The Shroud of Turin

The History and Legends of the World’s Most Famous Relic, by Andrea Nicolotti

Religious and spiritual people say that everything happens for a reason and nothing happens by chance. I’m beginning to think they might be on to something. On May 15, 2024, I posted on X a reply to Naomi Wolf’s posted image of the famed Shroud of Turin—believed by many people to be the burial cloth of Jesus—noting that it was…

Debunked decades ago as a 14th century forgery. If the basis of religious belief is faith, why do believers continue to insist they have physical evidence—here in the form of a burial shroud of someone whom a 1st century Jew would resemble not at all.

I have no idea what Wolf’s intent was in her post that lacked commentary, but I was surprised to see so many people in the replies to my post tell me that, in fact, the Shroud of Turin had not been debunked:

By chance (or was it?), shortly after this post my friend, colleague and historian of science Massimo Pigliucci wrote me from, of all places, Turin, in northern Italy, where he happened to be “teaching a course on the relationship between science and religion.” It turns out that Massimo’s host is Andrea Nicolotti, one of the world’s leading experts on and author of a book about The Shroud of Turin: The History and Legend of the World’s Most Famous Relic, suggesting that perhaps we might like to publish an excerpt from in Skeptic. Dr. Nicolotti’s book outlines the most important facts about the shroud, its history, authenticity, and claimed miraculous origin, and why it is almost certainly not the burial shroud of Jesus, and so I am please to present this excerpt from the book.

Dr. Andrea Nicolotti is Full Professor of History of Christianity and Churches in the Department of Historical Studies, University of Turin. He focuses on the methodology of historical research, Greek translations of the Old Testament, ancient Christianity, and the history of the relics. He wrote a book on the practice of exorcism in early Christianity (Esorcismo cristiano e possessione diabolica, 2011), a history of the Image of Edessa (From the Mandylion of the Edessa to the Shroud of Turin, 2014), and The Shroud of Turin (2019).

The Shroud of Turin

By Andrea Nicolotti

For over a decade I have devoted myself to studying the Shroud of Turin, along with all the faces of sindonology (from the Greek word sindòn, used in the Gospels to define the type of fine fabric, undoubtedly linen, with which the corpse of Jesus was wrapped), or the set of scientific disciplines tasked with determining the authenticity of such relics. My work began with an in-depth analysis of the theory linking the Knights Templar to the relic,[1] and the theory according to which the Mandylion of Edessa (more on this below) and the Shroud are one and the same.[2] Studying the fabric also revealed that the textile has a complex structure that would have required a sufficiently advanced loom, i.e. a horizontal treadle loom with four shafts, probably introduced by the Flemish in the 13th century, while the archaeological record provides clear evidence that the Shroud is completely different from all the cloths woven in ancient Palestine.[3]

The result of my research is The Shroud of Turin: The History and Legends of the World’s Most Famous Relic.[4] As a historian, I was more interested in the history of the Shroud than in determining its authenticity as the burial cloth of Jesus, although the evidence is clear that it is not. However, for a historiographical reconstruction seeking to address the history of the relationship between faith and science in relation to relics, the Shroud offers a useful case for understanding how insistence on the relic’s authenticity, alongside a lack of interest on the part of mainstream science, leaves ample room for pseudoscientific arguments.

Relics

The Christian cult of relics revolves around the desire to perpetuate the memory of illustrious figures and encourage religious devotion towards them. Initially limited to veneration of the bodies of martyrs, over the centuries it extended to include the bodies of saints and, finally, objects that had come into contact with them. As Christianity spread, the ancient custom of making pilgrimages to the burial places of saints was accompanied by the custom of transferring their relics (or parts of them) to the furthest corners of the Christian world. These transfers, called “translations," had several effects:

1. They increased devotion towards the person from whom the relic derived.

2. They were believed to protect against war, natural disasters and disease, and to attract healings, conversions, miracles, and visions.

3. They heightened interest in the place hosting the relics, turning them into poles of attraction for pilgrims and enriching both the church and the city that housed them.

4. They increased the prestige of the owners of relics.

Relics are objects without intrinsic or objective value outside of a religious environment that attributes a significance to them. In a religious environment, however, they become semiophores, or “objects which were of absolutely no use, but which, being endowed with meaning, represented the invisible.”[5] However, enthusiasm for relics tended to wane over time unless it was periodically reawakened through constant efforts or significant events, such as festivals, acts of worship, translations, healings, apparitions, and miracles. When a relic fails to attract attention to itself, or loses such appeal, it becomes nearly indistinguishable from any other object.

For a long time, many scholars did not consider relics to be objects deserving of interest to professional historians because the cult of veneration surrounding them was regarded as a purely devotional set of practices largely associated with less educated classes. Conversely, the intense interest in relics—like the Shroud of Turin—engages people from all social ranks and brings together different social classes in pursuing the same religious interest. For some people, the Shroud even represents the physical evidence of what is claimed to be the greatest miracle in the history of Christendom—the resurrection of Jesus.

As the demand for relics grew among not only the faithful masses but also illustrious abbots, bishops, prelates, and princes, the supply inevitably increased. One of the effects of this drive was the frenzied search for ancient relics in holy places. Though the searches were often conducted in good faith, our modern perspective, equipped with greater historical and scientific expertise, can hardly consider most of these relics to be authentic. It was thus almost inevitable that a category of relics intermediaries and dealers emerged, some honest brokers and some dishonest fraudsters. So many were the latter that Augustine of Hippo famously spoke out against the trade in martyrs’ relics as early as the 5th century.

The Matter of Relic Authenticity

Historians who study relics from the perspective of the history of piety, devotion, worship, beliefs, secular or ecclesiastical politics, and social and economic impact, should also speak to the origin of such relics, and hence their authenticity. In the case of relics of lesser value—those that have been downgraded, forgotten, undervalued, or removed from worship—historians’ task is relatively simple. By contrast, historians and scientists face greater resistance when dealing with fake relics that still attract great devotional interest. In order to avoid criticism, many historians sidestep the authenticity issue by overlooking the question of the relic’s origin, instead focusing only on what people have believed over time and the role of the relic in history.

While this approach is legitimate, what people most want to know about holy relics like the Shroud of Turin today is their authenticity, particularly during the Age of Science with its emphasis on evidence-based belief. Unfortunately for believers in the Shroud and related relics, the likelihood of being fake becomes almost 100 percent when it has to do with people who lived at the time of Jesus or before.

The Shroud of Turin is part of the trove of Christ-related relics that were never mentioned in ancient times. When the search for relics in the Holy Land began—with the discovery of the cross, belatedly attributed to Helena, mother of the emperor Constantine—no one at that time ever claimed to have found Jesus’ burial cloths, nor is there any record of anyone having thought to look for them.

Helena of Constantinople with the Holy Cross, by Cima da Conegliano, 1495 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

The earliest travel accounts of pilgrims visiting the sites of Jesus in the 4th century show that people venerated various relics, but they do not mention a shroud. By the beginning of the 6th century, pilgrims to Jerusalem were shown the spear with which Jesus was stabbed, the crown of thorns, the reed and sponge of his passion, the chalice of the Last Supper, the tray on which John the Baptist’s head was placed, the bed of the paralytic healed by Jesus, the stone on which the Lord left an imprint of his shoulders, and the stone where Our Lady sat to rest after dismounting from her donkey. But no shroud.

It was not until the second half of the 6th century that pilgrims began to mention relics of Jesus’ burial cloths in Jerusalem, albeit with various doubts as to where they had been preserved and what form they took. The next step was the systematic and often unverified discovery of additional relics from the Holy Land, including the bathtub of baby Jesus, his cradle, nappy, footprints, foreskin, umbilical cord, milk teeth, the tail of the donkey on which he entered Jerusalem, the crockery from the Last Supper, the scourging pillar, his blood, the relics of the bodies of Jesus’ grandparents and the Three Wise Men, and even the milk of the Virgin Mary and her wedding ring.

Obviously, objects related to Jesus’ death and resurrection could easily be included in such a list. Moreover, the movement of relics from Jerusalem—bought, stolen, or forged—reached its peak at the time of the Crusades. The Carolingian era, dawning at the beginning of the 9th century, was a time of intense traffic in relics. One legend, built up around Charlemagne himself, held that he had made a journey to Jerusalem and obtained a shroud of Jesus. According to this legend, the cloth was then taken to the imperial city of Aachen (AKA Aix-la-Chapelle), then perhaps to Compiègne. There are accounts of a shroud in both cities, and Aachen still hosts this relic today.

The coexistence of these relics in two important Carolingian religious centers has not prevented other cities from claiming to possess the same objects. Arles, Rome, and Cadouin all boast a shroud, although in 1933 the one in Cadouin was revealed to be a medieval Islamic cloth. Carcassonne likewise makes this claim, even though this latter was found to be a piece of silk dating from between 1220 and 1475. There is an 11th-century holy shroud in the cathedral of Cahors, as well as in Mainz and Constantinople, and dozens of other cities claimed to possess fragments of such a relic.[6] An 8th-century sudarium is still venerated in Oviedo, Spain, as if it were authentic.[7]

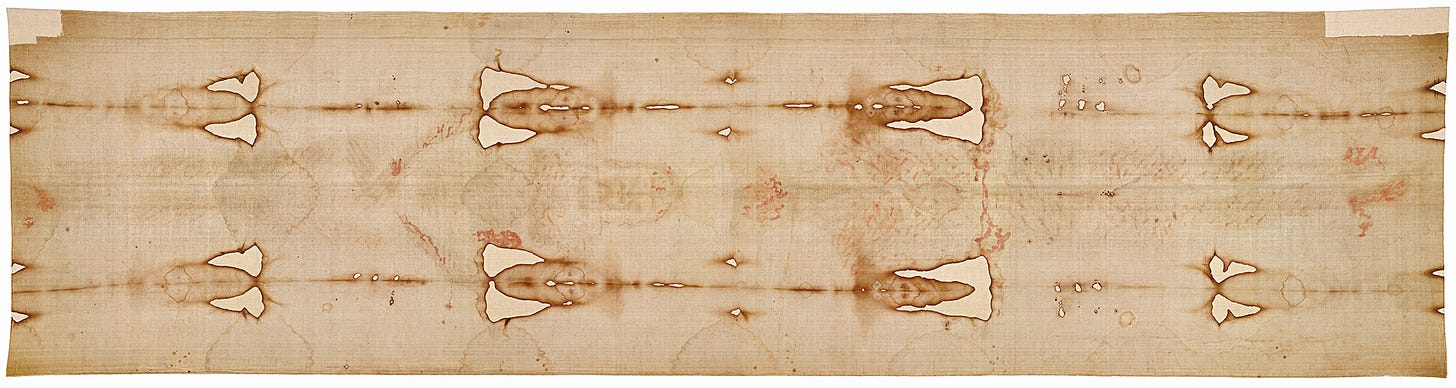

The Shroud of Turin, 14th- 19th Century

With this background it might not surprise readers to learn that the Turin Shroud, in fact, is not one of the oldest but rather one of the most recent such relics. It is a large cloth resembling a long tablecloth over 4 meters in length, featuring a double monochromatic image that shows the front and back of a man. This man bears marks from flagellation and crucifixion, with various red spots corresponding to blows. The Turin Shroud first appeared in the historical record in France (a place that already hosted many competing shrouds) around 1355. It is different from all the previous shrouds in that the others did not display the image of the dead Christ, and until then no source had ever mentioned a shroud bearing such an image (although Rome hosted the well-known Veil of Veronica, a piece of cloth said to feature an image of the Holy Face of Jesus). The explanation behind its creation can be found in the contemporary development of a cult of devotion centered on the representations of the physical suffering of Christ and his wounded body.

The Turin Shroud made its first appearance in a small country church built in Lirey by an aristocratic soldier, Geoffroy de Charny (see figure below). As soon as this relic was put on public display it immediately became the subject of debate. Two local bishops declared the relic to be fake. In 1389, the bishop of Troyes wrote a letter to the Pope denouncing the falsity of the relic and accusing the canons of the Church of Lirey of deliberate fraud. According to the bishop, the canons had commissioned a skilled artist to create the image, acting out of greed and taking advantage of popular gullibility. The Pope responded by making a Solomonic decision, allowing the canons to continue exhibiting the cloth but simultaneously obliging them to publicly declare that it was being displayed as a “figure or representation” of the true Shroud of Christ, not the original.

Pilgrimage badge of Lirey (Aube), between 1355 and 1410. Paris, Musée National du Moyen Âge, CL 4752. (Photo © Jean-Gilles Berizzi / RMN-Grand Palais - Musée de Cluny, Musée Nationale du Moyen-Âge).

Various erasures and acts of subterfuge were required to cover up these historical events and transform an artistic representation into an authentic shroud of Jesus. The process began after 1453, when the relic was illegally purchased by the House of Savoy.

Interpretations of this first part of the history of the Shroud diverge significantly between those who accept the validity of the historical documents and those who reject it. However, the following developments are known and accepted all around. Deposited in the city of Chambéry, capital of the Duchy of Savoy, the Shroud became a dynastic relic, that is, an instrument of political-religious legitimization that shared in the same symbolic language used by other noble European dynasties. After surviving a fire in 1532, the Shroud remained in Chambéry until 1578. It was then transferred to Turin, the duchy’s new capital, where a richly appointed chapel connected to the city’s cathedral was specially built to house it in the 17th century.

Display of the Shroud in the chapel of the Dukes of Savoy; miniature from the Prayer Book donated in 1559 by Cristoforo Duc of Moncalieri to Margaret of Valois. Turin, Royal Library, Varia 84, f. 3v. Courtesy of the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities, Regional Directorate for Cultural and Landscape Heritage of Piedmont.

From that point on, the cloth became the object of a triumphant cult. Historians loyal to the court constructed a false history of the relic’s origins, deliberately disregarding all the medieval events that cast doubt on its authenticity and attested to the intense reluctance of ecclesiastical authorities. In the meantime, the papacy and clergy in general abandoned their former prudence and began to encourage veneration of the Shroud, established a liturgical celebration, and launched theological and exegetical debate about it. The Savoy court, for its part, showed great devotion to its relic and at the same time used it as an instrument of political legitimization,[8] seeking to export the Shroud’s fame outside the duchy by gifting painted copies that were in turn treated as relics-by-contact (there are at least 50 copies known to still exist throughout the world).

Having survived changes of fortune and emerging unscathed from both the rational criticism of the Enlightenment and the Napoleonic period, the Shroud seemed destined to suffer the fate of other similar relics, namely a slow decline. In the meantime, the Italian ruling dynasty had clashed fiercely with ecclesiastical authorities and moved its capital to Rome in the second half of the 19th century; it too began to show less and less interest in the Shroud. Following a solemn exhibition in 1898, however, the Shroud returned to the spotlight and its reputation began to grow outside Italy as well. Indeed, two very important events in the history of the relic took place that year: it was photographed for the first time, and the first historiographical studies of it, carried out using scientific methods, were published.

Shroud Science

Photography made available to everyone what until that moment had been available to only a few: a view of the shape of Christ’s body and the image of his face, scarcely discernible on the cloth but perfectly visible on the photographic plate. It was especially visible in the negative image which, by inverting the tonal values, reducing them to white and black, and accentuating the contrast through photographic techniques, revealed the character of the imprint.

Photographs of the Shroud, accompanied by imprecise technical assessments holding that the photograph proved that the image could not possibly have been artificially generated, were circulated widely. This prompted other scholars to become involved, seeking to explain the origins of the image impressed on the cloth through chemistry, physics, and above all forensic medicine. More recently, these disciplines have been joined by palynology, computer science, biology, and mathematics, all aimed at experimentally demonstrating the authenticity of the relic, or at least removing doubts that it might have been a fake. At the beginning of the 20th century there were many scientific articles published on the Shroud and discussions held in distinguished fora, including the Academy of Sciences in Paris.

Holy Face of the Divine Redeemer, for the exhibition of the Shroud in 1931, photograph by Giuseppe Enrie. (Photo by Andrea Nicolotti).

The scientist associated with the birth of scientific sindonology is the zoologist Paul Vignon, while Ulysse Chevalier was the first to conduct serious historical investigations of the Shroud. Both of these authors were Catholics (and the latter was a priest), but they held completely contrasting positions: the former defended the Shroud’s authenticity while the latter denied it. Canon Chevalier was responsible for publishing the most significant medieval documents on the early history of the Shroud, showing how it had been condemned and declarations of its falseness covered up, and wrote the first essays on the history of the Shroud using a historical-critical method (Chevalier was an illustrious medievalist at the time). The debate became very heated in the historical and theological fields, and almost all the leading journals of history and theology published articles on the Shroud.

After the beginning of the 20th century almost no one applied themselves to thoroughly examining the entirety of the historical records regarding the Shroud (much less compared it to all the other shrouds). After a period of relative lack of interest, new technologies brought the Shroud back into the limelight. In 1978, a group of American scholars, mostly military employees or researchers associated with the Catholic Holy Shroud Guild, formed the STURP (Shroud of Turin Research Project), were allowed to conduct a series of direct scientific studies on the relic. They did not find a universally accepted explanation for the origin of the image. Some members of this group used mass media to disseminate the idea that the image was the result of a supernatural event: in this explanation, the image was not the result of a body coming into contact with the cloth, perhaps involving blood, sweat, and burial oils (as believed in previous centuries) but rather caused by irradiation. At this time the two most popular theories on the historical origin of the Shroud—despite their implausibility—were formulated:

1. The Shroud and the Mandylion of Edessa are one and the same object. The Mandylion is another miraculous relic known to have existed since at least the 6th century BCE in the form of a towel that Jesus purportedly used to wipe his face, miraculously leaving the mark of his features on it;

2. The Knights Templar transported the Shroud from the East to the West, deduced from statements made by the Templars under torture during their famous trial of 1307-1312.

The clash between sindonology and science reached its peak in 1988; without involving STURP but with permission from the archbishop of Turin, the Holy See and the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, a radiocarbon examination was carried out that year involving 12 measurements conducted in three different laboratories. As expected, the test provided a date that corresponds perfectly with the date indicated by the historical documents, namely the 13th-14th century. As often happens when a scientific finding contradicts a religious belief, however, from that moment on attempts to invalidate the carbon dating proliferated on increasingly unbelievable grounds, including: conspiracy, pollution of the samples, unreliability of the examination, enrichment of the radiocarbon percentage due to the secondary effects of the resurrection, etc.

Turin, Palazzo Reale, October 1978: observation of the back of the Shroud during the STURP study campaign. (© 1978 Barrie M. Schwortz Collection, STERA, Inc.)

Dating the Shroud

In 1945 the chemist Willard Libby invented the radiocarbon dating technology Carbon 14 (C14). Despite rumors that Libby was against applying the C14 method to the Shroud, I found proof that at least twice he stated precisely the opposite, declaring his own interest in performing the study himself.[9] In the early-1970s, the test had always been postponed, first because it was not considered sufficiently tested yet, and later because of the amount of cloth that would have to be sacrificed (the procedure is destructive). But by the mid-1980s, C14 was universally considered a fully reliable system of dating, and it was regularly used to date antiques. Several C14 laboratories offered to perform the trial gratis, perhaps imagining that the examination, whatever its result, might bring them much publicity.

Once Cardinal Ballestrero, who was not the relic’s “owner” but only charged with the Shroud’s protection, had made the decision to proceed, he asked for the support and approval of the Holy See. The Pontifical Academy of Sciences was invested with the responsibility to oversee all operations. For the first time in its history, the papal academy was presided over by a scientist who was not a priest, the biophysicist Carlos Chagas Filho. The scientists’ desire was to date the Shroud and nothing more, and they did not want the sindonologists to take part in the procedure (as they had little regard for STURP or other sindonological associations). This desire for autonomy engendered reactions that were, one might say, somewhat vitriolic, since some sindonologists had hoped to manage the radiocarbon dating themselves. The Vatican’s Secretary of State and the representatives of Turin agreed to supply no more than three samples, which were more than enough. Turin chose three of the seven proposed laboratories: those at the University of Arizona in Tucson, the University of Oxford, and Zurich Polytechnic, because they had the most experience in dating small archaeological fragments.

April 21, 1988, was the day chosen for the extraction. The textile experts observed the fabric and discussed the best place to make the withdrawal; after excluding the presence of material that could interfere with the dating, they decided to take a strip from one of the corners, in the same place in which a sample had already been taken for examination in 1973. The strip was divided into pieces and each of the three laboratories received a sample. The procedure was performed under the scrutiny of over 30 people and filmed.

The results were published in the world’s leading multidisciplinary scientific journal, Nature. Conclusion: the cloth of the Shroud can be assigned with a confidence of 95 percent accuracy to a date between AD 1260 and 1390. In response, the Cardinal of Turin issued this statement:

I think that it is not the case that the Church should call these results into question. . . . I do not believe that we, the Church, should trouble ourselves to quibble with highly respected scientists who until this moment have merited only respect, and that it would not be responsible to subject them to censure solely because their results perhaps do not align with the arguments of the heart that one can carry within himself.[10]

Prof. Edward Hall (Oxford), Dr Michael Tite (British Museum) and Dr Robert Hedges (Oxford), announcing on 13 October 1988 in the British Museum, London, that the Shroud of Turin had been radiocarbon dated to 1260-1390.

Predictably, Shroud believers rejected the scientific findings, and started to criticize the Turin officials who had cut the material. The sample of cut-out cloth had been divided into parts, but no one had thought it necessary to write a report with the official description of the subdivisions and the weight of each fragment. There were, however, footage and many photographs, which would have been more than sufficient documentation on a typical occasion.

Others preferred to deny the validity of the method of radiocarbon dating as such. Sindonology had by now assumed the character of pseudoscience, and it is not surprising that it drew not only on the ruminations of the traditionalists but also on the war chest of creationist and fundamentalist literature. The method of radiocarbon dating is in fact used to date objects up to 50,000 years old, which stands in contradiction to the idea of those who believe that the world and the life in it were created only a few thousand years ago. What follows from such creationist convictions is the wholesale rejection of radiocarbon measurements, as well as the rejection of more popular scientific explanations of the origins of the universe, the existence of the dinosaurs, human evolution, and so on. Creationists and fundamentalist Christians had already prepared a whole list of alleged errors in the method of C14 dating, which was promptly copied in the books of sindonology. The alleged errors generally concern cases of objects of a known age that—so they claim—once dated, would yield a result that was off the mark by several hundred or even a thousand years.

But a careful evaluation of these so-called errors (which, however, are always cited in a generic and approximate manner) demonstrates that they do not exist, or that they go back to an earlier epoch in which the dating system had not yet been refined, or that they concern materials that do not lend themselves to radiocarbon dating but whose concentration of carbon 14 is measured for purposes other than those concerned with their age.

Other sindonologists preferred to discredit the C14 result by resorting to the notion of contamination of the samples. This pollution hypothesis claims that through the centuries the Shroud picked up deposits of more recent elements that would, therefore, contain a greater quantity of carbon; the radiocarbon dating, having been performed on a linen so contaminated, would thus have produced an erroneous result. Candidates for the role of pollutants are many: the smoke of the candles, the sweat of the hands that touched and held the fabric, the water used to extinguish the fire of 1532, the smog of the sky of Turin, pollens, oil, and more.

This approach gains traction among those who do not know how C14 dating works; in reality, however, it is untenable. Indeed, if a bit of smoke and sweat were enough to produce a false result, the measurement of carbon 14 would have already been declared useless and one could not understand why it is still used today to date thousands of archaeological and historical finds each year. The truth is rather that the system is not significantly sensitive to such pollutants.

Let us suppose that we were to admit that the fabric of the Shroud dates back to the 30s of the first century; we also admit that the Shroud has suffered exposure to strong pollution, for example, around 1532, the year of the Chambéry fire. To distort the C14 dating by up to 1,300 years, it would be necessary that for every 100 carbon atoms originally present in the cloth, another 500 dating to 1532 be added by contamination. In practice, in the Shroud, the amount of pollutant should be several times higher than the amount of the original linen, which is nonsense. Things get even worse if we assume that pollution did not happen all at the same time in the 16th century, but gradually over the previous centuries. In this case there is no mathematical possibility that pollution having occurred before the 14th century—even if tens of times higher than the quantity of the original material—could give a result of dating to the 14th century. It should be added, moreover, that all samples, before being radiocarbon dated, are subjected to energetic cleaning treatments able to remove the upper patina that has been in contact with outside contaminants; this procedure was also undertaken on the Shroud.

Those who believe that the Shroud was an object that could not be dated because it was subjected to numerous vicissitudes during the centuries evidently do not know that often C14 dating laboratories work on materials in much worse condition, whether coming from archaeological excavations or from places where they have been in contact with various contaminants. For a radiocarbon scientist, the Shroud is a very clean object.

A more curious variant of the pollution theory suggests that the radiocarbon dating was performed on a sample that was repaired with more recent threads. This would force us to imagine that two widely recognized textile experts who were present on the day of the sampling were unable to notice that they had cut a piece so repaired, despite the fact that they had observed the fabric carefully for hours; to distort the result by 13 centuries the threads employed in the mending would have had to have been more numerous than the threads of the part to be mended. To eliminate any doubt, in 2010 the University of Arizona reexamined a trace of fabric leftover from the radiocarbon dating in 1988, concluding:

We find no evidence for any coatings or dyeing of the linen. . . . Our sample was taken from the main part of the shroud. There is no evidence to the contrary. We find no evidence to support the contention that the 14C samples actually used for measurements are dyed, treated, or otherwise manipulated. Hence, we find no reason to dispute the original 14C measurements.[11]

Among the various attempts to invalidate the radiocarbon procedure, there is also one based on an examination of the statistical analysis of the laboratories that carried out the C14 tests. In general, it is interesting to note that, as Dominican Father Jean-Michel Maldamé wrote, “the disputes over the carbon 14 dating do not come from individuals who are competent in the subject of dating.”[12] Rather, a publication concerned with the use of radiocarbon in archaeology dedicates an entire chapter to the dating of the Shroud and to the various criticisms put forth by sindonologists to discredit it. The conclusion states:

For those whose interest in the Shroud is dominated by a belief in its religious or devotional function, it is virtually certain that any scientifically based evidence, including any additional 14C-based data, would not be compelling—unless, of course, it confirmed their beliefs.[13]

The final possibility raised against C14 dating falls within the sphere of the supernatural. As the radiocarbon present in the Shroud is excessive relative to the hopes of sindonologists, at the 1990 sindonology convention a German chemist, Eberhard Lindner, explained that the resurrection of Christ caused an emission of neutrons that enriched the Shroud with radioactive isotope C14.[14]

Miraculous explanations can be constructed with such scientific jargon but they have no chance of being scientifically tested (as there is no availability of bodies that have come to life from the dead and emit protons or neutrons). They are, however, extremely convenient because they are able to solve any problem without having to submit to the laws of nature.

With all of the available evidence it is rational to conclude—as the most astute historians had already established more than a century ago—that the Shroud of Turin is a 14th century relic and not the burial cloth of a man executed by crucifixion in the 1st century. Only the historiographical study of this object, accompanied by the scientific and critical examination of sindonological claims past and present, can provide us with a clearer picture of this relic’s real background.

References

[1] Nicolotti, Andrea. 2011. I Templari e la Sindone. Storia di un falso. Rome: Salerno editrice.

[2] Nicolotti, Andrea. 2014. From the Mandylion of Edessa to the Shroud of Turin: The Metamorphosis and Manipulation of a Legend. Leiden and Boston: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004278523

[3] Nicolotti, Andrea. 2018. “La Sindone di Torino in quanto tessuto: analisi storica, tecnica, comparativa.” In Non solum circulatorum ludo similia. Miscellanea di studi sul Cristianesimo del primo millennio, ed. Valerio Polidori, 148-204. S.l.: Amazon KDP.

[4] Nicolotti, Andrea. 2019 [2015]. The Shroud of Turin. The History and Legends of the World’s Most Famous Relic. Transl. Jeffrey M. Hunt and R. A. Smith. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press. Originally published as Sindone. Storia e leggende di una reliquia controversa. Turin: Einaudi.

[5] Pomian, Krzysztof. 1990 [1987]. Collectors and curiosities. Paris and Venice, 1500-1800. Transl. Elizabeth Wiles-Portier. Cambridge: Polity Press. Originally published as Collectionneurs, amateurs et curieux. Paris, Venise: XVIe - XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Gallimard, 30.

[6] Ciccone, Gaetano, and Lina Sturmann. 2006. La sindone svelata e i quaranta sudari. Livorno: Donnino.

[7] Nicolotti, Andrea. 2016. “El Sudario de Oviedo: historia antigua y moderna.” Territorio, sociedad y poder 11: 89-111. https://doi.org/10.17811/tsp.11.2016.89-111

[8] Nicolotti, Andrea. 2017. “I Savoia e la Sindone di Cristo: aspetti politici e propagandistici.” In Cristo e il potere. Teologia, antropologia e politica, ed. Laura Andreani and Agostino Paravicini Bagliani, 247-281. Florence, SISMEL - Edizioni del Galluzzo; Cozzo, Paolo, Andrea Merlotti and Andrea Nicolotti (eds). 2019. The Shroud at Court: History, Usages, Places and Images of a Dynastic Relic. Leiden and Boston: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004390508

[9] The judgment is cited by Wilcox, Robert. 1978. Shroud, 147-48. London: Corgi Book. According to Pierluigi Baima Bollone, Libby asked for a piece of cloth from the Shroud in order to date it (P. Baima Bollone, “Perché la Sindone non è stata datata con il radiocarbonio?,” Stampa sera, September 17, 1979, 5).

[10] Conference on October 13, 1988 (audio transcription).

[11] R.A. Freer-Watersand, A.J.T. Jull, “Investigating a Dated Piece of the Shroud of Turin,” Radiocarbon 52, no. 4 (2010): 1526.

[12] J.-M. Maldamé, “À propos du Linceul de Turin,” Connaître: Revue éditée par l’Association Foi et Culture Scientifique 11 (1999): 64.

[13] R.E. Taylorand, O.Bar-Yosef, Radiocarbon Dating: An Archaeological Perspective, 2nd ed. (Walnut Creek: Left Coast, 2014), 169.

[14] The idea had already occurred to T. Phillips, “Shroud Irradiated with Neutrons?,” Nature 337 (1989): 594.

I have a different question about the psychology of human belief: why are most people deliberately selective about how and when they embrace belief as valid, and when they at least claim to support rational objectivity, aka "science", over belief?

To provide a deliberately provocative example, why do so many American liberals dismiss Christian theology, including relics like the shroud, and its utility as a foundation for morality and politics, but then embrace Native American religion and all their associated totems, and eagerly create laws and policies in accordance with those animist beliefs? Is this an expression of more fundamental human desire for political advantage, or just an expression of typically irrational and inconsistent human psychology?

The sample was not from the main part of the cloth it was taken from a repaired part of the shroud there’s photographic evidence to it. So you have a whole article stating the shroud is from the 14th century and therefore is not the burial cloth of Jesus and you sight ONE piece of evidence for it being a fraud? How about the fact that no one can come up with an explanation on how the image was formed? The best anyone has come to explain it was the use of some 1400 lasers being set off at the same time in a split second? I’m not a scientist but I would think that might be a hard thing to do in the 1300’s(note the sarcasm)…how about the fact that the blood(yes it’s real blood) seaps through to the back of the cloth yet the image is only a few hairs deep? Meaning that the blood was there first then the image after…why would a forger go through all that trouble? Why is there blood on the wrist and not on the hands? All images of Christ show the nails through the hands in paintings in that era…why and how would a forger know to put the nails through the wrists? How about the new evidence to the date of the shroud that just came out in 2024 dating it back to the first century? It’s truly amazing that on one side you have all this evidence to its authenticity being about 10 feet high and on the side of it being a fake you have one piece of evidence that’s about a centimeter high.