the languages of science and technology, but also in economics, psychology, and even history and geography. We crave mystical leaders and put unquestioned faith in preferred narratives, supported by semi-fictional media. We imagine endless apocalyptic scenarios that justify delusional visions that we seek to impose on others. And, of course, some of us take advantage of these human tendencies to control us and advance their own agenda.

Perhaps we are doomed to magical thinking until (if?) some post-human brain evolves.

As I've said before, there are only three positive things the Christian religion has contributed to mankind - Architecture, Art and Music.